Finance & Global Affairs _|_ Issue 14, 2019

The Universal Language of Football

Kawther Luay explains how the Homeless World Cup is giving hope to thousands of people all over the world, and talks to its co-founder, Mel Young

The Universal Language of Football

Kawther Luay on how the Homeless World Cup is giving hope to young people all over the world, and talks to its co-founder Mel Young

Since 2001, the Homeless World Cup has been bringing together disadvantaged people from all over the world to compete in an annual football tournament. This year, the event took place in Cardiff, where more than 500 players, many with a background of addiction, abuse or persecution, gathered with thousands of spectators to celebrate the power of sport to generate hope and goodwill. Kawther Luay attended, and talked to Mel Young, one of the founders, about the thinking behind the project and the secret of its remarkable success.

The Homeless World Cup [/] began with a conversation between two old friends over a beer. Mel Young and Harald Schmied had just emerged from the 2001 annual conference of the International Network of Street Papers in Graz, Austria. It was a rewarding and enthralling gathering of editors, founders and directors. They were, however, concerned that no one who had experienced homelessness had attended. Mel remembers: “By the end of the night, we had invented the Homeless World Cup, where teams from all over the world could represent their country in a week-long street soccer tournament. It was a lively and animated conversation and we both imagined a colourful football competition which would change peoples’ lives.”

The Homeless World Cup [/] began with a conversation between two old friends over a beer. Mel Young and Harald Schmied had just emerged from the 2001 annual conference of the International Network of Street Papers in Graz, Austria. It was a rewarding and enthralling gathering of editors, founders and directors. They were, however, concerned that no one who had experienced homelessness had attended. Mel remembers: “By the end of the night, we had invented the Homeless World Cup, where teams from all over the world could represent their country in a week-long street soccer tournament. It was a lively and animated conversation and we both imagined a colourful football competition which would change peoples’ lives.”

Eighteen months later, in 2003, they hosted the first tournament in Graz. With each successive year since then, the Homeless World Cup has grown in scale and spirit, with the Welsh capital Cardiff being the most recent host in August 2019. This year’s event brought together over 500 players representing more than 50 countries, and spectator crowds in Cardiff’s Bute Park exceeded 80,000 people, with millions more watching online. Since its inception, more than one million homeless people worldwide have participated, 80% of whom have since changed their lives significantly because of their involvement.

It is estimated that 150 million people are homeless worldwide. Habitat for Humanity estimated in 2015 that 1.6 billion people around the world were living in ‘inadequate shelter’, and the number has without doubt grown since then. In the face of a problem of this scale, I asked Mel why football is such a powerful tool to combat this situation? He replied:

Homelessness is a huge problem, and when you see these sorts of figures, you can get completely numbed by them and don’t know what to do. We use football because actually it’s very simple. First of all, it’s easy for people to engage with; you can just go to them in the street and ask if they want to play. You might be good, you might not be very good, you can play two-a-side or five-a-side – and it doesn’t matter. You can play anywhere and with anyone.

The other reason is that football is an international ‘language’ which is very easy to speak. Other people can understand it as well – the people watching and the media. We get a lot of media attention now, but for us to get any kind of coverage for homelessness before we took on the football was very difficult because people just weren’t interested. Football is also a language that levels the playing field; people can connect with others they wouldn’t have otherwise. I have seen, for example, one of the richest people in the world talking with some homeless people about the football. Now, I know for certain, if it hadn’t been for that tournament, that conversation would not have been possible.

The Opening Ceremony in Glasgow, 2016. Photograph: courtesy of the Homeless World Cup

Participants

.

Players are recruited through a network of over 70 street football partners [/] who are aiming to make football accessible to the most marginalised communities. Word is put out through posters, street papers and hostels. To make it into a team, a person is considered for their sincerity of commitment and personal attitude more than for their sporting ability. This forces homeless people to overcome their greatest barrier – isolation – which hinders their ability to communicate, share and work in a team. Teammates are held responsible for attending training sessions on time, prepared and sober, thereby establishing structure in chaotic lives and forming trusting relationships. The sense of empowerment and belonging that comes from being a part of something bigger than themselves sows a seed which has the potential to change peoples’ lives.

Marius Pazemechas, referee. Photograph: Daniel Lipinski / Soda-Visual [/], courtesy of the Homeless World Cup

This model of engagement has been shown to be effective even with people who have not responded to other forms of intervention. Lithuanian street soccer goalkeeper-turned-coach, for instance, has spoken about his struggles with alcohol addiction: “I tried five times to get sober. My wife wanted to divorce me; she told me maybe 100 times that she wanted to divorce. I always thought alcohol was not the main problem for me; it was the boss, my wife, the other people. But losing my family, my job, my house, being on the street, being homeless – I understood that it was my last opportunity, next step will be that I die.”

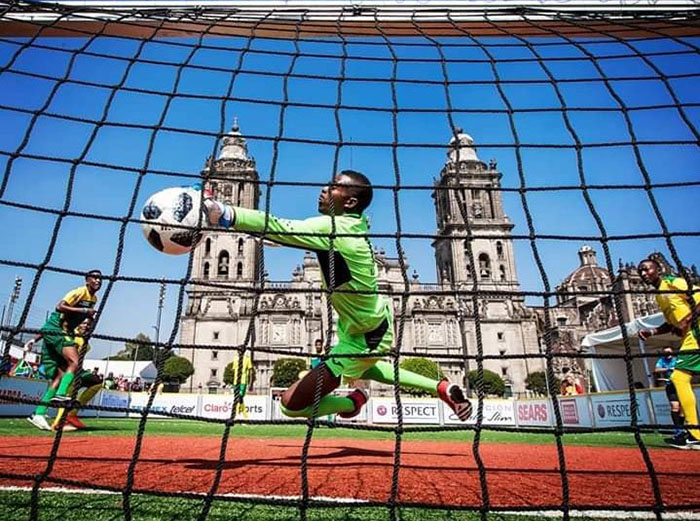

Football was the turning point for him. He discovered the Lithuanian football team, which supported addicts, and started playing with them in 2012 after his first year without alcohol. “Mexico was my first Homeless World Cup. I knew I wanted to come every year, so I became the team’s coach. I have not been drinking ’til today and have been with the team for six years.”

With Lithuania’s population having the largest percentage of alcoholics per capita, Pazemechas felt motivated by the impact the tournament had on him to give back to his community: “After the Homeless World Cup, back in Lithuania I started college, studying social work. I graduated when I was 50. I started to work in shelters with homeless people, and now I am working with people with addiction.”

Players only get to compete in a Homeless World Cup once. For those who want to stay involved long-term, the Homeless World Cup has developed an International Referee Programme. By training players to professional referee standards, they not only get to take part in future tournaments, but also to join local partners in their communities back home. Some go on to become professional FIFA referees, establishing careers on the pitch that mark their transformation. It also means that over a span of 16 years with tournaments across the globe, an accumulation of volunteers and players have formed a dedicated group of referees.

Adil Leite, who umpired the final in Cardiff. Photograph: Paul Bence / Soda-Visual [/], courtesy of the Homeless World Cup

One of these ex-players, Adil Leite [/] – the referee selected to officiate at the 2019 mens final between Chile and Mexico – has spoken of his elation as he took to the stadium with the teams. “I don’t know how to describe this because I was a player in Poznan [in 2013]. Now I am refereeing the final!”. The experience of representing his adopted nation in Poland shaped his new life and gave him the opportunity to continue with the sport, despite his reservations about his aptitude to referee: “I’m a quiet and relaxed person. I’m not a ‘referee’ type of person. But I love football and I wanted the chance to continue with it, so when they gave me a chance to come to Glasgow [in 2016] to be a referee of course I said yes. I got involved more to help others who were struggling and who went through the same situations that I had.”

Homeless World Cup in Glasgow, 2016. Photograph: Anita Milas [/]

The Rules of the Game

.

Homeless World Cup matches are 14 minutes long, with two halves of seven minutes each, and a one minute interval in between. They take place on a small sized pitch – 22 metres long by 16 metres wide – roughly a fifth of the length of a standard pitch. The goal size is only 1.3 metres in height, with a penalty radius of four metres. There are three outfield players and a goalkeeper on each team, and at least one player must remain in the opposition half of play. This makes for a thrilling game. The goals come fast and with playful flair, in some matches teams averaging one every 30 seconds.

When skilled teams play against each other, the tension of play is in their tightly stitched and rigorous defence. Behind the players is a basketball-style scoreboard with the digital time counting back, encouraging the crowds to chant the final 10 second countdown, often spurring players to chance a shot and score in the last second. I ask Mel whether the unique form of the game is designed to make it more accessible?

Absolutely. We selected small courts quite deliberately, because getting homeless guys to play 11-a-side is too much of a challenge. With smaller pitches, we can go to where the homeless are and play on any street. Also, people are not necessarily very fit, so we have shortened the game time.

We’ve invented this game around the homeless, but if you look at it from a purely sports point of view, it’s very exciting to watch. With some of the games, the standard of football here is phenomenal.

I confirm that I myself find it totally dynamic and exciting and thrilling (see video right or below to see a match from this year’s event). I was on the edge of my seat during most of the games, whereas I find mainstream football incredibly boring. He tells me that this is a common experience:

A lot of people come here who don’t like football. My wife hates football. But she loves this. There’s something here about the atmosphere that makes it compelling. I think it’s because, for the players, this is their moment. They are only allowed to come once to a tournament, so this is it. Imagine yourself: if you had one moment to shine in your life, what are you going to be like? You’re going to give off something, and it rubs off on the crowd and creates an amazing, intense atmosphere.

Video: Semi-final 2019 Mexico v Portugal. Duration: 24.22 minutes

Although it is a competitive sporting event, the structure of the tournament and the particular emphasis on fair play ensures that every team plays until the last day. One thing I noticed is that, although there is of course a desire among teams to win, over-riding that there is a sense of inclusivity, connection and friendship. Mel agrees:

The players do want to win the games, so the tournament is competitive. But a minute after the game, they’ve forgotten whether they’ve won or not. One of the reasons they come together here is that they all come from the same background. They understand each other and see how homelessness manifests slightly differently in different parts of the world. They’ve all come from the same position and they respect one another. To me, that’s how sports should be played.

One day it started raining and all the players took shelter under a large tent; then they put on some music and they were all dancing together. I thought: this is what humanity should be like! They can’t speak the same language, they all come from incredibly challenging and poor backgrounds, and here they are, dancing. Sometimes I imagine what it would be like if these people were ruling the world. They should be running the United Nations.

Award ceremony in Glasgow, 2016. Photograph: Anita Milas [/]

Difficult Backgrounds

”“.

The opportunity to travel and meet supportive people who are facing similar challenges is hugely transformational for the players. Many of them are also proud to be playing for their country. Fahrudin Muminovic [/], representing Bosnia and Herzegovina in Cardiff, has described how: “when I’m playing football with my mates or at this tournament, I feel like I’m part of something bigger. One of my greatest wishes in life has been to represent my country in something, so it’s a great honour to wear its flag on my chest. It is almost as important to me as having a house.”

Fahrudin’s homelessness is the result of being a survivor of the devastating Srebrenica massacre in 1995 [/]. At the age of seven, he watched as over 150 people from his village were killed, including his father. For most of his life, he has lived in refugee camps as a protected witness, giving evidence in The Hague to the International Court of Justice. “Most of my testimony was given anonymously, but a few years ago my story became public and I am proud to say I was that boy who survived.” In Cardiff, he was proud to reveal his identity and speak openly about his story.

Fahrudin Muminovic of the Bosnia and Herzegovina team, Cardiff 2019. Photograph: Daniel Lipinski / Soda-Visual [/], courtesy of the Homeless World Cup

It seems to me that there is a bittersweet irony in a person representing a country whose government has failed them. I wonder what Mel thinks about this.

I’ve always thought there is a contradiction here, because they sing the national anthem with such pride. They shout it out. They’re better than the professionals in terms of their commitment to their country and their commitment to the team. Yet, you’re right: at the same time they have a lot to be very angry with their government about. I think their maturity and determination is a very powerful thing. If they want to represent their country, they have every right to do so. If they don’t want to, we would also understand.

Since its inception in 2003, the Homeless World Cup encountered particular resistance with female engagement. In the beginning, only 10% of women were prepared to participate in the games, so there were a few mixed teams. By partnering with international sports organisations such as Slum Soccer [/] and Women Win [/], which implement sports programming in humanitarian settings, within a few years the Homeless World Cup was able to include women-only teams.

In many parts of the world, there are huge barriers facing young girls who dream of playing football, none greater than those faced by the remarkably determined Sujata [/], whose long road to Cardiff began from a small village outside Darjeeling. She has spoken of how the cultural restrictions placed on her catalysed her early independence: “It was really hard to convince my dad – he wanted me to be good at my studies, but I loved to play. He used to come to the piece of ground where I would play and shout: “What are you doing, there is work to do, don’t… don’t… don’t…” many times. So I moved three hours from my home. I had to leave my family – had to live in a hostel and got work in a bazaar and other jobs.”

Her time in a temporary hostel (residents of which are considered to be homeless) put her in touch with Slum Soccer, who trialled her for the international Indian team. She subsequently made her place alongside women from all over the country.“I feel life is changing for women in India, especially through football. Some women who have been here before have gone on to be referees, or to coach. I feel this is time to change, whatever the struggle might be.”

Sujata of the Indian team, Cardiff 2019. Photograph: Mile 44 [/], courtesy of the Homeless World Cup

Effective Investment

.

Countries that apply to host the Homeless World Cup are evaluated on a number of criteria which include an assurance to provide visas for all participating nations, a high profile venue and adequate accommodation. After the 2019 Cardiff tournament, the organisers announced the first formal host-city bidding process, and were delighted to receive a record-breaking 57 expressions of interest.

To put on an event like the Homeless World Cup incurs huge financial costs, and some critics deem a tournament of this scale to be extravagant, claiming that the money would be better spent by pouring it into the homelessness issue directly? Mel retaliates by telling me that he believes that the money is actually wisely spent.

People might say: “Why don’t you build houses instead?”. Yes: we could take the money we’ve raised here and build some houses, but not very many. And anyway the problem isn’t about housing necessarily, it’s about homelessness. There’s a difference between houselessness and homelessness. What we do is something else. Every year, 80% of these players will change their lives forever. The cost of a person being homeless in the US is about $ 40,000 per annum. We have 500 tournament players, over 100,000 people involved in our programmes all over the world, so you can work out how much this programme is saving world society. So in terms of the finances, this little investment is creating huge savings – quite apart from the issue of us wanting to change people’s lives.

You have to invest properly if you’re serious about ending an issue of this scale. You can spend a lot of money on managing homelessness, meaning that when people are hungry and homeless, you can give them soup and shelter. But are you actually solving the problem? No, you’re not. We have to figure out a way to live in a society where no one becomes homeless in the first place, and consider how to solve the problem in the long term.

So, I suggest, the question is not so much how do we pick up the pieces of those that have fallen through the gaps, but how do we seal up those gaps altogether?

Yes. There are issues which I would deem to be systemic failures in terms of the social organisation that we’ve got. We have to decide, as people and members of society, how we want to live. Are we going to live in a world which is greedy, selfish and materialistic and that destroys the planet? Or are we actually going to respect the planet, our environment and the human beings that live in it? Sometimes when we’re faced with big numbers and statistics, it makes us feel kind of frozen – we don’t know what to do, it’s too much. My line always is: it’s about people, and they are individuals. You can talk to them, start a conversation. It’s about the values that we have at the base of society.

There was an American study in which they asked people walking along a particular street every day what they had seen over the past month. The responses were that they saw a Mercedes, an amazing dress in a shop window, that sort of thing. Only about 10% of them said they saw a homeless person on the ground. Some people in our societies have become invisible, and it’s terrible that people have become immune to homelessness. No one should be on the street in the first place. We should be appalled! We should be talking to them and finding out why they’re there and what we can do to help.

Bhim Dhungana of the Finnish team which won the Beddgelert Cup in Cardiff, 2019. Photograph: Daniel Lipinski / Soda-Visual [/], courtesy of the Homeless World Cup

Into the Future

.

On the final day of the Cardiff games during the handing-over ceremony, it was announced that the 18th Homeless World Cup would take place in Tampere, Finland, in late June 2020 (see video right or below). The transformative impact a tournament has on a host-city is articulated through a highly structured and targeted bidding process that requires long-term commitment, organisational planning and a promise to not only deliver a once-in-a-lifetime event, but to continue to tackle homelessness long past the time of the final whistle.

Video: Homeless World Cup 2020. Duration: 1.07 minutes

Finland’s unique approach to solving homelessness shows great promise, with the government committing itself to abolish it altogether in the coming years. Since 2010, homelessness has fallen by 35% in Finland, whilst across all EU countries the figures have steadily increased, with housing problems reaching crisis point in some places.

I suggest to Mel that what is unique about the Homeless World Cup is that it is essentially working towards its own non-existence. He agrees:

Yes, I often say that what we’re trying to do is to put ourselves out of business. And you know, people kind of laugh, but actually what we’re really, really trying to do is exactly that – put ourselves out of business. It’s absurd in a way that we have a football competition whereby we tackle homelessness when there really shouldn’t be any homelessness to begin with.

More than one million people worldwide have had their lives positively impacted by the Homeless World Cup and its partner programmes. While the process of transforming lives is non-linear and difficult to quantify, there are countless moving stories from players expressing gratitude for finding dignity and self-worth despite their challenging circumstances, perceived failures and dark isolation. Many go on to become professional footballers, referees, coaches, and to rekindle long lost connections with their families and friends back home. By showing the human face of homelessness, this empathetic movement challenges public perceptions and the issues that surround it.

To find out more about the Homeless World Cup, visit their official website [/].

For an independent evaluation of the social value of their work, see the Prosocial Valuation document [/] for 2016.

Cartoon by Simon Blackwood

Image Sources (click to close)

Banner picture: The Mexican women’s team win the final at Cardiff in 2019. Photograph: Courtesy of Homeless World Cup.

First inset: Mel Young at the opening of the Cardiff Games. Photograph: Anita Milas [/].

Email this page to a friend

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

Video: Semi-final 2019 Mexico v Portugal. Duration: 24.22 minutes

Video: Homeless World Cup 2020. Duration: 1.07 minutes

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Narratives for a Unified World

Andrew Singer talks about the vision behind the literary journal Trafika Europe

Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama

Jane Carroll visits a new memorial which aims to heal a dark period of American history

Reconciliation and Justice in Australia

How a nation is trying to heal the wounds of its colonial past and reconcile with its indigenous people

The Revival of the Commons

Political strategist David Bollier explains how a new economic/cultural paradigm is challenging the increasing ‘enclosure’ of wealth and human creativity

READERS’ COMMENTS

Uplifting article, thanks for it. I do hope they succeed in ‘putting themselves out of business’.

Although Utopian in aims, the sentiment is very real.

What a language for me to learn.

Just released on Netflix, movie ‘Beautiful Game’, a drama based around a Homeless World Cup, with Bill Nighy definitely worth a watch.