Metaphysics & Spirituality _|_ Issue 23, 2023

The Matter with Things

Dr Iain McGilchrist discusses his most recent book which brings together neuroscience, psychology and philosophy into a unified vision

The Matter with Things

Dr Iain McGilchrist discusses his most recent book which brings together neuroscience, psychology and philosophy into a unified vision

Iain McGilchrist is psychiatrist, neurologist, philosopher and writer whose seminal work, The Master and His Emissary (2009) presented the notion that the two hemispheres of the human brain approach the world in two very different ways. He argues passionately for the importance – often overlooked in the modern world – of the right hemisphere, which sees the world as a unified, living process. In his most recent book, The Matter with Things (2021) (see our review) he further explores the philosophical implications of this idea. The book is a magnus opus of some 1,500 pages which amounts to a very strong argument, supported by an extraordinary range of evidence, for a unified view of the cosmos. He talked to Richard Gault and Jane Clark by Zoom from his home on Skye.

Richard: The Matter with Things [1] would probably be classified as science and/or philosophy, but you actually started out studying English literature at University of Oxford. Then after obtaining a fellowship there, you suddenly switched to medicine. From the outside, that looks like a remarkable thing to do – although I have learned from your film The Divided Brain [/] that you were following in your father’s footsteps, because he too switched from an academic discipline to become a doctor.

Richard: The Matter with Things [1] would probably be classified as science and/or philosophy, but you actually started out studying English literature at University of Oxford. Then after obtaining a fellowship there, you suddenly switched to medicine. From the outside, that looks like a remarkable thing to do – although I have learned from your film The Divided Brain [/] that you were following in your father’s footsteps, because he too switched from an academic discipline to become a doctor.

Iain: Well, it wasn’t quite as sudden as it appears. I have always mainly been interested in philosophy. I wanted to read it at Oxford, but I didn’t want to do P.P.E., which is their flagship degree in which you study philosophy, politics and economics. I hadn’t the slightest interest in politics or economics, but they had luckily just started a degree called philosophy and theology, and I was interested in the kind of philosophy that has room for theology rather than economics.

But you had to sit an entrance exam to Oxford in those days, and it had to be in a school subject. Neither theology nor philosophy were taught at school, so I chose English – I could say ‘at random’, but it wasn’t quite; it was a subject I was studying at the time. My interviewers were John Bayley, an English critic from whom I learnt a very great deal – he is more often known as the husband of Iris Murdoch but he was a great writer in his own right – and Christopher Tolkien, son of J.R. Tolkien, the author of Lord of the Rings, who taught me Anglo-Saxon. They said: ‘You can’t do theology and philosophy as it is not an honours degree. Come and do English.’ So I did.

Then, almost immediately after my finals, I got a fellowship at All Souls College in Oxford. This enabled me to do exactly what I wanted, intellectually speaking, for seven years, no questions asked. I did some teaching, but I wasn’t encouraged to teach; I was encouraged to go where my wits wanted me to, which was wonderful. I don’t think this kind of fellowship exists in quite the same form now, but it was a visionary thing that enabled me to broaden my horizon enormously, especially into science and other languages. I found myself a Russian teacher, and started studying a lot of psychology and philosophy. The result was that I wrote a book called Against Criticism,[2] which was published by Faber and I believe was unceremoniously remaindered after selling about 400 copies.

Jane: And the central argument of this was…?

Iain: That a work of art such as a poem is entirely unique, embodied and contextual. But what you do in the seminar room is make it disembodied and decontextualized; and you turn the unique into the general by paraphrasing it and making explicit what should be – and must always remain – implicit. But a work of art falls apart when you make it explicit. Telling somebody what a poem ‘means’ is a way of destroying it, rather like explaining a joke.

As I was trying to find a way of talking about this in Against Criticism, I had the thought: this is all about the mind-body problem. This led me to attend philosophy seminars on the subject, but I found them to be all just too disembodied and I felt I needed to look at the matter in a more embodied way. And that embodied way was medicine, then neurology and psychiatry – looking at the borderline between neurology and psychiatry, where the brain and the mind overlap.

So that’s how it all happened. I was very influenced by Oliver Sacks, who had published Awakenings [3] in 1973. I thought that was a wonderful book and I wanted to be something like him, I suppose.

The Maze by William Kurelek (1953) painted whilst he was a patient at the Maudesley Hospital in London. McGilchrist regards it is as ‘almost unparalleled for its portrayal of the mental world of schizophrenia’. (The Matter with Things, p. 430 xi). Image: Wikimedia Commons.

Move your computer mouse over the image in order to enlarge

The Two Hemispheres of the Brain

.

Richard: When did you first get a glimpse of the thesis that you brought out in The Master and His Emissary [4] about the two hemispheres of the brain?

Iain: One day in about 1990 I saw an advertisement on a noticeboard in the corridor in the Maudsley Hospital after I’d only been there about a year, advertising a lecture by somebody I’d never heard of – John Cutting – who later became a friend, a colleague, and an enormous influence on me. The lecture was called ‘The Right Cerebral Hemisphere and Psychiatric Disorders’,[5] which was also the name of a book that he had just published with Oxford University Press. I thought this was fascinating because during my training as a neurologist I’d heard almost nothing about the right hemisphere – almost everything seemed to be done by the left side of the brain. There was almost a sense that the right hemisphere was there just to prop up the left and stop it falling over, but it didn’t really do anything very much in its own right.

Nevertheless, I’d already had some tantalising glimpses that things were more complex. For example, the fact that the corpus callosum – the band of fibres that connects the two hemispheres – is largely inhibitory in its function. That alone sat in my mind for a while, germinating as something interesting; later I realised that the two hemispheres must be – in fact fairly obviously are – asymmetrical. I thought, well, why is the brain divided at all? After all, if its purpose is to make connections and that’s where its power originates, why on earth would it have evolved to be divided? What I didn’t know then was that it had not only evolved to be divided, but that the corpus callosum is getting smaller in relation to the size of the brain, not larger, with evolution, and also is becoming more inhibitory.

So I went to the lecture, and to cut a long story short, I had a eureka moment. I have always struggled with writing and all three of my major books have been a colossal struggle. Against Criticism was really difficult because I was trying to explain by using the sort of terminology I was familiar with – analytic terminology – why it is important that something remains implicit. Why is it so important not to take things apart in order to understand what they are? – to recognise that a piece of writing has a kind of uniqueness? In that hour’s lecture, amongst various things, I heard from John Cutting that the right hemisphere alone sees uniqueness. The left hemisphere sees everything as an instance of a category, whereas the right hemisphere is much more interested in context and embodiment. It’s more in touch, literally, with the functioning of the body than the left hemisphere.

The other thing that I learnt is that the right hemisphere also understands implicit meaning – metaphors, jokes, irony, sarcasm, humour – all the stuff that isn’t explicitly said. But it hasn’t got a voice. While it’s not true that language is just processed in the left hemisphere – in fact it’s processed in both in different ways – speech for almost all right-handed people is firmly in the left hemisphere. So articulating these meanings is very, very difficult. After the lecture I went up to John Cutting and said: ‘That was utterly fascinating, and actually I wrote a book that’s rather relevant to this’. And he said, ‘Well, can I read it?’ And he did. The result was that he invited me to join in his research, and that set me off on a track which led me to Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore (which is a big research centre in neuroscience), where I looked at abnormalities of asymmetry in the brains of people with schizophrenia.

Richard: Can you summarise what you discovered in the course of this research?

Iain: Well, the normal brain is asymmetrical in a completely predictable way. But in schizophrenia, one of the things that has been noticed is that people’s brains are either symmetrical or have reversed asymmetry in terms of the parts that should be enlarged; so if the left would normally be enlarged, then the right would be, and vice versa. And these areas just happen to be to do with the areas in which people with schizophrenia find difficulty: reality testing, empathy, language formation and so forth.

I was well into that when I got an excited letter from John Cutting about a book by the American psychologist Louis Sass, called Madness and Modernism: Insanity in the Light of Modern Art, Literature and Thought,[6] which had just come out in 1992. What Sass shows in this beautifully written and researched book is that the history of psychology reveals that over time we are beginning to exemplify in our art and in our thinking many of the phenomena that are described by subjects with schizophrenia. He makes some 25, possibly more, parallels between the phenomenology of someone with schizophrenia– the things they say, the things they do, the things they see – and what has developed over 100 years of modernism.

It is an absolutely extraordinary piece of work. Of course, I realised at once that the explanation could not be that we are all developing schizophrenia. But what I had noted already is that one of the problems in schizophrenia is that the right hemisphere is no longer functioning properly and the left hemisphere is compensating – it is kind of in overdrive. And so I realised that we are all doing something like this in the modern world. So that’s how I came to write The Master and His Emissary.

Richard: You explain in the book that it is not a question of the two hemispheres doing different things: every brain function – vision, speech, learning, etc. – involves both spheres, but they participate in different ways. So it is a matter not of ‘what’ they do, but of ‘how’ they do it – the approach they take.

Iain: Yes. Stated simply: for ordinary everyday survival, every living creature has to be able to pay attention to the world in two completely different ways at the same time. One is the kind of attention which is committed to a detail – a tiny object, a seed, a twig, something that is needed for food, for shelter, something that enables us to manipulate the environment in such a way as to survive better. But we can’t survive if that’s the only kind of attention we pay. We need at the same time to be paying a quite different kind of attention, which is open, uncommitted, sustained, broad in scope, vigilant.

And over the course of evolution, the first kind, the very narrow attention to a fragment or a detail very precisely targeted, has been taken over by the left hemisphere, and the right hemisphere has been left holding the baby of the whole of the rest of experiential reality. The drive for manipulation is expressed in the right hand, which the left hemisphere controls, and in language, which is a way in which we can manipulate what we are doing in the company of others, getting together in order to achieve a certain goal and so forth.

If you pay attention to the world in two different ways, since attention changes what we find, it follows that there are two experiential worlds available to us. We’re not aware of this because the two modes are fused at a level below consciousness. There is one world in which everything is isolated, fragmentary, static, known, familiar, inanimate, decontextualized, relatively abstract, general in nature and wholly explicit. And there is another world in which everything is interconnected, flowing and changing all the time, is never ultimately certain and always needs to be considered in context. The first way of seeing is like a map; the second is like the territory, which is an infinitely more complex, beautiful reality. The embodied right hemisphere sees the world as animated and perceives it as full of unique beings.

The neuroanatomist Jill Bolte Taylor with her brain sculptures. In 1996 she suffered a massive stroke which disabled her left hemisphere function, including language. Her book about her recovery process My Stroke of Insight (2008) and her TED talk [/] were both best-sellers. Image: from The Divided Brain [/], at 41:47 minutes

The Matter with Things

.

Richard: The Master and His Emissary came out in 2009 and was very successful, both commercially and intellectually, in that it has been one of the most widely-discussed books of the 21st century so far. It has taken you ten years to produce The Matter with Things, which clocks in at almost 1600 pages. It must have been a massive undertaking.

Iain: I actually had no intention of writing such a long book, but in the end that seems to be what was required of me. After The Master and His Emissary, I had a contract with Penguin Random House to do a more popular book. People had said to me that the thesis of this book is very interesting; there’s a lot of stuff in here that is great but it’s buried in a very long exposition, so maybe you should write a shorter one that would be more accessible? So I signed a contract with Penguin and started to write. But very soon I realised that it was a completely dotty thing to do with whatever time is left to me: to spend time expressing crudely, and without any of the nuances, things that I had already said at greater length and more subtlety – and to hope that this lesser version would become more popular than the original.

What I actually needed to do, I realised, was to unpack the philosophical implications of the fact that we interact with the world through a brain which is divided into two hemispheres that see things in completely different ways. How do we know which one to trust? I talked to my editor about this, and he said, ‘This sounds fascinating. Go ahead.’

Then I turned up with a manuscript which was three times the agreed length! It was supposed to be 200,000 words, and it was about 591,000 words after taking into account the bibliography. And my editor just sat on it for five months, without saying yes or no, or anything remotely like it. Eventually he came back to me and said, ‘Yes, we want to publish it. It’s great, it’s important,’ – it’s this and it’s that… ‘But it’s far too long. It needs to be half the length.’

I’d been prepared to make cuts, of course, but I was thinking of 10 to 15%, not 50. So I asked some of my colleagues and friends, who by that stage had read the manuscript: ‘You have to be brutally frank, because I can well believe that a shorter book is better. Would it be improved if it were half the length?’ And they unanimously said, ‘No, you’d lose far too much.’ So this presented me with a dilemma. I didn’t want to tout it to another university press because I thought they’d probably sit on it for another 15 months, and I was already talking about the content in public. I really wanted to engage in a conversation with people about it. So I decided to publish it myself. I’d never published so much as a pamphlet in my life before, but for some reason I thought that I could do it.

Then at the very last minute, Perspectiva offered to produce it. Perspectiva [/] is a sort of charity which is engaged in developing new perspectives and I sit on its board. But although the book came out with their name on it, effectively it’s self-published, and that is wonderful because I got to make all the important decisions about the typesetting and the binding and the paper and so on. The cover illustrations, for instance, are paintings by Ross Loveday that I have in my house here in Skye.

Philosophical Implications

.

Richard: Can you give us an idea of the main arguments you develop in the book? I know that is a difficult thing to ask given its length.

Iain: In Part One I address the question: if we get two different versions of the world offered to us by our brain, which one should we pay more attention to? I look at what I call the ‘portals to reality’ – the ways in which we can get some handle on the world. We do this primarily through attention and by perception; by the judgements we form on what we attend to and how we perceive it; how we understand it, using our emotional and social intelligence, and also our cognitive intelligence; and finally, how we exert a degree of creativity which enables us to enter into and see what it is we’re looking at.

And the conclusion I came to is that in every one of those cases, the right hemisphere is more reliable, more veridical, than the left. This is made very clear by the fact that all, or very nearly all, of the major delusional or hallucinatory disorders that neuro-psychiatrists encounter are far more common and far more severe after damage to the right hemisphere than after damage to the left. I drew upon an enormous amount of work in reaching this conclusion: firstly, my twenty years of clinical experience and research, then a further ten years of research whilst I was writing the book, as I gave up my clinical work to concentrate upon The Matter with Things.

Now, people might say, ‘Surely you have put your thumb in the scales. There must be something the left hemisphere is good at.’ And the answer is that there definitely is. It’s what I call apprehension rather than comprehension. In other words, getting a grasp, not in the sense of a mental grasp that allows you to understand, but literally getting hold of stuff and manipulating it. To put it in a rather crude soundbite: the goal of the left hemisphere is manipulation; the goal of the right hemisphere is comprehension and understanding.

So the left hemisphere is very much better at grasping and using tools, and at calculating, which is not the same as mathematics; the right hemisphere is much, much more gifted at mathematics, but the left hemisphere is better at simply carrying out procedures, therefore at doing calculations. It’s also better at everyday language. But the aspects of language that enable us to get beyond the everyday – those that take us to the realm of poetry or the realm of the spirit – are given by the right hemisphere, which, as I said before, understands all the things that need to remain implicit.

So having established that in the first part, in Part Two I ask: what are the routes we can take towards gaining some idea of what we can take to be reality? And whilst I very strongly defend science and reason as a means of doing this, I also show that they have limitations. There are limits to what we can ask of reason, and limits to what can be asked of science. I also consider intuition and imagination, which equally have their limits and can be routes to deception. But then, so can simply following reason in a blind way, or using science to try and explain things that it is not set up to explain because it starts from assumptions that rule out certain things.

And then in Part Three I try to show that these different pathways of knowledge are not in conflict with one another. In fact when followed properly, reason, science, intuition and imagination lead to positions that are complementary to one another. But usually this is because the important part of each of them – including science and reason – is offered to us by what the right hemisphere gives, not the left. So when we take all these together, that’s what we find in the world.

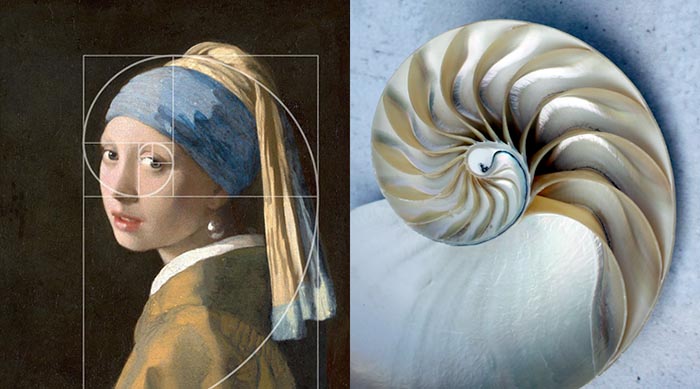

The ‘Golden Mean’ embodies universal values of beauty and harmony in both art and nature. Left: The Girl with the Pearl Earing by Johannes Vermeer (c 1665) showing how it is composed according the principle. Image: fstoppers.com. Right: The ‘chambers’ of a Nautilus shell, which increase in size with the golden ratio of 1.61. Image: Shuttlestock

Consciousness, Relationships and Values

.

Jane: The underlying argument of The Matter with Things is that the world is not in fact made out of ‘things’: that matter is not ontologically primary. What is primary is consciousness, and related realities such as relationships and values.

Iain: Yes, the title reflects my belief that we are obsessed with materiality in our society, and that a philosophy of reductionist materialism has taken over in science and even in many university philosophy departments. I see consciousness as something that we cannot derive from matter, if by matter we mean something that has nothing of consciousness in it. In fact, I think that consciousness is an ontological primitive, meaning that it is something that we can’t derive from anything else, and that matter is a phase of consciousness. I mean a phase in the sense that physical chemists use the word, not a temporal phase.

So, for example, water has three phases. In one, it’s transparent and liquid and flows over your hand. In another, it’s opaque, hard and very cold and can split your head open; it doesn’t move until given a push. And in yet another, it’s diffused in the atmosphere all around us; we can’t see it, but we couldn’t live without it. So which of these is water? Well, I’d say that they’re all really water, although we commonly think of it as being the liquid one.

So I think that consciousness has a phase in which it is matter, and rather by analogy with the water situation, we don’t have to say that one of them is primary. But if one did, I’d say that consciousness in its non-material form is primary, and the manifestation as matter is a sort of secondary element in the picture. And that’s the way most spiritual traditions have seen the situation.

Jane: Some spiritual traditions would see the matter phase as very much inferior – even something to be rejected or transcended – but that is not your point of view.

Iain: Not at all. I think matter has a very definite purpose, which is to provide endurance for a while; and resistance, as I believe that no creation happens without resistance – that nothing can come into being without resistance, and that indeed there is a coincidence of opposites. By this I mean that everything carries its opposite with it and that it can’t escape from this and shouldn’t try to, because it’s out of this conjunction of opposites that everything then arises. Permanence is always a matter of degree. Nothing is permanent, but matter gives things a little bit more permanence to things for a while, rather than just being in our thoughts.

Jane: Lots of people are arguing now for this primacy of consciousness, but you are unique I think in extending the idea of primacy to other non-material realities such as relationships. You argue throughout the book that relationships are prior to the things that are related.

Iain: Yes, and that is so paradoxical to the modern Western mind that a lot of people would say that can’t possibly be right. How can there be relationships until there are things to relate? But in fact there can be no things to relate until the relationships are there, because the relationships make the things what they are – rather in the way that consciousness precedes matter. I perhaps need to qualify that remark. I would not necessarily say that consciousness is prior to matter; it is better to think of the two as complementary aspects of a single phenomenon. So I could accept the argument that relationships and the things that are related come into being together.

However, for reasons that it would take me more time to go into than we perhaps now have, I think that relationship is, again, absolutely primal in the cosmos, and that whatever we mean by the creative divine force – however we may conceive of it – it is effectively relationship. This again, most spiritual traditions have put in their own way, such that God is love or whatever. Nowadays, even in physics, it is known that forces are primary, as it were, and that the things that we see and are able to measure are secondary to, and derive from, the relations of these forces.

The other thing you mentioned is values – and yes, I take the position that we can’t derive values from anything else either – that they are like consciousness in that they have to be ontological primitives. And I’m glad to say that there are atheistic philosophers of great distinction who hold this view as well, so in this case I don’t feel like I’m saying anything particularly unacceptable to your mainstream philosopher. Max Scheler [/] (1874–1928) also proposed that values are primary elements in existence. We don’t derive the colour blue or green from something else; we perceive blue and green. In German ‘perception’ is called Wahrnehmung – the ‘taking of truth’. Scheler coined a word Wertnehmung – the ‘taking of value’ – because he thought that things have intrinsic value that exists without us having to reason towards them or derive them from any other place.

Like him, I see value as absolutely essential to the business of being in the world. For me, the main ones are the classical virtues of goodness, beauty and truth – plus the sacred, which gets a whole chapter of its own at the very end of the book. It is the longest one in the entire work and was also the hardest to write.

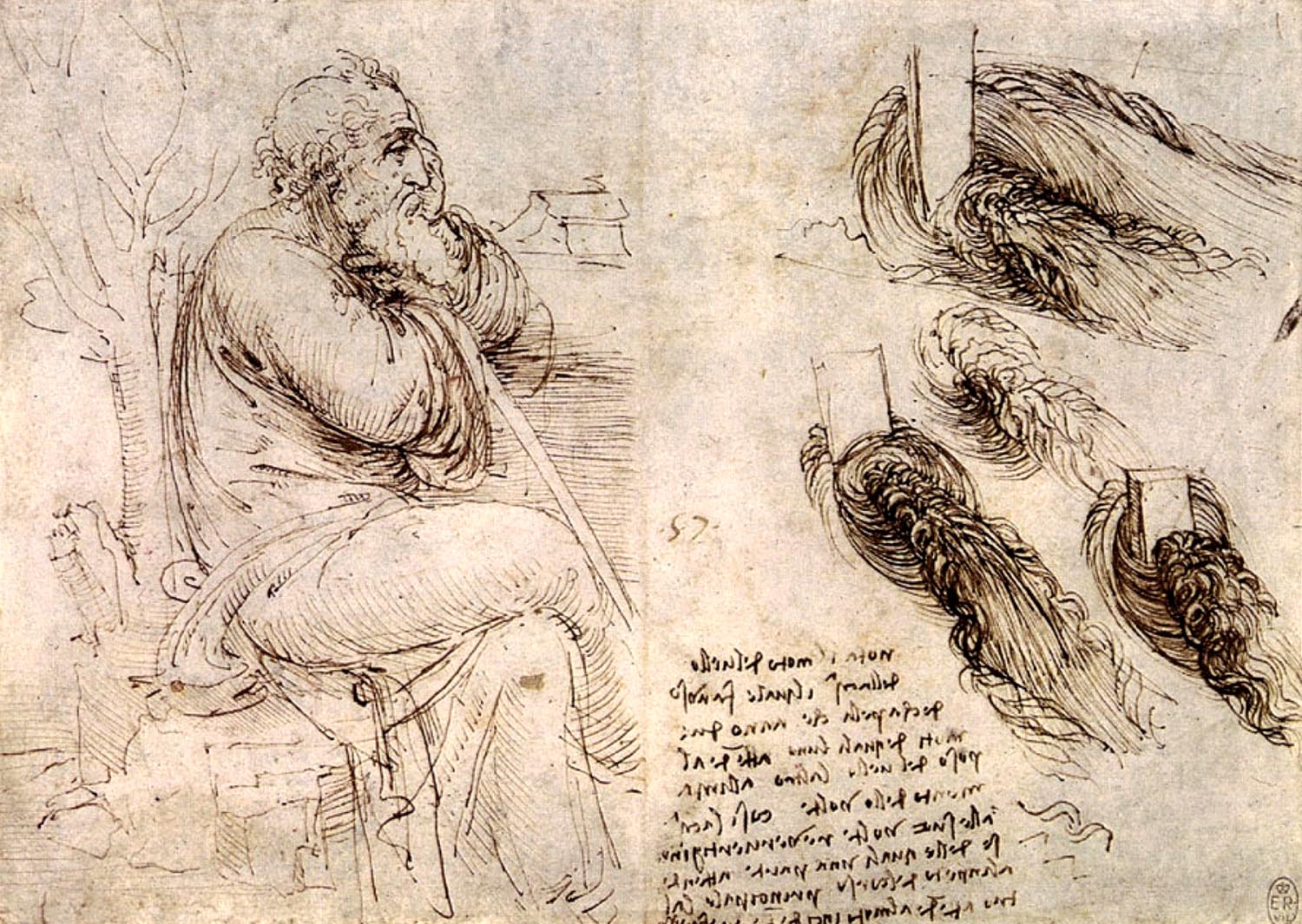

Seated Old Man and Studies and Notes on the Movement of Water by Leonardo da Vinci (c 1510). Leonard was fascinated all his life by the way that water flows and forms vortices, whirlpools and turbulence. Image: Royal Collection Trust, RL 12579, via Wikimedia Commons.

Move your computer mouse over the image in order to enlarge

The Problem of Time

.

Richard: I hope that we will get onto a more detailed discussion about this chapter later. But can we talk first about another radical idea in your work, which is your understanding of time. The conventional understanding is that time is fragmented. It’s made up of instants, and the instants make up longer periods, and so on. Whereas you are saying: no, it’s a flow, it’s a flux, it can’t be chopped up, it just moves along. Indeed nothing, absolutely nothing in existence is static. So you turn our ordinary understanding around, and say that what has to be explained is how things can appear to be at rest.

Iain: Yes, rest is a condition which they can only ever approximate, never experience absolutely.

Richard: So the implication of this is that once we understand or accept that time flows in this way, everything around us seems to be alive – or we can see it as alive – whereas in the more traditional view it becomes dead and inert. So by taking this point of view, we are in fact revitalising the world, reanimating it.

Iain: That’s right. But it is not that somehow motion brings life and the absence of it doesn’t, because obviously a machine can move. Rather, it is at the core of the right hemisphere’s take on the world that it is animate and changing. Therefore, by re-engaging this vision of things as interconnected and flowing, we are revitalising, rejuvenating, the right hemisphere’s mode of perception, which includes the view that what we are seeing is essentially alive.

Jane: This is another idea which has been expressed by the spiritual traditions through the ages.

Iain: Yes indeed; the notion that everything is changing, moving and flowing is something that ancient wisdom in Japan and China takes completely for granted. In Buddhism, also, it is a central tenet, and in the work of Heraclitus (c.500 BCE), who is my all-time favourite philosopher – a pre-Socratic. His most famous sayings are: ‘Everything flows’, and ‘You cannot step into the same river twice’.

It is also an idea that has been taken up by philosophers over history in different ways. Interestingly, you can find it in Enlightenment philosophers such as Diderot (1713–1784) and Leibnitz (1646–1716). I have been particularly interested in the work of Henri Bergson (1859–1941), a much neglected philosopher who’s been completely misunderstood. There’s a sort of circularity to the process where people misunderstand a philosopher, then don’t read them and therefore never understand their philosophy, and I think we’ve got into that cycle with Bergson. But actually, Bergson is very readable, and anybody who tackles him will find their eyes opened. Very little surprises me or astonishes me nowadays, and I’m not in the habit of marking books, but my copy of one of his books has markings in the margins throughout because he had so many insights that I had not come across before.

And one of these – perhaps the most important – is about the nature of time. He saw that time is a seamless flow in which whatever parts we detect are simply post factum divisions made by the analytic part of our mind, which we now know is the left hemisphere which has a representation of time in which it is cut up. But the actual process of time is constantly moving on and can’t be cut up. So he says, for example, that I can move my arm from point A to point B and retrospectively say there was a point C on this arc where my arm was. But in essence there was a seamless flow, so it wasn’t that my arm went from point A to point C, then C to B. No. There is no way you can get from points to a flow, any more than you can get from points to a line.

Extension is something fascinating in philosophy, and what Bergson calls ‘extension in time’ is more interesting than extension in space, although essentially it is just another example of it. You cannot make a line out of points, because a point by definition has no extension at all. So even if you put an infinite number of them together, you can never get a line. A line is something new. It has duration, and it’s that element of duration which is always changing and flowing. Bergson gives the example of a melody in a piece of music, and he likens this to the process of time passing.

All this has been especially important to me because of my study over the years, both at first hand and in the literature, of patients with schizophrenia. I must have seen thousands upon thousands of these patients and they are absolutely fascinating. The subject has been written about extensively, but mainly by French and German writers who are not translated into English. So I hope I have done a service in translating some passages from them in the book. The important thing for our conversation is that some of the very best of these writers – five or six of the greatest ones – propose that at the centre of schizophrenia is a problem with time – the misunderstanding of time.

Schizophrenic subjects often have a sense of time being composed of ‘now’ and ‘now’ and ‘now’; they may even describe it as a juddering film or a set of still photographs. And this lack of a sense of seamless flowing spills over into their actions; they often move in a jerky way and they sometimes literally can’t see how to get from sitting down to standing up, which is the next movement they have to make. This is one of the reasons I am so interested in time: it is so fundamental and misunderstanding it causes the world to fall apart.

Jane: So this reinforces that idea that the right hemisphere is not working well with schizophrenic patients.

Iain: Yes. And also goes back to Louis Sass, on the connection between modern life and schizophrenia – the idea that we’ve lost the sense of what our right hemisphere can tell us. This is not just about time, of course, but time is a very important central factor in the contemporary misunderstanding of the world.

Move your computer mouse over the image in order to enlarge

The Sacred

.

Richard: You’ve said the longest chapter in your book is on the sacred, which you see as the highest value. So we’d like to talk a little bit about your understanding of what you call ‘The All’ and what it means to you. At the end of the chapter, you say:

It is our duty […] to find out the core of wisdom in this ill-understood, though universal, insight [that there is a God], for that there is such an inestimably valuable core seems to me more credible than anything else I know. (The Matter with Things, p. 1333).

That’s quite a bold statement to read in a book these days, especially one addressed to scientists and philosophers.

Iain: Well, it is – especially as just before this, I say that despite my being resistant to, or even suspicious of, a great deal of ‘God talk’, I nonetheless think there is something being reached towards that is of inestimable value. In fact, in my experience, it is that, above all else, which is of inestimable value in life, and it comes through many other things, through other values such as beauty, goodness and truth.

It is a fundamental value but it is impossible to say what it is. So even before I started to write this chapter, I knew I wouldn’t succeed. I can’t define or describe what the sacred is; I can only say what it clearly isn’t, and dispel illusions. But that’s perhaps a worthwhile undertaking in itself – to clear a path so that people can get a glimpse or even a vision of what one is talking about. This is what is meant by the apophatic path in the spiritual traditions.

Richard: One thing that you say follows on from what we have already mentioned about relationships. You see relationships as centrally important, and the most important relationship of all has got to be with the All. You also say that the nature of relationships, unlike what perhaps Newton thought, is that they are always mutual. So if we have a relationship with God, then God has a relationship with us, and we have an effect on one another. In fact you seem to imply that we and God are co-creators of one another.

Iain: That is indeed my rather unusual claim. But it follows naturally from everything that I have argued for earlier in the book – that all experiences are an encounter between whatever it is in me and something other than me, and this is a necessarily reverberative or reciprocal event in which whatever it is is changed by my knowledge of it. It changes and the knowledge of it changes me in turn. Understanding encounters like this is not only a way of making sense of our experiences in life. Nowadays physics also tells us that the observer is changed by what is observed, and even more importantly and rather surprisingly perhaps, the observed is changed by the observer.

So it’s been argued by one of the most brilliant minds of the last hundred years – that of Alfred North Whitehead (1861–1947), who after all was a very rigorous philosopher, the co-author with Bertrand Russell of Principia Mathematica – that God and the cosmos bring one another into being. By ‘God’ is meant the divine source, however we might conceive of it. It’s had many names at different times throughout the world – li in China, in Sanskrit rta, allah in Islam; it was the logos in the old Greek world before it became simplified to the idea of either a word or reason. And so whatever this thing is, it is somehow creating an ‘other’ and moulding and shaping that other; but that other also, to some extent, moulds and shapes what is coming into being. The consequence of this is that we have a moral obligation to attend to the world in a way that will allow us to see what is potential in it of beauty and value, and to help actualise it.

Richard: So you have come up with what you call ‘McGilchrist’s wager’. You take the famous wager expressed by Pascal and add a third option.

Iain. Yes. So just to outline very briefly Pascal’s Wager: Pascal (1623–1662), of course, was both a brilliant mathematician – one of the greatest that ever lived – but also a very spiritual man. He proposed that either there is a God or there isn’t. If there is a God, then it’s extremely important that we get to know that God; but if there isn’t a God, it won’t have done us any harm to attempt to get to know this idea we have of a God.

But that has never seemed to be entirely satisfactory for a number of reasons, one of them being that it seems rather self-regarding – a way of saving our skin. Also, can we really decide whether we believe in God or we don’t? I now think we can, but as a younger person I didn’t think so. I now realise that in a very Pascal-like manner, you can learn to understand something by adopting an attitude, a disposition of your life towards it as if it were true, and thus find out whether it is true or not. So that is one way of getting around that problem.

As for ‘McGilchrist’s wager’ – well, it’s like Pascal’s in the first two points but it adds a third: that it’s not necessarily the case that God either is or isn’t. Whatever this God is, He/She/It is constantly becoming. God is not so much a being as a becoming, although strictly speaking, I accept that it is possible to be a being within the concept of becoming, for God at any rate. But the point that I’m getting at is that we have an influence on how and in what way this divine-whatever-it-is manifests itself and actualises itself. We’re not just these terribly insignificant creatures that some scientists would have us believe – so what does it matter what we do or what we say? We have an important role to play.

Richard: You talk about the need to rediscover the All, which also means discovering the concept of wholeness and health.

Iain: Absolutely. In my concept of the All, I’m very influenced by the philosopher Schelling (1775–1854), who is another neglected thinker these days. He wrote amazingly even as a young man about the importance of flow, of resistance, of producing something out of flow; he talks about the coming into being of eddies and so on in the flow of the water – but I won’t go off down that track at the moment. For Schelling, our relationship with the All is the one thing that matters at the end of the day. And the purpose of all our other knowing and experience is to be able to understand this and not forget our crucial relationship with the All.

I discovered in a much more hard-nosed way from scientific research that there are three particularly important relationships that seem to govern our happiness and sense of fulfilment as human beings, in terms of our physical, moral and spiritual health. And these are, firstly, our relationships with one another; secondly, our relationship with the natural world; and thirdly, our relationship with the divine or the spiritual, whatever one wishes to call it.

Getting these relationships right can have very, very profound effects. So spending time in nature, or belonging to a well-knit community that lives together and shares beliefs, shares trust, shares rituals and so forth; or just generally having a spiritual relationship to the world (whether you belong to a group of such people or not). These things have significant effects on our mental well-being: on resilience, on happiness, on levels of anxiety, on being able to cope with misfortune, on moral qualities. They even have an effect on simple physical health: in fact, they are as important as things like stopping smoking, losing weight or going to the gym three or four times a week.

These effects are incontrovertible, based on a colossal amount of data now, and I go into it in some detail in Chapter 28 of The Matter with Things. It was all complete news to me. I’d written a bit about the value of belonging to a society before, at the end of The Master and His Emissary, where, amongst other things, I describe a community in the east of America called Roseto, which was effectively a transplanted community from Italy, in which people kept their normal ways of being in and out of one another’s houses, eating together, sharing their pleasures together, worshipping together and so on. A study found that despite the fact that this community had less than optimal habits in terms of drinking, weight, smoking and other things, it had lower levels of mortality, even cardiovascular mortality. And during the last ten years, we’ve also come to know a great deal more about the effects of spending time in nature. But what was a real eye-opener for me, and which I came upon most recently, is the extensive literature on the physical and mental health aspects of having a spiritual dimension to one’s life.

Creative Restriction: Consciousness and the Brain

.

Richard: Going back to the question of consciousness, you explore three possible relationships between consciousness and the brain. One is that consciousness arises from the complexity of the neurological processes in the brain, which is the view of most scientists who are wedded to materialism. Or it could be that consciousness is primary and universal, and the brain acts as a transmitter for it, like a sort of radio receiver. Or – and this is the view you favour – it’s a matter of the brain granting permission, meaning that it grants entry to some thoughts but not others. But this begs the question of the origin of those thoughts.

Iain: Well, as I have already said, I believe consciousness is a fundamental quality of the cosmos. So consciousness exists and permeates everything.

Richard: So this would be what we call the divine – the divine nature of consciousness.

Iain: Yes, this is what is referred to as the divine or the sacred, the origin, the fons et origo of everything – the creative force.

As for the function of the brain: it is a familiar idea that a visitor from outer space could not tell by looking at a television-set whether it was generating the programme or receiving it. It’s equally difficult just looking at the brain to know whether it’s generating what we’re experiencing or whether that comes from somewhere else. If you believe that consciousness is primary, then clearly you take the latter view. My particular interest is in the idea of permission rather than transmission. Pure transmission would mean, presumably, that we’d all be transmitting the same programme. Whereas what permission does is something very creative. Here I come back to something I mentioned before: the creative value of resistance. A very nice image for this is William James’s remark that his speech is caused by the air coming from his lungs out of his mouth, but if it weren’t for the intervening obstruction caused by the larynx, he wouldn’t have a voice. And I think that’s a lovely idea because it shows that, so often, less is more – that it is by restriction that we cause something new to come into being.

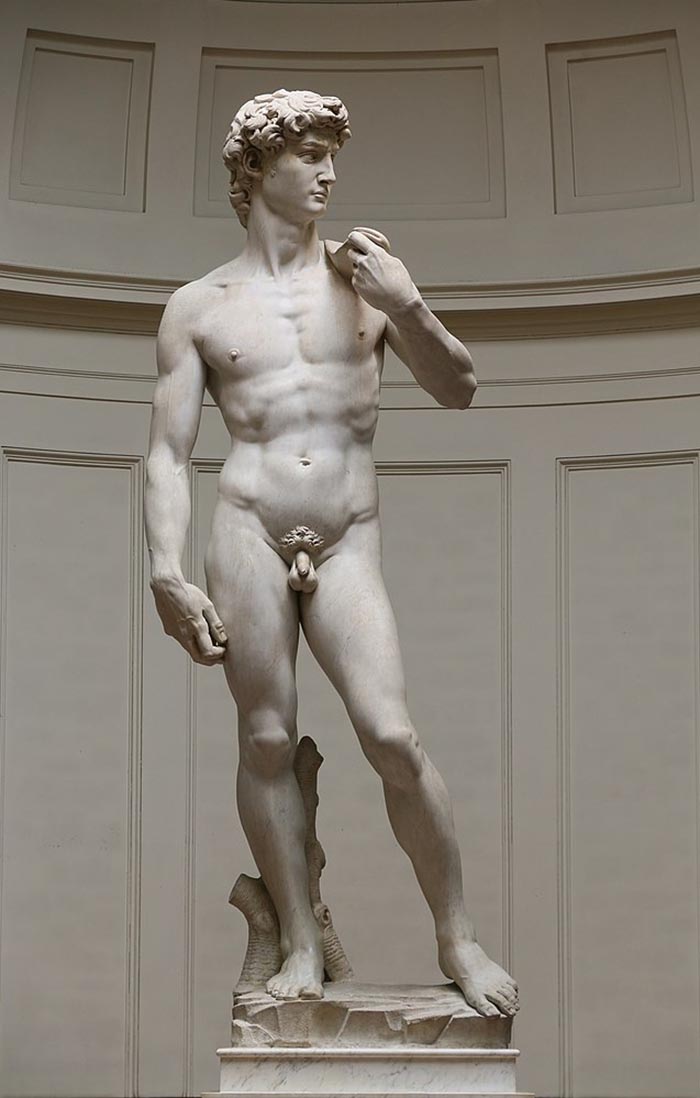

This is a point that I look at from many different aspects in the last third of the book. Another example is drawn from sculpture. Think of Michelangelo’s David. Here we are not looking at something that was put together; we’re looking at something that was discovered by throwing away stone. That’s what Michelangelo did: he discarded stone and there was the David. He didn’t do a hand and put it on an arm, and then put that on a torso, and so on.

Jane: So by ‘permission’, you mean that the brain is like a receiver that filters or selects what it allows through?

Iain: That is a way of putting it. Or is it the sculpture? There are different analogies one can make. What I’m saying is that the brain is the means whereby global consciousness becomes the individual consciousness that I experience, and that it does this as much by obscuring or hiding things as by making them happen. So the brain shapes consciousness in just the way that the larynx shapes the wind, the breath, the air, so that it becomes a voice.

And so for a while, some part of consciousness seems to be corralled, if you like, inside my being. From inside that being, it can maybe look as if that is all the consciousness that is there. But actually it’s continuous with every other consciousness. An image I sometimes use to express this is to imagine an enormous cell the size of the universe that has many, many outpouchings in the way that cells do. If you were inside one of those outpouchings, something like pseudopodia, everywhere you looked, you would see a membrane that enclosed you, and you wouldn’t see the rest. But if you looked at the little part, perhaps only 2% of what surrounds you, at the base, you’d see that in fact it is entirely continuous with the cytoplasm of the whole cell. So an individual consciousness is never entirely separate from the whole consciousness, even though for a while it’s corralled into something individual.

This is another example of resistance or restriction causing something unique to happen. I believe this process is profoundly the purpose of the cosmos – to produce forever more individuated beings out of the whole that is One. And to do this without in any way threatening or impinging on the integrity of the whole. In fact, quite the opposite: the unfolding into individuation fulfils and makes more the whole. You might think of a tightly furled bud unfolding and unfolding and unfolding, and at every unfolding, more and more of the flower comes into being. It is this expansion that I believe is the drive of the cosmos; it is always towards individuation, but without this having, as I say, any negative impact on the sense of there being an All.

Here we find a correlation not only with the ancient Buddhist idea that there is the One and the many things, and that they are different manifestations of one another. But there’s also Heraclitus, who says that it is wise, listening not to me, but to the logos – that is, to the grounding spirit, whatever it is which is divine – to see that the One is all things. Because of the way the Greek language works, you can see this as meaning either that the One is all things or all things are One.

Jane: This is such beautiful vision because it indicates that for each individual – what you call each individuation – is not really lacking anything in respect to the All; rather it is a particular manifestation of it. And I love the sculpture idea because it brings in the idea of beauty – that what is discovered as this creative restriction takes place is beautiful.

Iain: Yes. Beauty – the realisation of beauty and the realisation of ever greater complexity – is one of the drives that we can easily see in the universe. So I see part of our role here as trying to respond as fully as we can, while we’re given life, to these values. Because we don’t invent them; we discover them.

Future Work

.

Jane: So just to finish: now that you’ve done this book, what do you see ahead of you? I know that you are very busy discussing the ideas in The Matter of Things in various forums and seminars. But are you planning any further writing?

Iain: Absolutely not. I mean, I may write the odd article, but I have no desire to write at all. In fact, I feel quite allergic to writing. What people don’t understand is that I suffer terribly through writing: all my life I’ve hated doing it, although I like the state of having written. People tell me that it does not look as if I find it hard when they read me, but that is because I take terrific pains over everything I write. So, no; I want to smell the roses and spend more time with children and grandchildren. There are a couple of things that I’d like to write about if I have enough time left, one of which is a short book about the paintings of psychotic subjects, which I think would be both beautiful and fascinating for people who don’t know the field.

The philosophy that I’ve written about in this book is really the outcome of a life’s quest that started as soon as I could start thinking about these things at all. I’ve always believed, since I was a teenager, that the world is not inert – that we are not just passive photographic plates that register impressions of light, or a recorder that records sounds. It is rather a matter of an encounter – a meeting – in which we go to meet the world and the world comes to meet us in its own terms. What we find there is dependent on the attention we pay to it. So I’ve always thought that what surrounds us is something that is living and has a depth that we can only begin to fathom. I’ve also always thought the whole is more than the sum of the parts and so on.

But now I have said what I have said, which is why I found the wonderful words of Angelus Silesius (1624–1677) so delicious when I came across them just as I was approaching the end of the book.

Friend, this surely is enough. And should you want to read more,

Then go and become yourself the words, and yourself the Being

(The Matter with Things, p. 1333)

Richard: Thank you so much for talking to us and giving us an insight into the fascinating work you have been doing. There is much, more that we could ask, but you have given us more than enough food for thought.

There are numerous videos and podcasts available of Iain talking about his ideas: see for example ‘The Divided Brain‘ on Vimeo and ‘The Divided Self and the Sense of the Sacred’ on YouTube. He also has his own site Channel McGilchrist [/].

Image Sources (click to close)

Banner: Iain near his home on the island of Skye, Scotland. Image: from the video Making Sense, 1.27

Inset: Portrait of Iain McGilchrist. Photograph courtesy Iain McGilchrist.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] IAIN McGILCHRIST, The Matter with Things (Perspectiva Press, 2021).

[2] IAIN McGILCHRIST, Against Criticism (Faber, 1982).

[3] OLIVER SACKS, Awakenings (Duckworth & Co, 1973).

[4] IAIN McGILCHRIST, The Master and His Emissary (Yale University Press, 2009).

[5] JOHN CUTTING, The Right Cerebral Hemisphere and Psychiatric Disorders (Oxford University Press, 1990).

[6] LOUIS SASS, Madness and Modernism: Insanity in the Light of Modern Art, Literature and Thought (Harvard University Press, 1992).

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Panpsychism and the Problem of Consciousness

Richard Gault explores a revolution in scientific and philosophical thought which posits consciousness, not matter, as the fundamental principle

Memory, Habits and Wholeness

Biologist Rupert Sheldrake challenges the dogmas of conventional science, and explains how recent research supports his alternative theory of morphic resonance

Mind over Matter

Scientist and philosopher Bernardo Kastrup discusses his critique of the materialist paradigm and argues for reality is essentially mental

A Biology of Wonder

An interview with scientist Andreas Weber, whose radical ideas are transforming our understanding of nature

READERS’ COMMENTS

What a wonderful dialogue with Iain. Thank you so much Richard and Jane for responding to the creative forces in you that sculpted this! I could relate a lot of what he said to the Arabi’s cosmology and it was so good to here these same ideas expressed in contemporary language.

With much gratitude

Thank you. Much wisdom with Iain.

The last time I felt this way about a review was one about “The Dawn of Everything,” and that book changed my life. I have bought “The Matter with Things,” and I expect a similar outcome.

This is a fantastic interview with intriguing ideas. It is too bad that Iain doesn’t want to write more, because I believe that AI and LLMs are another domain of exploration of this idea that will yield fruit. Perhaps the underlying math of LLMs isn’t so much a model of neurology as another interface with universal consciousness?