News & Views

Charlotte Maberly investigates an innovative project which explores cultural engagement as the driver of ecological change

Issues of our climate crisis are now widely understood, and yet the action required to address the problem remains elusive. Could the missing driver for change be cultural rather than scientific? In this interview, I speak with Emily Cropton, a member of the team delivering Connecting Threads – a cultural project of impressive scope being launched this year along the River Tweed in southern Scotland. The project seeks to celebrate and protect this vital natural resource through diverse cultural engagement over five years, combining environmental stewardship with creativity and the arts. I learn why this innovative approach may provide the insight and empowerment we need in the face of climate change.

Charlotte: Connecting Threads will be launched this year with a full programme of cultural activities focussed on the River Tweed. It is happening in the context of heightened awareness of the climate crisis within our society. Do you sense there is an appetite for this kind of approach at this time?

Emily: Yes, this feels like a vital moment to be working on this project. Since the Covid pandemic there has been an increased awareness of how valuable our natural environment is, not just as a place we can go and walk but as key to our physical and mental wellbeing. At the same time, TV programmes such as Wild Isles, and the rising popularity of outdoor pursuits like wild swimming are raising awareness that nature is in crisis. It has been reported recently that 100 per cent of rivers in England are now polluted. Although it is important that we acknowledge shocking statistics like this, the individual can feel powerless in the face of such information. This can lead to overwhelm and disengagement, which is the last thing we need now.

Emily: Yes, this feels like a vital moment to be working on this project. Since the Covid pandemic there has been an increased awareness of how valuable our natural environment is, not just as a place we can go and walk but as key to our physical and mental wellbeing. At the same time, TV programmes such as Wild Isles, and the rising popularity of outdoor pursuits like wild swimming are raising awareness that nature is in crisis. It has been reported recently that 100 per cent of rivers in England are now polluted. Although it is important that we acknowledge shocking statistics like this, the individual can feel powerless in the face of such information. This can lead to overwhelm and disengagement, which is the last thing we need now.

So the aim of Connecting Threads is to encourage a sense of relationship and agency through creative engagement with nature – in our case, focussing on one particular river and its surrounding environment.

Charlotte: Culture is so often seen as separate from environmental studies and environmental activism. But you are taking a completely different approach and putting cultural engagement first.

Emily: We cannot care for something unless we have a relationship with it. We understand the science behind climate change but it seems that having scientific knowledge isn’t enough to make us act. Physically engaging with the environment is the most effective way of creating our own stories and emotional connection to the natural world. These are the ways in which meaningful and lasting relationships are formed.

River Culture

.

Charlotte: You are centring your work around the River Tweed. Can you say why you chose this particular environment?

Emily: The River Tweed is a long – 156km – and complex waterway which reaches across Southern Scotland and Northern England. It is a huge asset to the area, economically, ecologically and aesthetically. It draws large numbers of tourists into the region, and is deeply loved by locals. But like the vast majority of rivers in the United Kingdom, it has been negatively impacted by pollution, development, mismanagement and the wider impacts of climate change, so one aspect of the project is to draw attention to this.

Connecting Threads is actually part of a much larger landscape scale initiative called ‘Destination Tweed’, which is taking place across Dumfries and Galloway, the Scottish Borders and north Northumberland. This has funding of £25 million over the course of five years. The spine of the Destination Tweed project is the creation of a long-distance hiking trail down the length of the river. We will be drawing on the symbolism of that journey from source to sea, creating connections across the landscape and between communities.

As with most places in the world, this region’s population has grown around the river’s edge and so the Tweed connects many communities within the Scottish Borders and neighbouring regions. We will use the river as a tool or framework on which to place cultural activities that help people here feel part of something bigger – not just individual towns and villages, but a community across a whole water catchment area.

Charlotte: The river passes through many of the major towns of the region – Selkirk, Melrose, Kelso, Coldstream and of course, Berwick-upon-Tweed – all of which have their own histories and particular cultures. But in your manifesto you talk about ‘river culture’. Are you suggesting that there is a kind of culture located in the river itself which these places have in common? Or is ‘river culture’ something you will create?

Emily: If we understand culture as the ways we interact with and derive meaning from the world around us, then river culture refers to the routines, traditions, beliefs, activities, and land management practices, that tie us to the river. So, that could be anything from walking a dog by the river’s-edge, to performing a river blessing, or the way a farmer uses the water on their land.

Across the UK, river culture has been heavily influenced by only a few industries for several hundred years. Along the Tweed this has largely been textile and paper–making factories, and of course agriculture, all of which present ongoing challenges of pollution. But they also dominate river culture by preventing or discouraging other uses. The Tweed also has a long-standing history of salmon fishing which is of cultural importance to the area. The fishing population has a strong voice because of the economic activity generated for the estates that own the river-banks. If we are to ensure balanced and beneficial environmental stewardship into the future, it is important that a more diverse sense of ownership and engagement be encouraged.

Charlotte: The use of the river by these industries must have changed a lot in recent years with the decline of manufacturing in the UK.

Emily: Yes, today, many UK industries are facing change and decline as the resources on which they rely become scarce or untenable. So we must seriously consider what alternatives there are for our communities and our natural environments. Finding out what is best for people and planet could be a challenge, as we are entering unchartered waters. This is where creative and cultural approaches could help us reimagine the river culture here, as it could our relationship with nature anywhere in the world.

One key aim of Connecting Threads is to give people more opportunities for direct interaction with the river in ways that involve imagination and creativity. We hope to provide experiences where people can have some kind of embodied understanding through engaging physically with the river. This is a way of acknowledging current river culture, and re-creating it as is needed by the human and non-human communities that live here.

Physical Engagement

.

Charlotte: How will the project create and support cultural engagement with the river?

Emily: We have a five-year framework in which we will work across all art forms, from visual and performing arts, to music and poetry. The programme is intended to be diverse so that we can engage broadly and harvest a spectrum of expressions. We intend for each location and season to guide us, to let the voice of the river and its environment speak.

We will hold a range of public events and workshops and some of these will be quite physical in nature; they will involve people being on, in or by the water, engaging through dance, walking, canoeing, observing and recording, as well as citizen science. Three artists a year will take up residence within a habitat such as woodland or meadow, and other spaces that relate to the river. We will also have regular river conferences for more focussed discursive activity, as well as training opportunities, annual paid internships and opportunities for volunteering. Finally, there will be a mapping or tangible collection of river culture to communicate findings into the future. It is an ambitious programme!

Charlotte: You have mentioned the idea of physical engagement. Why do you think this is so important?

Emily: I find it interesting to imagine the river catchment as a body, as a way of understanding it on a deeper level. The river is interdependent upon its environment to feed it, shape it, and keep it healthy, just as people are upon their surroundings and community. The river is living and moving, and changes every day; just like we do. Engaging physically with the river is an experience which you can then embody within you.

It is not about anthropomorphising the river; it’s about helping people understand that it is not just scenery. Until we can see our landscapes as living systems and feel the possibility of interacting with them, we won’t be able to look after them. After all, you don’t look after a living system in the way that you look after picture on your wall.

Charlotte: I love that idea and had never thought about it that way. You have also mentioned creative placemaking as a key component of your approach. Why is this particularly suited to this project?

Emily: Place-making practise has been happening for a long time and is particularly referred to within professions such as urban planning, landscape architecture, and other areas of design. My understanding of place-making is that while we can physically create space by constructing buildings or whole housing estates, etc., these are physical spaces but not ‘places’. Place-making is creating the intangible layers which are beyond the physical structure of an environment. How we transform a physical space into what we might describe as a ‘place’ – that is, somewhere people feel a sense of belonging, agency and responsibility – is the focus of creative place-making. It is in ‘places’ that cultural understanding is created and conveyed, and in which we make meaningful connection with our world.

Creative place-making in the context of this project is about giving people ways to transform the river from being just a beautiful physical environment to being animated by layers of activity, social significance and cultural meaning. This will happen differently for everyone, but hopefully it provides more people with a way to see the river – and nature beyond – as a place in which we can all participate.

Instigating Change

.

Charlotte: Is it fair to say you feel it is important to try and instigate change here, but you have not determined exactly what that will result in?

Emily: Yes. The project is only funded for five years – a very short period in the context of a river, perhaps. But with the time we have, we aim to sow the seed of an idea which we hope will grow; reframing the river as the core thread which ties us to each other and to our environmentI’m not afraid to acknowledge that it is going to be very challenging to measure success – a challenge that most cultural projects face. If you look at the wider Destination Tweed project, there are going to be some very tangible impacts which include the new walking trail, thousands of trees planted in the upper Tweed, a tributary of the river will be re-meandered, pollinator habitat restored, and many educational programmes will be delivered. But how then do we measure the cultural impact of Connecting Threads? Some of the work we do might have an impact well into the future – as a child grows up, for example, or as a critical mass of momentum builds around an idea. This could make it challenging during the project to know whether we’re heading in the right direction.

The idea of embodied experience is most important, in my opinion, because this is what helps people create a memorable and unique encounter with nature, with the river and its environment, which is how relationship starts. It can leave a lasting impression which changes how people feel and behave long into the future.

Charlotte: Perhaps the exact destination is not one you can describe yet, but do you have a sense of what success will look like for this project?

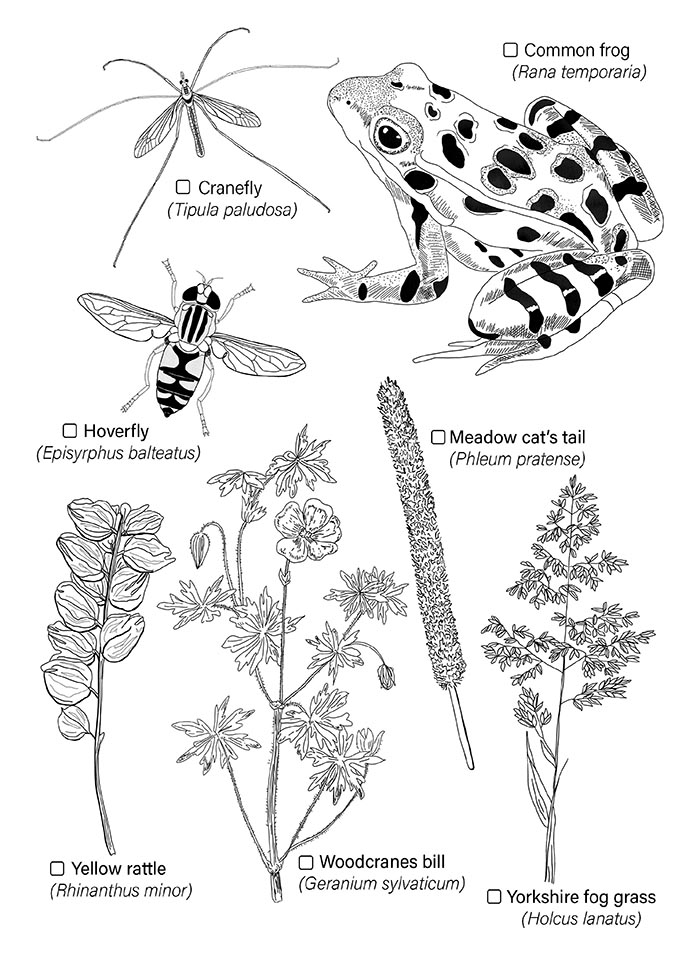

Emily: I really like the image conjured by Jules Bradbury, an artist in residence during our trial year, and think success would look like a healthy meadow – an open space where a diversity of species is held in balance. The analogy between the meadow and our project is that we want to see a healthy diversity of voices. A meadow, or species-rich grassland, is a managed landscape. It needs people to intervene and care for the balance. If Connecting Threads is to create a ‘meadow’, then we have to ensure that diverse voices are heard – not only people, but other species, too. We need to avoid dominance of any one voice, including the human over non-human ‘voices’, because humans find it hard to hear these entities.

The question we need to consider is: how do we as a team support this flourishing of diverse voices? We have taken time to identify marginalised groups in these regions; those who might not have access to cultural activities, and we have considered who might be socially or geographically isolated and excluded. We are also paying particular attention to younger people, as the opportunities available for younger demographics are very different in rural spaces compared to cities. It is important that their voices are included and heard.

Kayaking on the river in the estuary at Berwick-upon-Tweed. Photograph © Copyright Walter Baxter [/], licensed under the Creative Commons Licence [/]

A Unifying Force

.

Charlotte: You have spoken about the universal thread of the river. Do you think that the river is, or could become, a unifying force or presence? And if so, what would the impact be on the region and communities here?

Emily: I hope that part of the impact would be less conflict along and around the river. Right now, there are people looking after the river water quality, but water companies are allowed to release pollution into the same water. This is a problem not only on the Tweed but all over the UK.

You also have a very vocal group who fish on the river, who seem to be in conflict with those hoping to use the river for other activities. So it can become quite territorial. Of course, territory takes on additional significance when working along a border where the acquisition or loss of ground has been historically significant. But what is far more important now is finding a common purpose. Because the pressing issue now for this region, as everywhere, should not be concerns of territory: the pressing issue is that our ecosystems are collapsing. There are far bigger things at play now.

Charlotte: So, it seems that the nature of this project could have broader appeal that makes it relevant elsewhere?

Emily: Yes, very much so. This area of the country is unique, but we would hope that the application of this kind of project is not. Many of the issues we are exploring and the messages we are conveying are universal, and a similar project could be applied to any water course. You could focus on a forest or mountain range in a similar manner.

But the wonderful thing about a river is that it is very visibly a system and its symbolic potential is huge. As a hydrological system it connects air to soil to vegetation – it connects mountains to forests and to the sea. It is essential for other life and physically impacts geology as well. Rivers can communicate our interconnectedness so immediately and beautifully, which is something we need to understand in the face of the challenges ahead.

Charlotte Maberly

More News & Views

Book Review: ‘The Serviceberry’

Martha Cass contemplates the message of a new book by Robin Wall Kimmerer that advocates ‘an economy of gifts and abundance’

Book Review: ‘Conversations with Dostoevsky’

Andrew Watson engages with an innovative new book by George Pattison which explores Dostoevsky’s relevance in the contemporary world

Thich Nhat Hanh & the Poetry of Engaged Buddhism

Philip Brown presents the poem ‘Recommendation’ and comments on the potential of contemplative art to foster compassion

Introducing… ‘Perfect Days’ and ‘Nowhere Special’

Jane Clark watches two films with a contemplative theme

Book Review: ‘Irreducible: Consciousness, Life, Computers and Human Nature’

Richard Gault reviews a new book by Federico Faggin, one of the leading lights of the science of consciousness

An Irish Atlantic Rainforest

Peter Mabey reviews a new book by Eoghan Daltun which presents an inspiring example of individual action in the face of climate change

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READERS’ COMMENTS

1 Comment

Submit a Comment

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

You’ve written terrific content on this topic, which goes to show how knowledgable you are on this subject. I happen to cover about Advertise on my personal blog UY6 and would appreciate some feedback. Thank you and keep posting good stuff!