News & Views

Bringing More Land Back to Life

Luci Attala gives an update on the Kogi’s exciting regeneration project, Munekan Masha, in Colombia

A group of Kogi mamas give offerings at an esuama. Photograph: courtesy of the Tairona Heritage Trust

In June 2023, we published an interview with Alan Ereira, about the wisdom of the Kogi Indians, an indigenous people in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta in the north of Colombia. At the time, as Chairman of the Tairona Trust, he was in the process of establishing a Unesco-Most Bridges endorsed project, Munekan Masha, that has the dual aim of restoring an area of land damaged by over-exploitation, and at the same time communicating to Western scientists the unique way in which the Kogi work with nature. We were so impressed with the depth and range of the project that we undertook to keep in touch with how it unfolds.

A year later, we find that Alan has now retired after his 80th birthday and the new Chair of the Tairona Trust is Luci Attala [/], a distinguished anthropologist based at the University of Wales, where she is also the Director of Unesco-Most Bridges UK Hub and Dept Executive Director of the global Bridges coalition that champions transdisciplinary humanities-informed sustainability science. She kindly agreed to talk to us – Richard Gault and Jane Clark – by Zoom from her office in Swansea.

Jane: Can you give us some idea of your own background and how you came to take over from Alan as chairman of the Tairona Trust?

Luci: Well, I’ve spent most of my academic career thinking about social relationships with water. I worked in Kenya in a very rural location, living with a group of subsistence farmers who rely on the rains for their harvest. I started working with them about 15 years ago and I was there at the beginnings of awareness that things were not quite the same anymore – that the waters were changing their behaviour.

Jane: Water is of course central to the Munekan Masha project, which is basically about the regeneration of the water systems in Santa Marta.

Luci: Yes. I had worked with the Trust 20 years ago and was pulled back into it by Alan in 2019 when he was thinking of setting up Munekan Masha. It was right at the beginnings of forming the project, which is, as you say, all about revitalising water in a degraded landscape.

Throughout my career, I’ve encountered numerous indigenous philosophies and ways of thinking, which are always fascinating just by their existence. But there is definitely something a little bit different about the Kogi. When you visit them, which I had the good fortune to be able to do in April with Alan as part of a sort of an official handover, I realised the depths of what was happening. I don’t mean in terms of me taking over, but in terms of the enormity of the task of being able to find a way to communicate what is going on to a Euro–American audience without doing damage to the ideas. These are not easily translatable, so this is going to be an extraordinary task.

Richard: Can you give us some idea of the progress that has been made on the project in the last year?

Luci: Well, part of the reason why we went to Santa Marta was because I had secured money to complete the project as it was originally conceived, but for a variety of reasons, this funding was withdrawn. I was tearing my hair out, panicking about this, but Shibulata and Arregoces, the two Kogi elders that we are mainly in discussion with, didn’t seem fazed at all by it. For the Kogi things always happen for a reason. In fact, they seemed to think it was because something else needed to happen and that the project needed to be redesigned – that it wasn’t quite on point.

They made various suggestions, which we discussed through a series of Zoom calls and emails. But it was quite clear we had to go and sit in the same room and talk to each other to really get a full understanding of what we all meant. The Kogi were convinced that the project isn’t in trouble, but just that it needs to shift its focus. So that’s what we’re doing at the moment. We’re in the process of redesigning it in association with what we’ve been told to include.

Luci Attala and Alan Ereira in the office of Kogi liaison officer Jose Manuel in the premises of the Organisation Gonawindua Tayrona (OGT) in Santa Marta. Photograph: Luci Attala

Munekan Masha

.

Jane: So in what ways has it changed?

Luci: Well, in a nutshell, the previous project saw the Kogi undertake the regeneration of an area of land and, in the process, teach some environmental scientists their methods. We were then going to put that knowledge into educational materials that would be transferable so that people around the world could benefit.

Now it appears that they’ve got even grander designs, and the project is about healing territories outside the Sierra as well as within it. Arregoces provided me with an extraordinary piece of writing in which he articulated, in a way that I think we had not fully understood before, something about the name, Munekan Masha. This text has been translated from the Kogi into English, via Spanish, so you can imagine the problems that can occur there. Nevertheless, I think the new translation is remarkably helpful.

Arregoces previously explained that Munekan Masha can be translated as ‘Let it be reborn’. But his more recent correspondence broke the words down like this,

‘Mu’ refers to the Principle that contains the seed bank of thoughts. ‘Ne’ signifies when something in nature is leaving, being lost, dying, disappearing. ‘Munekan’ is to restore according to ‘Mu’. ‘Masha’ is to care from the Principle of ‘Mu’.

He talks about how there is an original intelligence within a territory – within everything – that allows it to know how to be itself. But as things get disconnected and as territories are not cared for in the correct way, then the entity – you could almost say ‘the personality’ of an area – forgets how to be itself. The processes that the Kogi undertake are designed to remind a territory of its original identity. It is like nursing somebody back to health.

So there’s a personification of a place there, but fundamentally, he’s describing a caring process – a loving process – where one works to remind the territory of who it was originally. Behind it, there is an understanding that there’s already a manner by which everything should manifest, that was created by the original thinker – in their original thought. So part of this is about thoughts and being thoughtful. I think the word ‘thoughtful’ is very useful here because when we describe ourselves as being thoughtful, we are not referencing being full of thoughts or knowledge, we are saying that we’re caring.

This is an extraordinarily profound concept, and I don’t think it can be easily translated into ‘Western’ terms. I think everybody immediately wants to start thinking things like: oh that’s about DNA or something like that. I don’t think that’s a good idea at all. I think it needs to be left as it’s been expressed and not turned into a Euro–American way of thinking about things, because that’s where I think damage gets done to these very poignant and potent ideas. What Arregoces wants is for us to know that there are some things that we can’t understand yet; that this is a very different philosophy.

So that’s one part of the project.

The Kogi elder Arregoces describing the ‘Thought or Land Laboratories’ on a white board in his offices. Photograph: Luci Attala

Connecting Across the World

.

Richard: And the other part?

Luci: It is, of course, buying land back. The more land that’s bought and returned to the Kogi, the quicker things can heal. Arregoces talked about the importance of this at length. He said, look, you always talk in terms of sacred sites, but it’s not about sacred sites. There are areas – sacred or important areas. We cut up territories with fences and national boundaries and with our maps and so on when in reality, it’s one territory. So as the Trust buys parcels of ancestral land, the Kogi are seeing the restoration of a body. This means it’s not simply about accumulating territory with special sacred points, but about sacred areas cohering. And once healed, these will remind each other of how to be healthy or themselves again.

Jane: So the effect of healing is contagious?

Luci: Almost. What they are saying is that places influence each other through the energetic lines that connect them. For the Trust, what this means is that now there’s a bit of a rush on to get not just one territory, but more, so that we can accelerate the healing that the Kogi are desperate to do. They want to have a family living on each territory to ensure that that process continues and the land is protected.

And more than this: they want to connect with territories abroad. Arregoces wants to have what he calls ‘thought laboratories’ in other locations so that they can connect up and the healing can transmit across the lines that are created between territories.

Richard: Are these territories in South America and Central America or worldwide?

Luci: Throughout the world.

Jane: Do they have to be indigenous territories?

Luci: Not necessarily. No. So let me just change direction slightly and tell you a story that might explain why I’m embracing these extraordinary ideas without questioning, interpreting or even understanding them. I’m an academic and obviously I’ve been trained in rational thinking, and even though I’m an anthropologist and I encounter all sorts of different belief systems, I always have to write in such a way that makes sense in terms of linear thinking. But right before I went to Colombia in April, I had the most extraordinary dream of a sort I had never had before.

I was walking up a mountain. It was quite barren, and I was having a slight argument with people, saying that there would be snakes and that we were going through the wrong place. And, sure enough, I was proved right, as the mountain cracked open, and the most colossal snake appeared out of it. Everybody ran to kill the snake. I ran as well, but when I encountered the snake, she turned into a woman, and she just started talking to me. She told me various things and she also gave me a basket of bread, and then the next thing I knew I was down at the bottom of the mountain. I reached up to her and she became the top of the mountain and her eyes turned into these pools, crying down onto me.

I woke up with the most enormous feeling of relief, and I thought: thank God, someone’s looking after me. Everything’s going to be fine now. I don’t usually wake up with that feeling!

This dream was a very meaningful moment to me, but I didn’t understand it. So I asked various people about it, and both I and they had ideas about what it might mean. But when I got to Colombia, I found that Shibulata, the spiritual elder, already knew I’d had the dream and he told me what it was about. He named the snake. She’s my original mother, apparently, and my original mother has been talking to his original father and they’ve been communicating.

I had been told to bring an offering to the Kogi – you always have to bring something – and I had brought two small crystals, little stones that I had, and I offered them to him. He said: ‘These aren’t for me. This is what our ancestors have been discussing. We need to make a connection between Colombia and Wales.’ So he put the stones onto the ground at his feet and, well – I don’t know what he did; it involved using his poporo and so on! But he told me that the mountain had received them, that he had activated them and I had to take them home, put them on the land to form a connection. And that was the first time that I realised you can connect up territories in a way that echoed some of the symbolism in my dream.

Then the next day, Arregoces spoke about the idea of thought laboratories and connecting them up. I told him about my dream afterwards, and he said: ‘It was a message. We have to do this project’. So I’m now in a situation thinking, OK, we have to do this. Come on, ancestors, help!

Waterway on Kogi land in Santa Marta. Photograph: Tairona Heritage Trust

Getting the Project off the Ground

.

Jane: So what is the next step?

Luci: Well, I am currently working to rewrite the idea into an academic project that will allow us to present it to potential donors. Funders need you to quantify things, to say how long you’re going to do something for and how many people will be involved.

As a result, shaping these radical ideas into the form of a proposal is taking time – longer than I hoped. Then I have to send it back to Arregoces and the Kogi will comment on it, and I’ll rewrite it, and we’ll do some back and forth until we finally get it shaped up in the way that works for the Kogi. It has to work for them. If it doesn’t make sense to, say, an academic audience or to a mind that’s been schooled in a Euro–American extractive way of thinking, so be it. After the dream, I feel I have to trust the process and not let my head get in the way of it.

We are definitely at a point in history – I’m sure you can feel it too – where things are really ramping up. We need to accelerate. We need to take risks. We need to be bolder and braver. We can’t be trying to fit in with the previous structures – they haven’t worked.

Jane: I absolutely agree with you about this ramping up. Global warming has been much faster than we anticipated thirty years ago and we had the news just this year from the UN that we have, from their point of view, passed the ‘tipping point’ to reverse the damage that it is causing. The Kogi’s message has always been that it’s not too late to do something. Do they still feel that?

Luci: Well, apparently, part of the reason why they want to do Munekan Masha is that they are concerned by the amount of healing that needs to be done and want to create change in our behaviour to slow the damage. But they never say it’s impossible to turn the situation around. They never, ever seem to say that.

But the good news from our side is that at our most recent meeting, the trustees of the Tairona Trust agreed to go ahead and purchase land before the project is fully outlined. This is to affirm our commitment to Arregoces’ wishes for more land to be returned to the Kogi people and also to act as a catalyst to move the project on. Immediately, we received a pledge to match fund donations received so that we can purchase land to get us off the ground again.

Establishing Communication

.

Richard: In the original article in Beshara Magazine, Alan really stressed – I think this would be the right word – the problem of communication. I am sure you are familiar with the idea put forward by Thomas Kuhn of ‘paradigms’ [1] – which are total world views which determine the way we see things. If you are operating under one paradigm and I’m in another, then it is almost inevitable that we’re going to misunderstand one another. So he saw Munekan Masha as, in a sense, a way of solving this problem of communication.

Luci: You are right that setting up a relationship or a dialogue between these two very different philosophical or ontological approaches is a challenge and has to be done with incredible sensitivity for a range of reasons.

That dialogue has already begun, of course. I think there have been some serious misunderstandings along the way, but it is good to see these as learning points, not problems but rather, illustrative of the processes we need to go through to really understand each other better. I think now we’re in a much stronger place, and that an ability to communicate is being created above anything else. That’s an enormous advance, but there’s still a lot of work to be done.

In the academic community and around the world, indigeneity and indigenous knowledge generates a lot of interest. But unless you’re working directly with the people and adopt a very humble position in doing so, it’s easy to alter or translate what’s being said into something that makes sense to one’s own way of thinking. To avoid this, we are going to attempt to first establish points of similarity between our different approaches and then, using those, work out what might be required to enable Kogi techniques and philosophy to be adopted by the mainstream. This is about uniting and, by joining, improving practice.

Jane: What strikes me about what you are saying is that the need to care for the land is at the centre of this project.

Luci: Very much so. It’s going to take a mental revolution, or the paradigm shift mentioned earlier, for people to understand how to care for the world. It’s not about mowing the lawn and making ‘nature’ look tidy, and it’s not simply organic farming either. The Kogi appear to have different understandings of what caring for the world means. It’s not just a mental matter – having the right thoughts and doing the correct actions. It is a matter of the heart. Imagine if somebody was ill and you needed to care for them – you wanted to nurse them back to who they really are. You might be able to achieve that by simply completing tasks. But if you care, that care emanates out of you, and changes the ‘energy’ of your actions because they come from your heart.

That’s the kind of caring that I think the Kogi have for the world. They love it – really love it – literally. We don’t. We just use it.

Richard: Can we ask about the book Shikwakala, written in 2018? In the interview with Alan a year ago we learned that the Kogi didn’t want to publish the book because they were worried it could fall into bad hands.

Luci: They haven’t published it, but they are giving out copies of it with increasing frequency. I see them giving them out. It’s only in Spanish; it’s not translated into English yet, and I think that will be a significant endeavour. So that hasn’t happened.

Jane: Is it still part of the plan for academic observers to witness and monitor the process of regeneration? In fact, are you one of these observers?

Luci: Yes, and yes, I will be one of them. We’ve got a team of anthropologists, translators, ethnobotanists, ecologists and biodiversity experts, topographers, technicians and even some satellite data scientists to track and monitor the changes that take place. As you know, there’s anecdotal evidence that land in Kogi ownership shows remarkable ecosystem repair in a relatively short period of time. Restoring degraded land can take as long as 4000 years but work in the Amazon, thankfully, shows that this can be accelerated to as little as 65. The Kogi method, on the other hand, achieves something similar in only 30 years.

Munekan Masha is going to differ from other collaborative ventures because we are going to work together to learn how to identify the features in the landscape that qualify as ‘sacred’ or as the operative spaces that the Kogi maintain regulate areas. We are hoping that the Kogi will teach us how to understand these features and their broader role in maintaining the health of the place. I anticipate that a dramatically different perception of ecology to that of environmental science will emerge – not least because we will have to comprehend the vast weave of connections that the Kogi say enable natural processes to flow across regions and around the world.

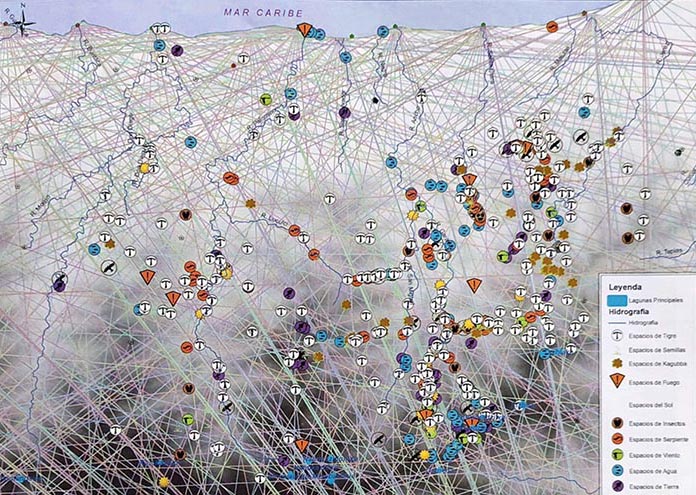

Richard: You are referring here to the ‘black lines’ that they draw out in Shikwakala which form a kind of network of invisible ‘threads’ connecting places to one another? [See the original article for more on these]

Luci: Yes. In Shikwakala they explain this network as it appears within the Sierra, but my understanding is that it also extends beyond the area, across the world.

Going Around the World

.

Jane: Are they going to also monitor your area in Wales, which is presumably one of the territories that they’re making connections to?

Luci: Well, yes, they’ll have to. So one thing that Arregoces says is that Kogi need to go around the world. I was really surprised when he said that. There has already been one project where an anthropologist took a Kogi elder to some of the sacred sites of the world – in India and Malaysia – but I think there’s an opportunity now to take Kogi not just to already designated so-called sacred sites, but to wherever they want to go.Jane: And have they named any sites they have in mind?

Luci: Not yet. But I suspect they know where they want to go. There is another lovely thing that you should know about. You know that Alan made the two films A Message from the Heart of the World [/] [2] and Aluna [/] in order to alert us – ‘the younger brother’ – to the damage we are doing to the world? Well, the Kogi have decided to keep sending out the message – that it’s important that they keep sending it out – but now they’re doing it in two different ways. One is through Munekan Masha, which is going to be an amazing adventure, and the other one is through an extraordinarily beautiful dance and song performance that they have designed called Shikwakala: The Roar of Mother Earth.

When I first heard about this, I said: ‘What!? I didn’t know that the Kogi were singers and dancers. That’s not been mentioned anywhere before.’ But, apparently, they have very graceful and beautiful dances and songs, and have decided that if the films, books and words don’t reach us, the younger brother, they’re going to dance and sing in the hope that the message touches our hearts.

So at the moment, as well as everything else, I’m trying to raise funding to send this performance around the world. They need about £100,000 to get their troupe on the road. The plan is that they will begin with a national tour in October 2024, starting in indigenous communities in Kogi territory before showcasing at the United Nations COP16 Biodiversity summit in Columbia. Then, if the funds have been raised, they will do an international tour.

Jane: Luci, thank you so much for speaking to us about this remarkable project. We wish you well with it and look forward to speaking again in another year to find out how it is progressing.

To learn more about the work of the Tairona Trust and Munekan Masha, see their website: www.taironatrust.org

To read last year’s interview with Alan Ereira in Beshara Magazine, click here

This is the video of a talk that Alan gave in the Munekan Masha project in 2023.

Sources (click to open)

[1] THOMAS Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions [/] (University of Chicago Press, 1962).

[2] ALAN EREIRA, The Heart of the World (Jonathan Cape, 1990).

More News & Views

Don’t Take It Easy

Richard Gault is inspired by Michael Easter’s book The Comfort Crisis and explores the idea of ‘misogi’ during a 600-mile walk across Scotland

Book Review: ‘The Serviceberry’

Martha Cass contemplates the message of a new book by Robin Wall Kimmerer that advocates ‘an economy of gifts and abundance’

Book Review: ‘Conversations with Dostoevsky’

Andrew Watson engages with an innovative new book by George Pattison which explores Dostoevsky’s relevance in the contemporary world

Thich Nhat Hanh & the Poetry of Engaged Buddhism

Philip Brown presents the poem ‘Recommendation’ and comments on the potential of contemplative art to foster compassion

Introducing… ‘Perfect Days’ and ‘Nowhere Special’

Jane Clark watches two films with a contemplative theme

Book Review: ‘Irreducible: Consciousness, Life, Computers and Human Nature’

Richard Gault reviews a new book by Federico Faggin, one of the leading lights of the science of consciousness

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

READERS’ COMMENTS

0 Comments