News & Views

Metaphysical Animals: How Four Women Brought Philosophy Back to Life

by Clare Mac Cumhaill and Rachael Wiseman

Keith Hammond reviews a book about the experience of four remarkable women in wartime Oxford

The Dining Hall in Somerville College during the war years, when Mary Midgley, Iris Murdoch and Philippa Foot were students there. Photograph: Courtesy of the Principal and Fellows of Somerville College, Oxford

This book is about Iris Murdoch [/], Mary Midgley (nee Stratton), Philippa Foot [/] (nee Bosanquet) and Elizabeth Anscombe [/], who were all undergraduates at the same time in Oxford during the Second World War. After their studies, all four went on to have a major influence on philosophical thought in the second half of the twentieth century. Although this book is not about their later impact, it does propose that their Oxford years were in some way a determinant of their subsequent success. As undergraduates, they demonstrated that they had fierce intellects which they exercised in their own way. What is really fascinating in this study, however, is the account of the incredible friendship they established in these early years, which lasted for the whole of their lives.

The world these women entered in 1938 was one dominated by Logical Positivism [/] as expounded by A.J. Ayer’s book, Truth, Language and Logic, published in 1936.[1] This claimed that the only meaningful philosophical problems are those that can be solved through empirical analysis, aiming to replace traditional problems of metaphysics. Empirical problems, of course, have the advantage that they can be solved by empirical observation, placing philosophy on a par with the physical sciences. What is impressive about these women is that they were never sold on Positivism; they were each convinced that metaphysics could not be swept aside in philosophy without the whole discipline being in some way harmed. At a time when the world was grappling with the evil of the Nazis and the barbaric fall-out from Hiroshima, they maintained a line of enquiry on values and the fundamental nature of goodness, asking questions such as: what is the nature of humans? and: what constitutes a just war?

In their later years, the women would come to be associated with what is called ‘virtue ethics’ [/]. But this was never a term they themselves used to describe their work. Philippa Foot’s work, it is true, was clearly in that vein, but not the work of her three companions. An ethics based on character was a more common theme. This led directly into Iris Murdoch’s work in literature, where all the characters in her many novels are interesting from the philosophical point of view. Mary Midgley focused her later work on environmental ethics and animal rights. She did not publish anything until she retired from lecturing at the University of Newcastle. She wrote her first book, Beast and Man in 1978,[2] when she was in her late fifties, and went on to write over 15 more. She became known particularly in her later years for the fierce debate she carried on with the Oxford-based biologist Richard Dawkin, a committed neo-Darwinist.

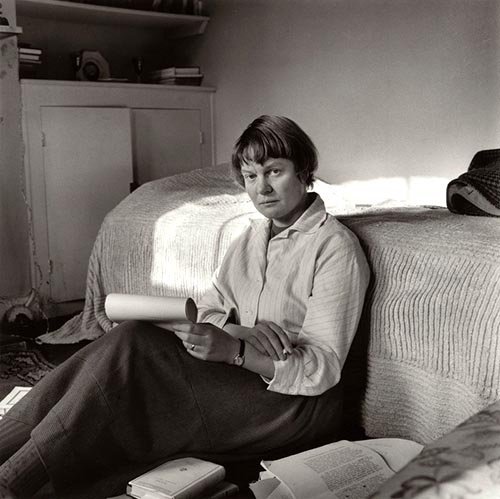

Iris Murdoch (1919–99) in 1957, by which time she had already published three of the 26 novels that made her a household name. She also produced some significant philosophical works on moral philosophy. In 1987 she was made a Dame of the Order of the British Empire. Photograph: Ida Kore/National Portrait Gallery

The War Years in Oxford.

Seven chapters constitute the body of the book, which covers the war years and the period up to 1956. It begins with Midgley’s experience in Vienna in 1938 just before going up to Oxford. She watched the Nazis march into Vienna with broken glass underfoot whilst she was on a visit with her friend Jean Rowntree (of the famous Rowntree philanthropist family), staying with a Jewish family whom her parents subsequently helped acquire the right papers for fleeing Vienna and travelling to the UK. She watched ‘Peace in Our Time’ fade away as the swastika flags went up everywhere and Hitler annexed Czechoslovakia, then moved into Poland.

These images stayed with Midgley as she returned to England and went up to Oxford, which she found also to be in the grip of war. Important scholars were being recruited into the war effort and promising young men were packing up their things and leaving to take up commissions. Amidst all this activity, she found Iris Murdoch, who was also joining Somerville College to read Classics (known as Greats in Oxford). They found that they were the only two women in that year studying this course.

The descriptions of Oxford in the early chapters are beautifully fluid. They read like someone being given a tour on the back of a bicycle, providing endless geographical detail: who lived where and taught what in which college. Only halfway through the book does the narrative switch to places like Cambridge and London, as the women graduated and spread their wings to find jobs in Whitehall ministries. Further into the book we read of Murdoch working for the United Nations Relief Agency in Belgium where she read, and was overwhelmed by, the work of Sartre. Anscombe moved to Cambridge after graduation and came across Wittgenstein [/]. Their encounter was hugely significant, and can be said to have framed almost everything in modern philosophy ever since.

Oxford, however, is where most of the narrative takes place, in the grad-grind of ordinary undergraduate life that has shaped one generation after the next of important figures in the arts and sciences. Surprisingly, in an institution known around the world for continuity and tradition, the picture given of it during the war is one of incredible change. Gaps left by men like Ayer and his circle as they left the university to join the war effort were filled by women and refugee philosophers and lecturers from all over Europe. The presence of these new professors with romantic-sounding names, along with female academics, had an enormous impact on the university. Women were new to higher learning and the academics from Europe unfamiliar with the ways of Oxbridge learning. New practices emerged almost overnight. For instance, seminars and reading groups were not the norm until 1939.

The list of names teaching philosophy in the Martinmas term of 1939 is staggering: Richard Walzer on ‘Platonism in Islamic Studies’, Henry Cassirer on ‘Kant and moral philosophy’ and Palnello on mediaeval philosophy appear alongside British female scholars like Mary Glover – who introduced Anscombe to Plato – and the Scottish conscientious objector, Donald MacKinnon, who first coined the term ‘metaphysical animals’ in a description of Iris Murdoch and her friends, explaining:

A human being is an animal, and its nature – its essence – is expressed in its curiosity and imagination. Human animals speak and ask questions about goodness, meaning and truth. Deprive [them] of the capacity and opportunity to ask metaphysical questions, as totalitarianism does, and what is left? Cynicism, scepticism and fear…. Metaphysical animals need to speak about the transcendent, about the human spirit and the infinite (p. 91).

Equally staggering was the behaviour of various scholars in some of the classes. Cumhaill and Wiseman describe how, at Cambridge, Wittgenstein’s silences would become famous – or infamous – as indeed would the hour-long silences and mumblings of Elizabeth Anscombe in her tutorials, surrounded by groups of confused young students. Strange behaviour was accepted and even seen as standard for much of the time. Even so, one incident recorded by the authors when Anscombe was arranging for Wittgenstein to give a paper in Cambridge stands out:

It was almost a year to the day since the [Cambridge Moral Sciences] club had witnessed the famous incident when Wittgenstein had threatened Karl Popper with a poker. (p. 188)

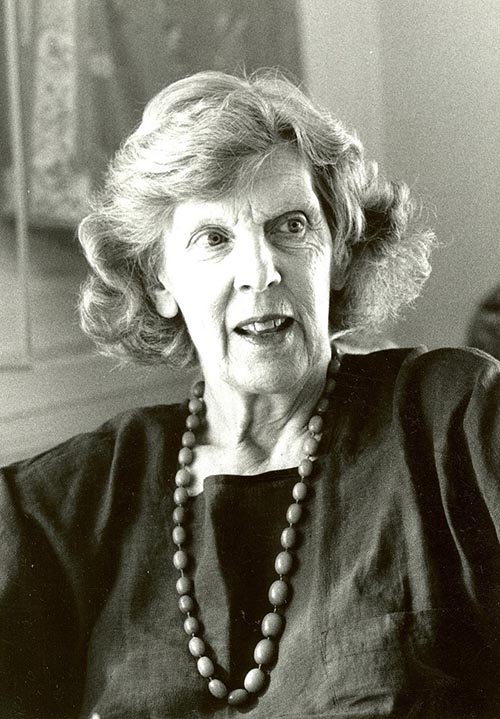

Philippa Foot (1920–2010) in 1979 at Somerville College, where she remained after graduation to become first a lecturer in philosophy and finally a Senior Research Fellow. She is regarded as one of the founders of contemporary virtue ethics, being inspired particularly by the works of Aristotle. Photograph: Courtesy of the Principal and Fellows of Somerville College, Oxford

A Sense of Purpose

.

We are given images of bright young things dashing around Oxford on bicycles with black gowns blowing in the wind like Jean Brodie on Edinburgh High Street that no doubt concealed fierce ambition. Yet the valorisation of friendship in the competitive conditions of academia comes to the fore constantly in this book. The sense of solidarity between these four women, formed early in their undergraduate life, strengthens as the narrative of the book progresses, although this is not without some extremely testing episodes involving male partners and lovers. The mess that is life is never out of the frame. Yet the feelings of these four women for one another give their story a unique quality that is mirrored in their collective relationship and commitment to philosophy.

There is no doubt that they suffered heart-aches, as did everyone else who lived through the Second World War. Murdoch’s fiancé Frank Thompson was dropped into occupied Bulgaria as a member of Special Operations and was captured, tortured and executed by the Nazis in June 1943. Before leaving Oxford he penned the following:

So we, whose life was all before us,

Our hearts with sunlight filled,

Left in the hills our books and flowers,

Descended, and were killed.

Anscombe’s brother John was killed in India and Midgley’s friend Nick Cosby went down earlier in the war with his ship, HMS Goshawk. But through moments of personal loss the women maintained a clear sense of philosophical purpose which Cumhaill and Wiseman describe carefully, so that what ultimately shines through is a shared feeling of wonder and puzzlement which fired their work. It was as though this love of real enquiry created a deep pact between themselves and philosophy that kept them going. Without this commitment and support from friends, Elizabeth Anscombe would not have been able to look after the dying Wittgenstein whilst pregnant with her third child and struggling to keep up teaching loads and research tasks in both Cambridge and Oxford.

I would concur with the central thesis of the book that Anscombe, Foot, Murdoch and Midgley changed philosophical discourse in the UK. This without doubt came out of ‘what’ they reasoned as much as ‘how’ they structured their reasoning. But how they came to make choices about their different philosophical directions during these early years is not explained. Individually and collectively, we read, they showed a clear indifference to positivist perspectives that marginalised metaphysics, but we do not find out why they were able to turn against it with such resolute confidence when much of Oxford was enthralled by Ayer’s theory. For young undergraduates to have been so confident about their own position seems remarkable. Where did that confidence come from? Good arguments, they thought, were not enough. Good choices had also to be made at the right moments. How did these women support and inform one another in making those choices? Together they seemed to have picked up on the pulse of philosophy and nurtured the spirit of the subject by addressing problems that had to be faced but were not being tackled at that time. They each pursued different approaches which were not without opposition from some extremely formidable quarters. Yet they weathered this even as relatively young philosophers. That their confidence related to their friendship is made clear by the authors of this book, but the reader is left asking for more details.

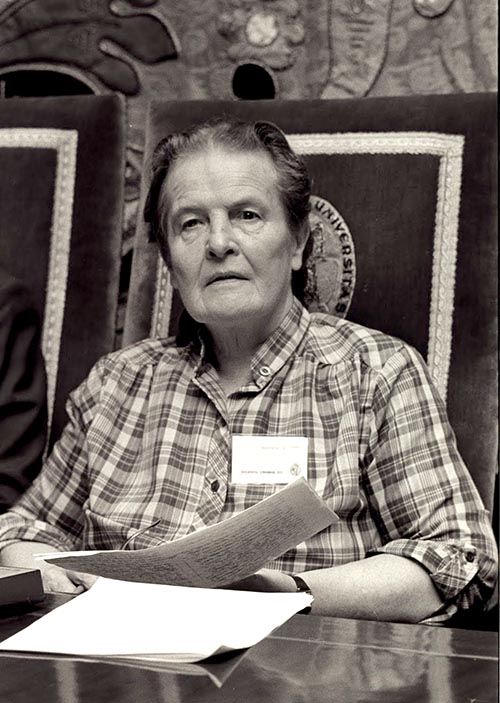

Elizabeth Anscombe (1919–2001), date and place unknown. After graduation, she studied at Cambridge, where she became associated with Ludwig Wittgenstein, editing and translating many books drawn from his writings as well as making significant contributions to the field of analytic philosophy in her own right. She went on to become Professor of Philosophy at Cambridge and a Fellow at Somerville College Oxford

A Common Aim?

.

The other question that remains open is whether, over and above their friendship and shared love of philosophy, the four women were aware of a common aim. Cumhaill and Wiseman say that they were, maintaining that much of their shared interest came from an opposition to the way Oxford philosophy was moving. But this is a point that can be argued. What can be said is that all four of them had some incredible tutors, like Wittgenstein and Donald MacKinnon, who never had much time for analytic enthusiasm of the positivist kind. As a result they were encouraged to explore connections in their work that other philosophical perspectives did not even see. Emptying philosophy of any metaphysical complexities, they argued, deadened the discipline. They thus took up awkward connections between war and morality, vision and what was conducive to living a good life.

The book details one episode in 1946 when Elizabeth Anscombe opposed a proposition by the University to give an honorary degree to the President of the United States, Harry Truman. Gowned figures of eminent Oxford men mobilised in numbers on hearing that ‘the women were up to something’, crowding into the Convocation House for a debate about whether or not Truman should be so honoured. The general mood was overwhelmingly to go ahead with the honour but events did not follow the mood as smoothly as planned, thanks to Anscombe. She sat at the back of the hall and listened carefully as the discussion got under way. Then she got to her feet and walked slowly to the lectern. She was known for wearing trousers, then considered a radical act, and all the eyes were on her legs to make sure she wore a skirt. Being aware of the observations she moved slowly to the podium and spoke softly but with absolute clarity.

She argued that Truman should not be given the degree because the University would be seen to be honouring the man who had ordered the bombing of Nagasaki and Hiroshima in which hundreds of thousands of innocent civilians were killed. She argued that the University would appear to be honouring a wicked act and wondered what similar act the university might be thinking of honouring next. Needless to say, the vote went as planned and the motion to award the degree to Truman was carried. But the story of Anscombe’s intervention quickly circulated everywhere in Oxford and was seen as an example of what happens when women are allowed into the university.

All four women participated in movements for political change throughout their lives. Indeed, Iris Murdoch was a member of the British Communist Party whilst at Oxford, and was even accused of being a spy during her Whitehall years. Both Murdoch and Foot remained left-wing, even though they differed in their views and their views softened as they matured. But all of them continued to refuse to accept the easy political reasoning of the war years, as Elizabeth Anscombe’s moment in Convocation House demonstrated. They saw moral philosophy and politics as inseparably implicated in the problems of life, and refused to accept easy subjectivist reasoning about some of the questionable events of war. They regarded the reading of Plato, Aristotle, Kant and Hegel as necessary for thinking through the problems of their day.

Mary Midgley (1919–2018) in 2014, when she was in her nineties, speaking about her most recent book Are You an Illusion? A senior lecturer at University of Newcastle, she produced the first of her 16 books when she was 59 and the last at 99, becoming well-known for her views on science, ethics and animal rights. Photograph: YouTube. To see the full video, see below at the end of the article

Conclusion

.

This is a remarkable book that deserves to be read by a wide variety of people involved in all kinds of work. It is a book for people who think. It is not just a book about four philosophers written by two philosophers for philosophers. It is about friendship and the hope that comes out of reason. It is about the relationship between four extraordinary women that sustained them in difficult times as they did much under-appreciated work. It is also a celebration of young people who aspire to think for themselves and are difficult. Eighty years on, we have never needed such young people as we need them now.

Video: Moral philosopher Mary Midgley argues that the Self is Not an Illusion. Duration 16:57 minutes

Metaphysical Animals was published by Chatto and Windus in 2022.

Sources (click to open)

[1] A. J. AYER, Language, Truth and Logic (Victor Gollanz, 1936).

[2] MARY MIDGELY, Beast and Man: The Roots of Human Nature (Routledge, 1978: revised edition 1995)

We have done our best to obtain permission to use the images in this article, and apologise if we have failed to acknowledge any copyright. If you know of any problem, please get in touch.

Keith Hammond lives on the Island of Greater Cumbrae with his dog Charlie. He is retired from teaching philosophy at the University of Glasgow and for many years has researched Ancient Greek philosophy in relation to problems of modernity.

More News & Views

Don’t Take It Easy

Richard Gault is inspired by Michael Easter’s book The Comfort Crisis and explores the idea of ‘misogi’ during a 600-mile walk across Scotland

Book Review: ‘The Serviceberry’

Martha Cass contemplates the message of a new book by Robin Wall Kimmerer that advocates ‘an economy of gifts and abundance’

Book Review: ‘Conversations with Dostoevsky’

Andrew Watson engages with an innovative new book by George Pattison which explores Dostoevsky’s relevance in the contemporary world

Thich Nhat Hanh & the Poetry of Engaged Buddhism

Philip Brown presents the poem ‘Recommendation’ and comments on the potential of contemplative art to foster compassion

Introducing… ‘Perfect Days’ and ‘Nowhere Special’

Jane Clark watches two films with a contemplative theme

Book Review: ‘Irreducible: Consciousness, Life, Computers and Human Nature’

Richard Gault reviews a new book by Federico Faggin, one of the leading lights of the science of consciousness

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READERS’ COMMENTS

2 Comments

Submit a Comment

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

as usual I have thoroughly enjoyed reading the various articles and learned things I did not know such as the movement to faithfully give birds the names that fit them And learned more about the four accomplished women who made a community for their lifetimes

Your MW article was very fun for me to read and as far as I’m concerned MW can go to hell for giving such a narrow definition of social accomplishment etc. I certainly think of you as socially accomplished in the way that you are a proficient listener, a loving and thoughtful responder in person and also through your skillfully horned poems of delight as well as depth

Thanks so much for your faithfulness in continuing to write this column and for your discerning choice among what must be a wealth of choices

I wonder how much of a Quaker thread ran at some level through these women – Iris Murdoch, certainly, Mary Midgely via James Lovelock, a Quaker, and the Gaia hypothesis, and to some degree the others will have had tangential relations with the Society of Friends.