Well Being & Ecology _|_ Issue 18, 2021

Paddling the Magic Canoe: The Wisdom of Wa’xaid

Briony Penn talks about her relationship with the native elder Cecil Paul – Wa’xaid – and their successful campaign to preserve the glorious Kitlope River area in British Columbia

Paddling the Magic Canoe: The Wisdom of Wa’xaid

Briony Penn talks about her relationship with the native elder Cecil Paul – Wa’xaid – and their successful campaign to preserve the glorious Kitlope River area in British Columbia

Cecil Paul (Wa’xaid), who died in December 2020, was an elder of the Xenaksiala/Haisla nation from the Kitlope River watershed on the West coast of Canada. Taken from his family and culture for ‘re-education’ at the age of ten, he eventually returned to his native lands and became an active campaigner to protect them from logging and commercial exploitation. David Hyams and Jane Clark talk to his friend, the writer and artist Briony Penn, who has recorded Wa’xaid’s stories and biography in two recent books, about what this wise, gentle man can teach us about life and our relationship to nature.

Briony Penn is a Canadian naturalist, writer, artist and broadcaster who has become known for her efforts to protect species and environments in her native British Columbia. Her two most recent books have centred on the life and wisdom of Cecil (seesil) Paul (1931–2020) – native name Wa’xaid (Xaid here is pronounced ‘chaid’, with ch as in loch) – a member of the Xenaksiala/Haisla nation from the Kitlope River watershed on the West coast of British Columbia, with whom she became close friends.

Briony Penn is a Canadian naturalist, writer, artist and broadcaster who has become known for her efforts to protect species and environments in her native British Columbia. Her two most recent books have centred on the life and wisdom of Cecil (seesil) Paul (1931–2020) – native name Wa’xaid (Xaid here is pronounced ‘chaid’, with ch as in loch) – a member of the Xenaksiala/Haisla nation from the Kitlope River watershed on the West coast of British Columbia, with whom she became close friends.

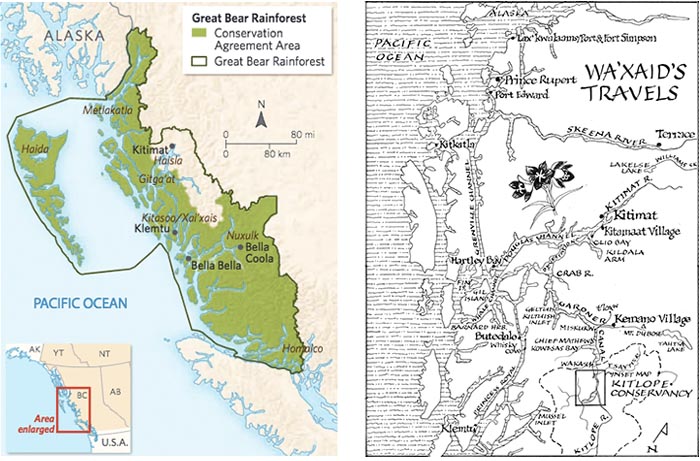

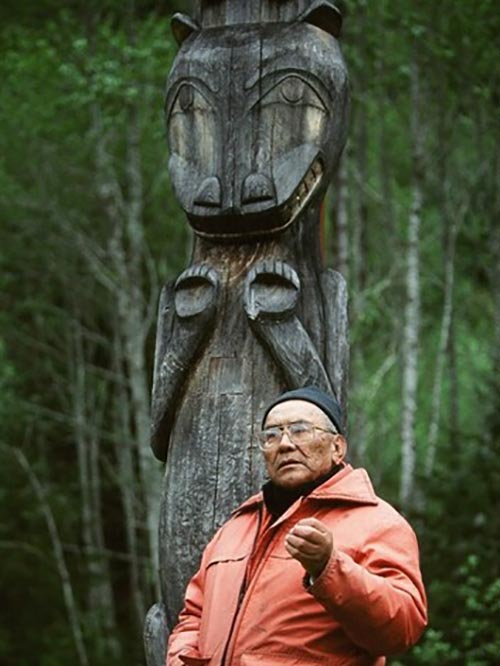

Stories from the Magic Canoe of Wa’xaid [1] is a rendering of Cecil’s stories in his own words, whilst Following the Good River [2] is a more detailed biography which includes a comprehensive account of the campaign which he initiated, with the help of many others, to preserve his tribal lands from destructive resource development. In 1996, this won a historic victory when the Kitlope became a protected conservancy, co-managed by the Federal government and the Haisla nation. Covering almost a million acres, it is now the largest area of protected temperate rain forest on the planet.

The Magic Canoe begins with a quote from Cecil in his native tongue with the instruction: “Lä göläs – Put your canoe ashore and rest,” [3] that is, “Let go of everything and listen carefully!” This exemplifies the traditional teaching methods of his people. The wise elders will not speak unless they know that they have an audience that is fully present and listening. If not, they just leave the teaching for another time.

‘The Arrows that Came My Way’

.

In the book, Cecil introduces himself like this (to hear this in his own words, see video right or below):

Video: Good River – Wa’xaid. Duration: 3:57

The Place of My Birth. They call it the Kitlope …. My name is Wa’xaid. Wa is ‘the river’, Xaid is ‘good’ – good river. Sometimes the river is not good. [4]

With this he anchors the story of his life in his bond with his land and his ancestral river valley. He also intimates that his life has not been easy, and Briony’s biography makes it clear just how hard it was. He was born in 1931, at a time when it was government policy to stamp out native languages and cultures by ‘re-educating’ Indigenous children. Until the age of six his life was idyllic in the care of his family, playing and learning traditional culture on the shores of Kitlope Lake. His life revolved around his grandmother, Annie Paul – his ‘little granny’ – who took on the role of his teacher. She was the matriarch of his family and a leader of their tribe – a leadership which covered both the secular and the spiritual.

Canadian law at the time required, on pain of imprisonment, that Indigenous children like Cecil attend a nearby boarding school run by women missionaries. His grandfather tried to hide him, but at the age of ten he was caught by the authorities and spent four years shut up in a boarding school for Indian boys run by the United Church of Canada, at Port Alberni, more than 1000 kilometres from home. The regime there was harsh. The boys were beaten and abused; they were denied the use of their mother tongues and had to speak only English. This made it impossible for some of them to communicate later with their families, but Cecil hung onto his language (in fact, at the time of his death he was one of only four people who spoke it) and survived by developing a deep hatred for the missionaries who ran the school.

But the sense of shame and humiliation he had experienced stayed with him long after he left. He dealt with it through drink and lived the life of an alcoholic for the next forty years, working in a series of manual jobs along the British Columbia coast. He became skilled at loading logs floated down the river into trucks for transportation to the paper mill, and also worked in a fish cannery, on fishing boats, and with teams surveying the land for logging roads.

Briony first met him in the 1980s, when he had stopped drinking and had returned to the Kitlope as part of his healing journey. She had just completed her PhD from Edinburgh University in Scotland and was working on the boat The Maple Leaf which was engaged in eco-tourism – an important source of income for the region. “Cecil would join us on the boat and told his stories. That is when I started to record him. I captured him on my old-fashioned mini-cassette, and later wrote up what he said. In the beginning he just told beautiful stories about the environment, and it was only much later, when a degree of trust had built up, that he started to talk about what had happened to him at the residential home. He called all that ‘the arrows that came my way’.

Left: Map of the Great Bear Rainforest within which Kitlope is situated. Right: Map of Cecil’s travels, showing the location of the Kitlope Heritage Conservancy, from Following the Good River

Some History of the Xenaksiala/Haisla Nation

.

Cecil’s own story sits within the wider narrative of the Indigenous communities of British Columbia. The area was ‘discovered’ almost simultaneously in 1793 by Captain George Vancouver by sea, and by Alexander Mackenzie who reached the West coast overland from the interior via the Haisla ‘grease trails’ – trading tracks which had been used for thousands of years to transport the oolichan fish oil which is essential to the Indigenous diet. At the time of discovery, the native communities were thriving, continuing a way of life based on fishing and hunting which they had followed for millennia.

But contact with Europeans brought disaster. In 1862, smallpox spread from the Hudson Bay Company’s Fort Simpson trading post to neighbouring Indigenous lands, devastating the population. Briony quotes a calculation [5] that it decreased by between 75 per cent and 100 per cent. Smallpox was followed by the influenza epidemic of 1917–19, and then the arrival of tuberculosis from around 1937, with the medication streptomycin being withheld from Indigenous patients until around 1946. Cecil’s grandmother told him that before the arrival of Europeans the population of the Xenaksiala was around 700, but in the 1934 census, it is listed as merely 30 people. To survive, the women intermarried with the neighbouring Haisla clan, which is why Cecil had a connection to both peoples.

The population reduction had radical implications for the management of the land. The Xenaksiala/Haisla tradition of land stewardship defined a family’s area of ownership as being over a whole watershed – from the highest peaks and ridges down into and along the river valley below. This was called a wa’wais and it allowed them to manage the entire ecosystem, harvesting plants, fish and animals from rivers and woods at different times, year round, to preserve the overall balance. However, government agents, noting the reduced size of the Indigenous population and being ignorant of their farming methods, created very small reserves for them to live in and supposedly cultivate. Kitamaat, the reserve where Cecil lived, consisted of just 35 acres of stony ground in which crops would not grow.

Ownership of the remaining land was assumed by the Canadian Government without further discussion. Although, legally, the 1763 Royal Proclamation guaranteed the rights of the Xenaksiala to hunt and fish on their traditional tribal lands, and recognised their system of law – known as the Nuyem – permits were nevertheless granted to large corporations for logging, for oil and liquid natural gas pipelines, for hydroelectric schemes and for fish farms. For these, the Indigenous population was seen as simply a source of cheap labour – and sometimes a minor irritant.

Ka’ous/Kitlope Lake, which Cecil called his ‘cathedral’. Photograph: Courtesy Sam Beebe

The Magic Canoe.

.

The story of the campaign which saved the traditional Haisla lands from development forms the backbone of Briony’s account. She describes how, on a family visit to Kitlope in 1990, Cecil found survey markers attached to trees at his family’s summer camp. He at once understood that the valley was being prepared for clear-fell logging and resolved to protect it from the damage he had seen in neighbouring valleys, where clearance had destroyed not only the physical environment but also the creatures who lived in it – deer, moose, bear, beaver, oolichan and several species of Pacific salmon – upon which the Haisla people depended.

He went into a period of fasting and retreat to ask the Great Spirit for guidance. Then one day, sitting by his granny’s tree on the lakeside at Kitlope, he heard her spirit asking him what he wanted and told her of the threat to the valley. She told him that she had a vision: he would launch a magic canoe which would attract lots of people to come aboard to help. There would be many paddlers, but the canoe would expand to create space for everyone. It would never be full.

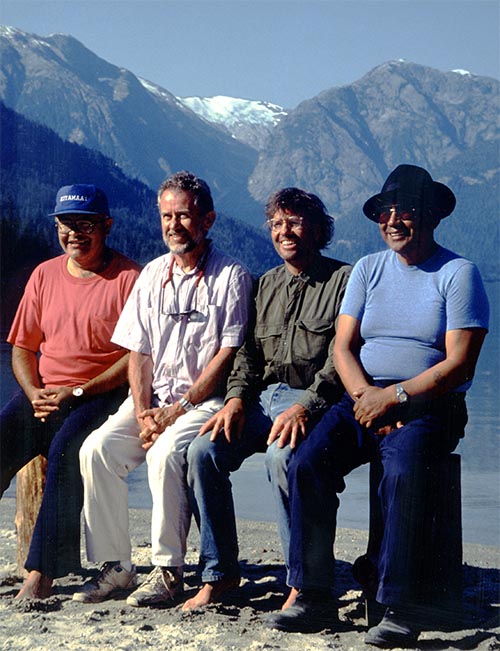

This vision motivated Cecil to begin his campaign, and very soon the ‘canoe’ began to fill up with local friends, with academics and eventually with activists from across Canada and the United States. Spencer Beebe and Ken Margolis, environmentalists from Portland, Oregon, who specialised in recording the condition of rainforests around the world, brought a scientific perspective. Colleagues of theirs, using satellite imagery, calculated that the Kitlope was the largest intact rainforest watershed in the world. Celebrities offered support. Students came to lend a hand, along with environmental organisations and Indigenous peoples’ networks from across the continent. Cecil found himself addressing public meetings, coming into contact with government officials and travelling to conferences with Indigenous tribes as far away as Australia and South America (see video right or below for his comments upon oil and gas pipelines).

Video: Good River – Good River – Oil vs. Natural Gas. Duration: 2:20

To begin with, the group’s objections to the logging were ignored, but as time went on, more and more evidence was presented, resulting in more and more publicity, and eventually widespread public understanding of the effects of destroying this beautiful and pristine environment. After years of negotiation, in 1996 the company concerned – West Fraser Timber – withdrew from their contract without compensation. In 2006, after further negotiation, the government agreed to protected status for a Kitlope Heritage Conservancy, to be jointly managed with the Haisla Nation. Cecil’s son, Cecil Junior, was one of the first Conservancy Watchmen tasked with protecting the environment and guiding visitors.

The whole process was a triumph for cooperative action, and for the gentle negotiating strategy that Cecil advocated:

I keep telling my people, ‘Negotiate in good faith, with easy language, no cursing. Got to tell them who you are. Sometimes if you go in with anger, you make an avalanche with all that noise.’ [6]

It is also a triumph for what Briony calls ‘a two-eyed approach’, which she explains as “the bringing together of two different worldviews: one is the scientific worldview, and the other is the relational worldview, which is the view of Indigenous peoples. People are realising that when you combine the two, you get a pretty amazing point of view.

“Campaigns against things like oil extraction and hydroelectric plants are still going on, of course – these companies are going to go down kicking and screaming. It’s a step-by-step process. But what we are seeing now is also a coming together of environmental activists and Indigenous rights campaigners. And this was really Cecil’s message: we’ve all got to get into the magic canoe. We get in because we are all connected; we are all relatives; we cannot be siloing our activities at this point in time”.

Some of the friends and conservationists who got into the ‘magic canoe’. Left to right: Gerald Amos, John Cashmore, Spencer Beebe, Cecil Paul, Kitlope 1993. Photograph: Courtesy Spencer B. Beebe

The Importance of Relationship

.

A striking aspect of the ‘magic canoe’ is that it includes people from all cultural backgrounds. At one point, Cecil comments on the fact that in order to save his land he had to work with people – white people – who for many years he had hated deeply. Briony agrees: “One of the most remarkable things about Cecil was his ability to forgive people for incarcerating him in that dreadful children’s home, or for polluting the rivers and destroying the beauty of his homeland – for almost losing his language, his family, his culture. And this ability to forgive was predicated on the understanding that the people who committed these acts were in a cultural system which is badly flawed, so he did not hold them personally accountable. And I found that remarkable. It was great for me too, because rather than hating me because of my background, I was welcomed into his world from the very beginning.”

Meeting him was obviously very important to her personally, as well as professionally as a naturalist. “Yes, it was a personal epiphany. I come from a fairly middle class, privileged white family and my ancestors were colonists in British Columbia; they were the people who behaved so badly towards the land and the people here. Although I already knew the history and had in some ways rebelled against my colonising roots, I soon realised that it was all fairly superficial. Cecil presented an alternative world view which was really coherent, but also really different.”

In what way different? “Well, I was brought up in the Judeo–Christian tradition, and that has a very different set of priorities in which nature, if it comes anywhere, is way down the list. God is not embodied in a forest or in a river. He is embodied in cathedrals and such like. So Cecil used to say that the lake was his cathedral because it was a way of communicating to Christianised people that nature was his spiritual home. If he had just said that the lake was sacred, this would not have meant anything because we don’t hold anything in nature sacred. As a child I may have felt that we did and there were certainly elements of it here and there – ‘all creatures great and small’ for instance – but as I grew up this did not tally with what I saw out of my window in the city.

“The thing I discovered with Cecil was a coherent world view and a culture which is all about relationship. If you get out of relationship then you are in trouble – and we are way out of relationship with the natural world. Our only way back is to try and change so that we are all thinking in a similar way, and try and paddle together.”

So, would she say that interconnectedness – relationship – was Cecil’s central message? “Yes, and not only from Cecil. All along the coast of British Colombia, there are different communities which all have their own language and their own way of understanding things, but this idea of interconnectedness is central to all of them. You hear it from elder after elder after elder.

“Cecil’s ability to forgive was coupled with this deep understanding that we are all interconnected. We can only forgive someone if we really believe that they are our brother, our sister, our relative; because we have to forgive our brother and our sister even when they do things that we don’t agree with what they do.”

Bald eagle, Haliaeetus leucocephalus, catching oolichan fish in the Skeena River, BC. Photograph: Evan Spellman [/] / All Canada Pictures / Alamy Stock Photo

The Importance of Nuance

.

Another principle that Briony feels is central to Cecil’s message is that of nuance: the understanding that we have to look at things in detail and understand the specific conditions under which the natural world flourishes. For her, this is an intrinsic part of a world view based upon relationships. “Relationships are very nuanced. All the relationships we have, both with one another and with the outside world – with the natural world – are characterised by diversity and complexity, and it is not really possible to think in absolute terms. This is extremely important when considering things like climate change and species extinction.

“A specific example of this is the way our fisheries policies here in Canada have dealt with the herring. They dealt with it as just one big population, failing to see that there were levels of complexity within the shoals. Herring have a culture within which there are lineages, and generational teaching where the older fish guide the younger fish into very specific bays and estuaries. So when they started to fish the population and took out all the bigger fish, the little ones didn’t know where to go. The result is that we have wiped out our herring, just like Scotland wiped out theirs.

“Cecil paid a lot of attention to these small forage fish which are at the bottom of the food chain. His people always put them at the bottom of the totem pole because they hold everything up – all the other species depend on them. The main forage fish in this region is the oolichan (also, eulachon), which is a long, thin fish about the size of a biro. It is often called ‘the candlefish’ because it is so oily that you can actually light it like a candle. This is now a protected species under Federal law, and this was one of the factors in stopping the logging because of the nuance – the detail – of where the fish spawn and the timing of the spawning; felled trees wreck the river bottom and so destroy their spawning places.”

Cecil in front of the grizzly bear at the bottom of the G’psgolox totem pole replica. One of his big achievements was to negotiate the return of this pole from the Museum of Ethnography in Stockholm, where it had been taken without permission from the Xenaksiala people. Photograph: Courtesy Kevin Smith, M’iskusa 2006

The Importance of Stories

.

Briony goes on to explain that the Indigenous leadership has always focused on the law as their main tool for preserving not only their rights as human beings, but the rights of the natural world to be maintained in a sustainable way. Current campaigns are working towards introducing a carbon tax for instance, which would discourage the logging companies, as logging produces a lot of carbon. There are also moves to adopt the United Nations Declaration of Rights of Indigenous Peoples in some provinces. These kinds of law are formulated according to Western custom – written down and passed by parliament. But what about the Indigenous system of law, the Nuyem, which is now being incorporated into the management principles of the Kitlope. Surely, we ask, these are not formally written down?

“No, they are encapsulated in stories – in teaching stories. Cecil explained to me that there are all sorts of different types of stories, and they are passed down from generation to generation in the winter houses. Some of them embody the Nuyem, and these are a bit like the ten commandments, or Biblical teachings which are embedded in the text, like the story of the Good Samaritan helping a stranger. They embody very strong protocols, and there are strict rules about who can share those stories because they are often owned by a clan. They are also usually tied to a place, so that the place triggers the story. For example, if you are paddling by a specific big feature, like a waterfall, it would be embedded in the story.

“And then there are personal stories. The stories I gathered in The Magic Canoe were Cecil’s personal stories, which are shared in order to help the listener understand something. And those are a very different class, although some of the ones he told me are based upon Nuyem stories. One of these is a frog story. He did not tell me the Nuyem itself, but he told me that, as a child, he had been told a story about frogs and he ignored the message in it. So, his personal story was a teaching story about not listening.”

The Boreal-chorus frog, a kind of tree frog native to Canada. It lives mostly in woodland ponds. Photograph: naturewatch.ca [/]

… and Frogs

.

There are quite a lot of stories about frogs in the Nuyem, we gather. Is this because frogs have a particular significance for these cultures? “These stories are all about the sacredness of frogs. They tell people that if they kill a frog, they will die. If we take a two-eyed approach – meaning that we try to see things in terms of Western thought as well as Indigenous – we can understand that the frogs are the symbol of a healthy water supply. I have frogs here on my land, and if they don’t turn up in the spring, I’m super worried because it could mean that my well is contaminated. So a frog story is a way of expressing the importance of water and of clean water supplies.”

Putting it like this makes it clear that the idea of the sanctity of amphibians, which is so unfamiliar to us as Westerners, is actually very practical. “Yes, because as soon as you’ve lost your amphibians, you’ve lost your water catchment sites. These are the places where the water drains down and provide the long term moisture that is needed in summer. In winter here, you get rain and snow, but in the summer, when water supplies are at a premium, you rely on all those wetlands.”

One of the stories in Magic Canoe concerns an elder taking a group of young people on a mountain path. He tells them to walk very quietly and not make any noise, and then he makes a big bang. There’s a pool nearby and suddenly they can all see that it is full of frogs, as they leap out. Briony explains that the message here is that the movement of the frogs increases the flow of the stream.

“Many people find this frog story weird and they don’t get it. But you get it if you’re paddling up the coast in the summer, as there is hardly any water. There is plenty of salt water, but no fresh water, so it’s critical that there are these little wetland seeps – and this is probably what people do: they bang the rock, frogs jump in, and this increases the flow enough to give them the water they need. When you start to understand things like this, you begin to understand that these stories indicate a culture where people really know their environment and how it works.”

Grizzly bear in the Great Bear National Park, BC. Photograph: Ron Canning/iStock

The Wider Ecology

.

She goes on: “Cecil always said that water is going to be a big issue in the near future. Water is sacred and we are going to run out of it. Look at all the areas where there is desertification – African countries, and even California; I mean, the Colorado River doesn’t even run anymore. There are abused wetlands everywhere.

“People do of course understand the importance of water in general, and even within our Western traditions it is still seen as sacred in some way. But we have lost our relationship to the creatures that inhabit water – like frogs. When did these creatures that are so central to our survival start to be associated with bad things, like witchcraft? We still have pretty healthy amphibian populations on the island where I live, and there are people who, if they see a frog or a newt, will just go and squish it without thinking anything of it. Cecil would have seen such an action as a threat to the community, and people would have been told stories which conveyed to them that it was a punishable act.”

This talk of water reminds us of a passage in The Magic Canoe which describes how Cecil, when he took visitors up the river to Kitlope Lake, invited them to wash their eyes in the clear water of the lake so that they could truly experience what was before them.

“We are blind to Mother Earth. When you bathe your eyes in the artery of Mother Earth, that is so pure, it will improve your vision to see things. I will also ask you to wash your ears, so you could hear what goes on around you. So I could hear you talk. I could hear the wind, and you could hear the birds and animals. If you have the patience to listen, to hear the songs of the birds early in the mornings, all these things will be open to you.” [7]

Briony feels that it is important to note that, extraordinary as Cecil was, he was not the sole representative of First Nation culture in Canada. Along the coast of British Columbia, there are many communities and elders who are continuing their traditional ways of life, and who, because of the protection of the rainforest, can now look forward to a more secure future. “We are so lucky here on the coast to have so many working Indigenous cultures that are still alive. In other parts of the world, these cultures disappeared hundreds, if not thousands, of years ago. But they have survived here because British Columbia was colonised so late. If you live in Europe, for example, who were the first people and how could you learn from them? There is a huge opportunity on the West coast to see these principles in action, and we even have the possibility of incorporating the values into our own legal systems.”

Another blessing is that the big prey predator systems in the region are also still intact. The benefits of these for keeping ecosystems in balance are increasingly recognised, with places like Yellowstone Park in the US reintroducing them. (See our article on ‘Rewilding’) “When I was in Scotland, I was devastated to see what had happened to a similar temperate rain forest; the Gaelic names rememorate its past existence – names like ‘The Valley of the Bear’ – but it has all gone. The forests were felled, the animals – the beavers, the wolves – were killed, and now all that remains are the vestiges of these place names. It provides a real lesson for us in Canada.”

Briony and Cecil. Photograph: Courtesy Raincoast Conservation Foundation

Legacy

.

Finally, we ask Briony about Cecil’s death, which happened in December 2020, after Following the Good River had been published. (Click here for some tributes to him) What will happen now that he is no longer around? “Of course, this is the big thing in terms of all of our hearts. But he was 90 years old and had come to a point where he felt he was not enjoying life because of a change in his health. He was ready to, in his own words, ‘cross over to the other side’, or ‘go back to his home’. He used those kinds of metaphors. It was a very peaceful end. He felt that he had done everything he had set out to do – despite having gone through forty years of alcoholism, which was a huge amount of time to lose. Because of Covid, there has not been any ceremony yet. But eventually, he will be taken back to where the family totem pole lies and where his family lie.

“We miss him, but at the same time, he is still here. One of his teachings was that the power of mentoring and forming relationships means that our stories – the stories of our own lives and those passed on from our ancestors – live on as our legacy. This is very different from our Western point of view, in which we think of our lives in terms of individual achievements, of how rich we get, for instance.”

So, to end, it seems good to give the last word to Cecil himself, who explained the purpose of saving the Kitlope like this:

“In our language we call it Huchsduwachsdu Nuyem Jees. That means the land of milky blue waters and the sacred stories contained in this place. You think it’s a victory because we saved the land. But what we really saved is our heritage, our stories, which are embedded in this place and which couldn’t survive without it, and which contain all our wisdom for living.” [7]

Haisal Youth in a canoe on the Kitlope, 2004. Photograph: Courtesy Sam Beebe

To find out more about Wa’xaid, see Briony’s books:

Stories from the Magic Canoe of Wa’xaid (Rocky Mountain Books, 2019)

Following the Good River (Rocky Mountain Books, 2020)

For more on Briony, including some of her very fine artwork, see her website www.brionypenn.com. To listen to Briony talking about her book A Year on the Wild Side (2020), a compilation of her weekly columns, click here [/].

Image Sources (click to close)

Banner: Cecil Paul aboard The Maple Leaf. Photograph: Greg Shea.

First Inset: Briony at her home in British Columbia. Photograph: Courtesy Briony Penn.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] CECIL PAUL, ROY VICKERS & BRIONY PENN, Stories from the Magic Canoe of Wa’xaid (Rocky Mountain Books, 2019).

[2] BRIONY PENN with CECIL PAUL, Following the Good River: The Life and Times of Wa’xaid (Rocky Mountain Books, 2020).

[3] Magic Canoe, p. 13.

[4] Magic Canoe, p. 13.

[5] TOM SWANKY, The True Story of Canada’s ‘War’ of Extermination on the Pacific (lulu.com, 2013).

[6] Magic Canoe, p. 111.

[7] Magic Canoe, p. 16.

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

Video: Good River – Wa’xaid. Duration: 3:57

Video: Good River – Good River – Oil vs. Natural Gas. Duration: 2:20

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

READERS’ COMMENTS

0 Comments