News & Views

Love Will Not Be Idle: Mysticism and Activism

Jane Clark reports on a timely conference put on by the Mystical Theology Network, and talks to its organiser, Dr Louise Nelstrop

‘The Journey to Freedom’, a travelling sculpture by Wesley Wofford, depicting the African American mystic/activist Harriet Tubman, who was responsible for rescuing many slaves from captivity. Image: courtesy of Wofford Sculpture Studio [/]

Way back in 2017, in the third issue of Beshara Magazine, we reported on a Mystical Theology Network conference which explored the theme ‘Mysticism in Comparative Perspective’. In this, we interviewed Professor George Pattison about contemporary movements which are reinstating the idea that mystical experience transcends the boundaries of religion and culture. The Network has continued to hold annual conferences ever since and this year they once again took on a theme which seems especially relevant to the concerns of the magazine: the relationship between mysticism and activism.

To explore it, more than 100 people converged on St John’s College, Oxford, on 19 March 2024 for a three-day event which featured more than 80 speakers from all over the world. This short report cannot possibly cover the wealth of material that was presented or the richness of the discussions, but hopefully it can give just a little taste of the proceedings, especially as Louise Nelstrop, the organiser, was kind enough to talk to me afterwards about what she thought were the main insights to emerge.

‘St. Catherine cures Matteo Cenni of the Plague’: fresco by Vincenzo Tamagni in the Oratory of Saint Catherine in Siena. Image: via Wikimedia Commons

Mysticism and Activism

. The Mystical Theology Network [/] was started by Louise and Simon Podmore in a relatively informal way in 2012, when she was working at Regent’s Park College at the University of Oxford. She thought it would be good to bring together a group of people who had a shared interest in mysticism, imagining that there might be a dozen or so participants. But about 80 people turned up to the first conference and the project has gone from strength to strength ever since. Its initial focus was on the Christian tradition, but they held the conference on Comparative Mysticism in Glasgow and at this year’s gathering, there were papers on Buddhism, Judaism, Islam, Hinduism and Taoism, as well as a huge range of Christian approaches, from the Desert Fathers to the medieval mystics of Europe and modern thinkers of the 19th and 20th centuries.

The Mystical Theology Network [/] was started by Louise and Simon Podmore in a relatively informal way in 2012, when she was working at Regent’s Park College at the University of Oxford. She thought it would be good to bring together a group of people who had a shared interest in mysticism, imagining that there might be a dozen or so participants. But about 80 people turned up to the first conference and the project has gone from strength to strength ever since. Its initial focus was on the Christian tradition, but they held the conference on Comparative Mysticism in Glasgow and at this year’s gathering, there were papers on Buddhism, Judaism, Islam, Hinduism and Taoism, as well as a huge range of Christian approaches, from the Desert Fathers to the medieval mystics of Europe and modern thinkers of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Louise is now at the Protestant Theological University in the Netherlands after a spell at Glasgow University, but she is also connected to St John’s College, Oxford. She is still the main organiser, fitting in the administrative work between teaching commitments. I asked her about how they came up with the topic of this year’s conference, which certainly seems a very relevant one in the world in which we find ourselves, facing huge problems of war, climate change and social injustice. How should those of us with a spiritual inclination be responding? Should we be stepping into the arena of action in the world, or concentrating on contemplation in the interior?

Louise agrees that the discussion is timely. “It seemed to me that this is an important theme that is often overlooked when we think of the mystical traditions. Although actually, early 20th century theories of mysticism, whatever markers of mysticism they stress, are very concerned with action. Evelyn Underhill in particular mentions active mystics – people like George Fox, Teresa of Avila and Bernard of Clairvaux, Catherine of Siena – who have done some sort of transformative action in the world. So does William James. He tends to emphasise the ineffability of mystical encounter and maintains that the message of the mystic only really has truth for the mystical receiver. Nevertheless, he notices that these people also do transformative work, and praises mystics like Ignatius Loyola, Teresa of Avila, George Fox.

“It is odd, therefore, that in the ways that we have often thought about these people across history, we haven’t really noticed this aspect of activism very much. And I wonder if it’s something to do with the way that we think of spirituality as something very individualistic – personal rather than communal.”

The English mystic Margery Kempe, famous for her spiritual autobiography which recorded her many conversations with God.

Love Will Not Be Idle

.

Academically, the relationship between mysticism and activism is Louise’s own area of special interest, and her paper at the conference was entitled: ‘Love Will Not Be Idle: The Activity of Love in Late-Medieval Mysticism’. “This phrase, ‘love will not be idle’”, she explains, “appears in the writings of a number of mystics of the 13th to 16th centuries, such as Richard Rolle, John of Ruusbroec and St John of the Cross. But it is also an absolutely pivotal idea for Underhill; mystics who don’t make changes in the world aren’t very mystical for her, because she thinks that love is the driving force of mysticism, and Ruusbroec is her favourite writer in relation to this.”

Given that, it is not surprising that several other papers also mentioned Ruusbroec’s approach. Rob Faesen (University of KV Leuven) told us that far from seeing contemplation and action as opposed to one another – or even modes that can sit side by side in a relationship of mutual benefit – Ruusbroec considered that there is an intrinsic connection between them, to the extent that one is actually the completion of the other. In another session, Michiel Vandenbroucke (University of Antwerp) spoke about the concept of the ghemeyne leven or ‘common life’ in Ruusbroec and other mystics from the Groendaal such as John of Leeuwen and Willem Jourdaens. This is the idea that: ‘the contemplative person, from within the abundance of love in his/her union with God, flows out in virtue and good works towards the world’. He went on to show that these great spiritual figures did indeed embody the ghemeyne leven in their own lives by acting as spiritual advisors to the people of Brussels.

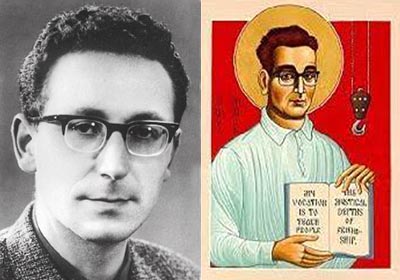

However, it would be wrong to give the impression that the conference was only concerned with the thought of ancient or medieval mystics, wonderful as they are. There were many eye-opening papers on modern mystics such as Egied van Broeckhoven, the Jesuit worker–priest who died in 1967 in an accident in a factory in Brussels where he worked, having devoted his life to the poor and the labour movement. After his death, his colleagues discovered his mystical diary inspired by figures such as John of Ruusbroec and St John of the Cross. Or the Quaker Stephen Hobhouse, who was imprisoned as a conscientious objector during WW1 and went on to develop a theology based on the idea of a ‘no-punishment’ God.

Nor would it be right to limit the idea of ‘action’ simply to participation in social or political spheres. There was a refreshing paper by Claire Wolfteich of Boston University on two female mystics, the Englishwoman Margery Kempe and the African American Jarena Lee, who were separated in time by four centuries but united in that they were both mothers (Kempe had 14 children as well as pursuing an active life of teaching and travel) and also wrote seminal spiritual autobiographies. Whilst Tine Van Osselaer (The Ruusbroec Institute), in her opening keynote address, gave a fascinating presentation on public displays of mystical experience in the form of stigmata or apparitions of the Virgin in Europe in the 19th and 20th centuries. These were witnessed by hundreds or even thousands of people, and elicited profound emotional responses which, she argued, were potentially transformative in themselves.

Cole Arthur Riley, writer, poet and liturgist, author of the best-selling books This Here Flesh and Black Liturgies, who gave the open lecture at the conference

Mysticism and Race

.

For Louise, one of the most important features of the conference were the resonances which became apparent between the different presentations, and between the different spiritual traditions. “I think action is an interesting platform for interfaith discussion and dialogue because it takes us beyond some of the difficulties of talking about things only within doctrinal settings. Of course, whatever a mystic does comes out of some sort of doctrinal setting, but sometimes that can mean that there’s a lot of focus on that aspect, looking for similarities and comparisons and so on. Whereas if you look at the transformed nature of the mystic and how they operate in the world, you can work back from that, rather than starting in a place where there are already differences. For example, the keynotes on the final day by Simon Podmore (Liverpool Hope University) and Dylan Esler (8400 [/]) were on different religions, Dzogchen Buddhism and Judaism, but there was a lot of overlap even though both of them were absolutely grounded in their own tradition”.

The major area where this resonance was explored during the conference was with the African American traditions, because, as Louise explains: “When we consider the topic of mysticism and activism, the driving forces in our own time are coming are from the African American community.” In this respect, it was illuminating to have a contingent from the USA talking about the partnership between black spirituality and activism which has so distinguished the civil rights movements and fights for social justice since the mid-1960s.

There were keynote presentations by Joy Bostic (Western Case University) who discussed the expression of Africana forms of spirituality in black music and dance from the early work songs and spirituals to Beyoncé (an interview with Joy on this fascinating topic will be the next main article in Beshara Magazine) and by Andrew Prevot (Georgetown University). He revealed that the Catholic Church has not yet canonised a single black African saint, although there are six candidates currently under consideration. All these, he explained, lived an apostolic life of activism within their communities, caring for the poor and sick, and were distinguished by also tending to white people, thus embodying what he described as ‘a true universalism which regards all people to be worthy of love.’

There were also short presentations by Byron Wratee (Boston College) on the great theologian and mystic Howard Thurman, and Chanelle Robinson (Boston College) on the 19th century female mystic Harriet Tubman, who, having escaped slavery and found safe-haven in Canada, returned to the USA on 13 separate occasions in order to free others. Then, on the Wednesday night, one of the highlights of the whole event was a public lecture by Cole Arthur Riley, the poet, writer and liturgist, whose best-selling books This Here Flesh [1] and Black Liturgies [2] pioneer an innovative way of expressing spiritual truth through story-telling. “It was especially good to have Cole, as an author and artist, contributing and enriching our understanding because she’s coming at things through a more practical lens”, Louise comments. “I think it added another layer which is not just intellectual. We are very keen to involve artists in our discussions and think about the role of art in the wider practice of mysticism as a whole.”

The subject of mysticism and race was also the topic of a special session on the penultimate afternoon in which everyone, of whatever race or colour, was encouraged to develop awareness of the ways that colonial or racist stereotypes can seep into our understanding of spiritual truth. Louise is particularly appreciative of this session. “Especially at the moment with so many terrible things going on in the world associated with race, I felt quite privileged that so many people from so many different areas of mysticism, across so many different religious traditions, came together to discuss the topic.”

Egied van Broeckhoven, the Belgian Jesuit worker–priest and social activist who died in 1967 in an accident in the factory where he worked.

Spiritual Activism

.

One of the dilemmas that many of us face in the present day is that while we may wish to participate in actions to combat the suffering that we see in the world around us, this often seems to involve taking up a polarised position – an oppositional stance. Whereas it is the essence of the kind of love that mystics like Ruusbroec or Underhill talk about – the love that arises from contemplation of the ineffable and infinite – that it is all-encompassing and inclusive. So I asked Louise how she thought the conference had helped to resolve this contradiction.

“I think that the theology of Howard Thurman, which Byron Wratee talked about, is very helpful in this regard. Thurman says that if you want to bring each person to an awareness of who they are and how we have a shared unity, then you can’t only work for the oppressed. You must also work with the oppressor. Because whatever it is that they’re doing to the oppressed is also blocking them from having a realisation of what they really are. This isn’t a very popular approach. Thurman inspired Martin Luther King Jr in the civil rights movement in the USA. but he’s rather an unknown figure now in comparison to other modern mystics.”

Another point she goes on to make is that there is a different quality to activism when it is undertaken as part of spiritual practice. “It is important to understand that it’s not just that someone is transformed by their mystical insight and then they act. In acting, they are also transformed. So there is something about mystical action that has a potential to bring about a deeper level of transformation in society than social action as such.”

So the final question is: what comes next? Well, the next conference is already planned for June 2025 in Antwerp, and the keynote speakers are booked. The title will be ‘Mystical Entanglements: Community, Relationality, and the Self in the History and Study of Mysticism’. It will pick up a theme which we have already mentioned as an undercurrent in this year’s conference; the idea that mysticism is a communal activity as well as being something that happens in solitude.

I wonder whether this social aspect has become more important to us after the isolation that we all experienced during the pandemic. Louise agrees that it might. “I can only talk personally, but I’ve noticed that I’ve wanted to join more communal things than I did in the past. I’m quite introverted, but I think that I spent so much time by myself during the pandemic that I started to crave company. And so a spirituality that pushes me further into isolation doesn’t feel very appealing at the moment.

“This is another reason why I think that black theologians are very relevant now, because the social aspect has always been a big part of their path, and they have been drawing our attention to this important current within the mystical tradition as a whole. It feels that, like activism, the communal aspect has been a missed theme or a missed mark of mysticism, so I am very much looking forward to exploring it further at next year’s event.”

To find out more about the Mystical Theology Network, including information about next year’s conference, see their website mysticaltheologynetwork.org

Sources (click to open)

[1] COLE ARTHUS RILEY: This Here Flesh, (Hodder & Stoughton, 2024).

[2] COLE ARTHUR RILEY: Black Liturgies (Hodder & Stoughton, 2024).

read more in beshara magazine

Mysticism in Comparative Perspective

Professor George Pattison talks about the revival of a unitive approach

More News & Views

Don’t Take It Easy

Richard Gault is inspired by Michael Easter’s book The Comfort Crisis and explores the idea of ‘misogi’ during a 600-mile walk across Scotland

Book Review: ‘The Serviceberry’

Martha Cass contemplates the message of a new book by Robin Wall Kimmerer that advocates ‘an economy of gifts and abundance’

Book Review: ‘Conversations with Dostoevsky’

Andrew Watson engages with an innovative new book by George Pattison which explores Dostoevsky’s relevance in the contemporary world

Thich Nhat Hanh & the Poetry of Engaged Buddhism

Philip Brown presents the poem ‘Recommendation’ and comments on the potential of contemplative art to foster compassion

Introducing… ‘Perfect Days’ and ‘Nowhere Special’

Jane Clark watches two films with a contemplative theme

Book Review: ‘Irreducible: Consciousness, Life, Computers and Human Nature’

Richard Gault reviews a new book by Federico Faggin, one of the leading lights of the science of consciousness

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READERS’ COMMENTS

6 Comments

Submit a Comment

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

I find that the most relevant mysticism available – to me, at least – lies in the current work by Thomas Hubl, Daniel Siegl, Peter Levine, Gabor Mate, and others whose backgrounds are non-theological, but whose work on trauma opens the way for a path to mystical experience more immediate and directly accessible than anything currently academic. Whole international communities of practice, even of direct intervention ( e.g., The Pocket Project, an arm of Thomas Hubl’s programs), have formed around these leaders because of the directness of the experiences they offer.

Truly appreciate your well-written posts. I have certainly picked up valuable insights from your page. Here is mine Webemail24 about Writing. Feel free to visit soon.

An excellent read that will keep readers – particularly me – coming back for more! Also, I’d genuinely appreciate if you check my website Seoranko about Search Engine Optimization. Thank you and best of luck!

Your posts stand out from other sites I’ve read stuff from. Keep doing what you’re doing! Here, take a look at mine Articleworld for content about about Pharmacy and Pharmaceutics.

Hi there, I simply couldn’t leave your website without saying that I appreciate the information you supply to your visitors. Here’s mine Article Sphere and I cover the same topic you might want to get some insights about Nonprofit Organizations.

No two mystics are exactly the same, even within the same religion. A good example ib Theresa of Avila and her protege St. John of the Cross.