News & Views

Reflections: Beside Still Waters

James Harpur contemplates St Columba, Covid and the Rainmaker

St Columba and his monks sailing in a coracle. Columba had the reputation of being able to change the direction of the wind through the power of prayer. Image from Historic Environment Scotland

‘The wild donkeys stand on the bare heights; they pant for air like jackals; their eyes fail because there is no vegetation.’ Jeremiah (14: 5–6)

Shortly before his death in the summer of 2020, the British educationalist and thinker Sir Ken Robinson proposed in his last public talk, entitled ‘Creating a New Normal’, that the Covid pandemic ‘was largely of our own making’, adding that ‘humanity … has created all kinds of conditions that are hostile to our best interests’.[1] He mentioned, for example, our neglect of nature and how farming methods prioritise monocultures over diversity in the interests of high yields. He also likened this practice to school education, in which the ‘one-size-fits-all’ model puts students through the monoculture of the exams system rather than cater for the diversity of individual talents. The combination of industrial farming and rigid education and many other factors, including CO2 emissions, has, he maintained, contributed to hostile living conditions. Without actually spelling it out, Robinson implied that the Covid-19 virus has been allowed to take a grip and thrive because of our modern Western work methods and lifestyle.

If Robinson is correct, how do we make our living conditions less hostile? After all, it would be naïve to think that after Covid another microscopic hydra-headed virus will never rear its head again. What can we do to prepare for such an eventuality? On reflecting upon this conundrum I was struck by how different our current Western response to Covid has been compared to the various instances of crisis management found in the Life of St Columba, written by Adomnán (d.704).[2] In this work, Columba / Columkille frequently has a calming, curative or healing effect not only on those close to him on Iona and elsewhere, but also on the natural world and phenomena such as storms.

This in turn reminded me of a story about a Chinese Daoist ‘rainmaker’ that Carl Jung believed held valuable spiritual and practical lessons. Jung had heard the story from his German friend Richard Wilhelm, a Chinese scholar, who witnessed the events described in the story in the 1920s.[3] Could the example of Columba and the story of the rainmaker hold any lessons for us?

Tai Shan Confucian Monastery in Shandong Province, the region where Richard Wilhelm lived in China. Photograph: Karl Johaentges [/] /Alamy Stock Photo

The Story of the Rainmaker

.

The rainmaker story revolves around a terrible drought that struck the area of China where Wilhelm was living. The situation was critical, especially after a series of various folk rituals and prayers uttered by local Christians had proved ineffective. In desperation the local people sent for a Daoist ‘rainmaker’ from another province. This elderly man duly arrived and simply asked for a small quiet house to isolate himself in. There he remained for three days, during which time nothing apparently happened. No rain appeared and the locals wondered what on earth he was doing – if anything. But on the fourth day clouds suddenly gathered and a storm of snow – almost unheard of at this time of the year – materialised and soaked the land.

When Wilhelm himself asked the rainmaker how he had achieved this apparent miracle, the latter replied: ‘Actually I didn’t create the snow. I’m not responsible for that.’ He went on to explain that the region he had just come from was a place of harmony where things were in order. However, here, in this drought region, things were disharmonious and out of kilter with ‘Dao’, the ‘right order of nature’. The rainmaker said that because the area was ‘not in Dao’, this had meant that he, too, was not in Dao – the disorder he felt to be all around him in the atmosphere had made him disordered too. To remedy this he had decided to wait in isolation for three days to allow himself to return to harmony with Dao. And when that happened, the snow came naturally.

The story has all sorts of implications, but the basic thrust seems to be that being in harmony with oneself has a tangible effect on one’s immediate environment. The story hinges upon the Chinese notion of Dao, which literally means ‘way’, but refers, among other things, to what might be called the ‘cosmic principle of order’. Dao is unlike the Christian God in that, for example, it is not a personal entity or held to have created the universe. It is more akin to the ordering principle behind nature (perhaps closer to the Christian idea of ‘logos’) as well as the flow of energy that makes things flourish and find the form or way that is right for them. An oak tree that is ‘in Dao’ would be one that has grown into a magnificent shape conforming to its innate and typical form. A person being in Dao would suggest that he or she has found the right path for his or her life and is finding fulfilment as a result. Jung’s comment on the story was that: ‘If one has the right attitude, then the right things happen. One doesn’t make it right, it is just right, and one feels it has to happen in this way.’[4]

Although Dao is not the equivalent of the Christian or the Jewish God, there are places in the Bible when God is said to confer a personal inner stillness that brings about a healing effect reminiscent of ‘being in Dao’. Psalm 23, for example, says that God ‘leads me beside still waters. He restores my soul.’ Psalm 46:10 enjoins us to ‘be still and know that I am God.’ Conversely, Jeremiah (14: 5–6) describes how the ‘iniquities’ of God’s people were directly responsible for bringing about a drought in which the ‘wild donkeys stand on the bare heights [and] pant for air like jackals…’. The Book of Amos also links drought with human errancy: ‘I [the Lord] also withheld the rain from you … yet you did not return to me.’ In a similar vein, 2 Chronicles (7:13–14), says: ‘… if my people … turn from their wicked ways, then I will … forgive their sin and heal their land [my italics].’ A person’s ordered living and inner harmony affects the outer world, and humility is the key: reliance on self prevents the connection with the divine ordering of nature, and this prevents the rain from coming and ‘healing’ the earth.

Iona Abbey, on the island of Iona off the West coast of Scotland, founded by St Columba. Photograph: Alan Morris/iStock

The Example of St Columba

.

In the Life of Columba the saint’s inner harmony often has a beneficent effect on those around him, as well as on nature. It is as if he, like the rainmaker, was able to tune or re-tune himself to the divine source of life (becoming ‘in Dao’, as it were) and change something for the better. On one occasion he and his monks were sailing on the sea when they were struck by a great storm. The boat was shipping water and the sailors were frantically bailing it out, with Columba joining in their efforts. Suddenly the sailors told him it would be much better if he just prayed for them instead. Columba stopped bailing the ‘bitter waters back into the green sea’ and began to pour out ‘a sweet and fervent prayer’ to God, and almost immediately the storm died down and a perfect calm ensued.[5]

As with the rainmaker, the solution to the natural disaster lay not in physical effort but in ‘doing nothing’ or, in Columba’s case, praying; and prayer itself, like meditation or ‘waiting’, is a way of tuning into and effecting ‘at-one-ment’ or harmony with the divine. The temptation for Columba was to help the sailors physically. But their plea brought him to his senses, and, in Daoist terms, when he found inner harmony through prayer, the storm naturally abated.

Adomnán also tells a story about a visitor to Iona who was clearly not in Dao; Adomnán describes him as being non subtilis sensus – ‘lacking in finer feelings’, that is, crass or blundering. The visitor, evidently well-meaning, barges in to greet Columba in his scriptorium and spills ink from an inkhorn. It is a seemingly trivial incident but a clear example of how innate inner turmoil affects outer circumstances. A Jungian might suggest that the incident was not an ‘accident’ but the natural result of a turbulent nature.[6]

There are other stories in Adomnán’s Life of St Columba that echo the idea of ‘being in Dao’ and that an inner harmony affects a location. One in Book 2 occurred when Adomnán was abbot of Iona, about a century after Columba’s death, and involves a drought, thus making an interesting direct comparison with the rainmaker story.[7] One springtime, alarmed by a critical lack of water, Adomnán and his brethren resorted to a set of sacred rituals to make the rain come. These included reading aloud from books written in Columba’s own hand at a local hill where the saint was once said to have communed with angels. Soon after the recitation the skies filled with cloud and rain poured down, softening the parched earth and bringing forth a good harvest.

Adomnán’s account differs from the rainmaker story in that the monks performed rituals rather than simply remaining in their cells and waiting, as the rainmaker did. But perhaps what they did was the nearest Christian equivalent of ‘returning to Dao’: reading Columba’s books on a hill believed to be a threshold between earth and heaven could be interpreted as a successful attempt to reestablish an inner spiritual equilibrium. In Daoist terms the monks created orderliness within themselves and thereby put back into balance the order of nature; after that, the rain came naturally. In Christian terms the monks might have been mindful of Leviticus 26:3–4: ‘If you walk in my statutes and observe my commandments and do them, then I will give you your rains in their season.’ The rainmaker and the monks were essentially doing the same thing: restoring inner harmony and thereby facilitating the harmony of their external worlds.

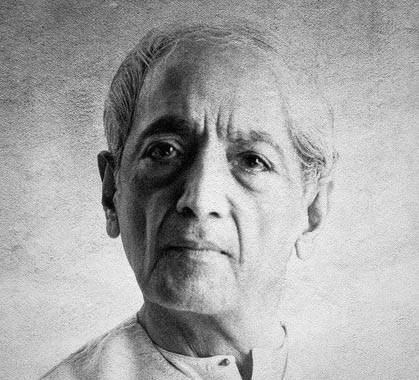

The Indian-born writer and teacher Jiddu Krishnamurti

Being ‘in Dao’ today

.

Walking in God’s statutes and observing his commandments, or being in Dao, are not ideas or practices now favoured in Western, mainly secular, societies. The prevalent humanism, rationalism and scientific advances have eroded age-old religious, metaphysical and spiritual beliefs and practices (and it must be said, brought great benefits in their wake: we no longer burn witches or fear influenza as we once did). However the power – thrall even – of machines, devices and microchips has removed us farther from nature and done nothing to stop the idea that the earth is a resource to be exploited rather than a living, organic ecosystem to be tampered with at our peril. Droughts, floods and hurricanes are now routinely connected with human practices on earth. Our responses have largely centred on large-scale conferences, at which a cynic might observe that the hot air emitted by the candidates has done more to worsen global warming than any positive actions prompted by their words.

Yet can the stories of the rainmaker and Columba have any relevance for us and our struggles with environmental problems and Covid? I believe that they can, and might possibly be the only long-term approach to our current challenges. In terms of the virus, Adomnán actually mentions a plague that twice affected Britain and Ireland during his lifetime – a pestilence that ravaged these two countries except among ‘the Picts and Scots [Irish] of Britain’.[8] For Adomnán the saving grace for these peoples was the presence of Columban monasteries within their territories, as if their holy atmosphere had created a force-field of protection.

It is hard for us to countenance the idea of a Columban or indeed any other type of monastery having an exclusively positive effect on its surroundings during the plague then, or indeed the Covid pandemic now. (It should be noted, however, that the rhythm of monastic life, with its natural self-isolation, outdoor physical work, unpolluted air, fresh organic food and regular periods of prayer and meditation, would surely boost the immune system more than ‘couch-potato-ism’, screen addiction and processed foods.) One among many modern ripostes to Adomnán’s advocacy of Columban spirituality might be that we have the vaccines that Columba lacked. Yet it might be too soon to say whether mass vaccination is a long-term solution, or even a short-term one: the Covid-19 virus has a life and an intelligence of its own and seems to be engaged in a cosmic board game with our most able scientists. The situation is reminiscent of the opening scene from Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal, set in a plague-ridden land, in which the knight plays chess with Death, believing he will live as long as the game continues.

The Chess Game in Ingmar Bergman’s 1957 film The Seventh Seal

Vaccines are currently our best defence against Covid. But the rainmaker story and Columba point towards another way to help to combat viruses in order to save the planet. It is essentially the same way that the Indian-born spiritual speaker Jiddu Krishnamurti (1895–1986) used to emphasise in his many talks over sixty years: the root of all positive change lies in the individual becoming at one with him- or herself through meditation, stillness, waiting, prayer. These are different terms that describe allowing the ego or self to subside, and letting the resultant stillness and silence induce inner harmony and a greater beneficent force or energy (which the Chinese would call ‘chi’, as in tai chi, or Christians the holy spirit).

Krishnamurti himself talked about the value of being ‘choicelessly aware’, a sort of meditative state of ‘passive alertness’ that allow us to be more sensitive to our surroundings and develop empathy with them, whether they are people or objects. His point is that if we look at a bird or tree, say, and our heads are spinning with choices, thoughts, plans, anxieties and so on, no relationship with the bird or tree can take place. But if we are still and alert, letting the internal chattering subside, it is possible to make a deeply felt connection with the world:

Be in communion with nature, not verbally caught in the description of it, but be a part of it, be aware, feel that you belong to all that, be able to have love for all that, to admire a deer, the lizard on the wall, that broken branch lying on the ground.[9]

Krishnamurti was instinctively suspicious of organised groups and movements, no matter how noble the cause they espoused, and believed that it was only through individuals changing themselves from the inside that big issues, such as pollution and climate change, could be tackled. He also believed that a person’s felt kinship with nature made him or her feel empathetic towards other people. If we are sensitive towards the smallest thing – an ant or a fly – that feeling of empathy can lead us to:

… a sense that we are all together, that we are all human beings, not divided, not broken up, not belonging to any group or race or some idealistic concepts, but that we are all human beings, living on this extraordinary, beautiful earth.[10]

The emphasis of Krishnamurti, Columba and the rainmaker is on forming a right relationship with ourselves, thereby tuning into a greater energy, or God, or Dao. Harmony starts at home, and reliance on others – politicians, scientists, priests – and big conferences and big protest marches is a way of abrogating responsibility. The state of our inner being naturally affects the lives of others as well as nature. As William Blake said: ‘As a man is, so he sees … To the eyes of a miser, a guinea is far more beautiful than the Sun.’ Self-harmony is difficult and arduous: waiting, praying, or letting ‘choiceless awareness’ emerge is much harder to achieve than dealing in moral outrage, action groups and twitter storms, because it requires humility and patience and ‘inaction’. Krishnamurti puts it well:

To be in communion with yourself means complete silence so that the mind can be silently in communion with itself about everything. And from there, there is total action. It is only out of emptiness [i.e. a mind that is free of the ego and its restless, chattering voice] that there is an action that is total and creative.[11]

In achieving an inner communion or harmony we may also help to bring about an outer harmony and make our natural environment hostile not to ourselves, but to viruses.

James Harpur has published eight books of poetry and is a member of Aosdána, the Irish academy of arts. His latest books are The Oratory of Light (Wild Goose Publications, 2021), poems inspired by St Columba and the island of Iona; and his debut novel, The Pathless Country (Cinnamon Press, 2021), in which J. Krishnamurti appears as a character. For his website, click here

To read James’ previously article for Beshara Magazine – on the Book of Kells and the way in which it inspired his poetry – click here.

More News & Views

Don’t Take It Easy

Richard Gault is inspired by Michael Easter’s book The Comfort Crisis and explores the idea of ‘misogi’ during a 600-mile walk across Scotland

Book Review: ‘The Serviceberry’

Martha Cass contemplates the message of a new book by Robin Wall Kimmerer that advocates ‘an economy of gifts and abundance’

Book Review: ‘Conversations with Dostoevsky’

Andrew Watson engages with an innovative new book by George Pattison which explores Dostoevsky’s relevance in the contemporary world

Thich Nhat Hanh & the Poetry of Engaged Buddhism

Philip Brown presents the poem ‘Recommendation’ and comments on the potential of contemplative art to foster compassion

Introducing… ‘Perfect Days’ and ‘Nowhere Special’

Jane Clark watches two films with a contemplative theme

Book Review: ‘Irreducible: Consciousness, Life, Computers and Human Nature’

Richard Gault reviews a new book by Federico Faggin, one of the leading lights of the science of consciousness

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

Sources (click to open)

[1] Sir KEN ROBINSON, Creating a New Normal. To watch the video, click here [/].

[2] See ADOMNÁN OF IONA, Life of St Columba, translated by Richard Sharpe (Penguin Books, 1995).

[3] C.G. Jung, ‘Mysterium Coniunctionis: an Inquiry into the Separation and Synthesis of Psychic Opposites in Alchemy’, in vol. 14 Bollingen Series XX: The Collected Works of C. G. Jung, 2nd edition, trans. by R.F.C. Hull (Princeton University Press, 1976), pp.419–20.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Life of St Columba, Book 2, p.12.

[6] Ibid. Book 1, p.24.

[7] Ibid. Book 2, p.44.

[8] Ibid. Book 2, p.46.

[9] J. KRISHNAMURTI, The Whole Movement of Life is Learning (Craft-Verlag, 2015), Chapter 54.

[10] Ibid.

[11] J. KRISHNAMURTI, On Nature and the Environment, see webpage [/].

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READERS’ COMMENTS

2 Comments

Submit a Comment

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

A Sufi saying “Breathe through everything”

Thank you for publishing good and inspiring and alive articles, holding on to a thread.