arts & literature _|_ Issue 27, 2024

Giving Voice to the Earth

The distinguished sculptor Emily Young talks about her work and the stories that stone can tell us

Giving Voice to the Earth

The distinguished sculptor Emily Young talks about her work and the stories that stone can tell us

Emily Young has been called ‘Britain’s greatest living stone sculptor’. The winner of numerous awards – the latest being the 2024 Venice Biennale European Cultural Centre Award for Sculpture and Installation – her extraordinary and beautiful pieces can be found both in private collections and public places around the world, including Salisbury Cathedral, Paternoster Square in London and the Loyola University in Chicago. Her aim is to draw out the deep connection between human beings and the natural world, urging us to listen to the tales of time and cosmic change that stones can relate. She spoke to Jane Clark and Pheobe Ryrko by Zoom from her home in Tuscany about the way she works, and the importance of beauty and compassion.

Phoebe: It is clear from your work and some of your writings that you have a very strong and particular relationship with stone. You have described your work as ‘giving voice to the earth’.

Emily: The thing about stone is that it does, literally, embody the history of the planet. And in so doing, it also embodies the history of the solar system, the galaxy and the whole of our universe. The nature of the universe is a debated subject now, with theories of quantum gravity and suchlike, so that I have no idea what reality actually means anymore.

What stone shows us is the great upheavals that happened in the past. They record activities that were going on not merely over millennia but over millions and billions of years – vast volcanic eruptions, ice ages, fierce heats, erosions, floods, enormous tectonic plate movements, huge meteorites. These aren’t tired old things that have nothing to say anymore. They can tell us about how the planet was made, what atoms do when they meet other atoms, where the water was and how much of it was left inside caves making these beautiful, layered stones with sediment which accreted over billions of years that we enjoy now as beautiful creatures, carrying history in their structures and appearance.

Phoebe: It is clear from your work and some of your writings that you have a very strong and particular relationship with stone. You have described your work as ‘giving voice to the earth’.

Phoebe: It is clear from your work and some of your writings that you have a very strong and particular relationship with stone. You have described your work as ‘giving voice to the earth’.

Emily: The thing about stone is that it does, literally, embody the history of the planet. And in so doing, it also embodies the history of the solar system, the galaxy and the whole of our universe. The nature of the universe is a debated subject now, with theories of quantum gravity and suchlike, so that I have no idea what reality actually means anymore.

What stone shows us is the great upheavals that happened in the past. They record activities that were going on not merely over millennia but over millions and billions of years – vast volcanic eruptions, ice ages, fierce heats, erosions, floods, enormous tectonic plate movements, huge meteorites. These aren’t tired old things that have nothing to say anymore. They can tell us about how the planet was made, what atoms do when they meet other atoms, where the water was and how much of it was left inside caves making these beautiful, layered stones with sediment which accreted over billions of years that we enjoy now as beautiful creatures, carrying history in their structures and appearance.

Phoebe: You began your artistic life as a painter and then it seems that stone ‘called’ to you. How did that come about?

Emily: Well, my grandmother was a sculptor; she worked with Rodin. So you could say sculpture was in my blood. It turned out that I always had a strong impulse to find connections with material stuff. It fulfils something in me. The mother/matter thing, perhaps, connecting profoundly, physically, with the world. So I drew and painted all the way through my childhood into my teens. But I didn’t settle very happily into a nice, normal life and started travelling when I was 17, when I ran away overland to India with a young Native American who was escaping the Vietnam war draft in the US. He had a small income from his tribe, the Assiniboine Sioux, and we lived very simply. We headed off to the Himalayas, and then south. I also spent time in the US, drawing all the time.

It was only when I finally came back to England some years later that I had time to paint seriously. I needed to earn a living, so I had some small shows in London and people were kind and bought enough to enable me to get by. I developed quite a good relationship with things – I mean physical things like paint and big sheets of paper, canvas – that could accommodate my thinking and my feelings so that I could transform them into objects.

But then, a few years later, in the house I was living in, in around 1980, I found some little slabs of stone in the garden, which had been left behind when the kitchen worktops had been installed – small slabs of marble. Also, somebody at some point had left a little bag of stone-working tools in a house I had lived in years earlier. I had carried this canvas bag with a hammer and some chisels around ever since, thinking that one day they might come back and collect them. But they never did. So when I found these pieces of marble, I thought: ‘I’ll put these two things together, I’ll just have a go.’ What I loved immediately was the resilience and the resistance of the stone. It was so strong – in many ways, it was stronger than me, which I really liked.

With drawing and painting, there was a sense of being able to move around all over the place, mentally or physically, and you can wipe it away and do it again; I could redo my paintings 20 times in the course of a day. But with stone, you really have to get behind it in terms of physical effort and time in order to make it work, and you’re lucky if you make a serious contribution to the piece in a couple of hours. And then you cannot go back; it’s going to stay there forever, it’s a three-dimensional intervention. You can go in more, but never back.

Emily carving Cautha (2019) near her home in Tuscany, Italy. Photograph: Joshua K. Jara

Connecting with the Earth

.

Jane: But you soon progressed to large pieces of work?

Emily: Yes, I started out doing quite shallow work – reliefs, which are very like drawings. But I quite quickly moved into three-dimensional blocks, and I just worked with whatever I could find around and about. I was going to stone yards and architectural salvage yards where they had blocks of old marble and other types of stone. But I grew annoyed with stones that had had their history removed by being cut into six sided blocks. I felt that I had to work out what to do with these blocks, because the stone wasn’t being allowed to speak in its own voice, to inspire me. I had to listen for their still and silent voice. Turned out it was like food for me. It’s possible to put human consciousness into a piece of stone. That’s the way I felt about it, and this feeling has just got stronger and stronger as time goes on.

Now what I do is find rocks that have fallen out from the hillside here in southern Tuscany, where I live. The countryside is pretty alive and wild here, and the hillside sort of falls open all the time, after rain etc, and the geology is revealed. Many different kinds of stones present themselves; there’s quartzite, marble, sandstones and all sorts of metamorphic stones that were boiled up in the huge volcano which blew up across the land some hundred and sixty thousand years ago. Nearly everything near here is complex.

Jane: So, when you are working, you begin with the rock rather than a conception of what you want to do, and let that dictate the form that emerges?

Emily: Yes, this is the whole matter. With a block of stone that’s cut with six sides, you have to have an idea about what you want to do. This is how most people work; they have a notion that they might make something and model it in plaster or plasticine, then they find a piece of stone that can fulfil their idea. This is what Michelangelo did when he carved the David. But I try not to have any cut sides, so that the stone shows its history, tells something of its story.

Some stones that I use are 3.5 billion years old. There’s a quartz stone in the studio I’m waiting to work with from the northwest coast of Scotland which is some of the oldest on Earth. And a piece of lapis lazuli from Afghanistan is a similar age. This stone has the colour of the richest sky blue you can imagine. Pliny the Elder described lapis as ‘a fragment of the starry vault of heaven’. He also said, ‘the night sky above, lapis below’. Lapis stone is an astonishingly beautiful dark blue stone, speckled with pyrite-like shining stars.

Jane: Thinking about this connection between stones and the celestial sphere, I notice that this is quite a theme of your work. For example, you have carved many beautiful angels – dark angels, wounded angels, archangels – and in every case, you leave some of the stone uncut. We normally think of angels as celestial or ethereal beings, whereas in your sculptures they are emerging out of the earth.

Emily: The word angel comes from the Proto-Indo-European root anjiras which means ‘a messenger from heaven’. When you look deeply into the forms and structures of a piece of stone, as a geologist, or material scientist, it can tell you some of the story of the earth, and how it evolved over these enormous stretches of time. And it will exist for possibly another billion years – who knows how long. By listening to what science tells us about what’s going on outside the earth, in the universe, we also find out more and more and more about what’s happening inside it. The nature of the Earth, of matter. Angels carry trails of heavenly things that manifest as matter to our oh-so-solid flesh.

And the process carries on and becomes an internal sort of discovery about how to be a human. To connect with our earthly home. To be a good human, we probably do need a good relationship with our mother planet. And I deeply enjoy the feeling that comes with making a connection, a rich connection, with the stone, the earth. When I go for a walk in the woods, I feel it’s a good thing to feel that the trees are my brothers and sisters; that we’re made of the same stuff, that we come from the same place. That every single atom is connected to every other atom. It’s an excellent flow area of thought and experience. I can become a voice for the land, which as the poet said, is wettened by falling tears.

Jane: I can see from images of you working that your interaction with the stones is very physical and energetic; you approach them with electric saws and hammers and chisels.

Emily: Yes, I’m working on a bit of stone, and it is speaking back to me, saying: ‘No, you can’t do that – but you can do this’. Stone isn’t passive. It lets me know if what I’m trying for marries well with it. There are certain things I can do and certain things I can’t, but there is also an area in between where I can ask, can I get away with this? I believe if I don’t approach the stone with good intention, it won’t help, can’t help. But then again, it can guide me to areas of stone more complementary to what I bring.

What’s happening when you’re carving a piece of wild stone is that you’re encompassing a wide range of realities, from the rock itself to the most delicate poetic notions of what it is to be a human, and these tie themselves together. The etymology of the word religion is religio which means to tie together, to re-tie.

Warrior Poet (2004), carved from Purbeck blue marble. Installed in Oxford. Photograph: Angelo Plantamura

Move computer mouse over image to enlarge

Warrior Poets

.

Phoebe: Do some pieces feel like boxing partners so that you have to generate fearlessness? And others that are more loving and sensual?

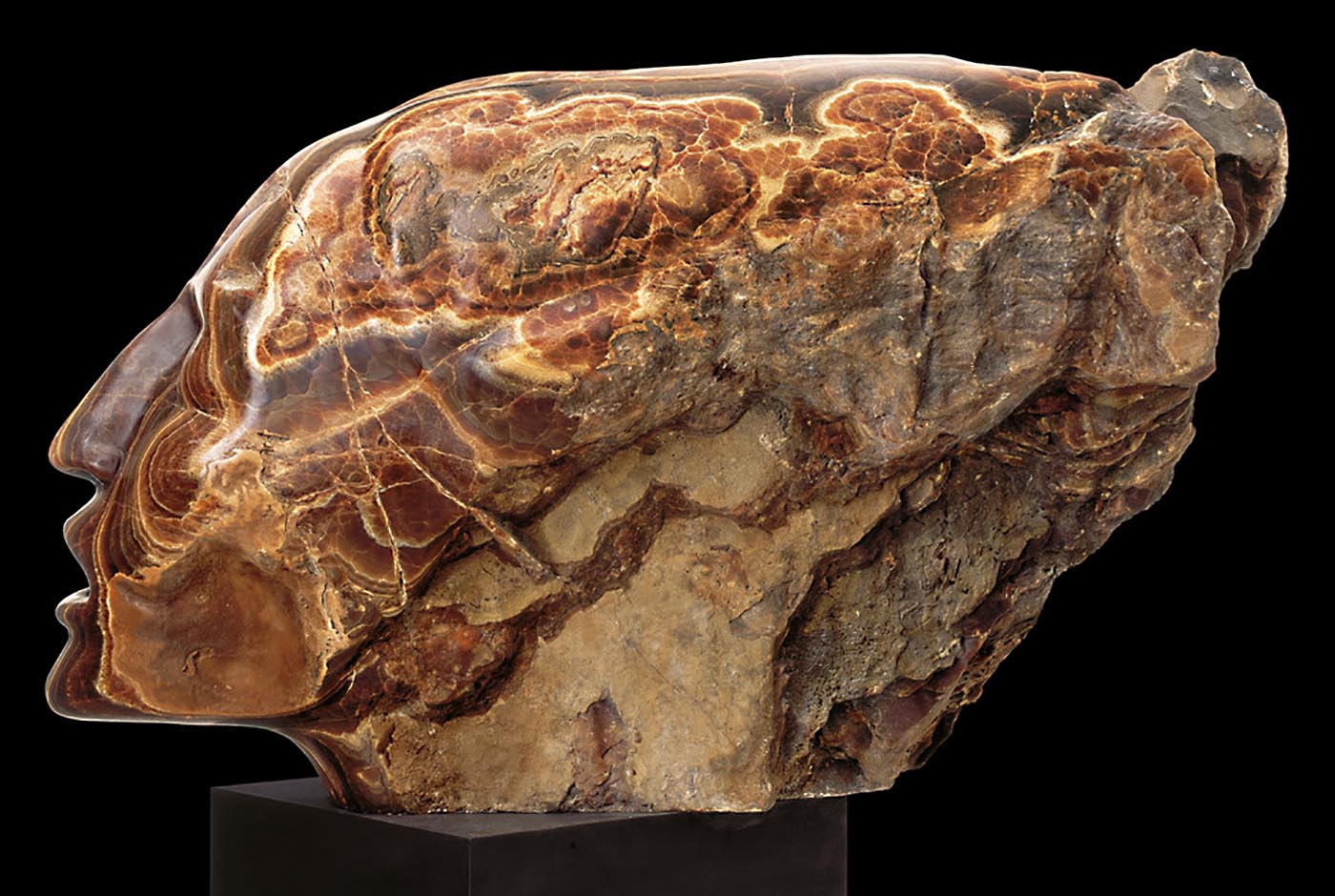

Emily: It’s perhaps not quite that… but something similar. There’s a stone that I work with called anagenite, a quartzite. It’s very hard but it’s also incredibly helpful. It always looks great because it’s largely covered in large crystals that have naturally accumulated; they look like huge tea-coloured diamonds, and they sparkle. I don’t want to fight it, I want to do as little as possible, but I do have to seduce it into allowing me a bit of leeway in making a sculpture. I approach it with respect.

The crystals are beautiful, and carry the piece of stone, aesthetically. I don’t want to lose them. When the rocks first come out of the ground, they are a bit grimy, but I wash them down and say: ‘Well, hello!’ Because it feels as if there’s already somebody shining there. It’s more like meeting someone for the first time, a kind of dance. So yes, a bit of boxing, but more inviting, with a bit of persuasion.

Jane: Do you see what you want to do pretty much straight away?

Emily: There is a capacity that we have as humans called ‘pareidolia’, where we see things that aren’t actually there. Particularly faces. It’s a useful ability to have if you’re lost in the woods, on the lookout for predators, and you can see two eyes in the bushes. If it turns out that what you were looking at are berries on a tree, you have been alarmed for no reason. Nevertheless, if it was a tiger, you would have been forewarned to get away fast. So people who didn’t have pareidoliac capacities were probably much easier prey.

So, we are perhaps all descendants of people whose pareidolia capacities were pretty good and so we have a tendency to interpret shapes and patterns as things that aren’t actually there, throwing a possibility into a visual act. My eye just does this all the time. I look at a stone and it seems that there are faces there already, created incidentally by nature’s processes. And a conversation is initiated. ‘Oh, I think that could be your nose. Let’s try it.’ So I tap and grind and chip and polish, and see what comes out.

With the quartzite stones, quite often they turn out to be tough guys. I call them ‘warrior poets’ because these are stone versions of our ancestors who fought, but they also had to be able to tell a good story of the deaths of kings. They have a quality of invincibility. You’d like them on your side.

Jane: You’ve done a great many of these faces over the years. Can you say a bit more about them?

Emily: Well, behind these pieces is the idea that after great battles, people used to sit on the ground and tell sad stories of the deaths of kings. These warrior poets wept for their dead – their dead brothers and sisters in arms. And for their children, as the deaths of children are often the hardest thing to bear. What did that look like? It’s a romantic take on something ancient and full of pain.

Stone can embody strong emotions. I think there are great sorrows that come simply with the territory of being human and in our present society we don’t have very many ways of honouring, in a poetic sense, death and pain and suffering. We may put up a statue of someone which represents the person in a literal sense, but often that does not reach more deeply than surface features. What I do is aim to make a carving of a head that anyone can look at and see, somewhere in there, their own story – see themselves in it, even if only for a split second. It is what literature, song, and theatre can also do, but those are in essence transient. These stones will endure.

All the warrior poets have closed eyes because these pieces are not only about our relationship with the world; they are also about our relationship with how we’re feeling. In stone, all emotion is gone. They’re not happy and they’re not sad; they’re not in pain and they’re not not in pain. They’re just being. And so, in all of the pieces, what I’m aiming for is a kind of Zen Buddhist state, a state of quietness, embracing all. Stone is so quiet. It holds it all.

It’s the same with the angels, the messengers from the gods – gods in the plural, not the singular. What does it look like when a human is at one with the universe? Embracing it all…

Archangel Michael (2004) carved from onyx. Installed in the grounds of St Pancras New Church [/] Euston Road, London. The plaque inscription reads: ‘In memory of the victims of the 7th July 2005 bombings [/] and all victims of violence. “I will lift up my eyes unto the hills” (Psalm 121)’. Photograph: Wikimedia Commons

Being Touched by Beauty

.

Phoebe: It seems to me that what you are doing with your sculpture is being a kind of interface – taking the material of the earth into people’s consciousnesses so that it can actually work on them.

Emily: I think that a lot of people in contemporary culture are not introduced to a level of beauty in a way that possibly people used to be. In the past, there was not so much busyness, and you’d have to walk quite a long way to get from your home in the steppes, or the forests or the deserts, to anywhere else. And as you walked, you would be in tune with things that had grandeur, like the night sky. People who live in cities now don’t often see the night sky – that great glorious roaring thing that can come at you every night. Given a clear sky of course…

I always remember at one of my early exhibitions – in St Pancras Church in Euston – a rather quiet woman who lived in a block of council flats nearby came into the crypt. She said: ‘I’ve never been to anything like this before. I had no idea that they did art shows in the church.’ She walked round, and when she came back she was crying and said: ‘I didn’t know I could feel like this.’

And she thanked us. She’d been touched by the beauty of carved stone. And that’s what I want my stuff to do. I want a piece to be so beautiful and so strong and honest that it produces this response in people. It could be the face of an angel. Quiet – very accepting, very loving. Able to hold people’s grief and love … helping them express something perhaps otherwise very hard to express.

Jane: You say in one of your videos that beauty is not negotiable. Do you mean that beauty is a kind of foundational principle, a necessity which we cannot avoid?

Emily: Personally, I think so, and I think we all recognise it. I’m not talking about physical beauty. You can see beauty in the face of somebody whose heart and soul has been torn to pieces in war. It’s a kind of innate wisdom, a communication of suffering, of love, of attachment. The idea that we cannot win when we fight reality. Those who aim at controlling life on Earth or in themselves are the biggest, cruellest idiots.

I think it is important to say that beauty must accommodate emotion. Compassion, and connection, are important words for me. I want people to feel connected to this lump of stone: I want it to say: ‘You see the history of the universe in me, and see that you’re a part of it, too. It’s your history. We are all connected. We are the product of everything that has gone before on the planet, and the planet is the product of everything that has gone before in our solar system, and that in turn of everything that has gone before in the universe.’ A repeatable truth, for now anyway…

The Young Guardian (2021) carved from Carrera marble. Lying on the seabed of Talomone, Italy. Photograph: Joshua Van Praag

The Stone Guardians

.

Jane: You’ve talked about what things stones can do for us as human beings, but I know that you’re also very ecologically aware and concerned about what we can do for the earth. You see the earth as a sacred place and have said that we should regard it as a temple; our duty is to look after it.

Emily: I actually think that that’s basically all we should be doing – once we can maintain ourselves in a state where we’re OK as living creatures in a complex natural world. The planet is a sacred place, and we really should just be looking after her and keeping her clean. Loving her. It’s a matter of caring for her, tending to her, not trying to control everything and turn her into something else. The kind of technocratic, dominating systems which are presently controlling the situation across the globe is a profound abuse of the planet. I find it almost unbelievable.

Phoebe: The project that has struck me because of its aliveness and its communion with the planet, is the one you have called the Stone Guardians, where some of your pieces have been sunk in the ocean off the Mediterranean coast in Southern Tuscany. As I understand it, the idea is that placing these very large slabs of marble on the seabed stops what is called ‘bottom trawling’ where a net is dragged across the ocean floor and removes everything from it, destroying the natural ecosystem.

Emily: Yes, the project has lowered about 50 of these sculptures, carved by various artists, into the sea in the coastal waters at Talamone in Southern Tuscany. The point is that the sculptures catch in the bottom trawling nets, tearing them and making it impossible for the dredger trawlers to do so much damage. The pieces are carved from huge blocks of Carrara marble, a few tonnes to 16 or 18 tonnes in weight, as the bigger they are, the more difficult it is for the dredger trawlers to come in close to the shore.

The project was initiated some years ago by a local fisherman called Paolo Fanciulli, (Pescatore) who fought back against the illegal trawling, at some danger to himself. The seas around Talamone used to be a very rich biodiverse area, full of life, with the forests of Posidonia seagrass covering many square miles. But when the trawlers came secretly at night, they tore up and killed virtually everything along the shore. They destroyed the biosystems of a wide variety of different environments and all kinds of creatures and plants, including the places where the sea creatures laid their eggs. The sea floor became dead.

Paolo started by dropping down concrete blocks. This worked a bit, but they were too small. Then, as he tells it, he thought: this is Tuscany, where Michelangelo comes from. Why don’t we get the living artists to do something useful? So he spoke with the owner of the Michelangelo quarry at Carrara – where his David was carved – and as a result, truckloads of huge blocks of marble arrived for us to work on.

Phoebe: And has the project worked?

Emily: Yes, very beautifully. The seagrasses, the Posidonia fields and forests, are growing lush again and the creatures of the sea are back; there are dolphins, lobsters, octopus, varieties of fish, sea snakes. It’s a feast for the eyes. A wide variety of sea plants have covered the blocks, waving gently and protecting the nurseries where so many of the sea creatures reproduce. So the barren wastes are fruitful again.

For more on this project, see the video The Stone Guardians [/] (duration 14:38) on Emily Young’s website

The sculptures themselves are becoming invisible, just part of this underwater world. People now come to Talamone to see the underwater museum, as it’s now called, so basically, everything’s thriving in there now. But there is a truly vast amount still to do – up and down the coast here, but also across the whole Mediterranean and the globe.

Archangel (2005), carved from chalcedony and onyx. Photograph: Angelo Plantamura

Move computer mouse over image to enlarge

The Power of Stillness

.

Jane: I think this project in Talamone is a lovely example of what you were saying before. If things are beautiful, if you put effort into making them beautiful, then it’s not a zero-sum game. Somehow there is benefit all round.

Emily: Yes. But there are many ways of experiencing and expressing beauty. So many things are short-term. But the mountains of stone stay the same for a long, long time, changing slowly through time, breathing very long breaths. And stone sculptures are perhaps like little mountains. Doing carving with beauty in mind is really an excellent way of spending the day. People pick up on it really quickly, if they have the chance.

Jane: The stones may be about change when we think of them in the long-term, but in comparison with our own nature and volatility, they represent stability and a kind of stillness. You have talked about the state of stillness that you yourself experience while you are working and said something that I like very much: that good things come out of stillness.

Emily: Yes. I think everybody has the possibility to experience this stillness – a capacity to go to that place in themselves. There are, of course, states of deep meditation which can be very profound and strong. But there can also be a sense of stillness when we are having a cup of tea, hurly-burly all around, and we are feeling something of the available quietness in the world.

And this sense of the stillness, the look of loving stillness, goes into the future. The human race probably won’t last forever. There might be people, descendants of ours, who find the residues of our cultures, going over the hundreds of thousands of years, and still, these stones might endure. I feel that the past spoke to me, and I heard it and felt it in the present. Now I send it off into the future. With my helpful companion and teacher, the stone.

I say all this, but actually, when I am working, I’m not really that self-conscious about what I am doing. I tend to let the task drive me and go where the wind blows. It’s essentially a responsive process. And a profoundly wonderful place to live in for those hours.

Phoebe: Emily, thank you so much for talking to us. There is so much more that could be said, but you have given us a wonderful glimpse of the secrets that stone can reveal to us.

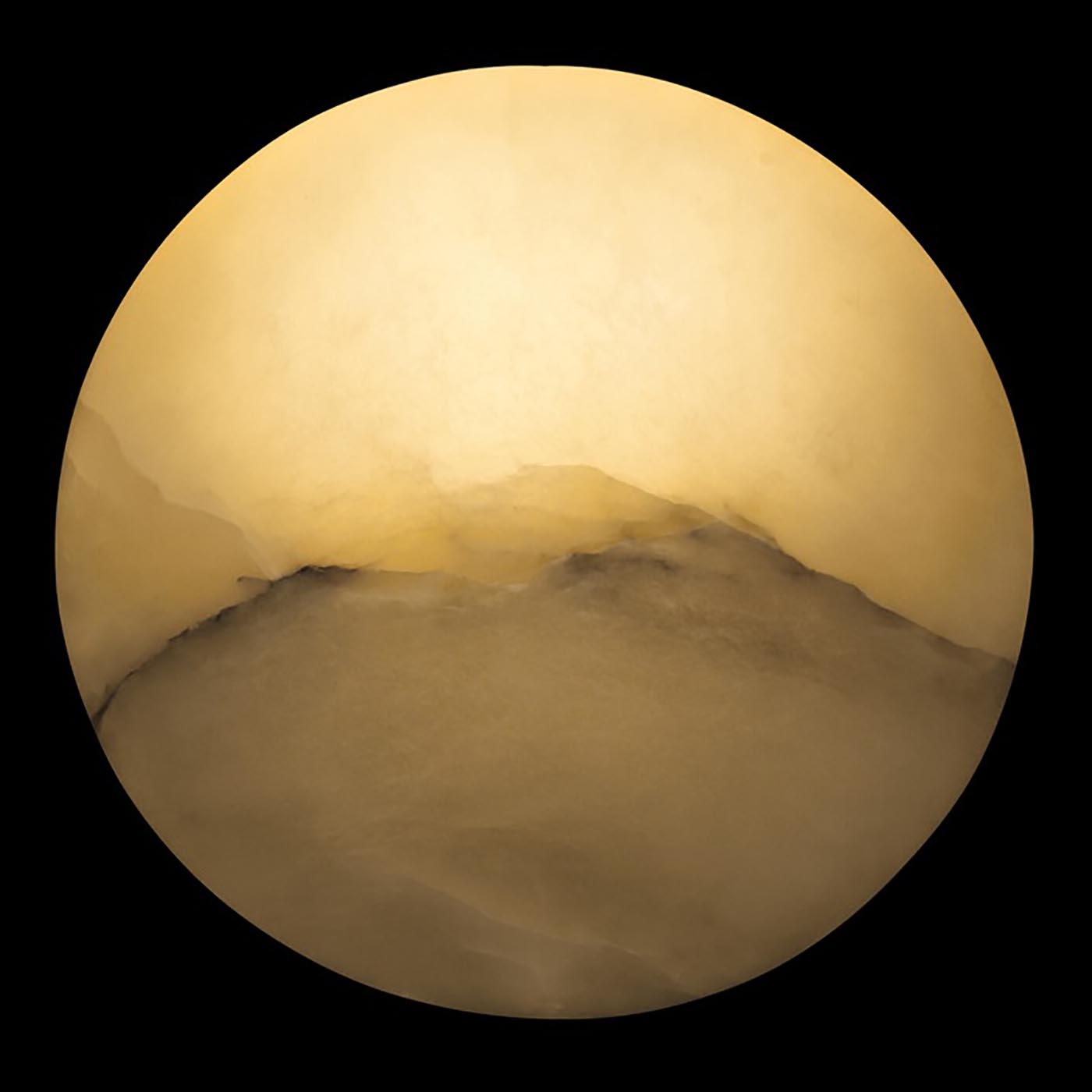

In this article we have focussed on Emily’s heads, but she has also worked on other subjects, including a series of large polished, translucent discs made by taking a section through a block of stone. She has said: ‘Whenever you take a slice through a stone, it looks like a planet.’ This one, 52cm in diameter, is entitled Alabaster Moon (2004). Photograph: Angelo Plantamura

Move computer mouse over image to enlarge

To see more of Emily’s work, visit her website emilyyoung.com

There is also a very informative new book by the eminent art historian Jon Wood, which was published this year: Emily Young: Stone Carvings and Paintings (Lund Humphries, 2024).

Image Sources (click to open)

Banner: Wounded Angel (2003), carved from marble. Installed in Kew Gardens, London, Photograph: Wikimedia Commons.

Inset: Emily Young.

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

READERS’ COMMENTS

0 Comments