metaphysics & spirituality _|_ Issue 27, 2024

The Philosophy of Prayer

Distinguished theologian George Pattison talks about the meaning of prayer in the modern world and how it brings us to awareness of our essential nothingness

The Philosophy of Prayer

Distinguished Anglican theologian George Pattison talks about the meaning and practice of prayer in the modern world

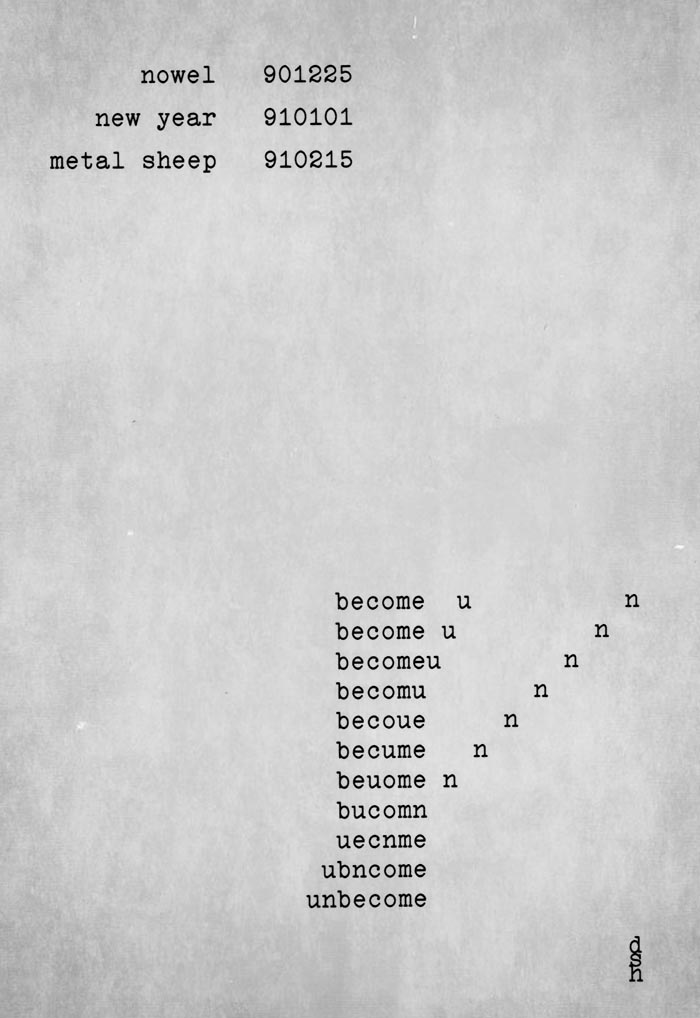

George Pattison is a theologian and retired Anglican priest who, during a distinguished career, has been Professor of Divinity at the University of Glasgow and the Lady Margaret Professor of Divinity at the University of Oxford, as well as holding posts in Germany and Denmark. His range of interest has extended from existential philosophy as it has been expressed by writers such as Kant, Kierkegaard and Dostoevsky to Eastern philosophies and the aesthetics of film and the visual arts. He has published over 20 books, the latest of which, The Philosophy of Prayer, subtitled Nothingness, Language and Hope,[1] explores the way in which the practice of prayer leads us to silence, essential contemplation and a deep understanding of our existential nothingness. He talked to Jane Clark and Peter Huitson from his home in Scotland. The piece is illustrated with renderings of nothingness/realisation by modern artists.

Jane: Your book is published as part of a series called ‘Perspectives in Continental Philosophy’, and although you also talk about some traditional texts such as The Cloud of Unknowing, it very much focuses upon thinkers such as Kant, Heidegger, Kierkegaard and Dostoevsky. Is this because you think that these people have something especially valuable to say about prayer that we don’t find in, say, American or British philosophy?

Jane: Your book is published as part of a series called ‘Perspectives in Continental Philosophy’, and although you also talk about some traditional texts such as The Cloud of Unknowing, it very much focuses upon thinkers such as Kant, Heidegger, Kierkegaard and Dostoevsky. Is this because you think that these people have something especially valuable to say about prayer that we don’t find in, say, American or British philosophy?

George: Continental philosophy – sometimes also called Post-Kantian philosophy – has been the focus of most of my academic work in the last 20 years. One of the reasons I’m particularly attracted to it is that I think it expresses the general frame of mind of people in the modern world. In particular, it articulates what one might call ‘subjectivity’, and the role of subjectivity, not just in religious life but in human life as a whole.

Jane: Can you say more about what this implies?

George: Well, Kant shows that our knowledge of the world is totally tied up with how we look at it. It’s not just the facts that are out there that matter, whether they’re metaphysical or empirical facts, but our minds themselves contribute to – and help shape – what we perceive in the world. In the next generation after Kant, this subjectivity is variously glossed in terms of imagination or feeling or will. And it can be either individual, as in the case of Kierkegaard, who says that subjectivity is truth, or it can be collective, as in the thought of Marx and Hegel. Once we have the Marxian category of class consciousness determining over how we see the world, human history also enters the picture. This means that how we experience the world becomes dependent on where we are in history, what we’ve inherited from the past, and what we think about where we’re going in relation to the future.

In other words, in this philosophy, the world has been radically humanised. It is what we see it as, or what we want it to be. Human beings no longer feel constrained by an impermeable external reality, but can make their own.

It is not just philosophers who think like this now, but most ordinary people also largely think in these categories. So we hear innumerable interviews on radio and television with, for example, athletes who say: my story shows that anyone can be whatever they want to be. This is the great modern principle of autonomy – that the meaning of our lives is what we put into it. One hears Sartre’s saying ‘I am the sum of my actions’, echoed all the time in interviews and in literature. It pervades our modern consciousness. The continental tradition engages with this. Many thinkers in that tradition want to support this principle; some thinkers are more critical, but still they take that agenda very seriously.

Jane: When it comes to prayer though, you begin your book with a critique of Kant. In particular, of his idea is that we are in charge of our own destiny – that as moral beings, we’re completely responsible for our actions and capable of manifesting whatever elements of good are within us without recourse to any outside force. For this reason, Kant was not keen on prayer because it puts us in a position of passivity and implies weakness. You are obviously refuting that and asserting that there is a place for prayer within Post-Kantian philosophy.

George: That’s right. I think to be fair to Kant, he is obviously a sophisticated and thoughtful philosopher, and he acknowledged that, in all sorts of ways, we don’t create and invent ourselves. He recognised that we have bodies, we have feelings and we live in society; we don’t just invent ourselves out of nothing. But, nevertheless, he thought that the best way for us to be is entirely active – a bit like the medieval idea of actus purus, pure act. He believed that we should be a pure enactment of the moral will, and aim at maximising our rational activity.

However, I’m more influenced by Kierkegaard and others who would say: that’s all very well and good but the fact is that we didn’t invent ourselves. To use a phrase by the Protestant theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher [/], we are absolutely dependent on God, and our lives come to us as a gift – as something we receive. This has massive implications that the tradition of radical autonomy doesn’t recognise.

Schleiermacher acknowledged that we are active in all sorts of ways – he himself was a massively active person who translated the whole of Plato, was very involved in the politics of German nationalism and Jewish emancipation and many, many other areas of life. But he also maintained that our starting point always has to be that we are not makers of our own being, but we are before we start doing anything for ourselves.

This at one level seems to me to be a very common sense position. As we all know, we didn’t have a conversation with our parents along the lines of: ‘I’d like to exist; do something about it’. We wake into full consciousness at about five years old and realise that we’ve come from somewhere we don’t have any knowledge of. Heidegger’s expression is ‘thrownness’. We experience ourselves as ‘thrown’ into the world. And here we are. Gosh!

Jane: We don’t choose our characteristics either. We might want to be an athlete or a musician or whatever, but we don’t necessarily have the ability. We are as we are.

George: That’s right. I think that no amount of training would ever have got me to run 100m in less than 10 seconds. You’ve got to do the training as well, of course, but if you don’t have that original endowment, it’s not going to happen.

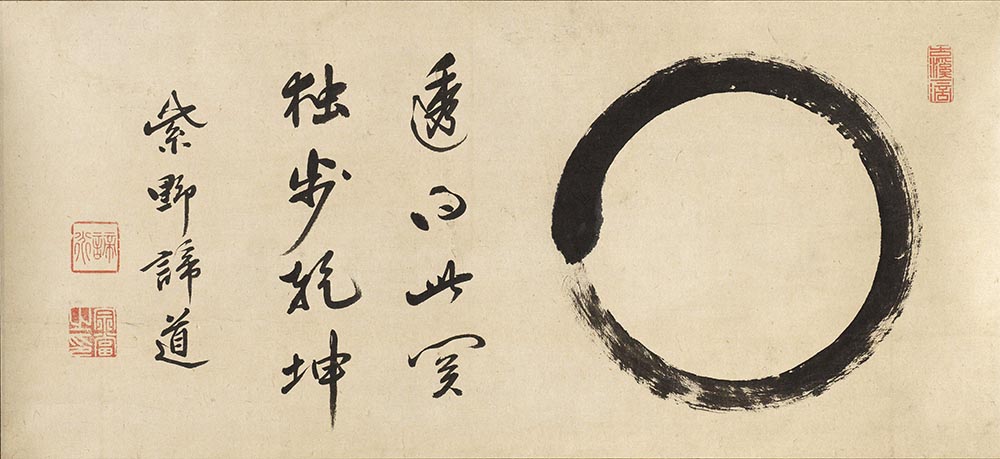

Skyspace by the American artist James Turrell, an installation at the Tremenheere Sculpture Park in Cornwall, UK. Photograph: Karl Davies

Prayer as Process

.

Peter: So how does the matter of prayer relate to this?

George: The Heideggerian notion of ‘thrownness’ is, very crudely, that we just wake up one day, and here we are. Then we’ve got to get on with life as best we can, recognising the reality of our situation. I think prayer is premised on seeing this ‘thrownness’ as a gift – something that elicits gratitude, wonder, love and praise. It is something to be infinitely valued and treasured. And I think that all of the vocabulary of prayer, in a sense, flows from that – the silence of prayer as we stop, as we make ourselves open to the grandeur and the sublimity of what’s given to us before any conceptualisation, before any words on our part.

Jane: The central premise that you develop in the book is that however we may start praying, it eventually leads us to a point of understanding this dependence upon God – in fact, to our existential nothingness. But we don’t necessarily begin by asking for emptiness; we might begin by asking for things. So you’re not talking about the sort of prayer that we do only at a point of crisis: when we are falling down a hole or something, and cry out: help, rescue me. It’s something that we engage with over and over again.

George: Christian writing about prayer has often made a basic distinction between petition on the one hand and contemplation on the other. A lot of the classical texts would say that petition is the lowest form of prayer, and then you go up the ladder until you get to direct contemplation of God.

I wouldn’t make the distinction that sharply because in order to be able to ask for anything, we already have to have a certain understanding of God, or of the one whom we ask, as basically having goodwill towards us. I mean, if we really haven’t a clue and we just go on and on asking for things, then that’s kind of meaningless. But when there is genuine intercessory prayer, it’s because we believe that the one who gives us being is full of goodwill and blessing towards us.

These things are often talked about in terms of relationships with parents and children. This can be misleading, but it is also true that when children in a happy household ask their parents for things, there’s an underlying sense that their parents will give them what’s best for them. Kierkegaard for one is very clear that this doesn’t mean that you always get what you ask for, because that may not be what’s best for you.

Jane: When you say that someone might not have a clue what they are doing and continue to ask for things, you seem to imply that prayer needs to happen within a metaphysical or theological framework. That that is a necessity for the process to take us from petition to realisation of our essential reality.

George: I think it’s important to say, first, that clearly a lot of people pray without any philosophising or any reflection on metaphysics. Rather, they pray with a kind of spontaneous trust, spontaneous confidence, spontaneous hope. And I think that for them, and for all who pray, the prayer itself enhances that confidence and trust and hope. So one doesn’t have to philosophise about it at all.

But I also think when one does start to philosophise, one can then see that the process involves certain assumptions about the kinds of beings that we are – our existential nothingness as we have just mentioned. This is not a new knowledge. It’s there in the 100th Psalm. ‘It’s He that has made us and not we ourselves’. We didn’t invent ourselves into being.

Jane: Something that has very much interested me is the phenomenon of secular prayer, which is remarkably common. To give an example: while I was preparing for this interview, I came across a book of poetry by Michel Faber in which the first poem is a prayer for a death without suffering entitled ‘Of Old Age, In Our Sleep’. It begins:

Although there is no God, let us not leave off praying

for words in solemn order may yet prove to be a charm.[2]

He reiterates later in the poem that he has no belief in God or any transcendent presence. And yet he prays.

George: I think I’d put that the other way round and say that to pray is to believe in God. Or to put it another way, what we believe in is revealed in how we pray. When people set out to pray, whether it’s in a church environment or as private individuals, there are all sorts of ideas about God in play, often drawing upon the conventional teachings of the church: God as father, God as king, all these kinds of images that shape the words we use and what we ask for. But an important part of the process of prayer is shedding all of these presuppositions and just letting the praying itself do the work. Allowing the process itself to guide the theologising and the philosophising.

There’s a very old Catholic saying: Lex orandi lex credendi, meaning: the law of praying is the law of believing. So if you want to know what someone believes, don’t just ask them what they believe because they might give you a very intellectualised answer, one that perhaps they think will fit within your cultural expectations, or defy them. But if you’re able to listen in to how they pray, then that will tell you far more.

Love and Contemplation

.

Peter: You talk about having to shed presuppositions about the nature of the one we pray to. Do you think this also includes dropping expectations – praying because we expect to receive what we request?

George: Yes. Very much. There’s an idea developed by Francis de Sales [/], an early 17th century French Bishop (later made a saint), of ‘the impossible possibility’, which was then taken up in the next generation by Archbishop Fénelon [/]. And it goes something like this: if you imagine that in the very next second you’re going to die and you know for certain that you will then either just go into oblivion – total annihilation – or even worse, that you’re going to go to hell and burn forever in hellfire: would you still love God? Would you still believe in that moment that God was good and gracious, and the giver of every good and every perfect gift?

It’s an ‘impossible possibility’ because even in that moment, none of us would really know what was going to happen next. And, for de Sales and Fénelon, this is not something that a God of love would ever do. So it’s a kind of extreme test regarding our motivation in prayer. Do we pray merely out of self-interest or out of a pure love of God? This idea goes back to the legend of the Islamic woman mystic Rabia [/], that was brought back to the West by the Crusaders. She was depicted as a kind of crazy woman who went around in the port of Basra with the fiery brand in one hand and a bucket of water in the other, to obscure the view of heaven and to put out the fires of hell.

Jane: There is a poem which is a kind of prayer in itself attributed to her, which translates like this:

O God!

If I adore You out of fear of hell, burn me in Hell!

If I adore You out of desire for Paradise,

Lock me out of Paradise.

But if I adore You for Yourself alone,

Do not deny me Your eternal beauty.[3]

George: Yes. We don’t love God because we’re going to get punished, or because we expect rewards, but simply because God elicits our love. Ultimately that’s the only reason for it.

Peter: You mention love, and that contemplation is about love. In the book you quote The Cloud of Unknowing: ‘The soul, when it is restored by grace, is made wholly sufficient to comprehend God fully by love’. This is assuming a view of God as love – of God turning us into love, turning us into His own nature. We are made in the image of God and somehow we turn more into His likeness through the act of prayer.

George: Yes, that’s right. Kierkegaard employs an image which he didn’t invent himself but which is found several times in the Christian tradition. Archbishop Fénelon, whom I’ve already mentioned, used it, as did Meister Eckhart and I think it’s quite likely that there were much earlier sources. This is the image of the sea. Kierkegaard points out that when the sea is turbulent and stormy, it doesn’t reflect anything. But when it is very still and calm, then it gives a perfect reflection of the sun. And the sun sinks down into the sea, and the sea both reflects and is transparent to it.

The sun here is a metaphor for the divine light, and the meaning is that at either the apex or the very depth of prayer – however you want to see it – the soul becomes still and calm and is able to receive again everything that God is giving it. Instead of trying to create itself, instead of trying to invent its own agenda, it has become entirely open to what’s being given to it. It is receiving it, accepting it with total acceptance, and in that sense is being re-created.

Peter: Yes, I think that’s exactly it. And that fits so well into the whole Christian tradition and the idea of resurrection.

George: And of course, there’s the opposite phenomenon, which is known to all satirists – of the person who tries to build themselves up, to impose their personality on all around them. And the more they do it, the more they show how empty and superficial they are.

‘Unknowing

.

Jane: In the book, there is a chapter entitled ‘Unknowing’ and another called ‘Mystery’. In these, you imply that prayer leads us to a point where we can embrace not knowing about things or perhaps better to say, we can embrace the unknowableness of the divine. Can you say something about that?

George: I’ve been a professional clergyman since I was 27. And there is, or has been, an assumption in our culture that professional clergymen have the answers to religious questions. So people think – and perhaps they have been told by the church – that there’s a kind of professional expertise in these matters, and if someone comes and asks questions about prayer, about themselves, about God, then clergy feel that they ought to have the answers. But actually, they don’t.

If there are answers – and I’m not sure that question and answer is actually the best analogy – then they’re God’s answers. You have to ask God, not the clergy or any other person. So I think clergy in particular need to do an awful lot of letting go. And not just the clergy. This is true of all of us. We have to find each other in this space of not knowing, this place of vulnerability and dependence.

At one point in the book, I talk about solidarity, and that is also absolutely basic – that as human beings in our God relationship, we are, to use a hackneyed phrase, all in it together and in a very radical way. At one point in my life I was quite keen on yogic philosophy, but one of the things that always made me slightly uncomfortable was the idea that you get in at least some introductions to yoga that people come into life at different stages of development. There are some people who are fated by their karma to remain at a pretty low level, while others are sort of halfway up and others are part of a kind of spiritual elite ready to go the whole way into enlightenment. I don’t accept that, because I think with regard to God, with regard to the basic reality and truth of our existence, we are all pretty much in the same place. To use the old Scottish expression, we’re all ‘Jock Tamson’s bairns’. We suffer together and we pray together and we look for a better world together. We do this as individuals, but we’re doing it together as well.

Jane: We find the same idea in the Islamic mystical tradition that Peter and I are familiar with. Ibn ʿArabi for instance talks about this knowledge of our complete dependence as a kind of bottom line. He acknowledges that there are distinctions between people, or between saints; they have different degrees of knowledge or insight. But for him the most essential characteristic of a saint is the realisation of their dependence upon the Real.

George: Yes – and it’s interesting to me that there have been a few articles over the years comparing Kierkegaard and Ibn ʿArabi or Kierkegaard and Sufism more generally. They share the idea that servanthood and worship are somehow hardwired into being human, and therefore if we think that the name of the game is maximising our autonomy, our mastery, our achievement, then we’re heading off down a totally wrong path. That will always end badly unless we rediscover that that’s not what we’re here for and take ourselves back to this place of servanthood and worship.

Peter: Is that what you mean by humility, which is where you get to in the final chapter of the book? You say that it has become ‘downgraded’ in the modern world and that we need to retrieve it and understand it in an essential way, as to do with acknowledging our nothingness.

George: Yes. That’s right. Humility is a basic comportment towards life, towards other human beings, towards God. Alongside this is the idea of reverence. Albert Schweitzer developed an ethical stance of what he called ‘reverence for life’, which I think is a wonderful expression. It implies a readiness to bow down before the wonder of the reality around us. This is beautifully expressed, I think, in, Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov by the elder Zosima, who is the epitome of everything that’s best in Eastern Orthodox spirituality (although I know that some think he’s a little bit unorthodox—albeit in an Orthodox way).

Zosima tells the story of his teenage brother, Markel, who is, in the way of 19th century novels, dying of consumption. Markel has been an atheist. He’s turned his back on religion, but in his last few days he starts to rediscover it, but in a very different way than the religion he was brought up in. He starts speaking with the birds and the flowers outside, asking the creatures of the world to forgive him. His mother says: you’re crazy, you haven’t done any wrong to them. Why are you doing that? But for him, this is a wonderful expression of reverence for life and his participation in the totality of life. He must ask forgiveness, though, because until these last days of his life he’s never really appreciated this. This passage points to the things that make our life worth living. Imagine if there wasn’t any birdsong. It’s a hugely important part of what we experience of the world.

Peter: You also mention in the book the joy of life, as was put forward by the French Emmanuel Levinas [/].

George: Levinas very much understood himself as a Jewish philosopher and affirms what has often been regarded (both positively and negatively) as the ‘materialistic’ character of Jewish thought. He believed that religious life begins with human life and that human life is full of natural pleasures that should be enjoyed. His philosophy is profoundly anti-ascetic. It’s not about trying to detach the spirit from the body, but rather of giving thanks for and using beneficially everything that comes with living in the body. This goes back to the biblical ideal of every man under his vine and fig tree – that these things are there for enjoyment and for the enhancement of human life. There’s a rabbinical saying I read many years ago in one of Victor Gollancz’s [/] anthologies, which was along the lines that we must answer on the Day of Judgement for every lawful pleasure we have not enjoyed.

Of course, there is danger here that we get into massive ethical and political arguments about what are the lawful pleasures and what are not. Those are all legitimate, but in those discussions, it’s so important that we don’t lose sight of the basic primal truths about who we are.

Calling God by Name

.

Jane: You talk about the act of prayer as not being about the accumulation of merit or knowledge or whatever, but as a gradual shedding, a giving up, of our preconceptions, our desires and all the images and ideas that we have about the divine.

George: Yes, I feel that the process of prayer – when it is not just a one-off thing or something you do for five minutes in church but a process that goes on over time, perhaps for years – involves learning what it is we really want to pray for or need to pray for. And for me, this means narrowing things down until the focus is increasingly on the one thing needful. I think that there may well be different spiritual types in this matter and that there are other people for whom it’s a more expansive process, always spreading out. But that’s not my way.

Jane: In the chapter on ‘Words’ you discuss this even in terms of the language that we use – that that can become more simple and essential to the extent that prayer can consist of a single word that is continuously repeated.

George: I actually take this from the medieval English treatise The Cloud of Unknowing, which is very clear on this point. It is a very practical book written by an anonymous author who I think was addressing people who were saying: well, all this theology and metaphysics sounds great, but what do I do about it? And the advice it gives is: just take one word and use it to hammer your way through whatever obstructions lie between you and God. I guess the hammer isn’t a very elegant tool; it’s not a sophisticated instrument, but you can use it to batter your way through.

But there is actually a long tradition of this within Christianity, going way back. Take the Jesus Prayer, which was an important practice for the Desert Fathers and Mothers: ‘Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me, a sinner’. A little booklet I’ve used for many years argues that although you start off with the full form, through practice that becomes shorter and shorter until you’re left with maybe just the word ‘Lord’, or ‘Jesus’. So you become increasingly focused on that one thing – that one calling out to the one who’s calling you.

I don’t really go into this in the book, but I think behind this practice is a whole understanding of what it means to be called by name. There is an important tradition in the Eastern Church, and I suspect that it’s also there in the Islamic tradition, that God calls us into being as individual human beings – not just as examples of the human species. We are each given a name and He calls us by that name.

Peter: So would you relate this to the giving of a person’s name in Christian baptism?

George: Yes, absolutely. You are called into a relationship with God through the giving of a name, and God is revealed in a name. This is what is understood in the Christian tradition that’s focused on the name of Jesus. In the Jewish tradition, there’s the mysterious name of God that only the high priest is able to speak on the Day of Atonement. What this indicates is that the fulcrum on which the whole relationship between God and the world turns is in this exchange of names. But of course, the name is not just the articulated sound of certain vowels and consonants. It becomes manifest as a particular constellation of vowels and consonants, but what it is essentially is the address of one to the other. We call on God by name because we are called by name.

I think that this is a very basic thing that we see enacted in other contexts. If you have ever been in a serious medical situation and you being attended to by paramedics, they will ask people: What’s his name? And then they’ll say: George, stay with us. George, hang on. It’s so crucial in these emergency situations that the person attending has a name to call you by and sometimes we are literally brought back to life by being called by our name.

Such moments are the most intense of our lives, when we are brought to the most minimal focus of existence. To take a happier example: when people are very much in love, the moment when they speak their beloved’s name to them face to face for the first time is one of great intimacy. In many relationships, a couple will have a special name for each other that only they know. There is a closeness in that, and the relationship is sort of summed up in that exchange of names.

Peter: Does this have a resonance, do you think, to the Sufi practice of repeating particular names of God, which in my understanding has the aim of realising that quality in ourselves

George: Yes, I believe that there’s a great kinship. There’s something very persuasive, or productive, about the practice of uttering the names of God – which in the Islamic tradition, I know, find formal expression as ‘The Most Beautiful Names’, as in Al-Ghazali’s book The Ninety-Nine Beautiful Names of God.[4] The typical Western philosophical theologian will talk about the attributes of God as if He is a kind of substance. We ask: what is a tree? And we give the answer in terms of its attributes. It has roots; it has branches; it has leaves and produces seeds; and so on. Philosophers tend to talk about God in the same way. What are the attributes of God? Well, they are power; goodness; omniscience; etc. It is true that He is all these things. But thinking about God in terms of names puts you into a different zone – a much more existential zone because it puts you into that place of mutual calling.

Peter: A place of intimacy.

George: Yes, indeed.

Words and Silence

.

Jane: You said earlier that the act of praying itself educates us about the purpose of prayer – that we learn by doing. When we think of it in terms of mutual calling, does this imply that there is always a response to our call?

George: Well, the basic answer I could give is that it is actually the other way round; we call because we are called. The word ‘vocation’, which is much used in regard to the religious life, is often used in a fairly vague and even empty way. But in the French spiritual tradition, it embodies the idea that people are drawn to devotion. They often don’t really know why, and in the first instance it appears as what they call an ‘attrait’ – an attraction. It’s like the way we’re sometimes attracted to people, but we can’t say why; there’s just someone you want to be around. Some people just feel drawn to religion or spirituality; they just want it in their lives in some way. What they then discover as they go further into it is that they are actually being called to it. They are being called to a certain direction, to some task, to some orientation in life.

Jane: Beyond even the notion of the one word prayer is the idea that God, Reality, is actually beyond all qualifications and conceptualisation. So there is a point beyond which it is not possible to say anything at all. There is only silence. This is a truth that was famously articulated by Wittgenstein, who is one of the philosophers you discuss in the book. He maintained that there is a limit at which language fails and we are just faced with a mystery about which nothing can be said. But you argue for a more complex understanding of the relationship between words and silence, which, if I understand it correctly, is based on the understanding that language is given to us, like our existence. It is not something we have just made up.

George: Indeed, and there’s an interesting question here as to just what writings about mysticism Wittgenstein would have been aware of. In 1903, a German translation of key writings of Eckhart was published by Gustav Landauer, [5] who was also associated with a theorist of language, Fritz Mauthner, whose three-part work Contributions to a Critique of Language was published between 1901 and 1903.[6] So, questions about language, the mystical, and what is beyond language were very much around in Wittgenstein’s Vienna. We know that he was a man who deeply participated in the culture of his time, in its music and architecture and visual art, and so it is very likely that he was aware of Meister Eckhart. This is not something that philosophers on the whole have been very interested in, but I think there are some interesting points of cultural history to work on here.

For myself, I would not draw such a hard line between language and silence, and I suspect this would be true for all three Abrahamic religions – meaning Judaism, Christianity and Islam – which give primacy to the notion of ‘word’. After all, we have the great opening to St John’s Gospel: ‘In the beginning was the Word: the Word was with God and the Word was God’.[7]

In this context, we would have to say that silence is either the anticipation of the word – the waiting on the word – or the resonance or the reverberation of the word after it has been uttered. Insisting on the primacy of the word doesn’t mean that we have to be chatty all the time. Perhaps one only truly values the word when one gives it a lot of space – a lot of silence – so that it can be heard for what it truly is.

Peter: Like the silence that occurs at the end of a really great performance.

George: Yes. After a great concert – after the final chord, whether it’s a soft piano or a triple forte – there’s that moment before the applause comes. If people start applauding immediately, that’s a bad sign and it means they haven’t listened properly. But if you have that sort of moment – a hush – that’s the thing!

Jane: George, that’s a great note to end on. Thanks for speaking to us, and we wish you all the best with the book, which we very much enjoyed.

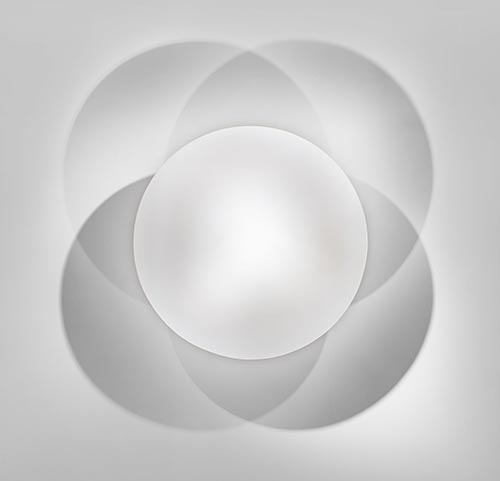

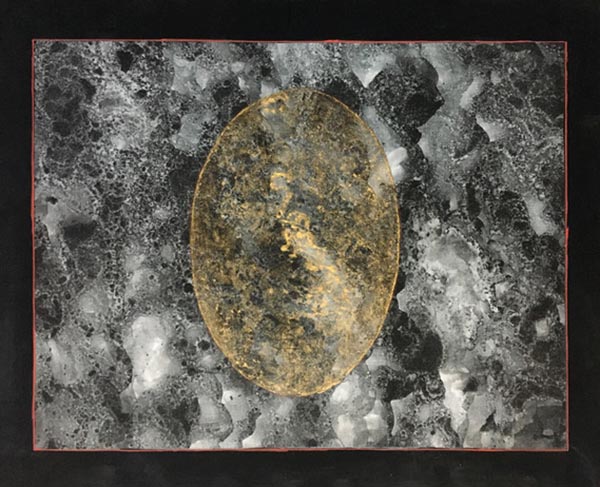

‘Shunyata-eka (1)’ by the Indian artist Abhay K. Featured in an exhibition at the Bihar Museum, India, 1–10 October 2024 entitled Shunyata | Emptiness. To read more, click here [/]. Image courtesy of Adhay K.

George gave the Beshara Lecture in 2017 entitled ‘Nothingness and Gratitude’. Click here [/] to see the video on YouTube, or visit the Beshara website [/] to see both the lecture and transcript.

Image Sources (click to open)

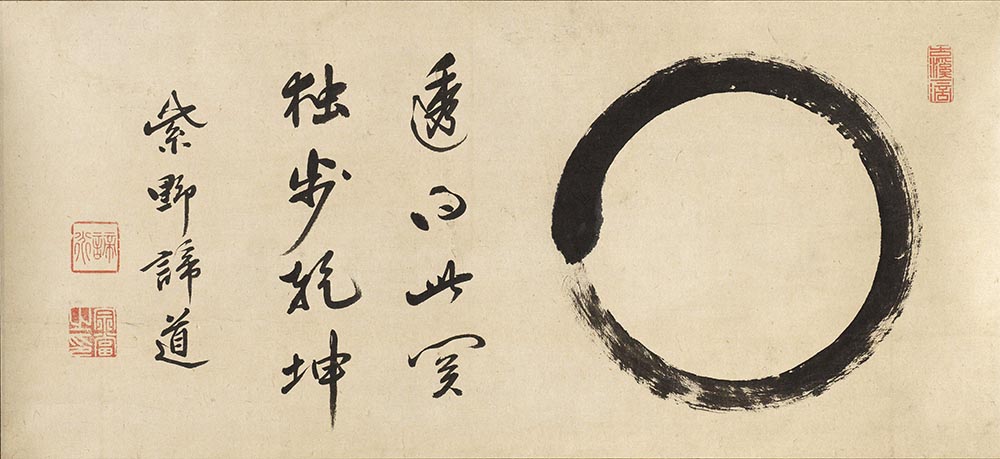

Banner: Japanese enso by Taidō Sō tō (1776 – 1836), 444th abbot of Daitoku-ji, one of 14 head temples of the Rinzai school of Zen Buddhism in Kyoto. An enso is a circle brushed in a single stroke representing the universe, perfection, emptiness and the enlightened mind. As the brush deposits ink, the stroke becomes scratchier, leaving the circle incomplete. The accompanying text is a Chinese poem: With a heart permeated with innocence The virtuous dragon walks alone. Image: Penta Springs Limited / Alamy Stock Photo.

Inset: George Pattison.

Our thanks for Sandra Hill for her help with the illustrations to this piece.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] GEORGE PATTISON, The Philosophy of Prayer (Fordham University Press, 2024).

[2] MICHEL FABER, Undying (Canongate Books, 2017).

[3] CHARLES UPTON, The Doorkeeper of the Heart (Pir Press, 2003) p. 47.

[4] Al-GHAZALI, The Ninety-Nine Beautiful Names of God, translated by D. Burrell and N. Daher (The Islamic Texts Society, 1992).

[5] GUSTAV LANDAUER, Skepsis und Mystik: Versuche im Anschluss an Mauthners Sprachkritik (E. Fleischel, 1903).

[6] FRITZ MAUTHNER, Beiträge zu einer Kritik der Sprache (J. G Cotta, 1901–3).

[7] The New Testament, John 1:1.

[8] From ROGER LIPSEY, Angelic Mistakes: The Art of Thomas Merton (Echo Point Books, 2006) p. 20.

[9] DOM SYLVESTER HOUEDARD, The Kiss: the Beshara talks of dom Sylvester houédard (Beshara Publications, 2023).

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

READERS’ COMMENTS

0 Comments