News & Views

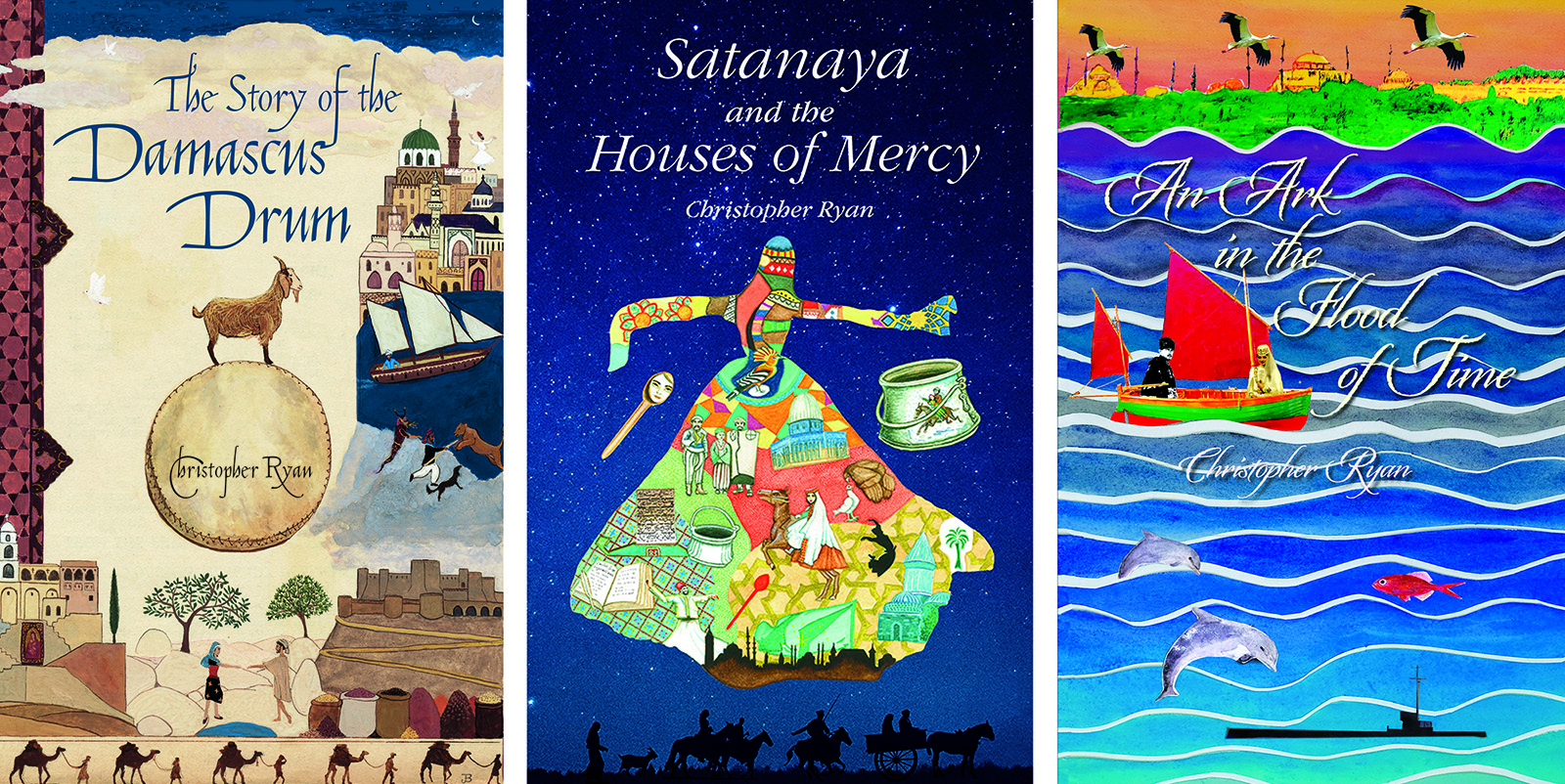

An Ark in the Flood of Time and other books by Christopher Ryan

Richard Gault reviews three epic tales from a master storyteller

Christopher Ryan outside the tomb of Mevlana Jalal al-din Rumi in Konya. Photograph: Francisca von Marx

Here are three wonderful books – books literally full of wonder – from the pen of a truly accomplished wordsmith. They are not quite a trilogy in the usual sense of the word, but all three share a setting, follow a chronological sequence and have characters who overlap. The first, The Story of the Damascus Drum,[1] is a ripping yarn; the second, Satanaya and the Houses of Mercy,[2] is a heart-warming, coming-of-age of tale; the third, An Ark in the Flood of Time (published in September 2021),[3] is an epic in which the stature of the human is magnified when set against the backdrop of a clash of civilisations

The author can properly be described as a man of the world. Born in Liverpool from Irish descent and raised in Australia, Christopher Ryan has travelled widely and enjoyed a rich variety of encounters in his journey through life. He has been a bus conductor, a builder, a credit analyst, a cook and a restaurateur. He has studied Persian and Ottoman Turkish, and has spent extended periods of time in Turkey and the Middle East. Hence he has a breadth and depth of experience to draw upon when he writes – and he does so effectively. Such an eclectic background makes it difficult to label him, but I will dare to describe him as a modern seanchaí.

Literally translated, the Irish Gaelic word seanchaí means ‘storyteller’. Now, calling Ryan a seanchaí is doing more than giving a nod to his Irish roots. Words carry cultural baggage. What storyteller means for somebody who is English is someone who tells stories – but a seanchaí is more than that. The seanchaí’s tales are transmissions of wisdoms – timeless wisdoms dressed in a form the contemporary audience can appreciate.

These books seem to me to be like the work of an artist whose palette is language and whose pen is his brush. Ryan does not paint with broad strokes, nor in the pixilated style of pointillism, but with the fine attention to detail of Vermeer. Like the Dutch master, he brings the worlds he portrays to life with a real warmth. Those worlds may be far from ours, separated from us by more than time and space, yet immersed in his books we inhabit them. For a while we cross the lands of the eastern Mediterranean of more than a century ago. We share the intimate lives of his characters, whose humanity is tangible and whose loves and losses we too endure.

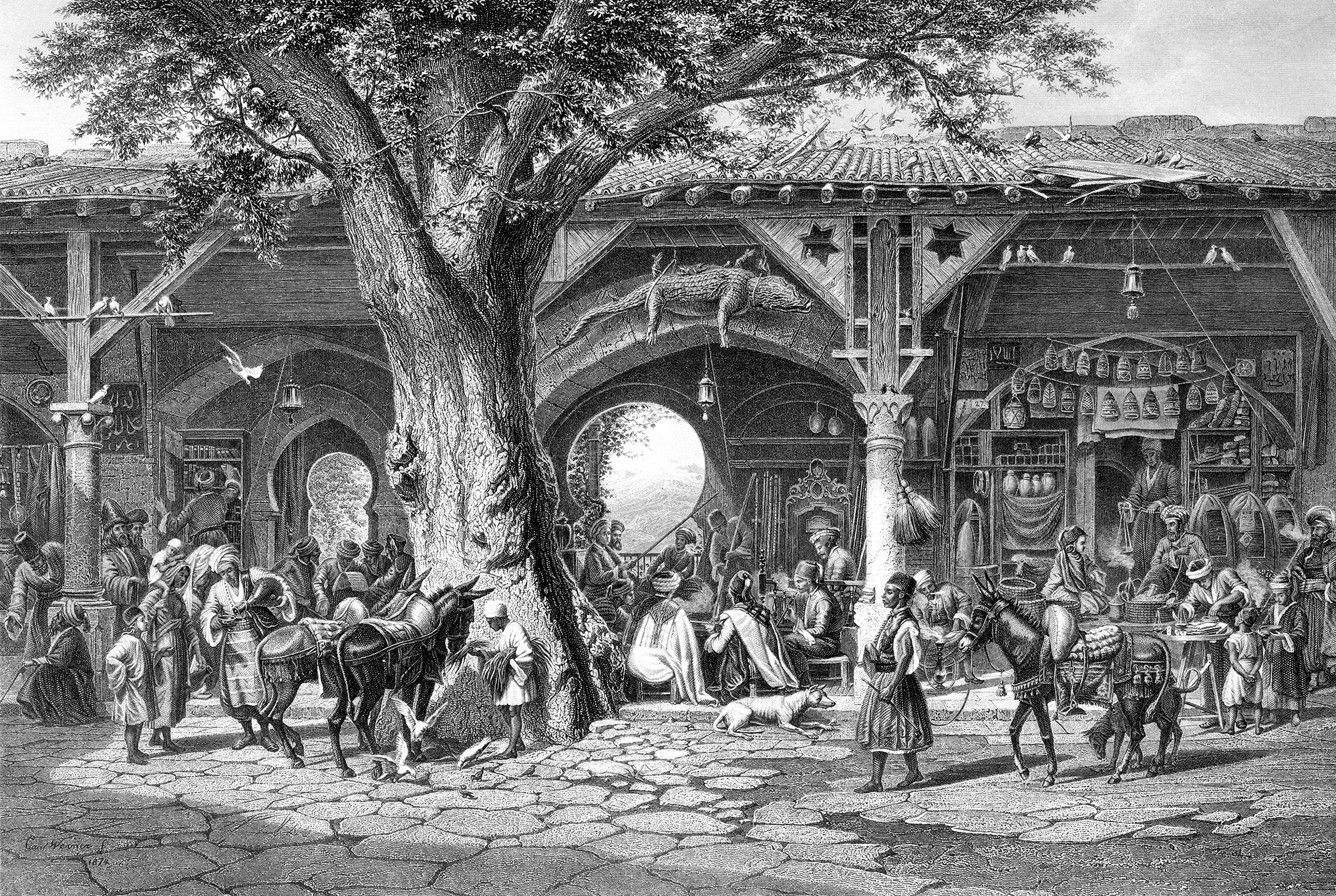

Engraving by Edward Whymper, from Picturesque Palestine, ed. Charles Wilson, 1881.

Move your computer mouse over the image to enlarge

The Story of the Damascus Drum

.

This is, as its title indicates, a story about a drum. But it is no ordinary drum. It is a drum which has a life of its own: a thinking, talking drum, inhabited by the spirit of the wonderful billy goat Shams, from whose hide it was made.

The words ‘once upon a time’ would give a clue that the book is a fairy story if they came at the start of the book. However, these are actually the very final words of The Story of the Damascus Drum. So it is not quite the conventional fairy story, although it shares many features of one. It is a rollicking tale of a battle between good and evil, a lone hero fighting bigger forces but aided by the certainty that ‘love conquers all’ (p.133). The story admittedly lacks a fairy but there are jinn; there is magic; there is love and there is a concluding (spoiler alert) ‘happily ever after’ life for the hero, Daud, and the heroine of the story, Takla.

The story is not set in some unnamed far-off kingdom but in Syria, which is still far away for most of us. No dates are given (after all, the truth of a fairy story is timeless) but clearly Daud and Takla are living in times past and we can deduce it is the late nineteenth century. What does the reader know of Syria a century and half ago? – probably very little when they picked up the book. By the time they put it down they will have become one of its citizens and been inducted into its culture, such is the evocative richness with which Ryan writes.

The Convent of Our Lady of Seydnaya, Syria. Photograph: Andrey Nekrasov [/] / Alamy Stock Photo

Satanaya and the Houses of Mercy

.

The Story of the Damascus Drum sets the scene for the opening of Ryan’s second book, but now the register is distinct. We are now firmly located in time and this is no fairy story but a novel. It describes the passage of the eponymous Satanaya as she moves from being a young pubescent girl into blossoming as a mature woman. The setting is again Syria, back in the Convent of Seydnaya in which Takla served – the first of the ‘houses of mercy’ Satanaya will encounter during the fifteen years of her life which the book spans.

Like Daud in Damascus Drum, Satanaya roams but she travels much further than he did. In this book Ryan takes us south to Jerusalem and north to Konya in Anatolia, and to many points in between. As we accompany Satanaya we encounter an astonishing variety of cultures, languages and religions. We will not get as far as the Caucasus from where her Circassian family had fled but we will learn much of Circassian history and way of life. If nothing else Ryan opens windows to peoples of whom most of us have barely, if ever, heard.

Satanaya’s tale is an engrossing one: an early life full of adventure. She suffers first love and first heartbreak; then more loves, more heartbreak; but each experience tempers her spirit. She is a young woman in search of herself, a journey which ends happily under the guidance of her teacher, Yeşil Efendi, in Konya. She is also a woman fulfilling her vocation – her destiny to be a cook. We witness her ever growing accomplishment, beginning with her early days in the kitchen of the convent where Takla had served before her. She learns that ‘the true cook […] discovers by taste …’ and that ‘the dish itself will teach the cook, for no other reason than its own love to be known …’ (p.55).

A standard advice for an aspiring writer is to write about what you know. Well, one thing Ryan certainly knows from his own life is cooking. His knowledge of and passion for the culinary art shines through all these books – but particularly this one. It is impossible to read of the dishes Satanaya prepares without one’s mouth watering. A single pilaf dish for a wedding feast is described as:

… delicately perfumed long grain rice from Hindustan, the fragrant basmati grown in the melt waters of the five rivers, the Punjab, first turned gently in much butter over a low heat then cooked in saffron-infused chicken stock, seasoned with cardamon seeds, with a suggestion of garam masala and rosewater, with pale sultanas and a colourful dice of petite pois, carrots, celery and onion, the whole dish to be showered with roasted flaked almonds and gold leaf… (p.220)

Ryan shows mercy for us by including a number of recipes for the dishes he so fulsomely describes in an appendix.

Satanaya is privileged to meet many helpers on her way. Amongst them is the remarkable Mother Superior. Her discourses on love are worthy of being a separate essay: ‘Love is soul’s food’, she begins (p.29), while concluding later with the aspiration to ‘drown … in Love’s ocean without a shore’ (p.223). The formidable Lady Gülbahar, Satanaya’s mentor, also advises her on love, explaining how the physical act should be seen as ‘beauty makes love to beauty’ (p.196) so ‘… that the true lover loves beauty itself, not simply the beautiful form, for the form will always pass…’ (p.295).

A dream vision inspires Satanaya to travel to Konya to pay homage to the great poet and mystic, Jalal al-din Rumi. Shortly before she leaves Syria she glimpses a young army officer named Mustafa. This is enough for her to recognise his ‘deeply hidden potential’ (p.247). At the very end of her time in Konya – when Yeşil Efendi has declared her ‘cooked’, and at a time of great upheaval in Turkey – Satanaya feels a new calling. She senses a summons from Constantinople. So we leave her travelling by very slow train to the then capital. Travelling slowly, unaware that the officer who had made such an intense impression on her was soon to be a focus of her life.

The Topkapi Palace in Istanbul, the residence of the Ottoman sultans until 1922. Photograph: Lebazele /iStock

An Ark in the Flood of Time

.

Satanaya’s story continues in the recently published third book of the series, An Ark in the Flood of Time, which differs again in character from the two earlier ones. This is not pure fiction but a ‘faction’, a non-fiction novel. The events within which the action takes place are historical. They cover the period from 1905 to 1922 which saw the final collapse of the Ottoman Empire, seven centuries after its creation, the horrors of the First World War and the subsequent fight for Turkish independence. Throughout this turbulent period the ‘hidden potential’ of the young officer Mustafa revealed itself. For Mustafa is Kemal Mustafa, the man who would adopt the name Atatürk and become the first leader of the Turkish Republic. An Ark in the Flood of Time describes the real history of this period as including an imagined relationship between Mustafa and Satanaya.

The novel offers extensive history lessons, for these opening decades of the twentieth century shaped the current map of the Balkans and the near East. Despite its continuing relevance, the story of this time and place is an unfamiliar one to most Europeans, known only in the sketchiest of form. By choosing to tell it through the medium of a novel, and by using his skill as a writer, Ryan enables us to vicariously experience the events of the time at the human level. Dry words can describe in outline form that there was a palace coup, a Sultan deposed, a Gallipoli campaign and so on, but they hide or even erase the displays of human virtues and vices behind them. Revolutions are not instigated by a group nor wars fought by countries: they are the doings of individuals.

Actually ‘turbulent’ inadequately describes the nature of this period in and around the disintegrating Ottoman empire. Vultures had long gathered about the deathbed of the ‘sick man of Europe’ in the forms of Russia, France, Italy, Germany and Britain, each vying with one another for a share of the corpse. The recently independent Balkan countries of Bulgaria and Serbia saw their own opportunities while also squabbling; Greece retained ambitions to make good the perceived wrong of 1453. Together this was a volatile mix making conflict inevitable – and not just from without. Discord within the ruling elite in Istanbul resulted in revolutions and assassinations. These internal divisions came at a heavy cost, often paid for by innocent populations, in particular the Armenians.

It is Ryan’s fictional creation – Satanaya’s father – who better names the period as ‘this flood of time’ (p.308). Sifting the flotsam from the jetsam and giving the time a coherence can have been no easy task, but it is one Ryan has not only achieved: he has succeeded in presenting it as a human drama. Albeit somewhat shorter, An Ark in the Flood of Time is War and Peace set a century later and a thousand miles further south.

Move your computer mouse over the image to enlarge

The Warp and The Weft of the Story

.

The tales that Ryan weaves are populated by intriguing and colourful characters who suffer loves and losses, display heroism and infamy – and even get to enjoy fine food and wine when the occasion permits. All this constitutes what we might see as the weft of his stories – but what of the warp?

All three books are woven around the wisdom that this seanchaí strives to convey. Ryan himself was very much influenced by a remarkable Turk, Bulent Rauf, himself an heir of the final years of the Ottoman Empire. Rauf was born into the aristocratic Ottoman elite of Constantinople and later in life was seminal in the establishment of the Beshara Trust, the Beshara School and the Muhyiddin Ibn ʿArabi Society in the UK. The knowledge that he passed on is the esoteric wisdom of, in particular, the Andalusian mystic, the ‘great shaykh’ Muhyiddin Ibn ʿArabi (1165–1240) and the Sufi poet Jalāl al-dīn Rūmī (1207–73).

To continue with the weaving metaphor, most of the stories are weft-faced, and the warp face is hidden, implicit not explicit. But sometimes the reader encounters a so-called ‘balanced weave’ where the warp is visible. An example of this is the account of Satanaya’s time in Konya, where she visits the tombs of saints and attends a Mevlevi ceremony. Another is when we learn that, although Daud ‘was not religious in the conventional sense’ (Drum, p.109), he finds help when he visits the tomb of Ibn ʿArabi in Damascus (op.cit., p.110).

There are some interesting passages where Satanaya questions the nature of religions. Why are there so many, she wonders, when exploring Jerusalem. The divisions are unsupportable, she concludes, because she grasps ‘that religions are bound by the spirit of a single substance.’ (Satanaya, p.148). Later she tries to explain her insight to Mustafa:

Religion is like a tree, where all the branches point in different directions. And the fruit of one branch imagines it is different and separate from the fruit on the branch opposite. But all the branches point upwards, and all the fruit falls to the earth. And when the tree dies, the fruit still carries the whole tree in its seeds. The whole tree. Don’t you see, the point is in the fruit, what it carries inside it. The whole tree hidden in the seed, the whole human potential in each person. (Ark, p.215)

So what is the religion of Ibn ʿArabi and Rumi? It is as described by the Mother Superior of Takla’s and Satanaya’s convent, ‘Our religion is the religion of love’ (Drum, p.205). Love, as we have noted, wends itself through all three books. ‘Only love can free the soul from the fears and iniquities of the world’, Satanaya’s father tells her (Ark, p.151). He elaborates:

The movement in the heart of existence, that origin in being from which we are all formed, and to which we ultimately return, is a movement of love. Our task here is to know and express this reality of the human being, each in his or her uniqueness, knowing that all stems from a single, absolute, undivided identity. (Ark, p.305)

This original premise was what Yeşil Efendi seeks to explain to Satanaya when, rhetorically, he asks her, ‘How many things are there in existence?’ He answers himself, ‘One! One only and unique aside from which there is nothing else’ (Satanaya, p.353). This is precisely what Rauf states to be ‘… the single most important point that must be understood by a person who wants to know’ [4] and is the doctrine of the ‘unity of being’ (wahdat al-wujûd) famously associated with Ibn ʿArabi. Hence, as her wise father concludes:

… there is only one thing to hold on to, when all else fails: the being, the existence, the one, God, love, beauty, whatever you want to call it, however it comes, by taste, by intellect, by a feeling or a movement in the heart, it is the human reality. You, Satanaya, be certain in that, it is your boat, your ark, in this flood of time. Only that will bring you to your destination. (Ark, p.308)

For anyone who already has some familiarity with the writings of Ibn ʿArabi, Rumi –or, indeed Rauf – reading Ryan’s books will evoke pleasures in addition to those his stories and writing style will undoubtedly bring. There will be sighs of recognition, welcome reminders, and possibly a deepening of understanding. For the previously unacquainted, new wisdom will be gained, interest perhaps stirred which in turn might lead to wanting to discover more. But all readers will surely come away from these books better for having read them – enchanted by the Drum, enlightened by Satanaya or inspired by the Ark.

All three books are published by Hakawati Press, and are available as an e-book or paperback from Amazon.

Dr Richard Gault has worked at universities in Scotland, Ireland, Holland and Germany, where he has taught and researched a variety of subjects, including the history and philosophy of science and technology

More News & Views

Don’t Take It Easy

Richard Gault is inspired by Michael Easter’s book The Comfort Crisis and explores the idea of ‘misogi’ during a 600-mile walk across Scotland

Book Review: ‘The Serviceberry’

Martha Cass contemplates the message of a new book by Robin Wall Kimmerer that advocates ‘an economy of gifts and abundance’

Book Review: ‘Conversations with Dostoevsky’

Andrew Watson engages with an innovative new book by George Pattison which explores Dostoevsky’s relevance in the contemporary world

Thich Nhat Hanh & the Poetry of Engaged Buddhism

Philip Brown presents the poem ‘Recommendation’ and comments on the potential of contemplative art to foster compassion

Introducing… ‘Perfect Days’ and ‘Nowhere Special’

Jane Clark watches two films with a contemplative theme

Book Review: ‘Irreducible: Consciousness, Life, Computers and Human Nature’

Richard Gault reviews a new book by Federico Faggin, one of the leading lights of the science of consciousness

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

Sources (click to open)

[1] CHRISTOPHER RYAN, The Story of the Damascus Drum (Hakawati Press, 2011).

[2] CHRISTOPHER RYAN, Satanaya and the Houses of Mercy (Hakawati Press, 2019).

[3] CHRISTOPHER RYAN, The Ark in the Flood of Time (Hakawati Press, 2021).

[4] BÜLENT RAUF, Addresses II (Beshara Publications, 2001), p.9.

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READERS’ COMMENTS

4 Comments

Submit a Comment

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

A most interesting and helpful review of all three books. Richard Gault paints a colourful picture of three thought provoking texts set in an area and culture I know little about. Now I’m hooked and will certainly be reading them soon.

As usual I am very impressed by your magazine. The quality is truly excellent. The book reviews are inviting me to read the books, and do so powerfully. I shall soon be acquiring them.

Thank you so much for your continued service to us.

Thank you George Wilson for your kind comments. The Beshara Magazine is run by volunteers and any support to develop the Magazine is most welcome through donation.

This was a lovely discovery – if I didn’t see know better I would say by chance – through the “Hippie Trail group on the FB. But I do know better than to believe in chance. Everything happens for a reason. Which exactly was it in this case I have yet to discover. But reading is my favourite activity and the three books described here sound very interesting. I asked somewhere whether they are available in the digital form. I have got the answer already. Thank you very much for a fascinating review .