News & Views

A West-Eastern Divan for Our Time

Robin Thomson comments upon events marking Goethe’s ground-breaking tribute to the great Persian poet, Hafiz

The Hafiz Goethe Memorial at Beethovenplatz in Weimar, commemorating the meeting of minds of the two great poets. Photograph © Henry Sowinski, Genius Loci Weimar 2016

On a recent visit to Weimar, Germany, I stumbled on an exhibition dedicated to the poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s West-Eastern Divan, marking 200 years since its publication in 1819. [1] Goethe was in his mid-sixties when his long-standing publisher and friend, Johann Friedrich Cotta, gave him a new German translation of the Divan of the 14th-century Persian poet Hafiz [/]. Having had an interest in orientalism for many years, Hafiz’ imagery and allusions fell on fertile soil; far from being merely a pleasant encounter with familiar ideas, it was a pivotal moment for Goethe. He experienced what he himself described as a ‘second puberty’, the sense of creative stagnation that he had endured in his latter years blown away by a wave of new poems of his own – a good hundred of them sketched or completed in a single year around 1815 – inspired by the Persian verses.

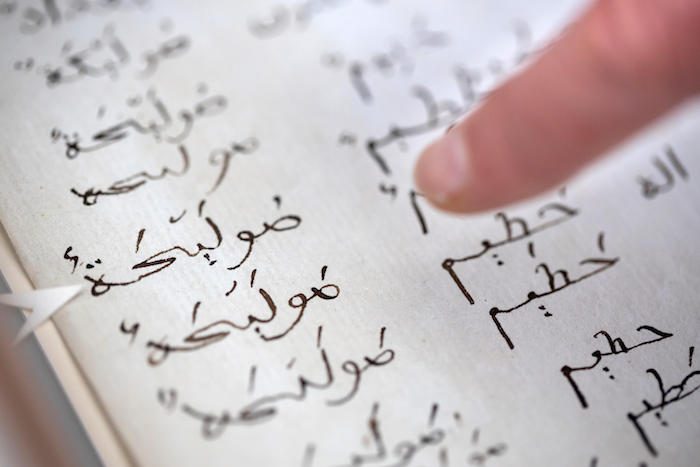

Here at the Weimar exhibition were pages of Goethe’s manuscripts, including title pages and halting reproductions of lines of Persian and Arabic (of which he had made efforts to learn the script). As the individual poems mounted up, Goethe organised them into a ‘German Divan’ as a response to Hafiz, whom he addressed in some of the poems as his twin. Having heard a call of awakening from the East, he replied from the West, and the result was a bridge of poetry and of ideas. He wrote:

Know yourself and in that instant

Know the Other and see therefore

Orient and Occident

Cannot be parted for evermore

In the course of writing the poems, the ageing Goethe also fell in love with Marianne von Willemer, the young wife of a Frankfurt banker (who seems to have tolerated the entanglement for poetry’s sake!). This affair further fired his project: direct experience of love, for itself and to energise his reply to the love-drenched ghazals of Hafiz. The poems resulting from their union (some of them written by von Willemer) became the ‘Book of Suleika’ at the heart of the West-Eastern Divan, with Goethe taking on the persona of ‘Hatem’ to address his lover in a poetic re-enactment of the great Persian epic ‘Joseph and Zuleika’ [/].

Goethe’s exercises in Arabic script, spelling out the words ‘Haṭīm’ and ‘Ṣulaikha’. From the Goethe and Schiller Archive, as shown in the exhibition ‘Poetic Pearls – 200 years of Goethe’s West-Eastern Divan’ in Weimar, April to July 2019. Photograph: Michael Reichel/dpa/Alamy Stock Photo.

A New Divan for Our Time

.

The bicentenary has been marked by the publication of two new books by Gingko [/] – an organisation dedicated to East-West dialogue, whose name is itself a reference to Goethe’s Divan (see below). The first is a new bi-lingual edition of the original West-Eastern Divan with a prose translation into English by the distinguished scholar Eric Ormbsy. [2] Including unpublished poems plus Goethe’s own ‘Notes and Essays…’, this also highlights the work’s great influence upon literary development in its time, which was, Ormsby states in the introduction, “nothing less than a decisive reconfiguration of German, and indeed European, poetry”.

The second is A New Divan [/], subtitled, A Lyrical Dialogue between East and West. [3] In this, twelve modern poets of the East address the West and twelve of the West address the East in the Goethean spirit. The poets come from across the East (from Morocco to Turkey, Syria to Afghanistan) and from across the West (from Germany to Mexico, Estonia to Brazil). Each has responded to a title of one of the twelve ‘books’ of Goethe’s original work, including ‘The Poet’, ‘Love’, ‘Ill-humour’, ‘The Tyrant’ and ‘Paradise’. Twenty-two English-language poets have created English versions of the translations. Contributors include Adonis, Mourid Barghouti, Elaine Feinstein, Jan Wagner, Don Paterson and Paul Farley. The venture has been marked by live readings and performances across the UK and Germany (click here for forthcoming venues. [/])

To give a taste, here is an extract from the poem ‘Aubade’ by the Moroccan poet Mohammed Bennis, under the theme ‘The Cup-bearer’.

In this time of hardship, truth bickered over by despots,

with the water of love shall I wash the soul

clean of all profanity

So welcome, glass of ruby-jewelled wine!

From this glass will I drink in praise of love

night after night will I faithfully strive

to praise those amongst the host of poets

who sang for the land – as it once was and ever shall be –

the poets’ mother country

I, the drunk –

I see the wondrous unknown shining

on a silence that cocks its head and beckons

In the spaces between us, infinity opens

This my faith, this my happiness [4]

And the first of section of ‘The Obedience of Water’ by the Palestinian poet, Mourid Barghouti (‘Tyrants’ section):

How many nights of art, close study, hesitation and sacrifice,

at little or great expense, do you need to invent

the simplest of gadgets?

All you need to invent a tyrant is a single

bend of the knee. [5]

Some of the contributors to A New Divan at the Edinburgh Festival in August. From left to right: Sean O’Brien, Gilles Ortlieb, Barbara Schwepcke, Jo Shapcott, Narguess Farzad, Robin Robertson, Bill Swainson

This is not the first reinvention of the Divan; twenty years ago (another anniversary) and also in Weimar, the Israeli musician Daniel Barenboim and the Palestinian writer Edward Said formed the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra [/] with the purpose of bringing young Jewish and Arab musicians together to play music, to build up to a professional standard – and to talk to one another. The orchestra recently appeared in the 2019 BBC Proms with a programme of Tchaikovsky, Schubert and Lutoslawski to great reception.

Said is of course, famous for his book Orientialism [/] [4] which argued that much East-West scholarship and dialogue is a covert form of Western imperialism. But he did not see Goethe’s Divan in this light; Marina Warner, whose book Stranger Magic contains a chapter on the Divan, [6] explained in a recent BBC progamme that Said rather saw Goethe as “opening up a dialogue which allowed the thought that he encountered to enter him, rather than it being a process of acquisition”. [7] (to listen to the podcast of this, click here… [/]) The link between the two projects is further underlined by the introductions to A New Divan, which are written by Barrrenboim and Said’s widow, Mariam.

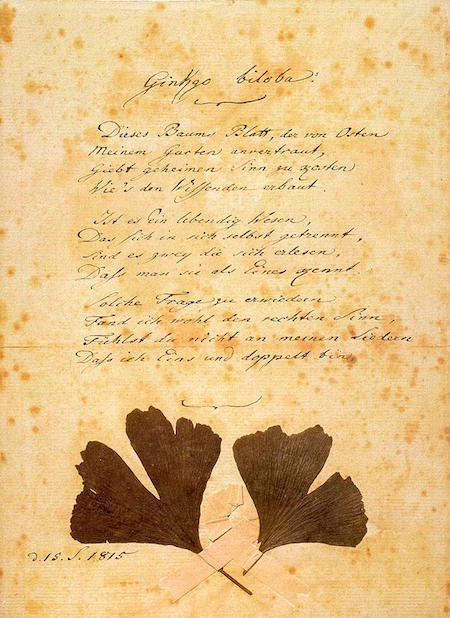

A page from the original West-Eastern Divan, containing the poem ‘Gingko Biloba’, addressed to Marianne von Willemer. For a translation, see below.

Meanings

.

So what was Goethe’s purpose in writing his German Divan? Was it just a response at the aesthetic level to the rich imagery and poetic devices of the East, likely heightened by a romanticised view of the Orient? Or was it an attempt, perhaps foreshadowing the geopolitics of our own times, to reconcile an East and a West so often at odds? Or did Goethe also sense Hafiz’ purpose on a higher level, given that Persian poetry of this type, when read for its highest meaning, speaks of the beauty of the Divine Beloved, God, and was excused by the religious orthodoxy for using even quite licentious imagery to that end?

After a recent event at the Edinburgh Book Festival which presented live readings from the New Divan, Narguess Farzad, senior fellow in Persian at SOAS and a contributor to the book, gave me a categorical answer to this last question. Hafiz – whom she could quote freely in a gorgeous liquid Persian – combined heavenly and earthly concerns quite tightly in his poetry and maintained a sobriety and attention to craftsmanship that contrasted with the more ecstatic work of, say, Jalaluddin Rumi. Nevertheless, Hafiz’ real concern was equally with beauty, and through beauty, love: and his point was that the only effective and reliable route to the Divine is through these two principles. Goethe would surely have understood this, Farzad maintains; his earlier Oriental studies would have alerted him to the mystical dimensions of Persian poetry, but also, his own reception of the message of beauty and love in Hafiz is clear and evident from the scope and enduring quality of his poetic response.

In his work Goethe aspired to Weltliteratur or world literature. In his West-Eastern Divan he also addresses poetry itself, as a being in its own right – as something that can roam heaven and earth and link people from faraway places and across time, each referencing the other. His aim was to give Western readers access to what he called the ‘ungeheurer Stoff’ – the tremendous or immense ‘stuff’ or ‘substance’ – of the ‘East’. The New Divan with its diversity of authors and source countries takes this a stage further at a time of great trouble between East and West, seeking to access that immensity or reality through encounter in sound and language, at once distinct and universal.

Gingko Biloba |

|

|

Dieses Baum’s Blatt, der von Osten |

The leaf of this tree, that from the East has been entrusted to my garden, gives a secret meaning to savour as it gladdens those who know. |

|

Ist es Ein lebendig Wesen? |

Is it One being that divides itself within itself? Is it two that have chosen each other so as to be seen as One? |

|

Solche Fragen zu erwiedern |

To answer such questions I have discovered the correct sense: do you not feel that in my songs I am both double and One?

|

|

|

From the West-Eastern Divan, translated by Eric Ormsby

|

More News & Views

Don’t Take It Easy

Richard Gault is inspired by Michael Easter’s book The Comfort Crisis and explores the idea of ‘misogi’ during a 600-mile walk across Scotland

Book Review: ‘The Serviceberry’

Martha Cass contemplates the message of a new book by Robin Wall Kimmerer that advocates ‘an economy of gifts and abundance’

Book Review: ‘Conversations with Dostoevsky’

Andrew Watson engages with an innovative new book by George Pattison which explores Dostoevsky’s relevance in the contemporary world

Thich Nhat Hanh & the Poetry of Engaged Buddhism

Philip Brown presents the poem ‘Recommendation’ and comments on the potential of contemplative art to foster compassion

Introducing… ‘Perfect Days’ and ‘Nowhere Special’

Jane Clark watches two films with a contemplative theme

Book Review: ‘Irreducible: Consciousness, Life, Computers and Human Nature’

Richard Gault reviews a new book by Federico Faggin, one of the leading lights of the science of consciousness

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

Sources (click to open)

1) ‘“Poetic Pearls”’ from the “Tremendous Stuff” of the Orient’, Klassik Stiftung Weimar, 10th April to 21st July 2019.

2) Goethe, West-Eastern Divan, translated by Eric Ormsby (Gingko Library, 2019)

3) A New Divan: A Lyrical Dialogue Between East and West, eds. Bill Swainson and Barbara Schwepcke (Gingko Library, 2019)

4) From ‘Aubade’ by Mohammed Bennis, A New Divan, p. 75. English version by Sinéad Morrissey based on the literal translation from the Arabic by Mbarek Sryfi.

5) From ‘The Obedience of Water’ by Mourid Barghouti, A New Divan, p. 59. English version by George Szirtes based on the literal translation from the Arabic by Khaled Aljbailli.

6) Edward W Said, Orientalism (Penguin 25th Anniversary edition, 2003)

7) Marina Warner, Stranger Magic: Charmed States & Arabian Nights (Vintage, 2012)

8) From a BBC programme ‘Goethe and the West-Eastern Divan’ with Paul Farley, 21st July 2012. Click here for the podcast.

Robin Thomson is a translator and traveller who lives in the Scottish Borders.

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READERS’ COMMENTS

1 Comment

Submit a Comment

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

Hey, I enjoyed reading your posts! You have great ideas. Are you looking to get resources about Cosmetics or some new insights? If so, check out my website 67U