Arts & Literature _|_ Issue 9, 2018

PAINTING AND THE CONTEMPLATIVE LIFE

Artist and psychotherapist Benet Haughton talks about the spiritual vision that underpins his life and work

PAINTING AND THE CONTEMPLATIVE LIFE

Artist and psychotherapist Benet Haughton talks about the spiritual vision that underpins his life and work

“Keep it simple and do it with love”. This is how Benet Haughton heads up his own reflections on his life as an artist on his website. The son of the well-known Christian theologian Rosemary Haughton, Benet and his family spent many years founding and developing Lothlorien, a community in Galloway, Scotland, dedicated to the arts, healing, and an ecologically sound way of living. Since 1984, he has lived in Edinburgh, dividing his time between painting and his work as a psychotherapist. In a rare interview, he talks to Jim Griffin about the people who have inspired him, the tension between contemplation and action in his life, and the process of painting in the 21st century.

Jim: Perhaps we could start with some of your family background, and what it was that drew you towards painting. Were there any particular family influences?

Jim: Perhaps we could start with some of your family background, and what it was that drew you towards painting. Were there any particular family influences?

Benet: My maternal grandfather, Peter Luling, was a painter, quite a well-known one in fact. I discovered recently that he has some work in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. So painting was there in the family. I remember going around the National Gallery with my grandmother when I was about seven, looking at the great masters, wondering what on earth they all meant. But something went in somewhere. Then my mum, Rosemary, when I was about eight, gave me her oil paints. It was an old box with brushes, a whole load of oils and a palette. I think she had decided she didn’t want to paint any more, or didn’t have the time; she was too busy writing.

Jim: Had she painted previously?

Benet: Yes, she was at the Slade School of Art. She was gifted and – I learnt this from my dad later on – when they met at Cambridge, she painted murals on the walls of his digs. She was very energetic.

I think the gift of her paints was a kind of seminal thing, a bit like Picasso’s father handing over his palette to his son, saying: “take it over”. Not as profound in my case perhaps, but it was very important for me to be given her box of colours. I remember falling in love with those colours, getting the cadmium and the yellow out.

Jim: There’s such a strong focus on colour in your work, perhaps stemming from that very early attraction.

Benet: Yes, looking back, I think that is true. But it wasn’t any kind of abstract thing, rather something romantic and spiritual, associated later in my mind with Chagall. I remember seeing a book on Chagall, illustrations of his work, and absolutely falling in love with it, particularly his wonderful sensuous colour.

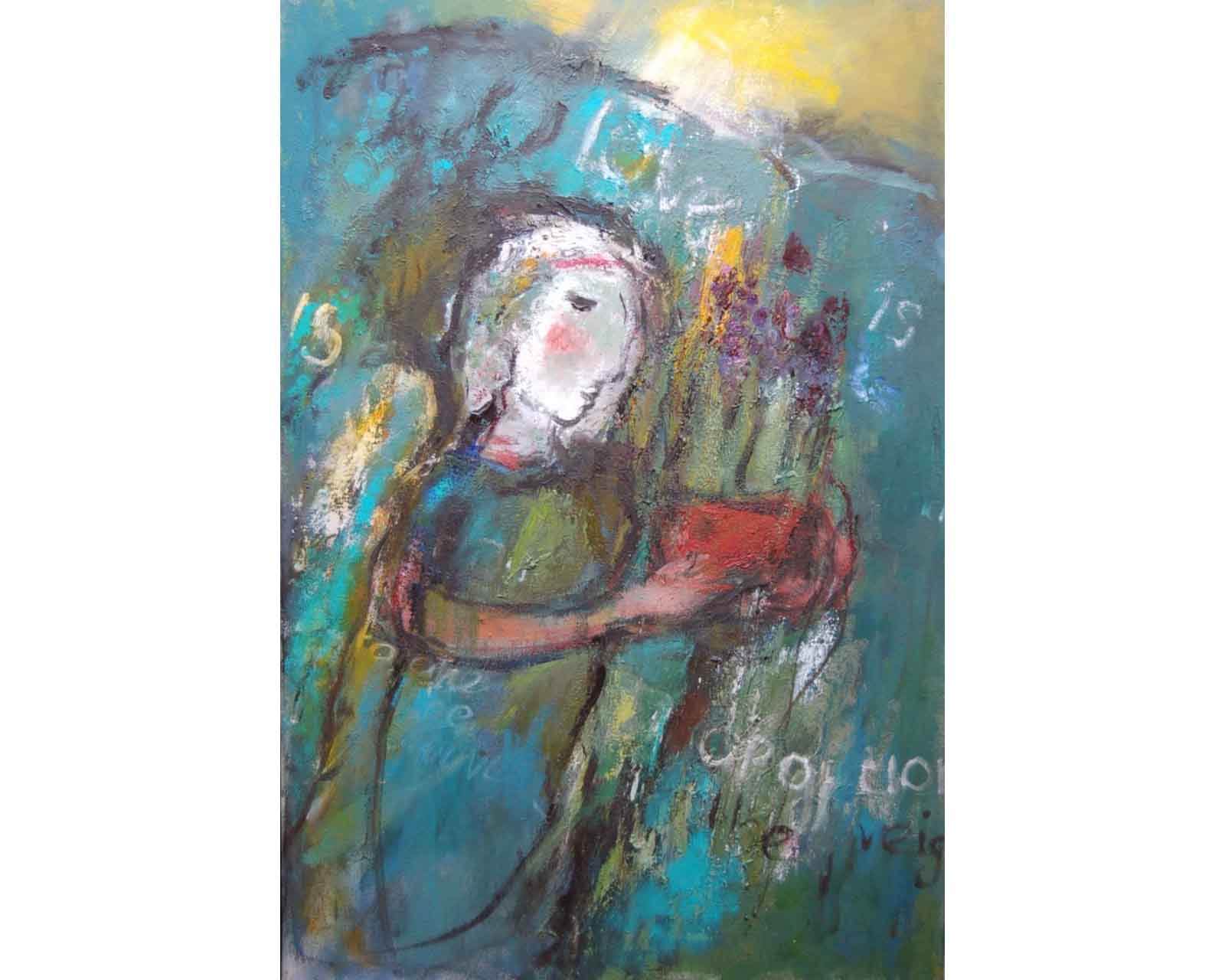

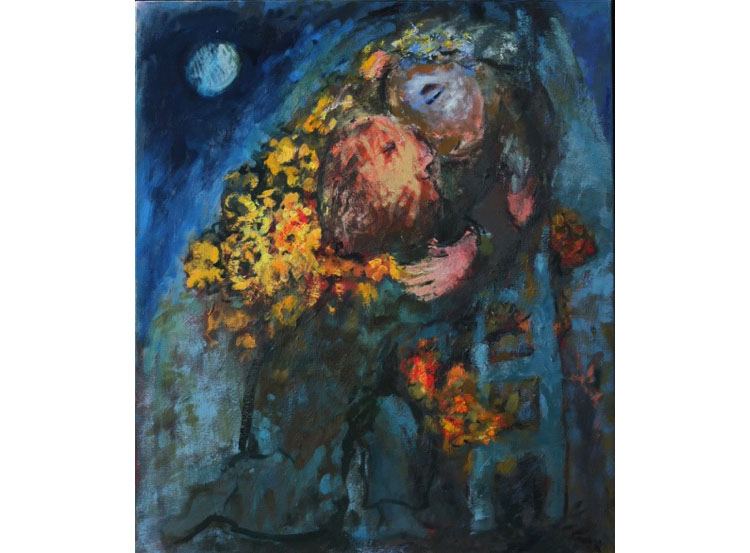

Angel Bearing Flowers (Oil on canvas, 36” x 22”, 2011). See Benet’s introduction [/] to his angel paintings

Jim: This link with Chagall was made while you were still young, before you went off to college?

Benet: Oh yes, well before; I was about thirteen at the time. And then at school I painted; I did very little else but paint, and loved it. I painted prolifically and had a couple of in-house school exhibitions. And then – a bit like my mum really, it’s funny how we repeat these generational things – I gave it all up in about 1974. This happened because we had moved to Lothlorien; I had a family, and we were involved in the community. So although I was passionate about painting, I felt it wasn’t what I should be doing, that I should devote myself to my family and to building up this community.

Jim: You say “should”. Where did that imperative come from, to give your life to something else?

Benet: That’s an interesting point. My mother was very moral, very visionary, and I absorbed a lot of that. When we went to Lothlorien, my mother was really in her prime, and she said: “We’re going to do this. We’re going to build a basic Christian community”. The aim was to create a space where people could stay, and learn the arts, and involve themselves in ecology, in farming. It was going to be a big thing.

Jim: And this was her vision in particular?

Benet: Yes, it was very much her vision, although it was discussed with my dad. I think now, speaking psychologically, that this was also unconsciously a way of saying, “Maybe we can make our family life better” because there had been problems. My dad drank, there was lots of stuff going on, and it was difficult at times, as well as being very rich and lively.

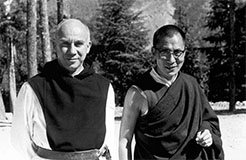

Thomas Merton once put it like this: “People with strict mothers become contemplatives”. Well, I’ve thought about that phrase off and on, and I think I totter on the edge of being a contemplative.

Jim: It’s very interesting that you mention Thomas Merton. I remember reading in one of his journals that he had just been visited for the first time by a pregnant theologian, and later found out that it was in fact your mother, carrying one of your siblings.

Benet: Yes, that’s right, my youngest sister, Emma.

Jim: I think this contemplative strand is really important. How do you balance the contemplative side of your life with the active side that says I must go out, I must work, I must build? There is clearly a great tension between the two.

Benet: Yes; although now I feel I am getting to a point in my life where I can say, “I’ve worked enough as a psychotherapist and I can give myself now to painting.” So I feel the active side is now giving way to the contemplative. But where that will lead I don’t know.

Painting the Bindi on Jesus (oil on paper, 39.5” x 29″, 2005). See Benet’s introduction [/] to this painting – see also Image Sources at the end of the article

Jim: It seems to me that what’s so important here is beauty. Your works really celebrate beauty – the beauty of images, of colour – and alongside that is your use of archetypal images that can trigger all sorts of responses in people. That’s a tremendous gift to be able to give to others. But it takes the process of contemplative withdrawal for that gift to emerge: to withdraw into the studio, to immerse yourself in the colour and the smell of oils – but I take the point. There’s another voice that says, “Maybe I should be out there doing something; maybe starting another Lothlorien, or something like that.”

Benet: I get so much nourishment from painting, but I do ask myself whether it’s justified in a world that is so marked by conflict, division and misery. But a friend said to me: “Well, if your paintings give people joy, and provide a window into something else, isn’t that important?” And actually I believe that utterly.

I’m working at the moment as a kind of mentor to a young woman involved in clowning, slapstick, comedy, nuttiness – and I say the same to her: you must do this, it brings so much joy. And we need to do it all with compassion, because that’s what people need.

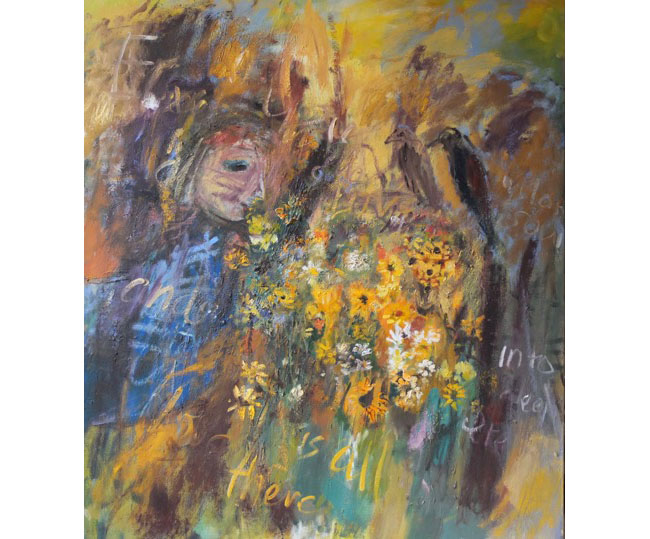

Love is all there is (Oil on canvas, 48” x 42”, 2012)

The Lothlorien Community

Jim: Having mentioned Lothlorien, could you say a little about that whole project and how you got involved?

Benet: Yes. I’d been at college in London, studying teacher training with art as my subject. It was about the time of the first Club of Rome report [/]. So, in about 1972, my wife Kaaren and I, along with other friends in London, were very exercised by the question of growth, the exponential use of the planet’s resources and so on. Many people were talking about getting away from the city, but in the end we were the only ones amongst our friends actually to get out of London. The aim was to start a community, an educational project. There were examples of other community ventures at the time, Laurieston Hall [/] for instance, and lots of other small groups. Also it was the time after the Second Vatican Council [/], when there was a strong move towards basic Christian communities, people wanting to live simpler lives and reconnect with fundamental values, with the natural world, with work that had meaning.

In the end, Lothlorien quickly morphed into something different: a place which offered help to people – unemployed people, people suffering from depression, single-parent families. We met a Dominican priest, Anthony Ross [/], (Order of preachers, OP), who was Rector of Edinburgh University as well as founder of The Cyrenian charity in Edinburgh in 1968. He joined us and supported our venture. So the idea emerged of becoming a therapeutic community, offering help to kids and adults, to isolated youngsters, people with drug problems. During the early period, 1974–77, we remained a Christian community; there was a meditation room and we were focussed on core Christian values. But later in the seventies this specifically Christian element disappeared and we became simply a therapeutic community. And this threw up a whole load of issues. We sometimes felt a bit out of our depth, and so in the early eighties, I became interested in the idea of training as a psychotherapist.

So yes, we were a community consisting of family and friends, some of my siblings (I was one of ten children), trustees – all trying to live together. But not just living together: we were also building a house, creating a smallholding, making a garden on very unpromising soil.

The log cabin at Lothlorien, 1977

Jim: Yes, I think I read somewhere that it was the largest log house in Britain at the time.

Benet: Yes it was 90 foot by 30 foot, built over three storeys.

Jim: And you were part of the construction team?

Benet: I was the main manager, the driver behind getting materials, working with architects, co-ordinating the many volunteers who came to work, because many people had heard about Rosemary and what we were trying to do. Every summer we put up a huge canvas tent, and we would all eat there gathered round a long table. The food was cooked outside, as the house didn’t yet have a roof. We spent three summers working and living like this – an amazing life, amazing experience.

Summer work camp at Lothorien in the 1970s.

Jim: I sense a very strong foundation of Christian compassion, a deep-rooted Christian vision, in what you’re talking about, which led you on to seek training in psychotherapy. But it also, perhaps, gave you a number of themes that came out in your painting later on?

Benet: Yes, that has never really left me. I discovered Merton more deeply at Lothlorien: his very profound vision of a contemplative life, of the relationship between contemplation and action, of the participative life and the need to withdraw.

Jim: But then you left Lothlorien to follow a training in psychotherapy. Can you say how that came about?

Benet: Yes, we left Lothlorien in 1984. My father stayed on and my mother moved to the States and started another community – Wellspring House, in Massachusetts. But my father was getting older, becoming tired, so we looked around for a way to hand Lothlorien over. We were in contact with Akong Rinpoche, abbot of the Buddhist monastery at Samye Ling, and he was interested in the project. So in the end, Samye Ling took it over on the basis that it would continue as a therapeutic community. Which it does, even now. They completed the building, and added another – and it flourishes, with a clearer structure these days but with the original spirit remaining. I go down every so often and talk about the origins of the project, the early days.

Jim: This seems a wonderful instance of what some people call ‘the wider ecumenism’ – Lothlorien starting with a Christian ethos, then being taken over by Buddhists, who share a similar ethos of care and compassion. There is no tension or conflict in that, which is remarkable.

Benet: Yes, I suppose it is. But one of the great gifts I’ve inherited from my mum is a sense of openness. Her side of the family was Jewish originally, coming over from Hamburg; while my dad was originally Plymouth Brethren, though he later became Catholic. So there was a coming together of different traditions, and as children we had to learn to manage the disparate strands. Family life was a melting pot – and I guess for me, as the oldest boy and being particularly close to my mum, there was a lot to take on.

But remember that we were growing up in the period after the Second Vatican Council, where the message of the Council was to open our hearts to all; that we can no longer separate ourselves from people simply because they don’t share our beliefs.

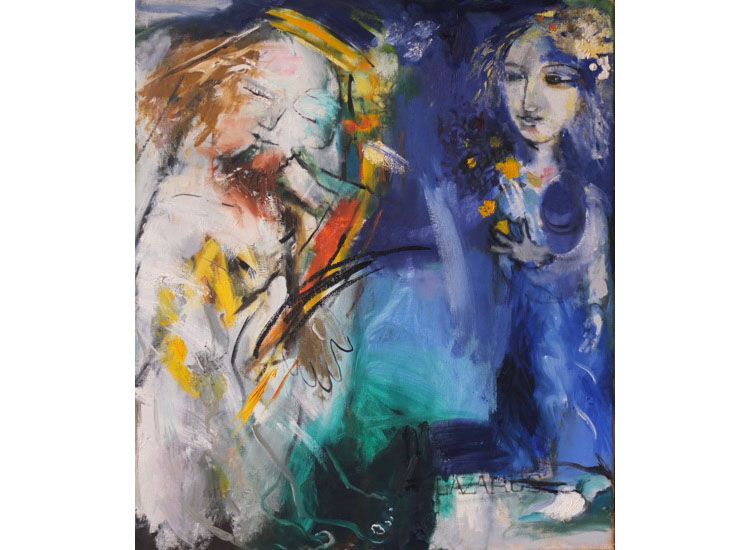

Annunciation (Oil on canvas, 23” x 18”, 1992)

Returning to Painting

Jim: So – you left Lothlorien and started a new professional life in Edinburgh. How did the wish to paint emerge again?

Benet: Well, I went to see a therapist called Steven Briggs, who had a Jungian background. He was quite a character; he used to cycle around town in a white suit. I was actually quite lost in the wake of leaving Lothlorien, and I started to see him in 1987. He said: “Get back into painting” – but not quite as bluntly as that! So I did. And it was as if I’d never stopped. I picked up my brushes, and I found these images emerging that were reminiscent of my early work.

Jim: And when you talk about images emerging, is there a process of gestation, of something going on and then there’s an image that takes shape? Or is it about making marks with charcoal or playing with colour?

Benet: It’s a mystery! I remember when I was about nineteen doing a painting of a couple, both of whom were looking into the wind – looking into the future, their faces being attacked by the rain.

Jim: So would you say that that painting was about yourself in a way – looking into the future, trying to predict a path?

Benet: Yes, in one sense. There’s always been a looking ahead, a searching. There is the wonderful image used by Bede Griffiths [/] of ‘the golden string’ – of pursuing the thread, finding how to stay in touch with it so as to find the inner daemon.

So how do I make a painting? There are probably three ways that I come into it: one is through colour, one is through an idea or inspiration, and another involves using an existing painting which provides a kind of platform. I may have two or three paintings on the go, and I might find when looking at them that I want to kick off in another direction. Nowadays, there are perhaps more concentrated ideas about symbols, on colour and symbols, and the way they interact.

There’s a painter called Ken Kiff [/] whom I admire. One of the things he said was that in the present time we have to take paint seriously as a substance. It’s not about any kind of depiction; it’s about how we bring the energy of a particular colour into the work. I think this is where contemplation comes in.

I’ve also been reading about Christopher le Brun [/], who talks very cogently about how we have to embrace the whole; we have to become open to the energies, to become conduits. Here in the 21st century, we have so many different approaches to painting, so many understandings of painting; so how do we work our way through to something authentic? In the studios where I work there are maybe sixty artists working away, and each of them is a receptacle for the voices of the time we live in. And they’re all different. There is no single strong school today – no impressionism, expressionism, etc. – it’s all much more fragmented.

If you take the art business seriously, you sit in the face of the storm, and you have to find that still place in the heart of it. I read the other day about Leonardo da Vinci, how he would walk all the way across Milan to his studio to put one stroke of paint on his painting, and then walk back home again. That’s a very, very slow build-up in the painting.

Jim: Perhaps we can imagine that the painting was held in mind and heart as he walked backwards and forwards across Milan?

Benet: Yes – and what a luxury of time, what a commitment of time, and also a kind of self-knowledge: that there’s nothing else you have to do but this.

My granddaughter was asking me the other day how long it takes me to do a painting, and I told her that one piece had taken over a year. She said that at school they want her to paint quickly, and she can’t do it. There’s a kind of ‘hurry-up’ attitude these days, an idea that we have to be able to do things quickly. But that is all a lot of nonsense. It’s actually the same in psychotherapy training: it’s like a hothouse, and actually it takes a long time to become a good psychotherapist.

Jim: I’m thinking here of a couple of analogies. Athletes – particularly distance runners – talk about the experience of ‘getting into the zone’; that after a certain number of miles everything seems to take on an ease, a fluidity, clear-mindedness, as if you could go on for ever. And also, there is an interest today in various ‘slow’ movements, particularly slow food, slow cooking, which allow time for things to mature, developing a proper appreciation.

Benet: Yes. But then there are times when I do things quite fast. I did a whole series of drawings the other day, preparations for a big canvas that is emerging in my mind.

Jim: So would you say that this process is about acknowledging your own rhythm – not externally imposed – allowing both slowness and speed?

Benet: Absolutely, and this requires a commitment to self-awareness, to meditation, making time for discovery; and being willing to hunker down into that space until something emerges. For me there is always a time lag with painting. I work two days a week at psychotherapy, and on Wednesdays, when I move into painting, there’s always a transition into a kind of quietness.

Raising Lazarus (Oil on canvas, 30” x 26”, 2001)

Symbols and Themes

Jim: You use a lot of symbolic forms and, like Chagall, a lot of biblical imagery. What particular symbols are you drawn to?

Benet: I did a painting years ago of the sacrifice of Isaac [/] and it still resonates for me. I feel that it ties up with questions of our own humanity, of how we sacrifice our children on the altar of our own ideas, and how at that particular moment when Abraham realised what he was doing, he drew back. How do we find a way – through the sacrifice of Christ, for instance – of pulling back to something that is more compassionate, more tolerant and forgiving? How do we look at ourselves in the light of our shared vulnerability, our complex tendencies to make things go wrong?

But that doesn’t really answer your question about symbolism. I use a lot of boats, a lot of ladders, moons, a lot of female (and male) figures, which express both psychological and spiritual realities. I try to bring these two things together in my paintings.

Jim: One thing that strikes me about the faces of female figures in your paintings is that they seem somewhat, well, archaic – as if the figure has stepped from a more ancient kind of world. They’re not representations, but they remind us of a deeper dimension of ourselves, below the day-to-day reality of being a person.

Benet: People have said that to me before, that there’s a kind of primitive quality. Sometimes, not maybe so much now; it’s perhaps a bit like Giacometti, who when he was in his studio and working, say, on a portrait of Diego, his brother would scrub it out, saying “Oh, that’s rubbish”. Sometimes I can go over and over a face or image and the whole thing works, and I can find a way through; something emerges and I can say “Oh yes, OK, it’s enough”. But often it’s not.

In fact, often – like Ken Kiff actually – I’ve destroyed paintings that are quite acceptable to other people. It’s not enough to say that something might be OK in the eyes of others. Kaaren always says to me, “Put them aside. Leave them in the corner. Don’t look at them for a year.” Sometimes I manage that. But quite often I’m on the track or the trail of something. It’s to do with finding a kind of translucence, finding a way through which reveals something, some meaning I haven’t found in an ordinary academic piece of painting. Something has to come through that I haven’t seen before, that is transformative, so that I’m surprised, genuinely surprised, by it. It might be only a small thing, but then I can say “Aha!”. And when I get to that place, I know that I’ve hit the jackpot, I can let it rest.

Jim: I like the word ‘translucent’. It reminds me of a poem by Edwin Muir called ‘The Transfiguration [/]’, which is about the story of the transfiguration in the Gospel. In particular, it is about the way in which the whole world, for a time, is transfigured in the vision of Jesus’s disciples. Something shines through.

Our hands made new to handle holy things,

The source of all our seeing rinsed and cleansed

Till earth and light and water entering there

Gave back to us the clear unfallen world.

This sense of the transfigured world is also central in the iconography of Orthodox Christianity. It sounds to me that that is what you are looking for, that moment of transfiguration or translucence. You’re smiling, and I wonder why… Is it because I’m on the right track?

Benet: I am smiling, and it is because you’re absolutely on the right track. This goes back to the question of paint and symbols, and how to show symbols on a two-dimensional surface. They cannot slap you in the face, as in a lot of art in the past, because that is not our sensibility now. We need to be wooed… We need to be wooed by beauty, and having been wooed, we then need to be able to listen again to something which has perhaps become worn out and clichéd.

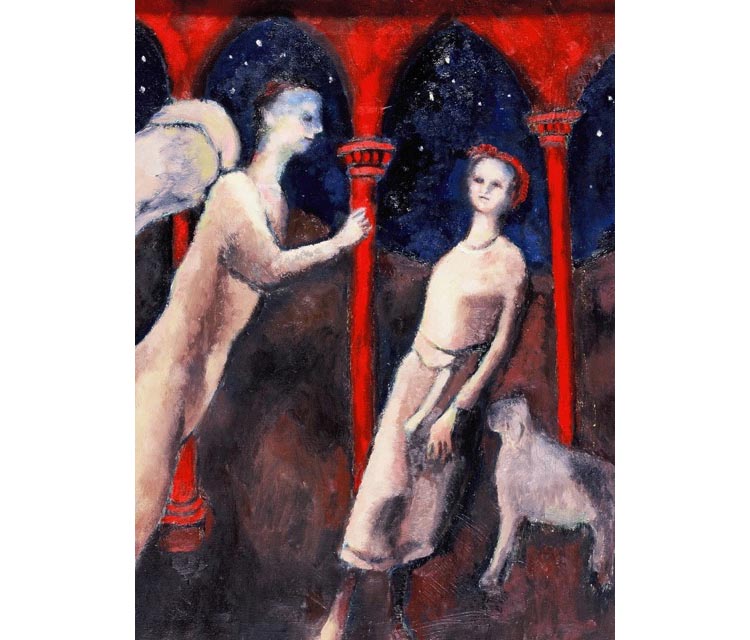

Jacob’s Dream (Oil on canvas, 30” x 24”, 2018)

Jim: By things that are ‘worn out and clichéd’, I take it that you are referring particularly to the stories of the Bible?

Benet: Yes. I’m working with ideas of ladders and chalices at the moment, and also forms, spherical forms. So I’m thinking about joining up worlds by ladders, and about the story of the prophet Jacob. I’ve done quite a number of paintings of Jacob and the angel [/], and now I think I have to be very clear in my own head about what I’m saying. But I also have to put something in there that’s beautiful. And that brings up thoughts about paint, about the use of the paint, the juiciness of the paint, the way it will stand up, the quality of the surface, the texture, whether it’s matt or shiny, whether the paint drips. So I’m playing a lot with the tactile nature of the medium.

Jim: So what are the next steps, do you think?

Benet: I’m looking forward, God willing, to having more time to paint, as I’m coming to the end of my psychotherapy career, and painting will then take over. I feel that I’m beginning to move into a new phase in the work. My mind has always been absorbed in a kind of Chagall-esque approach to colour, but there are other painters who have influenced me as well. One of them is Arthur Boyd [/], an Australian, a wonderful painter who came to prominence in this country, lived over here for a long time. He painted on aboriginal themes, beautiful work; again very close to Chagall, I love his colour and his lines. And then more recently there is Cy Twombly [/], an American whose work is a kind of offshoot of abstract expressionism with its own lyrical poetic feel and ideas. It’s wonderful the way he plays with his material; he uses lots of different kinds of materials in a single painting – crayons and chalks and oil paints, pencils – a whole gamut of things, very exciting.

Jim: So you’re in a transition now to – well – you don’t know, as you said before … it’s a mystery. But you’re opening up to something.

Benet: Yes, though honestly I feel I’m permanently in transit. This is where we come back to the contemplative state, being in a state where I can just sit, and remember that there is continuity in life. It’s not just happening moment by moment: there is a pattern. So I would say that there’s definitely something new emerging.

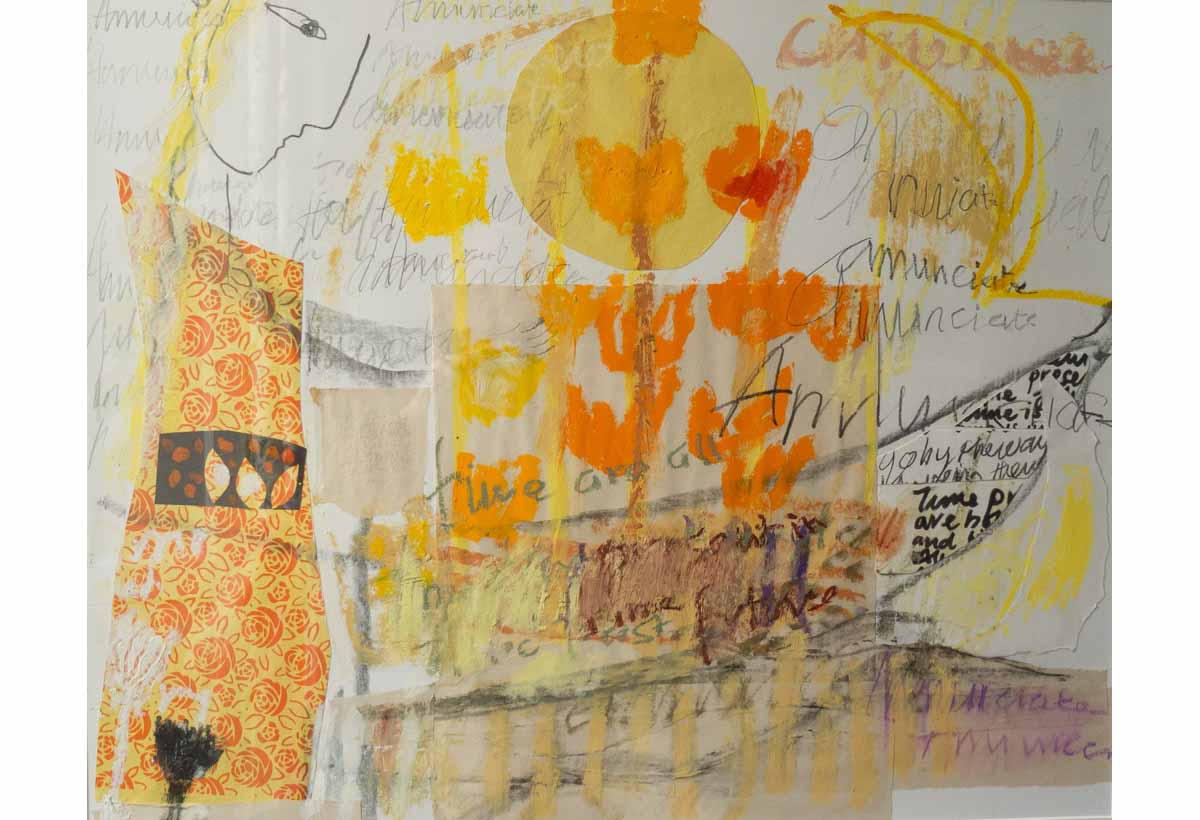

Annunciate (Mixed media on paper, 27.5” x 23.5”, 2017)

An exhibition, ‘Homecoming: The Art of Benet Haughton’ will be taking place at The Cornucopia Room, 4 Towerdykeside, Hawick TD9 9EA, from May 12th–June 3rd 2018. For more information, see: http://www.cornucopia.net/events/homecoming-the-art-of-benet-haughton/

For Benet’s own website, with many examples of his paintings, see: http://benethaughton.co.uk

Image Sources (click to open)

All images courtesy of Benet Haughton

Banner: Detail from Painting the Bindi on Jesus (oil on paper, 39.5” x 29″, 2005)

Benet says of this painting:

“I painted this back in 2005 and could have sold it to someone then but felt unable to let go of it. I still have it on the wall in my home. A few preliminary ideas had come to me. I had always been attracted to the idea of the painter depicting himself in the act of painting. It is a tradition going far back in Western art. But the idea of the artist painting the Bindi on Jesus was as far as I know entirely my own idea. It came to me as an inspiration, a kind of consecration of the business of my being a painter. I was being blessed by Jesus who is my seeing, clear sighted self! (The Bindi of the Hindu faith is the small red dot that is placed between the eyes and signifies access to the sixth chakra, the seat of “concealed wisdom” or the third eye.) So there is a virtuous cycle in the painting between the two figures each blessing the other; my self with my brush and Jesus with his acknowledgement that he is fine with this. It was a turning point in my work as it worked on more or less every level at once: composition colour balance, and subject matter all met in it.” See http://benethaughton.co.uk/paintings/painting-the-bindi-on-jesus/

First Inset Image: Benet Haughton

Other Sources (click to open)

“Keep it simple and do it with love” quote by Robert Colquhoun

Rosemary Haughton:

The Passionate God (new edition, Anglico Press, 2013)

The Transformation of Man; a study of conversion and community (Geoffrey Chapman, 1967)

Love (Penguin, 1974)

Thomas Merton: The Other side of the Mountain: The Journals of Thomas Merton, Volume Seven 1967-1968 (Harper San Francisco, new edition 1999). Reference to Rosemary Haughton on page 4.

Bede Griffiths The Golden String: An Autobiography (1954: Templegate Publishers, 1980)

Email this page to a friend

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

READERS’ COMMENTS

0 Comments