Arts & Literature _|_ Issue 22, 2022

George Swede: Haiku Master & Secular Contemplative

Robert Hirschfield talks to the Canadian poet and psychologist

George Swede: Haiku Master & Secular Contemplative

Robert Hirschfield talks to the Canadian poet and psychologist

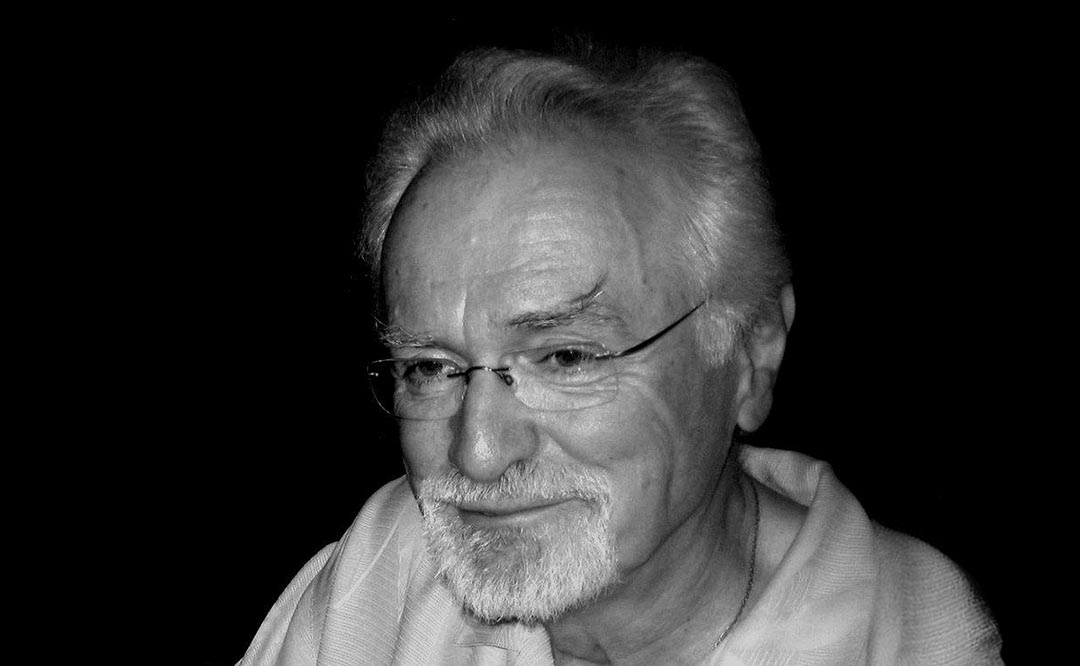

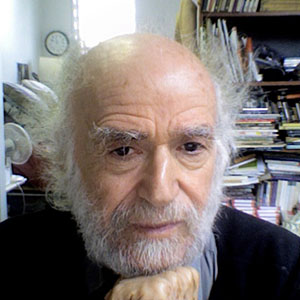

George Swede (Latvian: Juris Śvēde) is a psychologist, poet and children’s writer who lives in Toronto, Canada. He is a prolific and widely-published writer of English-language haiku, known for his quiet, wry observation of the world. In this article, Robert Hirschfield presents his work and talks to him about his understanding of the haiku form.

the game with

seven billion players

one ball

He kidded me in an email about being an octogenarian writer writing about an octogenarian writer. Someone else might have been tempted to add a cautionary punch line – maybe something about the wisdom of planting an orange grove in death’s waiting room.

But instead of words there was empty space. A contemporary haiku master, George Swede [/] (aged 81, born in Latvia in 1940) has published over 40 poetry volumes, mostly haiku. His work has been translated into 23 languages, and written about in countries as far-flung as Portugal and Japan. One might label him an exporter of empty space hitched to precisely chosen handfuls of words.

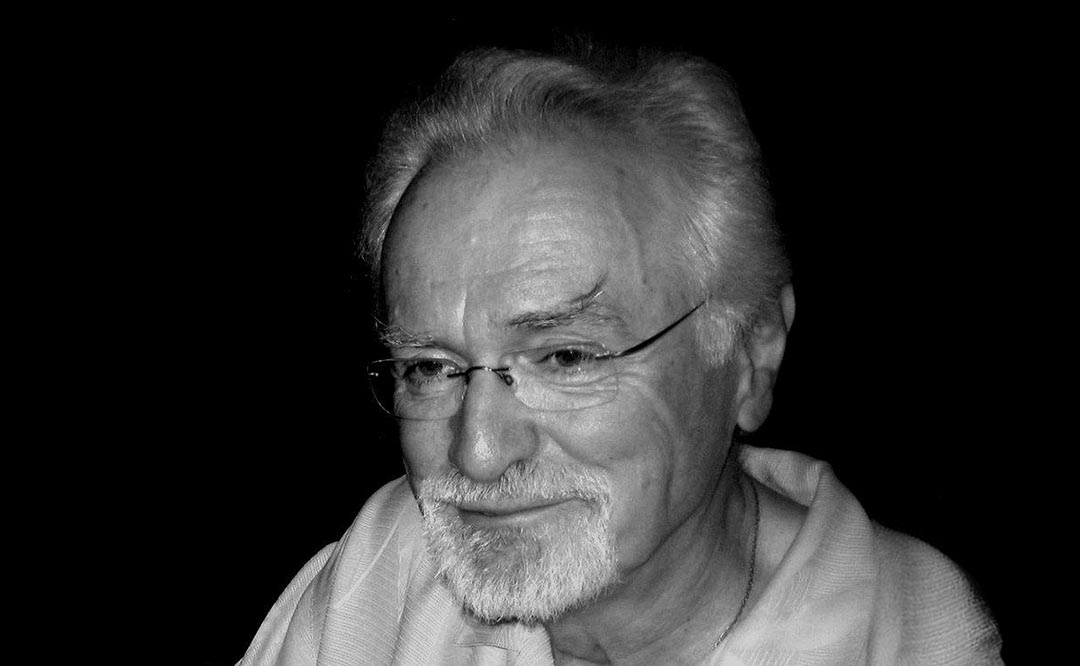

In haiku, the empty space that spills from each line is a charged place holding the rendered moment in a kind of timelessness. From Basho’s sanctified old frog in its frog pond, I one day found myself contemplating this astonishing early offering:

At dawn thinking of her bad grammar

Was Swede impishly transgressing the gravitas of the hour? Throwing light on the mind’s inherent anarchy? Or simply marking our tendency to transform even sober moments into self-indulgent pirouettes?

Swede has had a life of academic immersion; he got an MA in Psychology at Dalhousie University (Nova Scotia) in 1965, taught at Vancouver Community College in the late sixties, then almost exclusively at Ryerson University until his retirement in 2006. But he has managed to avoid the conditioning of analytical detail. “I have always opted for brevity in all my writing, scholarly or otherwise.”

His haikus follow no train of thought but a line of sight that is all-inclusive. Reading his poetry is a little like being out walking with a man with a PhD in seeing. He will stop from time to time, tap you on the shoulder, and point:

used bookstore

a sunset beam lights a row

of forgotten authors

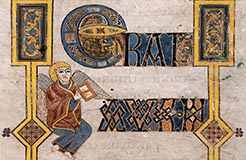

Illustration of a famous haiku by Matsuo Basho (1644–94): Tsuki to Ume (Slowly spring // is taking shape // moon and plum), Endo period (1615–1868). Image: Artokoloro [/] / Alamy Stock Photo

Becoming a Haikuist

.

When I phoned him one afternoon in Toronto, he said in his slow-spoken way, paced with spaces in the style of his haiku: “I have always nurtured a connection with the immediately perceived: in a forest, or in the centre of a large city, or in my study. It seems to give me the grounding necessary to not be overwhelmed by the suffering that surrounds us in its many guises.”

He touched briefly on his childhood in Latvia during the war. The Nazis invaded. There were mass killings. One of those killed was his father. The Red Army also invaded. He escaped with his family in a yellow van at night. He still recalls the pistol on the dashboard. He was seven, and the war was over when he arrived in Western Canada with his mother and his adopted father, Arnold Swede. The poet carried inside him the same unsorted emotional shrapnel that a seven-year-old Ukrainian refugee carries today. The footage we all see of torn up streets and buildings are to Swede the “ruins in which I wandered as a child”.

I wanted to know how he avoided becoming Canada’s first haiku poet in the tradition of Kafka. His answer laid out the visible sections of the long, no doubt hidden path he has walked. “When I arrived in Canada, I lived with my grandparents on their fruit farm. Children my own age lived a mile or two away, so I spent a lot of time alone, especially during the summer. When I finished my chores in the morning, I had the afternoon free to roam with my dog Laddie to a nearby forest and lake, or to open grazing lands with cattle skulls. My step-grandfather, Henry Stoddard, was a gentle, kind person, and his role in my life then was vitally important.”

He went on to tell me the strange story of his transition from free verse poet to haiku poet. In 1974, his first free verse volume, Unwinding,[1] was published. After many printing delays, the publisher arrived with the books in a box – and much fuss – at the Toronto library where Swede was engaged in his book launch.

But the book buyers were a bit mystified by Unwinding’s cover, with its drawing of another poet bearing a faint resemblance to William Faulkner. I remarked that I had heard of children being switched at birth, but never book covers! The poet possessing the book cover intended for Swede died a year later in a road accident.

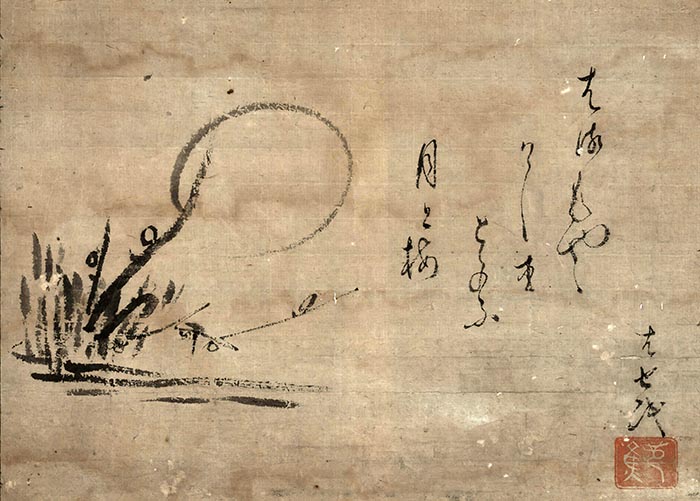

The poet laughed quietly at the egregious error. Redemption came two years later in the form of Makoto Ueda’s Modern Japanese Haiku,[2] a book of profiles and poems by Japan’s late 19th and 20th century reformers led by the brilliant, tubercular Shiki [/]. The group, while not abandoning the tradition-bound season references, controversially injected into their haiku the messiness of human nature that characterises modern life. The poets all ‘spoke’ to him. “I was struck by their brevity, by how much they were able to pack into just a few words. I can relate to this form, I thought. Maybe I can write haiku myself.”

His works immediately began appearing in the Canadian journal Cicada, edited by haikuist Eric Amann.[3] Amman and Swede, together with poet Betty Drevniok, founded Haiku Canada [/], the country’s first haiku society, in 1977. (For more on Cicada, an excellent introduction to haiku by George Swede plus a selection of works by Eric Amann, click here [/].

Representation of Masaoka Shiki (1867–1902) in the Takamatsu Heike Monogatari Wax Museum, Japan. Image: Motokoka [/] via Wikimedia Commons

A Secular Contemplative

.

Swede has rebelled against the Western way of teaching haiku with its stress on the 5-7-5 syllable structure in the standard three-line box. “Japanese haiku have almost always been written in a single line arranged in a column, as the Japanese language flows vertically, not horizontally.” He therefore questions the logic of religiously grafting onto the English-language Japanese haiku’s traditional seventeen syllables. “A 17-syllable Japanese haiku is about 12 syllables in English. The 17 English syllables are seen as too long when translated into Japanese.” Twelve syllables, he muses, would be more appropriate for the devotionally inclined.

Ever since 1978, Swede has been experimenting with ‘micro-haiku’ to illustrate how the form can operate free of line-length mimicry:

leaving my loneliness inside her

and

so much taller

the shrink

when he stands

Or this more recent one, a kind of existential autobiography:

ant bearing a leaf and a question

I came across this comment by Swede in the haiku blog, Red Dragonfly [/]: ‘I think the salient feature of haiku is an almost painfully heightened awareness of some feature of the universe.’

A term came to mind that previously had not occurred to me: ‘secular contemplative’ – one who stands in wonder, wearing whatever occupational clothes he wears, before the simple fact of being, minus divinity. Reading Swede, I realise how much I miss that element in the works I read, in the people I meet, in the life I live. His haiku tends to move the way a day moves: from light to darkness, or sometimes from darkness to light.

in one corner

of the mental patient’s eye

I exist

And this:

the holocaust

grafted onto my rootstock

the temperament of trees

To read more haikus, and other poems, by George Swede, click here [/] for his very engaging Instagram site.

For more information about his publications, see his website www.georgeswede.com

Robert Hirschfield is a New York-based freelance writer and poet who has published many profiles of contemporary poets as well as stories on nonviolence activists in the Middle East, India, Nepal and the US. His work has appeared in Teachers & Writers Magazine, Tricycle, The Writer, The Jerusalem Report, Sojourners and other Publications

Image Sources (click to close)

Banner: George Swede. Image: from https://bashosroad.outlawpoetry.com/george-swede/george-swede/haiku/

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] GEORGE SWEDE, Unwinding (Missing Link Press, 1974).

[2] MAKOTO UEDA, Modern Japanese Haiku (University of Toronto, Scholarly Publishing, 1976).

[3] For more on Cicada and the poetry of Eric Amann, in particular a selection of his verses and an excellent introduction to Haiku by George Swede, see https://thehaikufoundation.org/omeka/items/show/2383

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

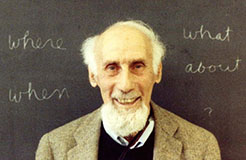

Robert Lax: A Life Slowly Lived

The contemplative practice of a remarkable 20th-century poet/mystic — by Robert Hirschfield

Conversations with Jane Hirshfield

Jane Clark and Barbara Vellacott talk with the distinguished poet about her latest work and the role of poetry in these difficult times

The Book of Kells

James Harpur ‘takes a line for a walk’ as he remembers the challenges of writing his poem ‘Kells’

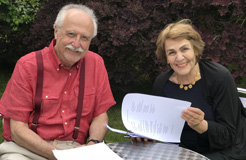

Bewildered by Love and Longing

Michael Sells and Simone Fattal talk about a new translation of Ibn ‘Arabi’s famous cycle of love poems Translation of Desires

READERS’ COMMENTS

I really enjoyed this article, particularly the sample

haiku. My favorite:

used bookstore

a sunset beam lights a row

of forgotten authors

and the single-line (to match how it is in Japanese):

leaving my loneliness inside her