News & Views

The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis by Amitav Ghosh

Christopher Ryan reviews an insightful book on climate change by the distinguished Bengali novelist

The fruit of the evergreen tree Myristica Fragrans which is cultivated for two spices: nutmeg, from its seed, and mace, from the outer seed covering. Photograph: കാക്കര via Wikimedia Commons

The fall of a lamp in the early 17th century, in the village of Selamon in a far-flung island archipelago of Banda in Indonesia, results in the wholesale destruction of a people and their way of life. With this ‘butterfly moment’, Amitav Ghosh raises the curtain upon a tale of perfidy and murder, revenge and war, conquests and defeats, riches, slavery, magic and sacrifice. A tragedy on a global scale. A world war spanning centuries, leaving no one unscathed.

It is a tale of humanity’s struggle with itself for the ever-elusive prize, at once of power and possessions – now dressed as spices, now as territories for grazing and agriculture, now as energy for industry and commerce to be extracted as timber, coal, oil and gas – only to discover that their adversary and the resistance to this urge, is ultimately ‘no other’ than itself. In fact Ghosh’s pen reveals that each slash of the conqueror’s blade – be it sword, plough or chainsaw, bulldozer or drill bit – generates a karmic response from its victim, the Earth, which retaliates with the destructive potential of what he calls ‘hidden forces’ through ‘climatic events of unprecedented and uncanny violence’. (p. 257)

But The Nutmeg’s Curse is no fiction. Ghosh is well known for revealing the darker side of British colonialism through the medium of the historical novel, notably in the Ibis Trilogy.[1] But here he presents us with the facts. Detailed in nineteen extensively annotated chapters, each replete with stories layered upon stories, he time-travels the reader back and forth across the globe, connecting information and diagnosing our current malaise, revealing an avaricious virus ever-mutating throughout our planet’s social history.

In some ways, the book is a summary of the prelude to the end of days – the great Armageddon that now awaits should this seemingly unstoppable juggernaut of destruction not become sated, stopped in its tracks and diverted. At the same time Ghosh proposes, if not exactly solutions, at least some alternative paths that humanity in the modern era has for the most part either bypassed, or simply out of unbridled desire to control the material of creation, blatantly refused to acknowledge, or actively attempted to block.

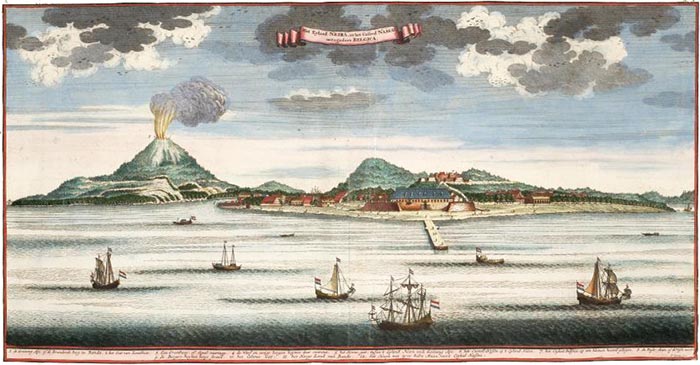

Banda Neira, one of the islands of the Banda archipelago, in ca.1724, when it was under Dutch rule. Photograph: Wikimedia Commons

The Parable of the Nutmeg

.

Ghosh has picked out some of the most relevant threads that have led us, and the planet in our train, to this predicament, namely: colonialism, and its adherents in slavery, terraforming, geo-engineering, and the current consequences of climate change and refugee crises. It is, he claims, the desire – the assumptive right – to control and possess what lies at the root of our misleading; a presumption based on an obsession with material power and the claim to superiority of the modern white European, who embodies a particular archetype to do with physical strength and mental cleverness.

The main threads, those hydra heads of desire which Ghosh highlights, begin for the modern era with the age of exploration. The ‘discovery’ of the ‘New World’ of the Americas, and the mapping of sea routes to Asia, with incidental ‘discoveries’ of Australasia and Oceania when the various European regions were bursting out of their backyards. This whetted the appetites of numerous adventurers and risk capitalists of Spain, The Netherlands and England in particular. In the wake of these conquistadors and traders came extermination by stealth, as imported European diseases decimated the indigenous populations of the Americas, Australia, the Pacific Islands and elsewhere.

Thus piratical colonialism mutated into capitalism. From simple trading links with local populations, on the principle of ‘superior subjugating the inferior’, came slavery, genocide and extermination, of ‘other’ humans and animals and the subsequent grabbing of the now emptied-out lands. This was social engineering aimed at providing maximum power and possession to the ‘superior’ and forceful, and out of it grew the empires of the late 19th and 20th centuries. The ‘Great War’ which saw the collapse of these forms, ushered in the next generation of empires which we see today, based on possessing the new energy resources that power modern global industrialisation.

The story of the nutmeg, which until the 17th century was found only on the islands of Banda, weaves in and out of his exposition. Greedy for this highly prized ‘commodity’, the island was colonised by the Dutch, who evicted and enslaved the entire population in order to create a global trade monopoly. But when the plantations ceased to be profitable, they set about destroying the very trees on which their fortune had been built. Fortunately, the nutmeg refused to be eradicated, taking refuge in the inaccessible highlands. But now, in the 21st century, the trees are dying because climate change is destroying the delicate balance of the island’s ecosystem.

For Ghosh, the fate of the nutmeg is a parable – that is, a story which demonstrates a spiritual truth. It encapsulates, on one hand, the whole sorry tale of colonisation, and on another, it serves to illustrate the more poetic theme of the book, which is the way in which non-human agents intertwine, and have always intertwined, with humanity’s affairs.

Amazonian indigenous leaders (left to right) Dario Vitorio Kopenawa Yanomami, Davi Kopenawa Yanomami, Raoni Metuktire, and Megaron Txucarramae deliver a letter to 10 Downing Street, London, calling on Prime Minister Boris Johnson to condemn the actions of Brazil’s president Jair Bolsonaro in failing to protect indigenous tribes in the Amazon rainforest. Photograph: Dominic Lipinski/Alamy Stock Photo

The Contemporary World

.

In case one imagines, as one staggers beneath the avalanche of injustices that Ghosh catalogues, that this book is simply a polemic against the evil beast of historic colonialism, one brief quote had me fact checking a source via Google. Ghosh extracts from Fiona Watson’s reporting of Brazil’s President Bolsonaro the sentence: ‘It’s a shame that the Brazilian cavalry hasn’t been as efficient as the Americans who exterminated the Indians’. (p. 213) Reading the whole article,[2] one cannot but be shocked and revolted at the foul intent of this unreconstructed Nazi. Ghosh comments:

“Where Bolsonaro is right is that a large part of Brazil has so far escaped the fate of the interior of North America: it has not yet been terraformed into a neo-Europe like, say, the American Mid-west. But this is exactly what Bolsonaro’s government intends to change; the goal is to complete the project of colonial terraforming by replacing vast swathes of the rain forest with cattle ranches, mines, and soya and sugarcane monocultures.” (p. 213)

But it is not all doom and gloom. Ghosh throws us various lifelines of hope. For example in the chapter on ‘Monstrous Gaia’, he embraces the scientific hypothesis developed by James Lovelock and Lynn Margolis which sees the earth not as inert and passive, but as a living, vital entity. Echoing the 17th-century clergyman Thomas Traherne (see our article) he writes: ‘The planet will never come alive for you unless your songs and stories give life to all beings, seen and unseen, that inhabit a living Earth – Gaia.’ (p. 84) He relates how since pre-history humankind has invested all the denizens of this home of Earth – whether animal or plant, tree or mountain – with powers of speech and action which may manifest either directly through their individual forms, or more globally through seismological events such as volcanoes and earthquakes, or violent and unforeseen weather phenomena.

Things which modern people relegate to the realm of myth, therefore fantasy and imagination, Ghosh proposes are subtle realities which are visible or audible only to the sensibilities of those societies still in close communion with their origins. Ultimately connected in Gaia, these expressions, through which Gaia herself communicates in an analytical sense, are synthesised in the human emergence. In Indonesia, he tells us a volcano may be seen as:

… a spiritual as well as a geothermal entity – a vengeful and angry geospirit… Javanese people often share a deeply devout relationship with volcanoes… [they] are considered connected to human society to achieve a universal harmony between society, nature, and the cosmos. (p. 33)

Yet the choices of modern humanity have taken us on a path that has ruptured the harmony of our intended destination – a consonant, even paradisiacal existence on earth – and brought about a disconnect with the common source.

Another lifeline of hope is the extraordinary persistence of indigenous people, who, like the nutmeg trees of Banda, have refused to let either themselves, or the knowledge they hold, be entirely eliminated. Ghosh cites modern spokesmen like Davi Kopenawa, from the Yanomani tribe in Brazil’s Amazonas province,[3] or the North American author and activist Winona LaDuke,[4] who, he says ‘have stubbornly continued to insist, in the face of unrelenting, apocalyptic violence, that non-humans can, do and must speak.’ (p. 257) He similarly sees hope in the activism of environmental groups around the world, who through legal actions and popular campaigns are managing to successfully challenge threats to our remaining natural heritage.

Greta Thunberg, the young Swedish activist, in August 2018, outside the Swedish parliament building, inititiating a global wave of school strikes to raise awareness of the climate crisis. Photograph: Anders Hellberg via Wikimedia Commons

Ways Forward

.

Ghosh’s book certainly has the power to shock, as the pendulum of his argument swings between outrageous examples of the colonisers’ glorification of materialism and white supremacy, and the depressing consequences of the genocide of indigenous tribes and the wholesale destruction of their natural support systems in terms of game for food, the forests and the prairies. It becomes hard not to entertain the idea of a karmic connection between all this and the Covid-19 pandemic. Ghosh wrote The Nutmeg’s Curse whilst he was living in New York in March 2020, and he muses on this connection when he refers to ‘an uncanny intersection between human and non-human forms of agency’. He connects in his mind ‘the sirens of speeding ambulances’ and the nearby hospital in Brooklyn where ‘the bodies of the dead were being stacked outside, in refrigerated trucks’ with ‘a sense of kinship with the terror-struck villagers of Selamon… wondering if the fall of the lamp was a portent of worse things to come.’ (p. 15)

It has been said that the current stage in human evolution will divide humankind between those who know – including those who want to know, and are willing to be educated – in confrontation with those who do not want to know. What is being referred to here is esoteric knowledge. There is much in The Nutmeg’s Curse that might contribute towards this evolution. In the penultimate chapter, for instance, Ghosh goes some way to suggest that no solution is possible without the willing participation of the majority of the world’s population, and hence the necessity to find ‘a common idiom and a shared story’ which he calls ‘a narrative of humility in which humans acknowledge their mutual dependence not just on each other, but on “all our relatives”’. (p. 242)

He admits that ‘such a narrative would… require a seismic shift in consciousness for those who remain wedded to the conception that humans are the only ensouled beings’. (pp. 242–3) But whilst he sanctions a kind of pantheistic union of interconnectivity, he appears to stop short of supporting the sort of unity of consciousness that some physicists and philosophers which have featured in Beshara Magazine, such as Federico Faggin [5] or Bernardo Kastrup,[6] are now proposing. Perhaps colloquia of such important minds would provide fertile ground for a deeper appreciation of these crucial considerations we so urgently need to unpick.

This is an important and thought-provoking book, and the danger is that it will be read only by the already-converted. Really, it should be in the syllabus of our schools’ social history classes from the age of fourteen or even younger, alongside the words of Greta Thunberg and David Attenborough and such prophetic lyrics as those of Nobel Prize winning songster Bob Dylan:

I heard the sound of a thunder, it roared out a warnin’

Heard the roar of a wave that could drown the whole world

Heard one hundred drummers whose hands were a-blazin’

Heard ten thousand whisperin’ and nobody listenin’… [7]

The dishes on Ghosh’s table are rich and varied. Whether bitter or sweet, they need to be debated and argued, dissected and digested by the generation that is going to have to deal with the consequences of the current human crisis and shift its current trajectory, which, with the best will in the world, appears to be leading us to hell in a handcart. So let’s give it to our children and grandchildren, make them read it, and bribe them if necessary! Their future may depend on it.

Grated nutmeg. Photograph: seanrmcdermid/iStock

After Thought

.

While writing this review, I came upon a couple of nutmeg kernels obtained twenty years ago in Indonesia. I kept them there, in sight on my desk as talismans to remind and connect me to their origin. Later I grated a little of one into a béchamel I was making. The scent released was fragrant, fresh and strong, undiminished in its waiting.

The curse of the nutmeg, this scent both bitter and sweet, redolent in the kernel long after its removal from its origin, is like the sin that time does not expunge, but remains, a hidden wound that never heals, the damned spot that will not out, until it is exposed, by painful grating, then seen, admitted and dealt with. While all may be forgiven in the final analysis, in the great return that is death – the real awakening – it would be better surely to deal with in the here and now, to benefit in full in the release of a knowledge which would allow further, and mutually beneficial, steps of development to occur in the world soul. So, even after the tree has fallen, the scent remains as a haunting witness, as a curse that could be transformed into a blessing.

The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis by Amitav Ghosh was published by John Murray (London) in 2021.

The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis by Amitav Ghosh was published by John Murray (London) in 2021.

Christopher Ryan is a cook and writer who lives in Scotland For a review of his latest novel, An Ark in the Flood of Time, and other works, click here.

More News & Views

Don’t Take It Easy

Richard Gault is inspired by Michael Easter’s book The Comfort Crisis and explores the idea of ‘misogi’ during a 600-mile walk across Scotland

Book Review: ‘The Serviceberry’

Martha Cass contemplates the message of a new book by Robin Wall Kimmerer that advocates ‘an economy of gifts and abundance’

Book Review: ‘Conversations with Dostoevsky’

Andrew Watson engages with an innovative new book by George Pattison which explores Dostoevsky’s relevance in the contemporary world

Thich Nhat Hanh & the Poetry of Engaged Buddhism

Philip Brown presents the poem ‘Recommendation’ and comments on the potential of contemplative art to foster compassion

Introducing… ‘Perfect Days’ and ‘Nowhere Special’

Jane Clark watches two films with a contemplative theme

Book Review: ‘Irreducible: Consciousness, Life, Computers and Human Nature’

Richard Gault reviews a new book by Federico Faggin, one of the leading lights of the science of consciousness

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

Sources (click to open)

[1] AMITAV GHOSH: The Ibis Trilogy

Sea of Poppies (Farrar Straus Giroud, 2008)

River of Smoke (Penguin, 2011)

Flood of Fire (John Murray, 2015)

[2] FIONA WATSON, ‘Bolsonaro’s election is catastrophic news for Brazil’s indigenous tribes’; https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/oct/31/jair-bolsonaro-brazil-indigenous-tribes-mining-logging

[3] DAVI KOPENAWA, The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman (Harvard University Press, 2013).

[4] WINONA LADUKE, Recovering the Sacred: The Power of Naming and Claiming (Haymarket Books, 2016).

[5] FEDERICO FAGGIN: ‘Consciousness as the Ground of Being’, an interview with Jane Clark and Richard Gault, https://besharamagazine.org/science-technology/consciousness-as-the-ground-of-being/

See also a review of his autobiography Silicon (Waterside Productions, 2021) by Richard Gault: https://besharamagazine.org/newsandviews/silicon-by-federico-faggin/

[6] BERNARDO KASTRUP: ‘Mind over Matter’, an interview with Jane Clark and Richard Gault: https://besharamagazine.org/science-technology/mind-over-matter/

[7] BOB DYLAN, ‘A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall’ from the album The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963).

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READERS’ COMMENTS

4 Comments

Submit a Comment

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

This is a skillful and wise review, as can be expected from Christopher.

towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The

origin. Later I grated a little of one into a béchamel I was making. The scent released was fragrant, fresh and strong, undiminished in its waiting.