Science & Technology _|_ Issue 3, 2016

Three Transitions

Richard Twinch contemplates the nature of cultural change

Three Transitions

Richard Twinch contemplates the nature of cultural change

Constant change is a defining attribute of life and living, not only for individuals but also for societies and cultures. It is the ability to manage transitions that determines, at a Darwinian level, whether we die or survive. However, transitions also offer opportunities which can result in transformation and rebirth – renaissance – into new spheres of being. September, itself a month of transition, brought me two lessons from history – one visual and the other visceral – as well as an encounter with the dystopian possibilities that our current processes of technological revolution are offering.

Constant change is a defining attribute of life and living, not only for individuals but also for societies and cultures. It is the ability to manage transitions that determines, at a Darwinian level, whether we die or survive. However, transitions also offer opportunities which can result in transformation and rebirth – renaissance – into new spheres of being. September, itself a month of transition, brought me two lessons from history – one visual and the other visceral – as well as an encounter with the dystopian possibilities that our current processes of technological revolution are offering.

The Transition into Tomorrow

.

The encounter with “A Brief History of Tomorrow” took place at the Royal Society of Arts (RSA) on 8 September. Here, the Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari presented his latest acclaimed work, Homo Deus, in which he looks to technological change – in particular the growth of computer science and bio-technology – as the instigator of tectonic shifts in our society. This knowledge endows people with powers that Harari says are “godlike” – hence the name of the book.

In the 21st century, the train of progress is again pulling out of the station – and this will probably be that last train ever to leave the station called Homo Sapiens. Those who miss the train will never get a second chance. In order to get a seat on it, you need to understand 21st-century technology, and in particular the powers of biotechnology and computer algorithms.

Harari foresees a future where, instead of the 19th-century “working classes”, we are in danger of creating a 21st-century “useless class” who will no longer have any purpose either militarily or economically. The picture he paints is one where those “on the train of progress” are pulling far, far away from those who are unwilling or unable to absorb the changes necessary.

This seems stark and brutal, but fortunately Harari is more nuanced; as he explained in his presentation, his purpose is “mapping possibilities rather than making predictions”. This in itself can have an effect; in Homo Deus he describes how knowledge can change the future, citing how the Marxist revolution only had limited application – not because the theory was wrong, but because capitalists could read what Marx said and make adjustments accordingly!

In the discussion, Harari called for a relevant education in “emotional resilience and intelligence” that is learned throughout our lives rather than becoming specialists in jobs which may be better done by machines. He also agreed with my observation about responsibility (about 39 minutes into the video), saying that we need to be “responsible to ourselves and to the world as a whole… So far, humankind has created havoc on the planet…the renewal of responsibility is a very important issue in the 21st century.”

However, in his chapter “The Time Bomb in the Laboratory”, which explains developments in neural mapping, Harari puts forward the opinion that the “liberal view” of freewill is an illusion, as we are dominated by cultural and other processes that predetermine our choices. This creates a logical impasse from which there is seemingly no way out: if beliefs are relegated to the random firing of neural networks, religions are merely a “spin” by those in power, and consciousness is seen as unnecessary in the new economic world order, Harari’s logic would seem to mean that we cannot make decisions freely. So how can we be responsible?

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

In Homo Deus, Harari describes “data-ism” – a term first coined by Steve Lohr of The New York Times – as the “religion” that is set to overtake “humanism” as the human experience become less central, and data flows increasingly exist to enhance “big” data rather than support human progress. One of the main credos is the belief that organic life is based on algorithms that are equivalent to the electronic ones created by computer scientists and the neural networks that they create. Harari himself admits: “We have no idea how or why data flows could produce consciousness and subjective experience.” But even if the theory proves to be wrong, he thinks that “it won’t necessarily prevent data-ism from taking over the world”.

Much like the striking predictions set out in the End of History and the Last Man by historian Francis Fukuyama at the end of the 20th century – which were literally blown away by the rise in fundamentalism (religious and otherwise) at the turn of the new millenium – Harari’s own predictions may well prove to be overstated. One way of putting them into context is to look at the way that transitions have come about in past periods when great cultural changes, or renaissances, have taken place, and how the human spirit has not only adapted and survived them but flourished.

The Anglo-Saxon Transition

One great renaissance I was privileged to experience at the end of September was that of Anglo Saxon spirituality and art that took place in the 7th and 8th centuries CE in Britain – or more precisely, in Northumberland, which was at that time the most powerful region of the British Isles. My companions and I had been invited on a short guided tour to follow ‘in the footsteps’ of St. Cuthbert (ca.634–87), the “best-known saint of the North” who to this day is venerated at his tomb in Durham Cathedral. And follow we did, ankle-deep in mud and sand as, on the first day of our pilgrimage, we crossed to the island of Lindisfarne as the sun set and the tide rose alarmingly. The plaintive cries of gulls and the melancholic wailing of the seals on a nearby sandbank could be heard rising above a strong wind. Nothing had changed much in the 1300 years or so since Cuthbert had made a similar journey, followed by numerous pilgrims over the ages.

It was on Lindisfarne that a new Christianity was nurtured, having made its way earlier with St. Aidan from Iona, which in turn had been brought from Ireland by St. Columba. Transitions, it seems, are many-layered and multi-faceted. St. Cuthbert’s arrival on Lindisfarne followed the Synod of Whitby in 667CE, which had decided that the Celtic Church should be replaced by the recently renascent Roman Church. Cuthbert was able to bridge the spiritual divide where most others could not, and to build a new Christianity that could accept both the hierarchical dictates of Rome and the requirements of his inner calling. What followed was an extraordinary flourishing of the arts and learning, infusing elements of Celtic, Mediterranean and Anglo-Saxon culture, which lasted until the Norman invasion 400 years later.

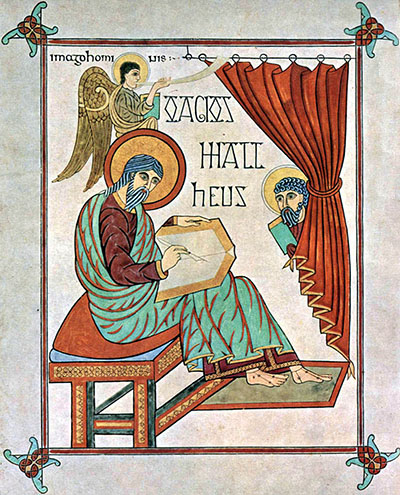

We were accompanied by a magnificent series of radio programmes by Melvyn Bragg “The Matter of the North” [/] that covered our journey in its first two episodes. Bragg identifies the Lindisfarne Gospels, written by the monk Eadfrith circa 700CE, as the great exemplar of this age of opening and innovation. We encountered a beautiful facsimile copy of this important artefact, which was one of the first illuminated books to be produced in Europe, at Chester-le-Street in the place where St. Cuthbert’s body lay for 112 years before being taken finally to Durham as safety against the Danes – a reminder that times were dangerous. We could also see the 10th-century ‘gloss’ written by Aldred the Scribe inserted between the lines of Latin text, translating it into an early form of Old English. So this one document (the original of which is held at the British Library [/]) is witness to two major transitions: firstly, from the Celtic to the Anglo Saxon at a cultural level, and then, 300 years later, the transition from Latin to Old English, this being the first known translation of the New Testament into English.

The power of even the facsimile, beautifully made from vellum and original pigments, was quite a surprise. It was a very evident demonstration of the truth of Seamus Heaney’s famous statement that “the imaginative transformation of human life is the means by which we can most truly grasp and comprehend it”. Alex Danchev, the military historian and biographer of Cézanne and Braque, also saw artists as ‘witnesses’. In his review of Anselm Kieffer’s 2014 retrospective at the Royal Academy, he perceptively wrote [/] that:

Contrary to popular belief, it is given to artists, not to politicians, to create a new world order.

Perhaps the most thought-provoking occasion of our journey ‘in the footsteps of St Cuthbert’ was arriving at the remains of the Monkwearmouth-St. Paul’s Abbey in Jarrow, near modern-day Newcastle-upon-Tyne, “”by chance” exactly 1300 years to the day [/] of its foundation by Abbot Coelfrith. Coelfrith was the mentor and educator of The Venerable Bede (672–735), who came to his monastery as a young boy of about eight. At one point, the plague swept through the community and took everybody, apart from the boy and the abbot. In despair, they gave up saying their daily offices, which was the essential work of the monastery. However, after a week, they could stand their sadness no more, and started saying the daily services together. They had nothing to prove, nothing to sell, nothing to gain – they did it for love in love by love. Bede went on to write The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, and his lifework was to make the Latin and Greek writings of the early Church Fathers accessible to Anglo Saxons. His achievements, building upon the work of Coelfrith, made Jarrow a great European centre of learning, and in 1899, he become a ‘Doctor of the Church’– the only native of Great Britain to be granted this honour

The Egyptian to Greek Transition

The Anglo-Saxon world, despite its glorious achievements, had limited artwork and architecture to pass on as evidence of its flowering – much was made in wood that has not survived. By contrast, the transition between the Greek and Egyptian worlds between 600 BCE and the arrival of the Romans at the turn of the millenium, created an artistic explosion, the fruits of which can be witnessed until the end of November in the British Museum’s exhibition “Sunken Cities – Egypt’s Lost Worlds [/]”.

The Nile delta created the setting for the establishment of trading links, cultural interchange and political power that has only recently been discovered, and painstakingly excavated from beneath the seabed near Alexandria. These objects represent not just the ‘sunken cities’ of Canopus and Thonis-Heracleion, but a whole new cultural world order whereby the genius of the Greeks was allied with the mystery, power, longevity and organisation of the Egyptians. The history is quite remarkable – not only of the place itself but also of its discovery, and the efforts and technology used to recover thousands of extraordinary objects.

So how did this transition take place? The exhibition makes it clear that trade was central, as evidenced by the remarkable pair of stone stelae known as “The Decree of Sais” – shown above and on the cover page of this issue – that were made during the reign of Pharaoh Nectanebo (ca. 380 BC). This decree highlights not only the taxation requirements, but also the dependence of the Egyptians upon foreign imports of gold, silver and timber of which they had little. This helped Greece grow in political strength and in due course impose its will on Egypt – most notably when Alexander the Great conquered the country in 332 BC, in an almost bloodless annexation from the Persian Empire which had ruled through surrogates for 200 years previously. After Alexander was installed as the new pharaoh [/], he attended lectures given by the Egyptian philosopher Psammon, agreeing with his teaching that “all men are ruled by god, because in every case that element which imposes itself and achieves mastery is divine”.

That this was a civilisation founded on fusion is clearly shown by the fact that the Greeks and Egyptians shared a common pantheon of gods and goddesses; Heroditus, the 5th-century BCE historian, is quoted as saying, “Nearly all the names of the gods came to Greece from Egypt”. The remarkable Statue of Arsinoe II from Canopus elicits a gasp of amazement when seen “in the flesh”. Arsinoe was the sister and wife of Ptolomy II and was raised to the level of the goddess Aphrodite in her own right. She was also sometimes associated with Isis; the pharaohs and their queens embodied the myth of Osiris and Isis throughout Egyptian history, and both Alexander and the Ptolemys, who reigned after his death, continued this practice. The excellent catalogue (that will still be available when the British Museum closes its doors on the exhibition) describes the statue as follows:

The sculpture represents the queen as an incarnation of Aphrodite, the goddess of beauty believed to grant “fortunate sailing”. The surface of the black, hard stone has been rubbed to achieve a polished appearance. The striding pose is rather traditional and formal, but the masterful wet drapery provides vitality to the composition. […] The long pleated dress, which leaves her shoulders bare, and the shawl knotted above her left breast embrace tightly the curves of her body. The sensual rendering of her flesh is revealed through the play of the transparent garment. The style is reminiscent of Greek masterpieces from the 5th century […] which show a similar treatment of the fine, clinging drapery.

Another beautiful exhibit is a life-size statue of the Apis Bull which is also closely identified with both Osiris and the capital Memphis. There are several smaller Apis statuettes in the exhibition, but this one comes from the reign of the Roman Emperor Hadrian (r.117–38 CE) in black diorite stone. It represents power and majesty closely allied to kingship, while being crowned with the sun disc and sacred cobra rearing between his horns indicates the divine source, and ultimate return, of these attributes.

On his arrival in Egypt, Alexander made sacrifices to Apis and held a Greek-style games and literary festival in celebration. These cemented the bonds between Greece and Egypt, which were to successfully co-exist for 300 years. Great cultural centres were established, in particular the library at Alexandria, which held works on geography, history, mathematics, astronomy and medicine as well as literature. It was founded by Alexander’s general Ptolemy I and continued until its gradual destruction over what is thought to be a period of many centuries rather than as a single event; when Muslim forces took the city in the 7th century CE, there were few traces left of the great collections.

In the 1st century CE, further developments in religion and philosophy took place in the Nile Delta with the emergence of what we call “The Alexandrian School”, which combined Jewish theology, Greek philosophy and mysticism into a new synthesis known as Neo-platonism. This in turn influenced the early Christian church through Clement of Alexandria, Origen and others, some of whose works, as we have already mentioned, would later be held in the ample monastic library at Jarrow. So we can plot the influence of religious ideas from Egypt to Greece, and the return of those ideas reformulated by philosophy to create a new synthesis, which in turn developed further as the civilisation drew in new elements.

The Transition into Tomorrow, continued…

The changes presaged by the data revolution, as described by Harari in Homo Deus, may be as devastating to humanity as invaders, plague and famine were to the Anglo Saxons of Northumberland and the Egyptians of the Nile Delta. Similar to these scourges of civilisation, data-ism, and its apparently softer side, “techno-humanism”, are both characterised by a lack of compassion. “Techno-humanism” pretends compassion by appearing caring, but only insofar as it wishes to “hoover-up” the minutiae of life and make individuals slaves to a marketing matrix. As Harari says:

In the high days of European imperialism, conquistadors and merchants bought entire islands and countries in exchange for coloured beads. In the twenty-first century our personal data is probably the most valuable resource that most humans have to offer, and we are giving it to tech giants in exchange for email services and funny cat videos.

He warns us of the dangers of the path that we are heading down precipitously, where humans may become redundant like the horses and other beasts of burden, which performed all working tasks until the development of engines (whose efficiency is of course still expressed in horse-power). But is this the world we want to live in? Are there alternatives if we do not accept what Harari says about the inevitability of technological supremacy? What of the other levels of being that are present in humanity – those expanded by the Greeks, and discovered by the Church Fathers and their antecedents, and their descendants, including the great saints of Northumberland.

This contemplation of previous transitions leads me to regard the past not just as a heap of outmoded algorithms, but a valuable resource to be archeologically unpicked and valued, in the same way that our DNA might be by a geneticist. After all, we all share individually in our collective history. The amazing civilisation in the Nile Delta absorbed many overlapping layers of experience – trade, politics and power, religion, philosophy and culture – coming together as an expression of humanity which resulted in new forms and insights that progressed humanity as a whole.

We too, in the 21st century, are in need of a renaissance that values the breadth and depth of the human experience and does not reduce it down to data bits. Harari himself has been a practitioner of Vipassana meditation for many years, since his Oxford days, so presumably has learnt at first hand the difficulties of controlling the left-hand side of the brain. This has a tendency to explain and promote its existence through fabricated narratives, which are quite correctly identified by Buddhists and data-ists alike as illusory. Maybe data-ism itself is just such an illusion? Perhaps we must look to the new shamans – the “witness-artists” – to pluck the creative forms from behind the veil of the surface illusion and bring them out. And perhaps we also need to “fast” from our devices from time to time, and attend to ourselves and to each other in love and service, if we are to retain a sense of who we are and free ourselves from the need for any “ism” whatsoever.

Image Sources (click to open)

All images from Sunken Cities courtesy of the British Museum.

Other Sources (click to open)

A video of Harari’s talk on September 8 is at https://www.thersa.org/events/2016/09/a-brief-history-of-tomorrow

YUVAL NOAH HARARI: Homus Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow, Harvill Secker, London 2016.

STEVE LOHR: Data-ism: Inside the Big Data Revolution, Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2015.

FRANCIS FUKUYAMA: The End of History and the Last Man, 1992, Penguin edn 2012.

MELVYN BRAGG’s series on Radio 4 “The Matter of North” is available from BBC i-player: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b07tczl3/episodes/downloads

ALEX DANCHEV’s review of Anselm Kieffer’s 2014 retrospective at the Royal Academy can be found on https://www.timeshighereducation.com/features/culture/anselm-kiefer-at-the-royal-academy-cataclysmic-transformational-stupendous/2016079.article

The British Museum catalogue entitled Sunken Cities; Egypt’s Lost Worlds, eds. Franck Goddio and Aurelia Masson-Berghoff, was published by Thames & Hudson, London, 2016.

This article is dedicated to Alex Danchev [/],

who died aged 60 on August 11, 2016

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READERS’ COMMENTS

0 Comments