Finance & Global Affairs _|_ Issue 28, 2025

Rolling Out the Doughnut

We talk to Leonora Grcheva of the Doughnut Economics Action Lab about how Kate Raworth’s innovative economic theory is being translated into sustainable practice in cities and regions across the world

Rolling Out the Doughnut

We talk to Leonora Grcheva of the Doughnut Economics Action Lab about how Kate Raworth’s innovative economic theory is being translated into practice in cities and regions across the world

Leonora Grcheva is the Cities and Region lead at the Doughnut Economic Action Lab (DEAL), working with people from all over the world to explore new ways of envisioning their local communities. The project draws upon the ideas of the British economist Kate Raworth, who, in her 2017 book Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist, [1] proposed a new economic theory which addresses the question: “How can we ensure that every human being has the resources they need to meet their human rights – but that collectively we do it within the means of this planet?” The book became an international best-seller and generated wide-spread interest; we did an article on it ourselves in the magazine. (Click here) The work of the Action Lab is to explore how the theory can be put into practice, and Leonora is currently working with about 50 cities and regions across the world in ‘rolling out the doughnut’ to explore innovative ways of living and working together. Jane Clark and Peter Huitson talked to her by Zoom.

In 2012, British economist Kate Raworth proposed a new economic theory in response to the global situation we find ourselves in in the 21st century. Dubbed ‘Doughnut Economics’, it presented a powerful visual model of sustainable development aimed at addressing the question:

How can we ensure that every human being has the resources they need to meet their human rights – but that collectively we do it within the means of this planet?

This idea was originally presented as an Oxfam Discussion Paper when Kate was working for the organisation. In 2017, she fleshed out her vision in a book entitled Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist.[1] This became an international best-seller and spawned wide-ranging discussion in circles as diverse as the Vatican, the UN General Assembly and Extinction Rebellion. We did an article on it ourselves in Beshara Magazine, seeing it as a hopeful move towards a different way of conceiving not only our economy and society, but also ourselves, allowing us to escape from identification with what Raworth calls homo economicus – the idea that we are defined by our roles as workers and consumers – in order to conceive of human life, and human thriving, in a much broader, richer way.

In 2012, British economist Kate Raworth proposed a new economic theory in response to the global situation we find ourselves in in the 21st century. Dubbed ‘Doughnut Economics’, it presented a powerful visual model of sustainable development aimed at addressing the question:

In 2012, British economist Kate Raworth proposed a new economic theory in response to the global situation we find ourselves in in the 21st century. Dubbed ‘Doughnut Economics’, it presented a powerful visual model of sustainable development aimed at addressing the question:

How can we ensure that every human being has the resources they need to meet their human rights – but that collectively we do it within the means of this planet?

This idea was originally presented as an Oxfam Discussion Paper when Kate was working for the organisation. In 2017, she fleshed out her vision in a book entitled Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist.[1] This became an international best-seller and spawned wide-ranging discussion in circles as diverse as the Vatican, the UN General Assembly and Extinction Rebellion. We did an article on it ourselves in Beshara Magazine, seeing it as a hopeful move towards a different way of conceiving not only our economy and society, but also ourselves, allowing us to escape from identification with what Raworth calls homo economicus – the idea that we are defined by our roles as workers and consumers – in order to conceive of human life, and human thriving, in a much broader, richer way.

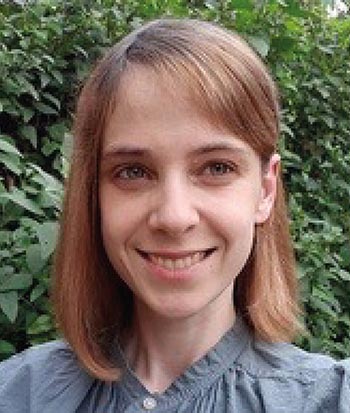

The basic conception of the Doughnut is simple. It consists of three rings. The outer one represents the ecological ceiling beyond which we cannot venture without damaging the earth upon which we all depend. The inner shows what Raworth calls the ‘social foundation’ which encapsulates the kind of human society that we wish to create. Between them, there is the safe region where we can live in harmony with our environment while also fulfilling our physical and social needs.

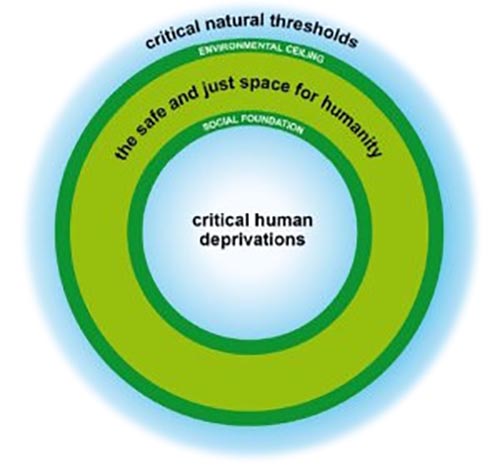

Relating this to our current global situation, Raworth broke down the rings into different elements. For the outer ring, she took the ‘planetary boundaries’ [/] identified in 2009 by a group of 26 earth system and environmental scientists led by Johan Rockström (Stockholm Resilience Centre [/]) and Will Steffen (Australian National University). They proposed that there are nine ‘planetary life support systems’ in terms of climate change, ozone depletion, water pollution, loss of species etc., which are essential for human survival. For the inner ring, she drew upon the United Nations’ sustainable development goals [/] to identify twelve essential aims (food, clean water, housing, sanitation etc.) which are generally agreed to be the foundations of thriving human life.

The power of the Doughnut is that it provides us with a visual, quantified representation – what Kate calls ‘a dashboard of indicators’ – of our situation at any given time. In 2018, when current data was fed into it, it showed that we were already exceeding four of the nine ecological boundaries and at the same time failing to meet the needs of the human population in every category. A complete updated version of the whole doughnut is due to be published in 2025. In the meantime, the diagram below shows an intermediate version with new planetary data for 2022, showing that we are now exceeding more than five boundaries. (For a more extended explanation of Doughnut Economics, see this TED talk by Kate, right or below, given in 2018.)

Video: A healthy economy should be designed to thrive, not grow; duration 15:53

The original 2017 doughnut with updated 2022 planetary data. The red areas are those where we are exceeding planetary boundaries. Image: Courtesy of Kate Raworth and DEAL

Move your computer mouse over the image to enlarge

The Action Lab

.

Often when someone comes up with a radical and acclaimed new idea, they follow it up with a stream of publications which explore different aspects of the same principles or incremental developments of the concept. This has not happened in the case of Doughnut Economics. Instead, in 2019, Kate and her strategic partner Carla Sanz Riaz co-founded the Doughnut Economics Action Lab (DEAL) as a place to connect everyone interested in putting the ideas into practice. It consists of a small team of enthusiastic people who work with changemakers to translate the theory into a living reality.

DEAL’s work is focused on six areas of potential change: Communities and the Arts; Cities and Regions; Research and Academia; Business and Enterprise; Schools and Education; Government & Policy. Leonora Grcheva is the Cities and Regions Lead, but we start our conversation by asking her a more general question about how DEAL first came about. “Well, Kate didn’t really write Doughnut Economics as a practical guide,” she explains. “Her aim was to bring together a whole range of different ideas, offering a new way of economic thinking. She didn’t conceive of the Doughnut as an instruction for local governments or communities or businesses to put the ideas into practice. But once the model of the Doughnut was out there, there was enormous interest from the community of changemakers around the world. People started picking up the ideas and experimenting with them on the ground. So this is how the idea of an action lab came about – as a response to emerging interest.”

She goes on: “I see the same thing in my own work with local governments – public sector organisations that are experimenting with these ideas. It’s all very emergent – very much learning by doing. It’s taking the framework of Doughnut Economics and many other inspiring ideas from a broad range of what we might call ‘post-growth movements’ and experimenting. Trying things out. Being brave and courageous enough to take some risks and work on new types of policy-making that aren’t based on the theories established in the 20th century.”

DEAL is basically a resource centre on which people can draw rather than an initiator of projects in itself. Its main work is developing tools – many of them visual aids – to help groups implement sustainable policies. It also runs workshops and seminars explaining the Doughnut vision and has developed a very comprehensive website where people can communicate and share their stories. Five years on from its inception, it is supporting a huge number of projects all over the world: these include 50 cities and regions looking to implement new policies, strategies and projects based on Doughnut Economics; 500 companies exploring the deep design of their business models; 60 community groups running local projects; and a growing number of national governments – among them Belgium, Bhutan, Ireland, Luxembourg and the UK – adopting some aspects of the Doughnut model in developing sustainable policies.

Many of these projects, Leonora tells us, are at the stage of looking at emerging practice rather than being able to present concrete results from working with the Doughnut. “It’s very early days. We aim to iteratively learn from what people are doing, creating tools and materials and resources that can support further innovation. Then we jointly take stock and try to think, okay, what is actually happening? How can we theorise about what’s coming up? It’s all very fluid, ever evolving.”

Officials in Amsterdam in a workshop to develop their city portrait. Image: from How the Dutch are reshaping their post-pandemic economy: BBC REEL [/]

Cities and Regions

.

Moving on to Leonora’s particular area of concern as the Cities and Regions lead, we comment that this seems to be an especially important area at the moment, when for the first time in history the majority of human beings are living in cities. A lot of movements developing sustainable economic models have a rather ‘back to the land’ kind of mentality, but if we’re going to solve our ecological problems, we’re surely going to have to solve them in cities.

Leonora begins by explaining that while she would not disagree, the title ‘Cities and Regions’ actually encompasses all sorts of human settlements; it’s basically a short-hand way of referring to any kind of place-based local authority. So her remit encompasses boroughs and municipalities as well as cities, villages and towns. At the moment, she is actively working with about 50, including bigger cities such as Amsterdam, Brussels, Glasgow, Copenhagen, Ipoh (Malaysia), Izmir (Turkey) and Barcelona, but also smaller cities like Grenoble, Nanaimo in Canada and Dunedin in New Zealand, and rural regions such as Cornwall in the UK and Tomelilla in Sweden.

So, what is it that motivates a city or a region to get in touch with DEAL? “I think that one of the main motivations is the recognition that there is a need to break out of siloed, sectoral ways of working and thinking. We live in an era of complex social and ecological challenges – climate change, biodiversity breakdown, massive inequality. These are multi-faceted problems that aren’t designed to be solved by a single department in a specific silo. But our local governments are still predominantly organised into separate departments that have very limited interactions with each other. So, people come looking for ways to work across silos, across teams, across ideas – in other words, more holistically.

“This desire, in turn, often translates into looking at new ways of defining a vision that is an umbrella, a unifying framework, that everybody can work towards. People working in several different organisations have told me that during the course of their day-to-day work, delivering tasks they have inherited, they have at some point reached a place of questioning the very purpose of their public body. They are asking: What is the work of local governance? What were we meant to be doing? Who or what are we here to serve?”

In other words, they have lost their sense of mission and vision. “Yes. So working with the DEAL means that they have a chance to take a step back and redefine their role and their political objectives.”

Participants in Doughnut Day 2024 in Valle de Valle de Bravo, Mexico. Photograph: Courtesy of DEAL

Rolling Out the Doughnut: The Four Lenses

.

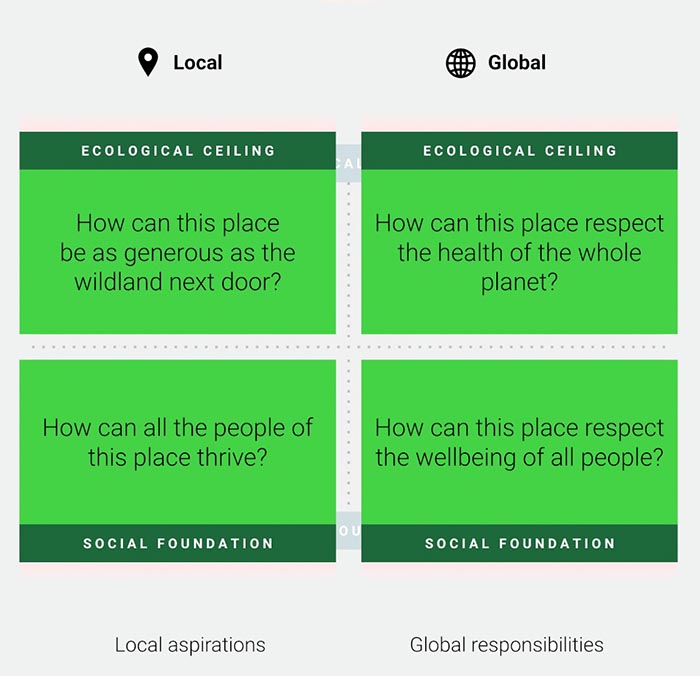

DEAL has developed a number of tools which help local governments refine their objectives in a structured way. As Leonora explains: “The Doughnut invites us into this vision of meeting the needs of all people within the means of the living planet. Translating this to the scale of cities and regions adds the additional dimension of thinking both about the local aspirations of the place – the needs of the people who live there and the ecology on which the city is built – but also to reflect on its global responsibilities. This can include its impact on the planet, on planetary health and the planetary boundaries as they are laid out in the global Doughnut. It also includes consideration of the people who live beyond the boundaries of the city or region and how they might be impacted by its activities. So we have developed this framework at a city scale which means looking at the situation through four lenses: local social, local ecological, global social and global ecological.”

The four lenses. Image: Courtesy of DEAL

At the moment, we largely assess whether a city is thriving almost entirely in terms of monetary values or standard economic indicators – the level of employment, what salaries are paid, house prices, etc. But, obviously, when thinking about the holistic vision embodied in the Doughnut, we have to take account of all sorts of other factors. Leonora agrees: “Yes, this is one of the guiding questions that we invite cities to consider through using the tool of the four lenses. We can always look at access to housing, to energy, to water, to community, to mobility, etc, etc. But depending on the place, we can also look at, say, access to spirituality and the many other things that mean thriving for a local community. When looking at our local ecology, we can include the health of our soil, the health of our waterways, the degree of biodiversity, the quality of the air and so on.

“So instead of narrowing down the entire human and ecological experience of a place to a single monetary indicator, we devise context-based indicators which are specific to that area. These include measures of what we’re currently doing, but we can also aim to set targets for what we are aiming to achieve.”

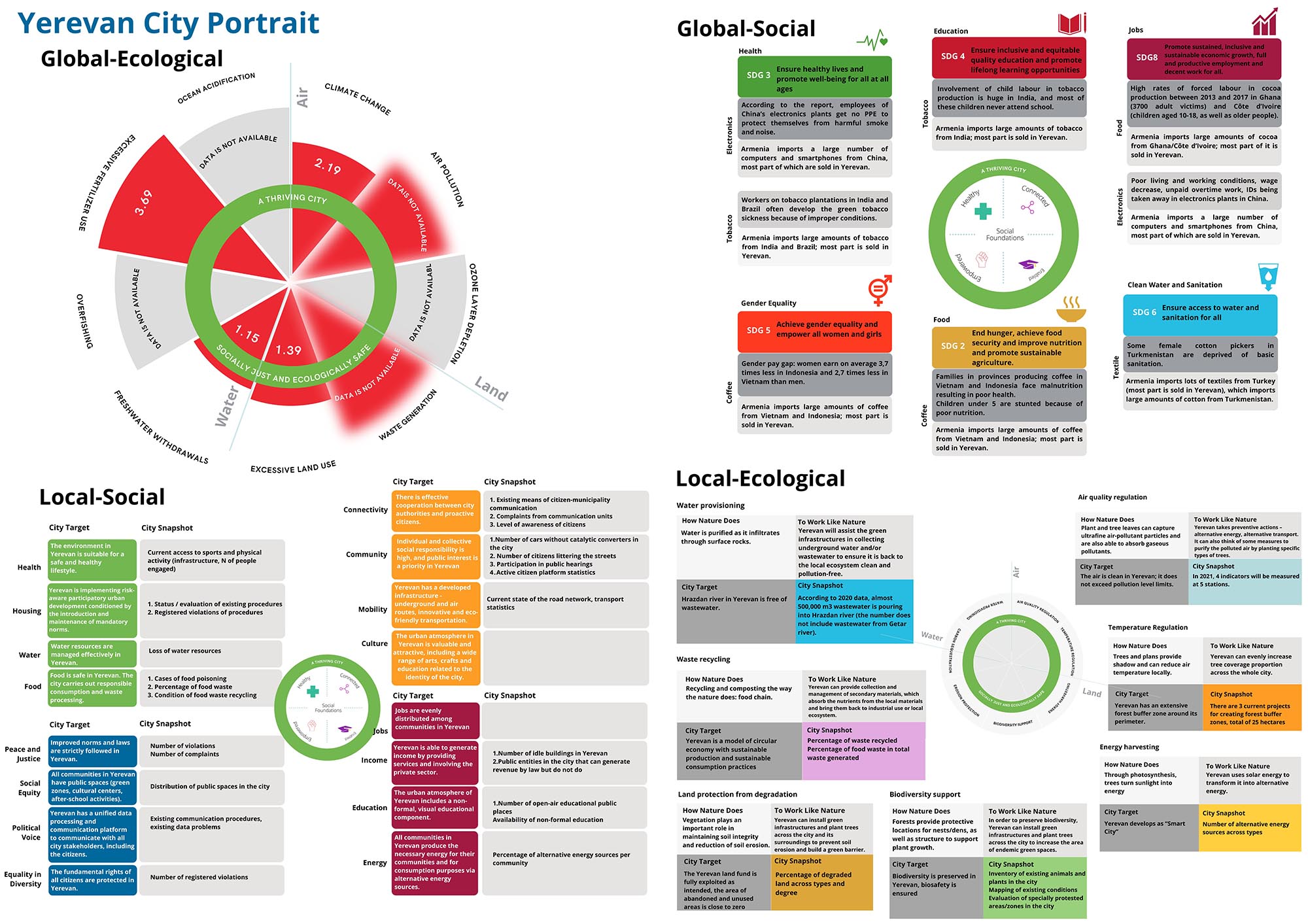

This means that each region or city generates a set of metrics and targets which are specific to their area, effectively producing a localised version of the Doughnut. We comment that while this is clearly an interesting and valuable aim, it must also be enormously problematic in terms of collecting the data needed to turn the Doughnut into a quantified model. “Indeed. Municipalities often have many types of data lying across many departments and organisations. They also have many types of targets that are related or unrelated to each other. So if you were to ask a place, say a city like Oxford: how are you doing right now? the council would probably struggle to give a concise, simple answer. Therefore, one of the first things we invite people to do is to develop a portrait of their region showing how they’re doing against a set of social and ecological indicators. This amounts, as you say, to a kind of localised version of the Doughnut.”

So this comes back to the need for the different sectors of government to be moving out of their silos and working together to get a whole picture. But how do people decide what they are going to measure and what targets they want to set? Is it through consultation with the local community? Leonora answers: “Well, ideally, all processes should be highly participatory, especially when it comes to setting targets. But when it comes to the specific methodology, we don’t prescribe a process, because how could we design a methodology that would be as equally valid in Oxford as it is in Mexico City or in Bangalore? We try to encourage and support places and maybe nudge them in a certain direction; we have conversations, group discussions, create new materials. But, in the end, it’s completely up to people in the places themselves how they do it and who they involve in the process.

“Many of the cities we are working with are at the stage of developing their portrait and it is an area in which we are seeing a lot of newly emerging practice. People are having to develop alternative ways of agreeing on budgets; of identifying the needs of their area; of working out where cross-sectoral collaborations need to happen; of deciding how to prioritise decisions at all scales, etc., etc. They also have to find ways of collecting the data to feed into their portrait; some of it is very science-based and can be gathered from existing surveys and sources; sometimes it does not yet exist, and new methods of calculation have to be devised. And some of it is based on conversations and participatory processes with the local community.”

City portrait developed by the city of Yerevan (Armenia). Image: Courtesy of DEAL

Move your computer mouse over the image to enlarge

The Global Dimensions of the Doughnut

.

Many regions will probably already have metrics and targets in place for local issues. What is really new in the Doughnut model is the idea of connecting these to the global situation. What does it mean, for instance, to look at the social impact of a city on other communities? Leonora agrees that this is a difficult question. “Because at the moment it isn’t typically a part of the conversation. However, there are areas where regions clearly have a quite explicit impact on outside communities, for example through procurement. Cities are procurers of a lot of materials; they completely rely on resources from elsewhere. In fact, with very few exceptions of some indigenous communities or mini self-sufficient villages, we all, nowadays, rely on resources brought in from other places, whether it’s food, retail goods, electronics or construction material.

“A city or a municipality has many roles in directly regulating or developing policies of procuring and supplying themselves. They also have a lot of power – power to act through local types of regulations and financial subsidies to develop ways of working differently. So it’s a matter of building a culture, a kind of education in awareness in terms of sustainability and the changes in our consumption and production patterns that are needed if we are to live within the safe zone of the Doughnut.”

A good example of this is the city of Barcelona, which was among the first to complete a detailed portrait of its activities using the Doughnut framework [/]. The project, which was initiated in 2021 through a series of workshops and conferences and completed by 2023, identified 200 indicators over the four lenses. Some of these were calculated by collating data from different bodies within the city, including universities. However some required further research, and this led to the pioneering of a new methodology to quantify the connection between the city’s material footprint and social indicators of countries producing goods consumed in the city. They came up with 11 different metrics for the ‘global social’ lens, resulting in the discovery that ‘a staggering’ 96.7% of the resources consumed in Barcelona came from countries in more precarious situations than Spain. Its report in 2023, available on the DEAL website [/], comments that: “[This is] a sobering reminder that our current international trade model perpetuates existing vulnerabilities and struggles of the Global South”.

A similarly sobering result came from the assessment of the city’s impact on planetary ecology. The Doughnut revealed that Barcelona is exceeding six of the seven planetary boundaries, and that it would have to cut its CO2 emissions by 400% to meet the Paris Agreement’s goal of stabilising global temperature rise at 1.5ºC. (For more on this project, see the video on the right or below.)

Video: Barcelona Data Portrait; duration 26:39

Another pioneering city to embrace the Doughnut model is Amsterdam, which produced its portrait in 2020. The project generated a set of 49 separate goals to be achieved by 2050, with the overarching aim of achieving ‘a circular economy’. This is an attempt to tackle the interface with external communities by taking in less raw materials and giving out less pollution so that the city is a more self-contained and self-reliant unit. Leonora, however, points out that this is a good example where using the approach of the four lenses can put a strategy into a different light. “This target in Amsterdam is all about reusing and circulating materials. But if it is taken out of the context of planetary boundaries, a circular economy can also become part of the never-ending growth machine. This is because however hard we try to re-circulate material, there is always going to be some waste. Therefore, this policy has to go hand in hand with an overall reduction of how much material we extract and how much waste we produce.”

“So, this is one of the ways in which the ideas of Doughnut Economics broadened and deepened the circular economy strategy in Amsterdam. We can talk about local self-sufficiency and more ethical and smartly-managed regional supply chains, etc. but at the same time we need to recognise the planetary impact, and also the social side of the circular economy, so that we are transitioning towards reducing our overall impact in a socially just way.” (To read more stories from towns, cities and regions that worked with Doughnut Economics, check out DEAL’s guide Cities & Regions: Let’s Get Started [/].)

Public participation in creating a city portrait in Kakao (South Korea). Image: Courtesy of DEAL

Changing Values

.

One of the big assumptions that Kate tackles in her book is the notion of homo economicus – what she calls the ‘caricature’ of human beings as consistently rational agents who are narrowly self-interested and who pursue their subjectively defined ends optimally. She maintains that if we’re going to have a new sort of economics, then we need to portray ourselves differently so that we represent humanity in much more complex and comprehensive ways. So to what extent, we wonder, do the city projects discuss this kind of deep change in our understanding? Do they also involve a kind of education in coming to see ourselves differently?

Leonora tells us that this idea plays a very large role in all that DEAL does, including the Cities and Regions projects. “When we ask cities; what have been some of the main benefits of working with the Doughnut?, many of them say that it’s given them a new language, a new narrative, and therefore a new way to conceptualise who we are, how we position ourselves as part of the living world, and how we can reimagine our future. For me, personally, this was a very important aspect when I first came across these ideas in Kate’s book. It gave me a way of putting all sorts of thoughts and observations and urges that I already had into a coherent narrative. So you can call it an education but for me it is best described as a new kind of conversation.

“And this conversation is ongoing. At the core of nearly all the problems we have today is the idea of separation between the human and the natural worlds. I think we have a long way to go to unlearn this so that we stop giving ourselves permission to infinitely extract from the living world that sustains us. Doughnut Economics is just one of many concepts, including scientific concepts, that are giving us a narrative which reconceptualises this understanding.”

Part of this new narrative, we suggest, has to be a reassessment of what we think happiness is. At the moment, it is very much conceived in terms of materialism or consumerism – we think that acquiring things will make us happy or at least alleviate our suffering. We need to educate ourselves about other forms of satisfaction. Leonora tells us this had indeed been a part of the strategy in several cities. “In Barcelona, for instance, one of the policies that they have developed is a sustainability culture strategy called ‘We Change for Climate’. The focus of this is not just on the type of actions and initiatives we need, but on the shifts in our culture and set of values that allow us to behave, or not behave, in a certain way. They have identified a number of shifts that need to take place, such as moving from consumerism to sufficiency, from competition to collaboration, etc. Our values underpin our actions; we don’t always speak of them, but they’re really the building blocks on which we build so many of our actual policies.”

Cities participating in DEAL, 2024. This is taken from an interactive map which shows all of DEAL’s activities. Click here [/] to access. Image: Courtesy of DEAL

Move your computer mouse over the image to enlarge

Regions and Cities as Catalysts for Wider Change

.

Finally, we ask Leonora about the extent to which regions and cities can effect widespread change, given that they have very limited powers compared to the national government. Are they not extremely constrained in what they can achieve? Leonora agrees that most local governments are, although the extent to which they can operate independently varies greatly from country to country; in the UK, things are very centralised but in other parts of Europe, for instance, in France, regional governments have significantly more control. “Generally, it is true that much of what happens in a city, in a village or in a region is bounded by the finances and the regulations set by a national government. But it is also the case that in the world of economics change often begins on a small scale, whether it is at the level of individual projects or innovating businesses. National governments tend to be a bit slower in how their wheels turn.

“So, we’re hearing that innovations being introduced by cities or organisations are triggering interest at a national level. They are causing governments – not just here in Europe but across the globe – to start paying attention because suddenly they can see that these ideas are not just theories; they are things that are alive in practice. And they’re curious to understand more. Some are more than curious; they’re ambitious to do something to actually support the emergence of a more sustainable way of doing things.”

We comment that the policies which Leonora has described make sense from many perspectives. The siloing of different departments within local government, for instance, is almost certainly leading to a lot of wasted resources and duplication of effort. “Yes, it’s true that some of the cities that have started working with these ideas internally – especially those that have increased their cooperation across sectors and started to harmonise their decision-making processes – have reported that one of the most immediate effects is an increase in operational efficiency. They are simply more efficient now that they are all working together.”

On this hopeful note, we have to bring our conversation to an end. We thank Leonora for a fascinating insight into the work of DEAL, which we feel is one of the most exciting projects happening at the moment in terms of showing how unified perspective can have a real practical effect in the world. We wish them every success and hope to keep in touch with their progress.

For a more detailed presentation on the Doughnut Unrolled, see this video by Kate:

Video: The Doughnut Unrolled and the Four Lenses; duration 11:35

Cartoon by Simon Blackwood

Image Sources (click to open)

Banner: xyz

Inset: Leonora Grcheva.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] Kate Raworth, Doughnut Economics (Random House, 2017).

The text of this article has a Creative Commons Licence BY-NC-ND 4.0 [/]. We are not able to give permission for reproduction of the illustrations; details of their sources are given in the captions.

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

Video: A healthy economy should be designed to thrive, not grow; duration 15:53

Video: Barcelona Data Portrait; duration 26:39

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Doughnut Economics

Kate Raworth’s new book asks how we can reconcile the needs of humanity with the needs of the planet

The Revival of the Commons

Political strategist David Bollier explains how a new economic/cultural paradigm is challenging the increasing ‘enclosure’ of wealth and human creativity

The Future Prospects for Humanity

Martin Rees, the Astronomer Royal, on the threats to our survival in the 21st century, and the need to take a cosmic perspective

The Ecology of Money

Ciaran Mundy, Director of the Bristol Pound, explains the difference between money and real wealth

READERS’ COMMENTS

Brilliant piece