Arts & Literature _|_ Issue 20, 2021

Exploring the Power of Love in ‘Attar’s Conference of the Birds

Kenneth Avery explores the famous story of Shaykh San‘an and its message of love and friendship across religious boundaries

Exploring the Power of Love in ‘Attar’s Conference of the Birds

Kenneth Avery explores the famous story of Shaykh San‘an and what it says about the crossing of religious and cultural boundaries

Farid al-din ‘Attar’s epic poem The Conference of the Birds is one of the spiritual masterpieces of the world. An extended allegory for the spiritual path, it has continued to inspire seekers, artists and commentators from the 13th century to the present day. In this article, Dr Ken Avery explores the meaning of one of the most famous sub-sections, ‘The Story of Shaykh San‘an and the Christian Maiden’ which relates the tale of a pious shaykh who falls in love with a beautiful young girl and abandons everything to follow his passion. He suggests that this radical and complex tale has much to teach us, in our divided world, about tolerance, empathy, friendship and love.

‘Let us love one another; for love is of God, and one who loves is born of God and knows God; one who does not love does not know God; for God is love.’ (I John 4:7–8)

‘I am one colour with your friendship, a companion of your love.’ (Jalaluddin Rumi)

As I write this, it is the twentieth anniversary of those terrible events of 11 September 2001 when the twin towers in New York were brought down. The media is awash with stories of horror and survival, of love and hate, of terror and forgiveness. It has also been recently filled with images and stories of the failure of Western nations in Afghanistan after twenty years of military intervention, and the great suffering of the Afghan people.

As I write this, it is the twentieth anniversary of those terrible events of 11 September 2001 when the twin towers in New York were brought down. The media is awash with stories of horror and survival, of love and hate, of terror and forgiveness. It has also been recently filled with images and stories of the failure of Western nations in Afghanistan after twenty years of military intervention, and the great suffering of the Afghan people.

There are, of course, some who would argue that this is a religious conflict, and that reconciliation between ‘Christian’ and ‘Muslim’ ways of thinking and acting is not possible. That this is wrong on so many levels is borne out by a deeper understanding of the historical, political, cultural and economic conditions operating over the many centuries of encounter between Western and Muslim-majority societies. Without addressing political and economic arguments, on a purely religious level there are many more common sources of inspiration and shared culture of the two faith-systems than differences – though admittedly this is not always evident. Islam is sometimes portrayed in Western eyes as monolithic, intolerant, backward looking and hostile to the Christian values which used to underpin Western societies. But an understanding of mainstream Islamic culture and literature makes this view untenable.

In this short article, I wish to focus on a writer from the classical age of Persian literature – from the period which Westerners call medieval – as an illustration of what can be learned of tolerance, empathy, friendship and indeed love across religious boundaries.

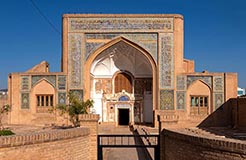

Farid al-din ‘Attar (d.1220) lived in the late 12th, early 13th centuries in what is today north-eastern Iran, working as a pharmacist/physician in the bustling city of Nishapur, a great centre of culture and learning. He wrote several books in rhymed couplet form, a collection of lyric poems and a prose hagiography, all showing his great erudition and understanding of the Sufi path of love and spiritual journeying. His works invite us into the transcendent world of Sufi spirituality, but he is also a superb literary craftsman and an inspired story teller, his writings couched in a mellifluous poetic style.

His story-telling skills come to the fore in his most well known book, written in rhyming couplets, Mantiq al-tayr, usually referred to in English as The Conference of the Birds.[1] This masterpiece contains a primary framework narrative interspersed with secondary stories and anecdotes culled from religious and secular history, folklore and everyday life. The ‘theme and illustration’ genre has a clear didactic purpose for aspirants on the Sufi path, but it is also aimed at non-lettered listeners as well as more literate readers.

The frame story in the Conference is an allegory about a group of birds, led by the wise hoopoe, who undertake a journey in search of their king, the legendary simurgh. At first, each bird makes excuses for its timidity in this venture, but the hoopoe, a thinly disguised Sufi master, gives encouragement and advice for the quest. After many trials and guidance through seven allegorical valleys, thirty birds (si murgh) reach their goal of self-discovery. They finally realise that they themselves contain the truth they have been seeking: with their selves purified by their quest, they become one with the Truth. ‘Attar here tries to speak of an encounter which cannot be put into words but is experienced as divine grace.

Move the computer mouse over the image to enlarge

The Story of Shaykh San‘an

.

The focus of my purpose here, however, is not on ‘Attar’s esoteric – or indeed ineffable – teachings but rather on a beautifully expressed story about the transformative power of love in all its aspects, across religious and cultural horizons.

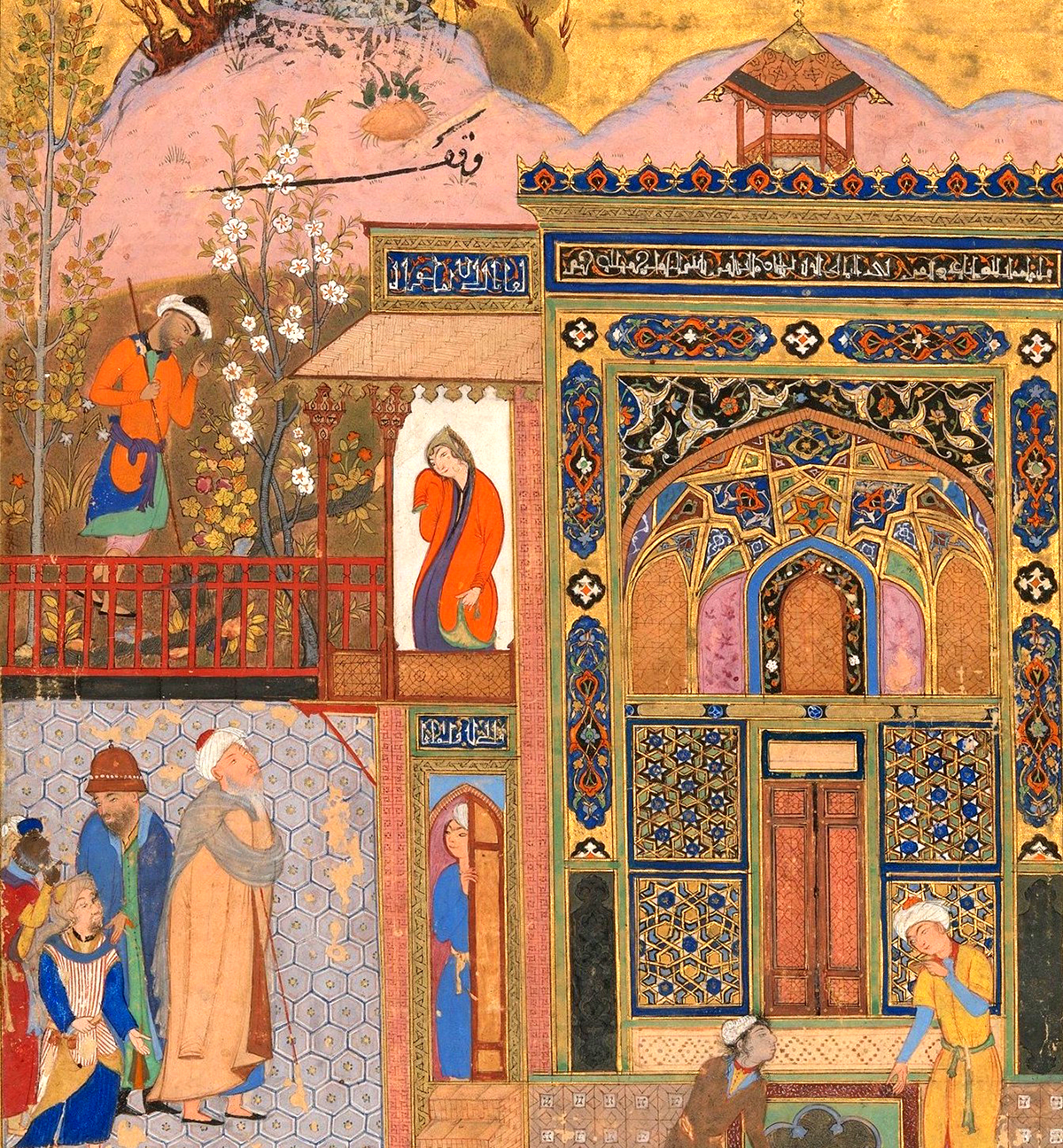

The story of ‘Shaykh San‘an and the Christian Girl’ is the longest and arguably the most important fable contained in the Conference of the Birds. It is a complex, baffling, and even iconoclastic tale of love, desire, betrayal, friendship, empathy and compassion. It is played out between an aging, revered, pious shaykh from Mecca – the heartland of Islam – and a young, dazzlingly beautiful, woman, a Christian devotee from Byzantine Turkey. The story begins when the pious shaykh, secure and surrounded by many followers in Mecca, has disturbing dreams of worshipping an idol in Rūm (the eastern Christian Roman empire or Byzantium). He is determined to find the meaning of the dream and sets off to visit Rūm; as soon as he arrives, he falls hopelessly in love with a young Christian woman of exceptional beauty.

He camps at her door for a month, stricken and distraught until she eventually begins to taunt him. He declares his love for her but she demands that he abandon his Muslim faith, burn the Qur’an, worship idols and drink wine, all abhorrent to his faith. The shaykh accepts all of these demands but she then insists that he become her swineherd for a year, in utter degradation. In despair, his followers limp back to Mecca where his chief disciple who had not accompanied them to Rūm castigates them for abandoning the master.

They all return, and in their fervent prayers a vision of the Prophet Muhammad assures them that the shaykh is freed of his infatuation. They find him repentant and remorseful and all return to Mecca. Meanwhile the young woman has a dream telling her to adopt the shaykh’s faith; she awakens realising her folly and runs after the master, imploring forgiveness. He admits her to his path but her pain is too much and she soon dies of grief and shame.

In this bare outline the tale is a ‘fall and redemption’ fable with the ‘hero’ undergoing numerous trials before he emerges triumphant with the vanquishing of his opponent. But this is a superficial reading of a story which holds great subtlety and complexity, written by an author who is not afraid to subvert conventional narratives of faith and unbelief, or symbols of piety and apostasy. Before exploring these themes, however, some context to this story needs to be given.

Firstly, the Shaykh San’an episode occurs about a quarter of the way through the book where all the birds are wavering with indecision about undertaking their perilous journey. The hoopoe tells the story in an attempt to win them over and give them courage for their venture. In this s/he succeeds admirably: the story of the loss of self at this crucial point in the book convinces the other birds of their need to forge ahead on their flight of discovery.

Secondly, in dealing with interfaith issues, it is important to remember that the ‘Christianity’ ‘Attar portrays in the Conference of the Birds is not what we understand today in the West as Christianity. For Muslims of ‘Attar’s time there was little differentiation made between Christians, Jews or Zoroastrians; all were minority religions living under Muslim polity, known from the Qur’an as ‘People of the Book’, i.e. faith communities possessing earlier written scriptures. There was generally a good deal of tolerance for these minority faiths but there were civil and economic restrictions, such as wearing distinctive clothing, taxation disadvantages and sometimes being treated as second-class citizens.

In the story of Shaykh San’an, the ‘Christian’ faith he is enticed into involves renouncing Islam, burning the Qur’an, worshipping idols and drinking wine. He is also made to enter a ‘monastery’ where there are idols and wine drinkers, but it is a Magian (Zoroastrian) monastery (dayr mughān), a poetic figure common to Persian lyrical poets. This is not the only occasion in the story where ‘Attar refers to Zoroastrian rather than specifically Christian symbols and nomenclature. This confusion of referents is perhaps poetic licence, but it is also a warning against an overly literal reading of the text. It makes it difficult to link these Christian symbols with the denomination of the Church of the East (known pejoratively in the West as Nestorians), prominent in Iran and along the silk roads during the Middle Ages. Their iconography and use of wine in the eucharist could account for these references, but ‘Attar is a poet rather than an historian.

Given these caveats, we can now go on to look a little closer at this remarkable story and its implication for spiritual journeying today.

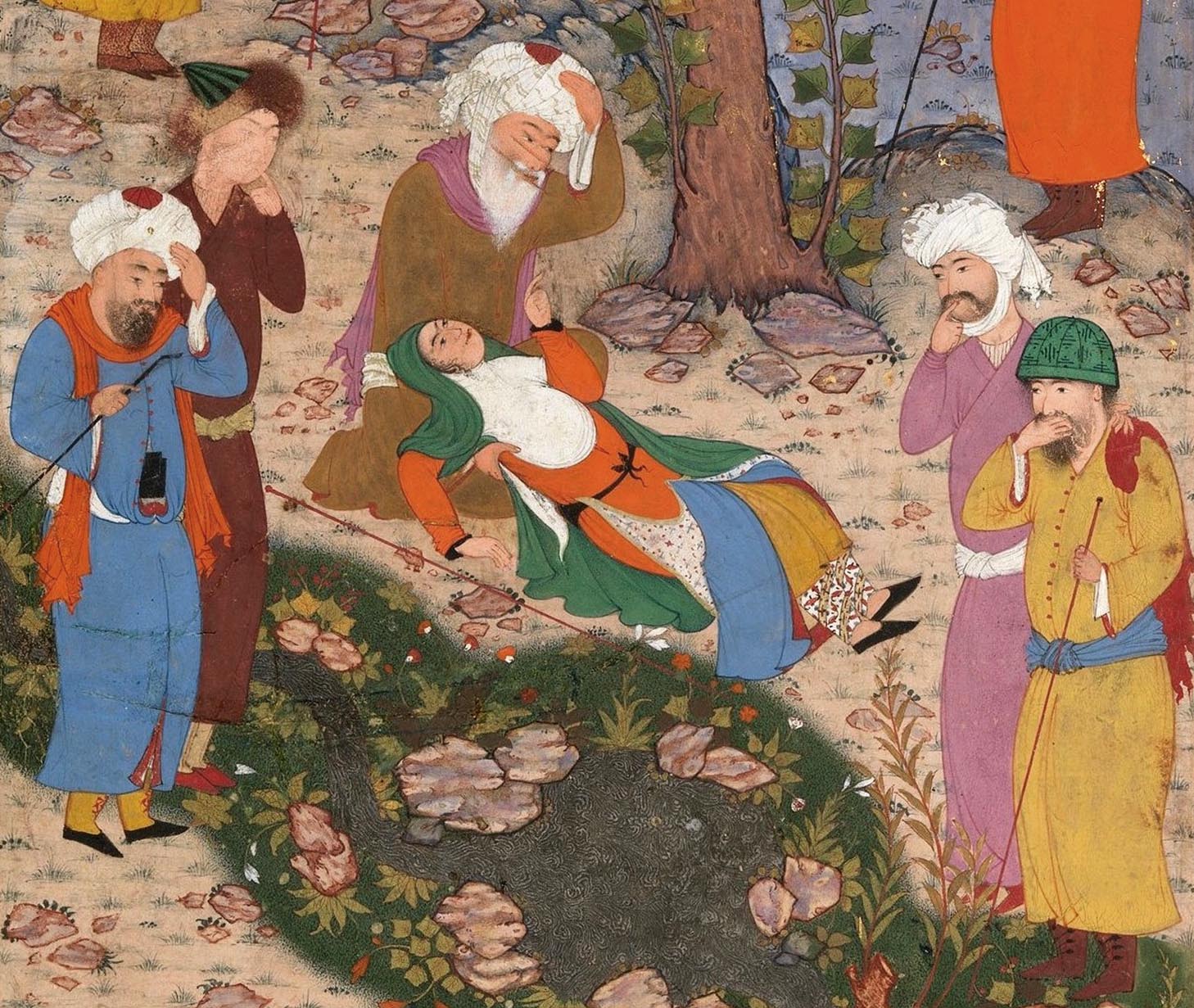

Shaykh San‘an beneath the balcony of the Christian maiden. Detail from Folio 18r of the royal manuscript of Conference of the Birds, 1487, Isfahan, Iran; illustration an addition by an unknown painter, c. 1600. Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Move the computer mouse over the image to enlarge

Falling in Love

.

At the beginning of the tale the shaykh is portrayed as a faithful and highly respected leader of his community, with 400 followers – the pinnacle of piety and conventional religious faith and practice in the holy city of Mecca. But as soon as he began to have disturbing dreams of worshipping an idol in Rūm, he knew what this entailed. He immediately sensed that all his piety was of no value if these dreams continued:

I do not know whether I can live with this grief:

I have said that I have to die if I lose my faith.[1]

This mention of having to die (tark-i jān) means in this context abandoning the full sense of self and being to which the shaykh was accustomed in his conventional, religiously-contained and prescribed life.

The shaykh is determined to find the source of his recurring dream and hastens to the ‘Christian’ land with his 400 followers in tow. ‘Attar leavens the seriousness of this undertaking with allusive and piquant humour:

They travelled from the Ka‘ba to the extremity of Rūm;

they went round and round every part of Rūm.

The ‘extremity’ (aqṣā) alludes to Jerusalem while ‘round and round’ (ṭawf) alludes to the circumambulation of the Ka‘ba during pilgrimage

When the shaykh discovers the young woman, her great beauty is described in typically exaggerated language familiar from the Persian poetic tradition. Images of light, fire, sun, stars, and so on, abound:

In the sphere of beauty and the constellation of gracefulness

she was a sun, but one that did not set.

Yet her physical beauty is mirrored by spiritual beauty as well. She is portrayed not as a brazen siren intent on luring the old man to destruction – at least not yet. She is initially described as:

That young Christian woman of spiritual qualities (rūḥānī ṣifat)

with a hundred intimations of divine knowledge on the path of the spirit of God.

The shaykh immediately falls desperately in love with the hopeless infatuation of an old man for a beautiful young woman. The love is openly erotic, passionate and painful, described in terms of fire and darkness. He cries:

Like a candle I am extinguished by heat and burning;

burning continually at night and snuffed out by day.

‘Attar comments:

All which was his, before his eyes, was no more;

his heart was filled with smoke from his passionate melancholy.

His companions try to reason with him and counsel repentance, but the old man realises he has lost his position of authority, his social standing and all that was part of his former life:

I have repented of fame, honour and high standing,

free of being a revered elder, of speaking and teaching.

Distraught and on fire he camps at the woman’s door, seeking seclusion (khalwat – a word usually meant for spiritual retreat and secluded prayer) with the stray dogs of her street. He professes unconditional love for her:

I will lose my life (jān) for you if you give the word […]

I am going to the grave with a burned soul (jān),

the world ablaze from the fire of my being (jān).

This word jān is worth a bit of exploration. It is a multivalent Persian word which I have highlighted in the translation excerpts to show the fluidity of its meaning; traditionally translated as ‘soul’, it means much more – such as ‘life’, ‘being’, ‘true self’, etc. – depending on context. Its Sanskrit cognate dhyāna travelled by way of Buddhism to reach Japan, to be rendered as ‘Zen’.

Shaykh San‘an drinks wine at the bidding of the Christian maiden. Oil painting, late 19th century, Iran. Image: Jonathan ORourke/Alamy Stock Photo

Drinking the Wine of Love

.

Following the shaykh’s declaration, the girl begins to taunt him about the hopelessness of his love and the physical and spiritual disparity between them. Finally she demands four things before he can become her lover: bow down to an idol; burn the Qur’an; drink wine, and turn away from his faith. At first the shaykh is willing to drink wine but does not agree to the others. This is significant since the wine he drinks is the experience of erotic/mystical ecstasy:

She said: ‘Arise! Come and drink wine;

when you have drunk you will shout out!’

They carried the old man to a Magian monastery,

his companions following clamorously.

The shaykh of the Truth (al-ḥaqq) glimpsed a new crowd,

he saw the party’s host was immeasurably beautiful;

The fire of love carried off his dignity;

the tresses of the Christian carried off his life.

Not an atom of his reason or understanding remained;

without a word he drank up;

He took the cup from his friend’s hand;

he drank and his heart was broken.

The wine of erotic ecstasy removes all knowledge and memory of his former life and learned ways. He is enraptured and in this state he succumbs to her other demands:

Love does not agree with a comfortable life:

a lover must always be an unbeliever.

If you venture resolutely in love

Your path (madhhab) is these curled tresses.

Her invitation for him to ‘convert’ is more allusive than literal; she entices him into a religion of love, eroticism and ecstatic experience occasioned by wine and the lure of youthful beauty. He agrees to burn his books in front of an idol, but ‘Attar is ambiguous about the nature of the idol, whether it is a religious icon or the young woman herself who is described thus poetically. She tells the old man:

Before this time you were raw, raw in love;

live well, for you are now cooked, so there! […]

Well-cooked intellect (‘aql) is merely learning the alphabet of love;

love knows what is hidden (ghayb) and what bewilders.

The shaykh seeks her hand in the union of marriage but she rejects him because of his age and poverty. He feels betrayed and grieved: having thrown away everything for her love, he responds with the vehemence of unrequited passion, in language reminiscent of ‘Attar’s lyric poetry. Then comes the punch: she demands he become her swineherd for a year; his degradation is complete. ‘Attar comments:

When you begin the path, O man of action,

you will see both idols and pigs a thousand fold;

Kill the pigs; burn the idols in the desert of love,

else become like the shaykh, disgraced in love.

At this point, the shaykh dismisses all his followers, who return distraught to Mecca. One of his followers, however, had remained in Mecca the whole time and had not travelled to Rūm. When he hears the sad story he castigates the others for not staying and supporting their master:

When he bound on the Christian girdle (zunnār)

you should all have done the same!

You should not have left his side voluntarily:

you should all have become Christians!

He goes on to say that true friendship persists even though the friend becomes an unbeliever:

When the shaykh fell into the mouth of a crocodile

you all fled from him, fearing for your reputation and honour.

Love has its foundation in disrepute (bad nāmī);

all who turn away hypocritically are unripe (khāmī).

With these words about the nature of friendship, this tale suddenly reaches its pivot point which will eventually lead to its resolution. The shaykh’s faithful disciple urges prayer and supplication, and this is performed so vociferously that heaven is aroused. The Prophet Muhammad appears in a dawn vision telling all the followers that by their prayers and fasting the shaykh has been freed from his bonds and his sins forgiven. The followers hasten back to find him remorseful and repentant, with all his wisdom, learning and memory returned. ‘Attar makes clear that it is through the Prophet’s intervention that the shaykh is forgiven and his actual repentance is not much emphasised.

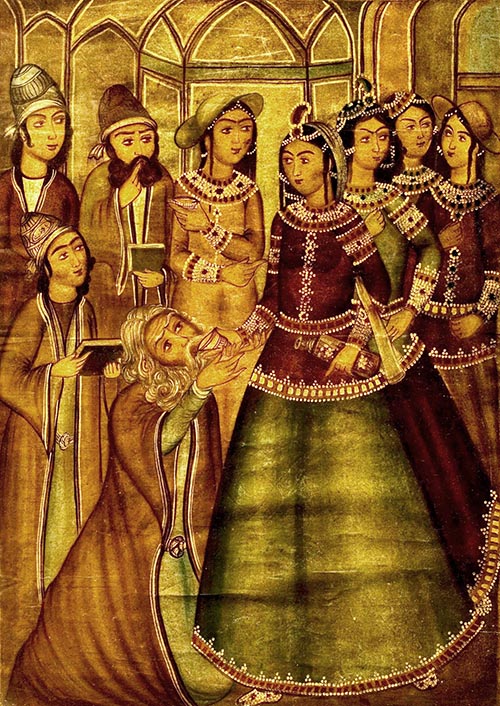

The Christian Lady submits to Shaykh San‘an. Detail from Folio 22v of the royal manuscript of Conference of the Birds, 1487, Isfahan, Iran; illustration by an unknown painter, c.1600. Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Move computer mouse over image to enlarge

The Transformations of Love

.

The attention of the story now turns to the fate of the young woman. She has a dream in which she is told to adopt the shaykh’s path (madhhab); on awakening she realises her folly and runs after him, imploring forgiveness in anguished prayer:

For all which I have done, do not take offence; I am miserable:

I have accepted your faith; do not regard me as irreligious (bī-dīn).

The shaykh is told by an inner voice that the woman has repented:

She has found friendship in Our (i.e. God’s) court:

her situation has found remedy now on Our path.

Turn around and be with that idol again:

become a friend and confidant of your idol!

This, it seems to me, is the crux of the whole story. There is great gentleness and sensitivity in ‘Attar’s description of the woman’s conversion, and great compassion is enjoined on the shaykh. Despite the harshness of her earlier demands on the old man to convert her to ‘Christianity’, now that he has been humiliated and purified of his conventional, narrow religiosity, he is called to become a friend and confidant of the ‘idol’ – the formerly disdainful beauty who led him ‘astray’ into his enlightenment.

She now implores the shaykh to teach her the path of submission and the way of Truth (rāh-i ḥaqq). He obliges, but her remorse and sorrow weigh so heavily on her that she bids farewell to the world:

That moon-like one said this and left her life (jān);

she had half a life (jān) and scattered it over her Beloved Lord (jānān):

Her sun became hidden behind a cloud;

sweet life (jān) separated from her, alas!

‘Attar mourns her death, and thus the story ends with these closing lines:

Like the wind we all pass from the world;

we all depart like her, all of us.

Many times [this story] has happened on the path of love;

one acquainted with love will know this […]

The carnal self cannot hear the secrets [of love];

it is said that someone without a fortune cannot be robbed.

This [secret] must be heard by the ear of our inmost being (jān) and heart,

not by the painted form of water and clay [our physical body].

The war between the heart and the carnal soul intensifies every moment:

cry out in lamentation as the mourning increases.

On this path our watchfulness must be great

if we are to dive into this deep sea.

Of course ‘Attar had to end this subversive story in a conventional way with the woman converting and the shaykh returning to his traditional path. Otherwise the Conference of the Birds would have been banned and the author arraigned before religious or civil authorities in 12th-century Nishapur. But ‘Attar had already subverted the established protocols, both in this story and in other places throughout his writings, despite the apparent formal pieties of his Sufi themes and subjects.

Both the shaykh and the woman are transformed by true love. From the security, conventionality and complacency of the shaykh’s religious and social standing he is utterly devastated by erotic and mystical ecstasy, and eventually returns to his former self enlightened by love and friendship for his new disciple, the young Christian woman. She, on the other hand, is transformed from her ‘religion’ of haughty self-regard, of narcissistic beauty, of contempt and cruelty for lesser mortals, until she learns too late the path of humility and true self-worth.

In this story there is love in all its forms: divine, erotic, passionate, compassionate, as well as friendship, forgiveness, and the pain of unrequited love. But what is important today is the view – uncommon if not radical for ‘Attar’s time – that friendship and love cut across religious or denominational horizons and connect believers and unbelievers alike. Conventional religious behaviour and personal piety are not enough: they may even lead down the wrong path. The freeing of religious faith in the loss of self and self-regard is the only way to show love in the world, and to attain true spirituality.

‘Attar’s tomb in Nishapur, which continues to be much-visited in the present day. Photograph: Ebrahim Rahiminezhad [/] via Wikimedia Commons

Kenneth Avery is an Australian, a teacher of music and a writer. He studied Semitic and Islamic studies at the Universities of Sydney and Melbourne, and has published books on early Sufism as well as Fifty Poems of ‘Aṭṭār, an edition and translation of selections from ‘Attar’s lyric poetry (with Ali Alizadeh)

Image Sources (click to close)

Banner: ʿAttar and his fellow poet Navaʾi reflect upon the meaning of the story of Shaykh San‘an on either side of the Tree of Life. Detail from Folio 22v of the royal manuscript of Conference of the Birds, 1487, Isfahan, Iran; illustration by an unknown painter, c.1600. Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Inset: King Solomon’s Hoopoe, spelling out the ‘bismillah’ – the phrase meaning ‘in the name of God’ which begins every surat of the Qur’an. The hoopoe is associated with love because it carried the letter from Solomon to Bilqis, the Queen of Sheba, inviting her to visit his court. Image: AKG-images.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] There are several full translations of this text into English. The most accessible is probably: AFKHAM DARBANDI and DICK DAVIES, The Conference of the Birds (Penguin, Second Edition, 2011).

[2] All translations are by the author, based upon the printed edition of the text: Fariḍ al-dīn ‘Attār, Manṭiq al-Ṭayr, ed. M.J. Mashkur (Kitab-furushi, Tehran, 1353 a.h.s).

[3] Works by KENNETH AVERY:

- A Psychology of Early Sufi Samā’: Listening and Altered States (Routledge, 2004).

- Fifty Poems of ‘Attar (with Ali Alizadeh) (re-press, 2007).

- Shibli: His Life and Thought in the Sufi Tradition (SUNY, 2014).

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

The Heritage of Afghanistan

Robert Darr reflects on his long relationship with the people and culture of this ancient land, and shares his insights into its present situation

The Zoroastrian Flame

Khojeste Mistree talks about one of the world’s oldest surviving religions and what we can learn from it in the present day

Rumi: The Operation of Divine Love

Alan Williams tells us about his new translation of Rumi’s great epic poem, the Masnavi

Towards a Deeper Spirituality

The Reverend Peter Dewey looks back on a lifetime working with interfaith projects

READERS’ COMMENTS

Sublime – thank you all. Edward FitzGerald translated,pruned and adapted this work just before the Light triggering work Ruba’iya’t of Hakim Umar Khayya’m was given to the world… Genius Awakens Genius .

Thank you- I’m halfway through reading conference of birds and this story is one of my favourite parts so far, it felt very unexpected and I loved the don’t give up on your friends (if one of you goes down, you go down to hell together vibe).. sorry not really an educated reader, just reading out of interest but was wondering if you could explain a bit on the story of shebli- I’m trying to understand whether Attar is pro shebli being kind of gender fluid and having complicated sexual desires/ and not pretending to be something he’s not? Or is he saying that shebli is pretending to be a Sufi but hiding idols in his cloak? I feel like the general gist is stay humble and don’t pretend to be something you’re not, but think I’m a bit confused about Attar’s take on Shebli.. would really appreciate how you understand this passage. Thanks!