Metaphysics & Spirituality _|_ Issue 18, 2021

Father Bede Griffiths and

His New Vision of Reality

Adrian Rance-McGregor reviews the life of the pioneering 20th-century mystic, and the message of one of his most insightful books

Father Bede Griffiths and His New Vision of Reality

Adrian Rance-McGregor reviews the life of a pioneering 20th century mystic, and the message of one of his most insightful books

This article introduces readers to ‘A New Vision of Reality’ [1] by the Benedictine monk Bede Griffiths (1906–93), who is best known for his pioneering work in Southern India, bringing together the Christian and Hindu contemplative traditions. The book draws together important themes in Bede’s work to create a manifesto for how humanity can survive the modern social, economic and ecological crises and emerge into ‘a new earth and a new heaven’. Published in 1989, many of the insights in it have now become common currency, but they are, nevertheless, as pertinent to our situation today as they were forty years ago – maybe even more so. Adrian Rance-McGregor knew Bede from his early childhood; he helped establish the Bede Griffiths Sangha in the UK and the Bede Griffiths Charitable Trust, and has published books of letters by Bede to his friends.[2]

In December 1990 I visited Bede Griffiths in his small hut at the Saccidananda Ashram [/] in Shantivanam, Southern India, where he spent the last 25 years of his life. During our conversation he said to me, “Did I tell you I had a stroke earlier this year?” When I said that he had not, he went on and told me, “It was a wonderful experience!” Bede thought of his experience as a breakthrough to the feminine and the final integration of his personality. It was perhaps the culmination of a long life spent in prayer, meditation and a quest for the Absolute.

In December 1990 I visited Bede Griffiths in his small hut at the Saccidananda Ashram [/] in Shantivanam, Southern India, where he spent the last 25 years of his life. During our conversation he said to me, “Did I tell you I had a stroke earlier this year?” When I said that he had not, he went on and told me, “It was a wonderful experience!” Bede thought of his experience as a breakthrough to the feminine and the final integration of his personality. It was perhaps the culmination of a long life spent in prayer, meditation and a quest for the Absolute.

He recovered from this stroke, which left him with an enormous energy. For the next two years, before he had his final stroke, he travelled widely, giving talks to audiences in Europe, America, Australia and other parts of the world. These powerfully transmitted his urgent belief that if human society was to survive, the barriers between races and religions had to be broken down by drawing out the common truth and wisdom that lies behind all differences. As we shall see, Bede was convinced that the ‘perennial philosophy’ would be the basis on which the religions of the world would eventually find their true destinies, each one relating in love to the others.

The late Cardinal Basil Hume described Bede as a ‘mystic in touch with absolute beauty and love’. Bede knew that everything depends on love. He was clear that an experience of God known in the Vedas as advaita is an experience of love in which two become one without losing their distinct identities. In 1946 he wrote to my mother, Dorothy Rance, “I have a very definite idea of an immense power of love which is, as it were, circulating in the universe, and is gathered into the centre of our being.” [3] (For his own account of what he called ‘overwhelming love’ during his stroke in 1989, see video right or below.)

Experiences in Youth

Video: Bede Griffiths on the Nondual Mind. Duration: 3.26

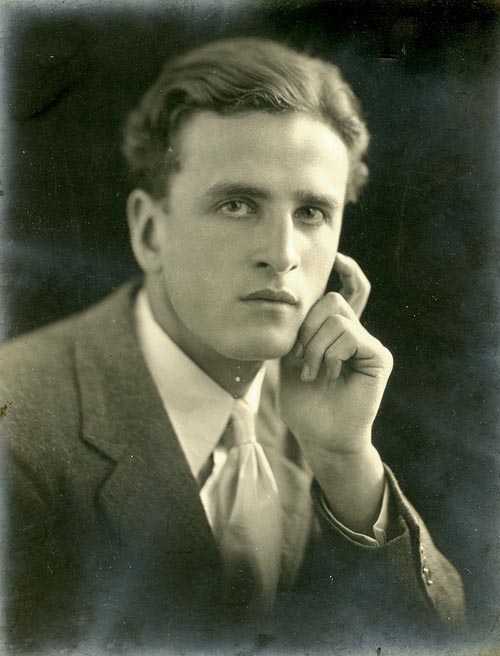

Bede’s understanding can be traced to an epiphany experience when he was at school, and which he described in his autobiography – or as he termed it, the account of his conversion – The Golden String published in 1954.

One day during my last term at school I walked out alone in the evening and heard the birds singing in that full chorus of song, which can only be heard at that time of the year at dawn or at sunset. I remember now the shock of surprise with which the sound broke on my ears. It seemed to me that I had never heard the birds singing before and I wondered whether they sang like this all the year round and I had never noticed it. As I walked on I came upon some hawthorn trees in full bloom and again I thought that I had never seen such a sight or experienced such sweetness before. If I had been brought suddenly among the trees of the Garden of Paradise and heard a choir of angels singing, I could not have been more surprised. I came then to where the sun was setting over the playing fields. A lark rose suddenly from the ground beside the tree by which I had been standing and poured out its song above my head, and then sank still singing to rest. Everything then grew still as the sunset faded and the veil of dusk began to cover the earth. I remember now the feeling of awe which came over me. I felt inclined to kneel on the ground, as though I had been standing in the presence of an angel; and I hardly dared to look on the face of the sky, because it seemed as though it was but a veil before the face of God.[4]

Bede was very open to experiences of the transcendent. Soon after he graduated from Magdalen College, Oxford in 1929, the young Alan Griffith (as he was then) went on a holiday to the Lake District. He later wrote:

I remember that I went out once alone among the hills, when a mist began to gather, and I felt myself alone in that mysterious solitude, as though I had been at the bottom of the sea, cut off from all the haunts of men; and once again the sense of that Presence which I had experienced at school took possession of me.[5]

In his autobiography The Golden String he also recounts an experience he had when working in a mission in the East end of London after a night spent in prayer:

I had come through the darkness into a world of light. That eternal truth and beauty which the sights and sounds of London threatened to banish from my sight was here the universal law. I heard its voice sounding in my ears. The very stones of the house seemed to be the living stones of a temple in which this song ascended. It was as though I had been given a new power of vision. Everything seemed to lose its hardness and rigidity and to become alive. When I looked at the crucifix on the wall, the figure on it seemed to be a living person; I felt that I was in the house of God. When I went outside, I found that the world about me no longer oppressed me as it had done. The hard casing of exterior reality seemed to have been broken through, and everything disclosed its inner being. The buses on the street seemed to have lost their solidity and to be glowing with light. I hardly felt the ground as I trod, and I think that I must have been in some danger of being run over. I was like a bird which has broken the shell of its egg and finds itself in a new world; like a child who has forced its way out of the womb and sees the light of day for the first time.[6]

Prinknash Abbey in Gloucestershire, UK, which Father Bede entered as a novice in 1933. Photograph: Krys Bailey [/] / Alamy Stock Photo

The Search for Simplicity

.

By the time Alan Griffiths left Magdalen College, Oxford (where his tutor was C.S. Lewis) he was driven by a desire to escape from, or at least go beyond, the complexities of modern technological civilisation, which he saw as immensely damaging. With his friends Martyn Skinner and Hugh Waterman the young men decided to rent a cottage in the village of Eastington in the Cotswolds and to undertake a life of utmost simplicity, sharing everything they had in common. Bede put it this way:

We were concerned with the very nature of our civilisation… and our purpose was to escape from industrialism altogether, from the whole system of mechanisation which we felt to be the cause of the trouble [in the organisation of civilised life].[7]

Here we have the start of a theme that was to stay with Bede throughout his life and which was to feature significantly in his New Vision of Reality published some 60 years later. Their life at Eastington was austere with no electricity or running water:

We used to kneel on the bare stone floor, not in the kitchen but out in the cold at the back of the house, and the words seemed to pierce the soul. Our life had already become extremely ascetic in many ways, not so much from any deliberate choice, but simply as the result of the way of life which we had adopted.[8]

The experiment in simple living only lasted a year. Alan eventually found his spiritual sanctuary and the satisfaction of his need for a life of simplicity when he joined the Benedictine community at Prinknash Priory in Gloucestershire in January 1933, where he was given the name Bede. His greatest difficulty was perhaps that the life of monastic simplicity was not nearly as simple as the life he had adopted over the previous years at Eastington or when living on his own. However, he fell in love with Prinknash and the monastic life:

I love every moment of the day, every stick and stone here, and every soul in the community, more than words can tell. And yet I find the life very hard in many ways, and I have a sense of the awful tragedy of life, which almost overwhelms me.[9]

Father Bede with the theologian and pioneer of interfaith dialogue Raimundo Pamikkar, at Shantivanam. Photograph: Oblates of Shantivanam [/] © Roland Roper

Falling in Love with India

.

Bede is now remembered by many as a saintly, white-bearded sage wearing the orange-coloured robes of the India sannyasi, a holy man who had renounced the world. His interest in India began with his discovery of the Indian scriptures, the Vedas, during his time as a monk at Prinknash Abbey. Subsequently he met and was profoundly influenced by Toni Sussmann, a Jungian analyst who introduced him to practices such as yoga. Then, while he was living at Pluscarden Priory in Scotland, Bede met Benedict Alapatt, an Indian monk seeking to develop a contemplative monastic life in India. Alapatt invited Bede to join him in this venture, with the result that Bede travelled to India in 1956. He later wrote:

For years I had been studying the Vedanta and had begun to realise its significance for the Church and the world. Now I was given the opportunity to go to the source of this tradition, to live in India and discover the secret of the wisdom of India. It was not merely the desire for new ideas which drew me to India, but the desire for a new way of life. I remember writing to a friend at the time: ‘I want to discover the other half of my soul’. I had begun to find that there was something lacking not only in the Western world but in the Western Church. We were living from one half of our soul, from the conscious, rational level, and we needed to discover the other half, the unconscious, intuitive dimension. I wanted to experience in my life the marriage of these two dimensions of human existence, the rational and intuitive, the conscious and unconscious, the masculine and feminine. I wanted to find the way to the marriage of East and West.[10]

Many of his friends were upset by Bede’s determination to go to India, feeling that they would lose a dear companion. In 1952, Bede wrote to his friend Toby Rance:

I am sorry that you don’t like the idea of my going to India… I am finding more and more that I have a psychological need of it. This corresponds in me to what I believe to be a universal human need – the need of the West with its rationalism, individualism and extroversion, to meet the deep, interior and contemplative spirit of the East. I don’t honestly think that there is any solution to the human problem until this takes place. At the same time I feel more and more the need to integrate Eastern thought into Catholicism. I feel that this is the great work of the future – perhaps of the next five hundred years – something comparable to the incorporation of Greek thought in the early centuries. I believe that this can only be done by means of the establishment of the monastic and strictly contemplative life.[11]

Bede’s initial attempt to establish a monastic life with Benedict Alapatt ended in failure, but soon he joined up with Francis Mathieu, a Belgian Cistercian monk, and in 1958 they established Kurisumala Ashram in Kerala. The monastery took the form of an Indian ashram in the Syrian rite. Ten years later, Bede moved to Shantivanam, an ashram of utmost simplicity first established in 1948 by the French priest Jules Monchanin. Over the next 25 years Bede sought to integrate Vedic philosophy and spirituality into his Catholic understanding, and he established the reputation of Shantivanam as a major centre for inter-religious dialogue.[12]

The chapel at the Saccidananda Ashram at Shantivanam in Tamil Nadu, Southern India. Photograph: https://www.shantivanamashram.com/about.php

The Problems of Modern Civilisation

.

Bede believed that modern technological civilisation was destroying humanity. It was this conviction that took him to Eastington after leaving university and it stayed with him throughout his life. My father, Toby Rance, who was converted to Catholicism by Bede, was an industrial chemist and a great enthusiast for the use of chemicals to improve agriculture – what he called chemiculture. Bede wrote a letter to him in 1941 that expressed his deep conviction that the industrialised world was creating harm and suffering:

For me the problem is how to find the proper place for industry and chemiculture within the framework of a complete human civilisation. To my mind our civilisation suffers from the over-development of science, industry and commerce at the expense of agriculture, craftsmanship and the fine arts.[13]

This conviction remained with him – and was to remain an ongoing subject of disagreement between Bede and my father – until the end of his life. In his book A New Vision of Reality which was published in 1989, Bede wrote:

The present system of technology has been built up on the basis of mechanistic sciences and it savagely and indiscriminately exploits the world of nature. This has produced the terrible situation in which we find ourselves with its material conveniences for a minority but with its disastrous consequences of global injustice and destruction. […]

The threat to the very existence of the earth has been so severe… we are ruining the earth with pollution of the air and water… that which has taken billions of years to grow is being destroyed in a matter of decades. All these disasters are signs of rebirth. The disaster is coming, but a new creation is coming out of the disaster, from death to resurrections… we are living in a world of tremendous drama, tragedy and hope.[14]

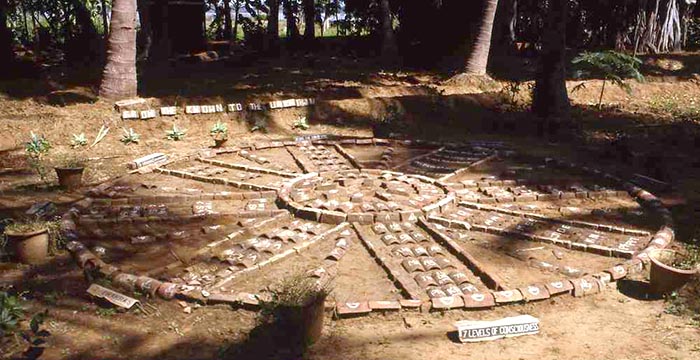

Mandala “From the known to the unknown”, at the Saccidananda Ashram at Shantivanam in Tamil Nadu. Photograph: D. Gardiner, courtesy of Adrian Rance

A New Vision

.

A New Vision of Reality is a book that brings together many themes in Bede’s spiritual development into a unified manifesto for how humanity can escape from the social, political and environmental difficulties of the present age. Bede looks forward and sees the emergence of a new era that will grow out of the collapse of the present world order. He shows how so many things point towards this new era as an inevitable consequence of human evolution. All the world’s major religious traditions contain within them the seeds of an integrated, non-dual experience of reality. Modern science and the growth of new levels of consciousness make it inevitable.

The book was actually dictated onto tapes which were then transcribed and edited by Professor Felicity Edwards of Rhodes University in South Africa. It is the culmination of a long search to find meaning in the New Testament vision of a ‘new heaven and new earth’ (Revelation: 21) which goes back at least to Bede’s time in Pluscarden Priory in Scotland. There, in 1952, he started writing a book on ‘The New Creation’ which was to be a study of the seven sacraments of the Church – a far cry from the book he eventually created in India thirty-seven years later. The essence of Bede’s ‘vision’ is that the present world order is based on a mechanistic view of the universe, and a materialistic and individualistic view of society will collapse. But out of the collapse will emerge a new era in which human consciousness will develop and become more and more open to the transcendent order. This will then shape and form how humanity lives together and learns to love the world, the universe and the cosmos. It is a vision rooted in spiritual, metaphysical, psychological and scientific understanding but which has an application in everyday life that is practical and grounded in the day-to-day reality of people’s lives.

Bede saw that the problems of materialism, individualism and exploitation of the natural environment arise in great part from a loss of what Aldous Huxley called the ‘perennial philosophy’. This is the philosophy which has underpinned all the great religious movements of the world, forming the basis of the religious understanding of mankind from the earliest pre-historic times and still found in the religious beliefs of all indigenous peoples. Experience of this was lost at the Renaissance in Europe, to be replaced by a vision of the world as solely physical and material after the scientific discoveries of the Age of Enlightenment.

A New Vision of Reality grew out of Bede’s encounter with new scientific paradigms that seem to make it possible to re-integrate scientific understanding once more in a vision of the universe that brings together the physical, the psychological and the spiritual. This integration, together with an evolution of human consciousness to become more open to the ‘supraconscious’ – to be in touch with the transcendent reality – makes it possible to move towards a new world, the ‘new heaven and the new earth’ of the early Christian experience.

Bede lays the blame (if that is the right word) for the present immersion in an individualistic and materialistic way of life on the mechanistic view of creation with which scientists such as Isaac Newton and philosophers such as Descartes laid the foundations for the Age of Enlightenment. Although both of these giants of Western intellectual achievement were Christian with a belief in God, their work led to a paradigm which broke apart the medieval understanding in which the material, the psychic and the spiritual worlds were integrated into one dynamic whole.

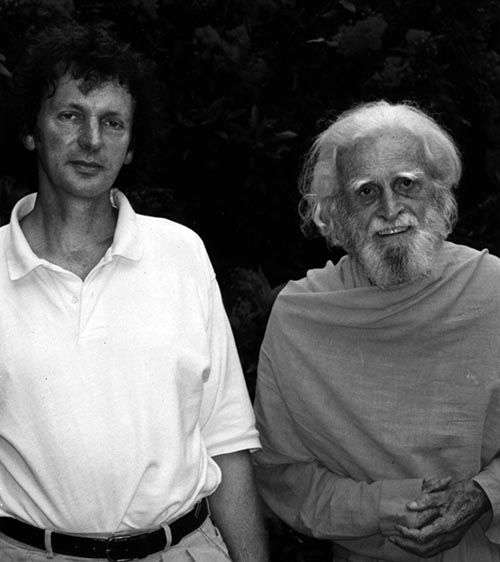

Father Bede with Rupert Sheldrake, who spent eighteen months at Shantivanam in the late 1970s whilst he was writing his seminal work ‘A New Science of Life’. Photograph: courtesy Adrian Rance

Bede’s project was nothing less than the reversal of three decades of materialistic thought to find again an integrated view of reality. The breakthrough came when he encountered the work of the physicist David Bohm and his theory of the implicate order [15] (see also our interview with Bohm) and the Tao of Physics by Fritjof Capra.[16] Here he discovered new scientific paradigms that created a situation in which a universal and integrated vision of the world could incorporate modern scientific thinking. In this new scientific understanding, the dualistic paradigm of the cosmos is replaced by a view of the universe being a web of interdependent relationships. Bede believed that this heralds an era in which matter and consciousness are seen to be aspects of the same reality.

In psychology, the modern understanding was first delineated by Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, both of whom focussed their research on understanding the unconscious mind. They proposed that the repressed unconscious has a profound effect on the mental consciousness (that which we are aware of) and behaviour. Bede was also very influenced by the work of the American philosopher Ken Wilber [17] who identifies six levels of consciousness: the ‘lowest’ he calls oceanic consciousness, the primeval consciousness in which the human being is totally immersed in nature and is one with the universe. The next stage is that of mental consciousness in which the human being becomes aware of a self, the awareness of an ego; this is the level at which most people live, a level at which everything is centred upon the egoic self. There then follows a level of psychic consciousness which incorporates what we now call parapsychology and, in India, siddhi powers and the powers of the shaman, or even the world of ideas, the eternal forms envisaged by Plato. At the final state of supreme consciousness, a person ‘realises’ the whole of creation, the supreme reality, the godhead. As Bede puts it in A New Vision of Reality:

And that is the ultimate goal of life, to reach that total unity where we experience the whole creation and the whole humanity, reintegrated in the supreme consciousness, in the One, which is pure being, pure knowledge and pure bliss, saccidananda.[18]

A third strand of Bede’s encounter with modern science was through the biologist Rupert Sheldrake whose work demonstrated the connectedness of plants and animals through what he called ‘morphic resonance’ [19] (see also our interview with Sheldrake).

Bede’s grave (right) at Saccidananda Ashram. Photograph: Richard Twinch

The Way Forward

.

Bede’s vision was that the world is entering a new era, an era in which the evolution of human consciousness will converge on an ultimate reality – a Supreme Being – when all that which tends to fragment humanity will tend towards unity. He was clear that things are happening now and forces are coming together which will eventually allow this ‘new heaven and the new earth’ to manifest. Then rational scientific understanding and spiritual understanding will converge as the universe and humanity return to the divine unity in which creation is restored and renewed. In his words: “in this new Age there will be a sense of communion with an encompassing reality which will replace mankind’s attempts to dominate the world.” [20]

Bede predicted that new technologies and the renewal of crafts will allow people to live in harmony with nature and each other, and new forms of community shunning the big cities will emerge. In the sphere of religion there will be a return to the perennial philosophy, meaning that all the major religions must undergo reformation, acknowledging the wisdom of each other and seeing that all religions are related and interdependent. Openness to the feminine will change patriarchal structures.

Bede was convinced that the key to this transformation of humanity is meditation, which leads to going beyond the levels of ordinary physical and psychological awareness – but not rejecting them – into a transcendent consciousness. The ordinary rational mind has no access to this realm, which can only be perceived by intuition. It is only by going beyond ideas, images and the whole rational mind that a person can enter into an experience of their true humanity. In this way, a transformation of the individual can take place which in turn will lead to the transformation of the world. [21]

Bede’s understanding of the importance of meditation in the creation of a new earth and a new heaven is seen in the following extract from The New Creation in Christ, based on talks he gave in 1991 in Indiana:

The rational mind based on the experiences of the senses is inherently dualistic. It sees everything in terms of opposites, mind and matter, subject and object, truth and error, right and wrong. But always beyond the dualism of the mind is the unity of the spirit. Meditation takes us beyond the dualities to the unified spirit… it is only through meditation that we get beyond this duality. We are called to recover unity beyond duality as our birthright, and it is this alone which can answer the deepest needs of the world today… We are all being called to open our hearts to the nondual mystery which is the mystery of love revealed in the Trinity… it is to the experience of the eternal wisdom communicated in the love of the Holy Spirit that our meditation should lead us.[22]

Bede always took the long-term view and concluded his book A New Vision of Reality with the words:

This is a task for the coming centuries as the present world order breaks down and a new world order emerges from the ashes of the old.[23]

The present-day catastrophes of Covid-19 and climate change dramatically confirm Bede’s prescient analysis of the challenges facing humanity. One cannot help but wonder whether the changes he foresaw will come about sooner rather than later.

Video: Interiew with Sam Keen. Duration: 35.38

To hear Bede himself talk about some of these ideas, see the video interview (right or below) with Sam Keen, which took place during his visit to America in 1990.

A wealth of further information and material is available on the Bede Griffiths Trust website www.bedegriffiths.com

Adrian Rance-McGregor knew Father Bede from his early childhood. He helped establish the Bede Griffiths Sangha in the UK and the Bede Griffiths Charitable Trust, and has published books of Bede’s letters, including ‘Falling in Love with India’ (2006) and ‘On Friendship‘ (2014). He is currently engaged in extending the Bede Griffiths Sangha website to include an archive of all Bede’s talks and published articles. Photograph: Adrian (right) at Shantivanam, by Richard Twinch

Image Sources (click to close)

Banner Image: Father Bede performing a ceremony at the Saccidananda Ashram in Shantivanam, Tamal Nadu, Southern India. Photograph: https://www.shantivanamashram.com

Inset: Statues of the holy family at the Saccidananda Ashram. Photograph: Richard Twinch.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] BEDE GRIFFITHS, A New Vision of Reality (Collins, 1989).

[2] ADRIAN RANCE (Ed)

Falling in Love with India (Shantivanam Ashram, 2006).

On Friendship: The Letters of Bede Griffiths to Richard Rumbold (Templegate Publishers, 2014).

[3] ADRIAN RANCE (Ed), Letters from Bede Griffiths to Toby and Dorothy Rance (Privately Printed, 2020). The original letters are in the Bede Griffiths Archive, Douai Abbey, Woolhampton, Berks.

[4] BEDE GRIFFITHS, The Golden String (Harvill Press, 1954), p.9.

[5] Ibid., p.37.

[6] Ibid., p.96.

[7] Ibid., p.61.

[8] Ibid., p.82.

[9] Letter from Bede Griffiths to Martyn Skinner, October 1937, unpublished. The original is in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

[10] BEDE GRIFFITHS, The Marriage of East and West (Collins, 1982), pp. 7–8.

[11] Letter Bede Griffiths to Toby Rance, October, 1952. Bede Griffiths archive, Douai Abbey.

[12] SHIRLEY DU BOULAY, Beyond the Darkness: A Biography of Bede Griffiths (Rider, 1998).

[13] Letter Bede Griffiths to Toby Rance, November 1941. Bede Griffiths archive Douai Abbey

[14] BEDE GRIFFITHS, A New Vision of Reality, pp.276 ff.

[15] See for example DAVID BOHM, Wholeness and the Implicate Order (Routledge, 1983: 2003).

[16] FRITJOF CAPRA, Tao of Physics (1975: HarperCollins, 1992).

[17] See for example KEN WILBER, The Spectrum of Consciousness (1977: Quest Books, 1993).

[18] BEDE GRIFFITHS, A New Vision of Reality.

[19] See for example RUPERT SHELDRAKE, A New Science of Life (1981: Icon Books, 2009).

[20] BEDE GRIFFITHS, A New Vision of Reality, pp.282.

[21] See particularly ‘On Contemplative Prayer’: A Talk given at Osage Monastery, U.S.A., October 1991. https://bedegriffithssangha.org.uk/contemplation/

[22] BEDE GRIFFITHS, The New Creation in Christ (Darton, Longman, Todd, 1992).

[23] BEDE GRIFFITHS, A New Vision of Reality, pp.296.

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

Video: Bede Griffiths on the Nondual Mind. Duration: 3.26

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

Video: Interiew with Sam Keen. Duration: 35.38

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

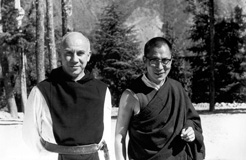

The Engaged Contemplative Spirituality of Thomas Merton

Jim Griffin reviews the life of the 20th century monk who did so much to revive the Christian practice of meditation

Towards a Deeper Spirituality

The Reverend Peter Dewey looks back on a lifetime working with interfaith projects

Infinite Potential: The Life & Ideas of David Bohm

Film director Paul Howard talks about his new film on the life and ideas of the physicist and philosopher David Bohm

Sheldrake: Memory, Habits and Wholeness

Biologist Rupert Sheldrake challenges the dogmas of conventional science, and explains how recent research supports his alternative theory of morphic resonance

READERS’ COMMENTS

Excellent, interesting and informative article on Father Bede Griffiths . Thank you so very much.

An amazing article about an amazing man who was one of the great luminaries of our age . The marriage of east and west is deeply fused now .

The collapse of our modern monstrously materialistic world which father Bede foresaw ,which has been prophesised for thousand of years .Is now in full swing and about to climax and from it the NEW HEAVEN AND A NEW EARTH and a transformed humanity will emerge .THE TIME IS NOW 🌈🙏