News & Views

Consciousness and the Computer

Richard Gault reviews Jeremy Naydler’s book ‘In the Shadow of the Machine: The Prehistory of the Computer and the Evolution of Consciousness.’

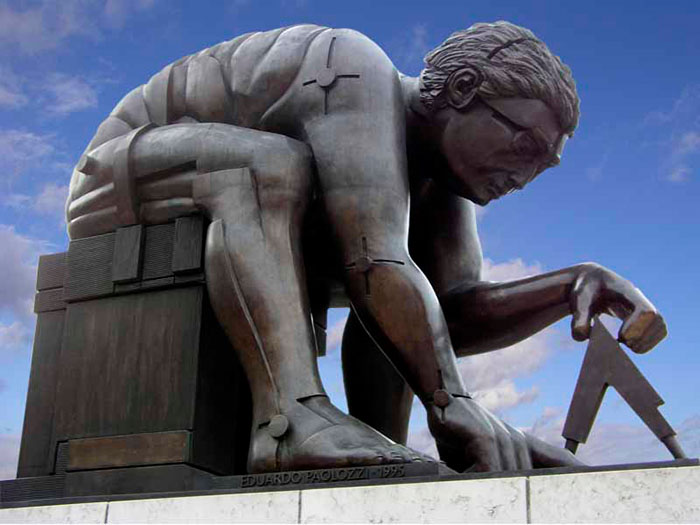

‘Newton after Blake’ by Eduardo Paolozzi, outside the British Library in London. Photograph: Wikimedia Commons

We are conscious when we are conscious, yet we are rarely conscious of being conscious. Even more rarely do we question our consciousness, but this is what Jeremy Naydler has done, and done remarkably well, in this meticulously researched book.

It is through consciousness that we come to know ourselves and the world. What is it to be human? What is this world we find ourselves in? These are questions that have been posed since the most ancient times and they can neither be asked nor answered without there being consciousness. Indeed, the answers are bound up with the nature of the consciousness that is prevalent within any particular society or civilisation. As Naydler shows, the fact that the ancient Egyptians and contemporary thinkers give varying answers reflects fundamental differences in their consciousness. There has, of course, been feedback: new answers effect changes in consciousness, which in turn yield other answers. Naydler, whose previous books include studies on Goethian Science and Ancient Egyptian spirituality [1], skilfully charts these changes and effects over millennia, from Pharaonic Egypt to the present day.

The ancients saw themselves as souls manifested. They understood the world to be a living being formed by meaning; knowledge was gained by contemplation. By contrast, the generally held current view is that the world and ourselves are mechanistic, material things best understood by reason. The apotheosis of this move from the divine to the soulless is revealed, Naydler argues, in the computer. Clearly non-organic, the computer both provides and reflects the contemporary model for understanding consciousness and does so while offering us virtual worlds which remove us even further from natural reality.

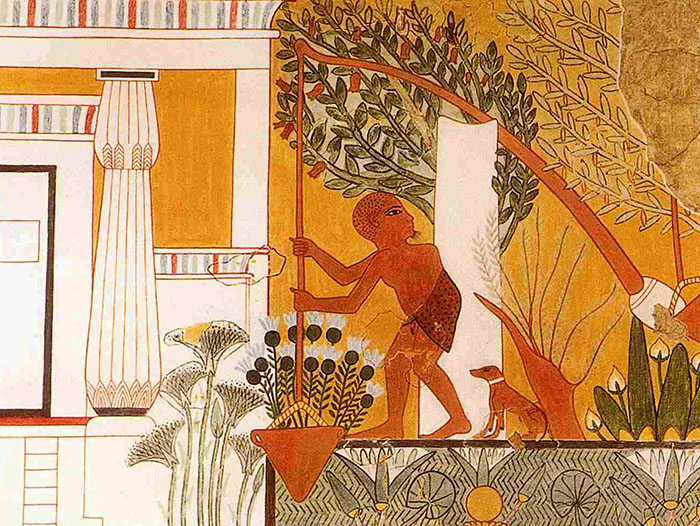

Egyptian gardener using a shaduf. Tomb of Ipuy at Deir-el-Medina, west bank of Thebes. Image: The Picture Art Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

Logic and the Computer

.

Naydler argues that whilst the computer has entered the world as a result of modern science and technology, these are themselves manifestations of the type of consciousness which has taken millennia to develop.

The range and depth of Naydler’s investigation is vast. He identifies and brings out the significance of key, often little-remarked changes in thinking over the past four millennia, such as the changing role of language. In doing so he offers new, insightful perspectives. For example, he asks: what is a machine? The Cambridge Dictionary offers: “a piece of equipment with several moving parts that uses power to do a particular type of work”. Naydler sees the matter differently, maintaining that “Machines should be viewed as essentially logical thought patterns exteriorised in physical form” (p. 77). In other words, machines betray the consciousness that brings them about. A civilisation whose consciousness is not governed by logical thought will not – indeed cannot – create machines.

A more fundamental question is: what is it to know something? For the ancients, Naydler says, to know something was to directly comprehend the idea inherent in the formation of a thing – its essence. Knowledge was sought and expressed in qualitative, often moral terms. The change to objective knowledge which can be quantitatively (ideally mathematically) formulated and which is normally valued for the way in which it can be used, has a long history. Though its beginnings are discernible in Ancient Greece, science really took root through the work of Bacon, Galileo and Descartes. But does the modern form of acquiring knowledge actually result in real, true knowledge? Naydler dares to ask. He goes on to argue that science yields knowledge, and is content to do so, about things, but not knowledge of things as they are in themselves.

This relatively new form of knowledge and the associated appearance (indeed possibility) of machines resulted eventually in the invention of the computer in the twentieth century. Naydler reveals the importance of weaving looms in its evolution. They were an important precursor because they were the first programmable machines. Almost 300 years ago, patterned silk cloth was being woven in France on looms guided by instructions on perforated paper. A hundred years later, punched cards had replaced the paper, and it was the genius of Charles Babbage to recognise that they might be used to program more than looms.

Thus, in 1834, through Babbage, the idea of the computer was born. However, it was more than a century later that the first computers appeared. Why the delay?

Few of us may know how a computer actually operates in any detail. However, we all know that in order to work our laptop has to be connected to an electrical power source and switched on. Computers need electricity and, essentially, Charles Babbage’s Difference Engine and Analytical Engine were stillborn for the want of electricity: mechanical power would not do. So an answer to Naydler’s central question of what brought about the computer is – it was electricity.

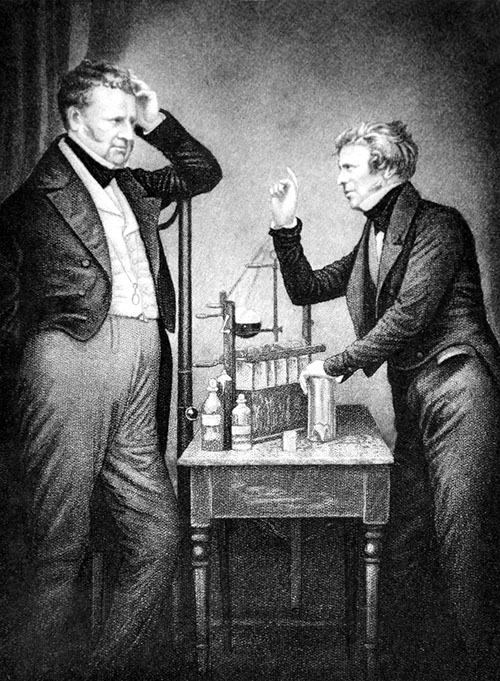

Nineteenth-century pioneers of electricity, Michael Faraday (right) and John Daniell (left) in the laboratory. From Sketches of the Royal Society and Royal Society Club by Sir John Barrow

Electricity and the Binary

.

Electricity is so ubiquitous in our lives that it is easy to forget how novel and how extraordinary it is. Without it, our lives would be radically different and computers impossible. Yet its power is mysterious; we cannot witness it in the way we can water, wind or even steam power. So how was it discovered and harnessed? It needed the shift to the scientific way of seeing the world, which views nature as something to be manipulated. It also required the related acceptance that it is enough simply to know about something, even if we don’t fully understand it. Naydler describes the concerted experiments which began with magnetism in the thirteenth century and which culminated in the nineteenth century in the technology that yielded the means of generating and harnessing electric power. It was seen as a useful new source of energy, which could be employed without questions about its true nature ever needing to be answered, as one of the early pioneers, Heinrich Hertz himself admitted:

To the question, ‘what is Maxwell’s theory?’ I know of no shorter or more definite answer than the following – Maxwell’s theory is Maxwell’s system of equations. (p. 273)

Here functionality trumps understanding; Bacon’s epistemology is vindicated.

Electricity drives the computer but a subtler sort of power lies at its heart. As a machine, the computer ‘exteriorises’ the binary. A computer works, and can only work, because it stores information as bits, binary digits. Changes in the information stored or represented come about because of binary changes in the flow of electrical current – the switches from current flowing to not flowing through its circuits.

For us the logical thought pattern of the binary is so normal that it goes unremarked and unquestioned. Our days are a series of encounters with it: alarm on, alarm off; light on, light off; kettle on, kettle off; door locked, door unlocked; do this or do that; yes or no; true or false. The binary is commonplace, but is it natural?

Naydler shows our unquestioning acceptance of the binary to be misguided. The binary has a history whose faint beginnings he traces back to the emergence of the technology of the simple shaduf – a lever for lifting water – in the third millennium BCE in Mesopotamia. The shaduf has two, binary ‘states’: it is either up or down. The binary subsequently crystallised into the logic first formalised by the Greek philosophers, which would ultimately become scientific reasoning.

There are cultures, stretching from the Pythagoreans to the hermetic traditions of the Renaissance, that regard the number two as a symbol of evil. The Egyptians, for instance, resisted the binary shaduf for a thousand years, only bringing it into common use in the eighteenth dynasty (about 1300 BCE). Naydler also cites the sixteenth-century Belgian philosopher Gerhard Dorn, who drew attention to the fact that in the first chapter of the Bible, Genesis, the second day – the day the waters are divided – is the only day that God does not see that “it was good” (p.145). Within these traditions something could be this, that, or both this and that: three possibilities, and the number three (trinity) itself (along with one, standing for unity) was regarded as inherently good. A computer could not have arisen within such a tradition and its consciousness, Naydler argues.

Punched cards for weaving machines, in the former textile factory (soft furnishings) Vanoutryve, rue du Phénix in Mouscron, Belgium. Photograph: Jemail via Wikimedia Commons

Ways forward

.

Naydler is clearly unhappy with the consciousness that has brought the computer. His plea is to rediscover meaning in ourselves and the world. Ironically, perhaps, electricity may have opened a way forward. For, in his final chapters, he begins to explore how electricity has facilitated the questioning of the nature of reality by scientists themselves.

In endeavouring to understand electricity and in using it to further scientific investigation itself, scientists have come to understand that we do not actually live in a material universe. Trying to explain electricity led to the discovery of ‘fields’ (electro-magnetic fields, gravitational fields, radiation fields …), which are not material in the traditional sense. What the atomists posited long ago has proved upon investigation to be a false grail, as the nineteenth-century pioneers Faraday, Maxwell and Hertz perhaps suspected and the twentieth-century Bohr and Oppenheim certainly came to understand. The quantum universe which we now know underpins the ‘material’ world is itself neither material nor binary: Schrödinger’s cat [/] is both dead and alive.

Naydler has done great service in informing us of where we are, explaining how we got here and offering some hints of where we might yet go. His general advice is to re-appreciate the value of knowledge gained by contemplation. Above all, he concludes: “today […] it is imperative to articulate how we differ from machines.” (p.286)

More particular and novel is his plea to understand the metaphysics of electricity:

What is needed today is […] knowledge of electricity as a spiritual power with distinct moral qualities […]. [This] would be a different kind of knowing based on a very different philosophical perspective, which would be able to encompass the moral and spiritual dimensions of the natural order which, since the seventeenth century, it has been the central project of mainstream science to exclude. (p. 278)

This is a marvellous and erudite account of the history of consciousness. It is supremely well illustrated, and where necessary complex technology is simply and brilliantly explained. Do read this book and feel your consciousness pricked.

— — —

In the Shadow of the Machine: The Prehistory of the Computer and the Evolution of Consciousness by Jeremy Naydler was published by Temple Lodge [/] in 2018.

Dr Richard Gault has worked at universities in Scotland, Ireland, Holland and Germany, where he has taught and researched a variety of subjects, including the history and philosophy of science and technology

More News & Views

Don’t Take It Easy

Richard Gault is inspired by Michael Easter’s book The Comfort Crisis and explores the idea of ‘misogi’ during a 600-mile walk across Scotland

Book Review: ‘The Serviceberry’

Martha Cass contemplates the message of a new book by Robin Wall Kimmerer that advocates ‘an economy of gifts and abundance’

Book Review: ‘Conversations with Dostoevsky’

Andrew Watson engages with an innovative new book by George Pattison which explores Dostoevsky’s relevance in the contemporary world

Thich Nhat Hanh & the Poetry of Engaged Buddhism

Philip Brown presents the poem ‘Recommendation’ and comments on the potential of contemplative art to foster compassion

Introducing… ‘Perfect Days’ and ‘Nowhere Special’

Jane Clark watches two films with a contemplative theme

Book Review: ‘Irreducible: Consciousness, Life, Computers and Human Nature’

Richard Gault reviews a new book by Federico Faggin, one of the leading lights of the science of consciousness

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

Sources (click to open)

[1] Other books by Jeremy Naydler:

Goethe on Science, Floris Books, 1996.

Temple of the Cosmos, Inner Traditions Bear and Company, 1996.

Shamanic Wisdom of the Pyramid Texts, Inner Traditions Bear and Company, 2005.

The Future of the Ancient World, Inner Traditions Bear and Company, 2009.

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READERS’ COMMENTS

1 Comment

Submit a Comment

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

Very interesting and well developed. I will certainly look at his books. Thank you