Arts & Literature _|_ Issue 13, 2019

A Celebration of Nature

Artist and gardener Laura Blackwood talks to Elizabeth Roberts and Kawther Luay about the importance of connecting with the natural world

A Celebration of Nature

Artist and gardener Laura Blackwood talks to Elizabeth Roberts and Kawther Luay about the importance of connecting with the natural world

Laura Blackwood is an artist and painter who creates intricate, meticulously observed works of art celebrating the natural world. She studied originally at the Canterbury School of Art and the Beshara School, then, in the 1980s she and her husband Simon moved to the Scottish Borders, where Laura embarked upon a forty-year project to establish a garden in the grounds of their cottage. She has produced several illustrated series, including a limited edition book, A Celebration of Nature, which tracks the year through the seasons. We visited her at her home to ask about her latest work, The Kitchen Calendar, which she has just completed after five years of work. At the end of the article, you will find a ‘walk-through’ of this which has been created specially for the Magazine.

We met Laura in mid-summer and talked in her studio at the back of the house, overlooking her garden, which leads, in a series of terraces, past the vegetable patch down to the river, Rule Water. Beyond its banks, we can see the lovely landscape of the Borders stretching to the horizon. What is it about nature, we ask, that so inspires her? “I think that what inspires anyone to paint or garden or do anything of that nature is because it is full of meaning”, she replies. “Gardening is a huge uphill struggle, as anyone will tell you – battles with every kind of pest and weed – but the end result is such a joy and pleasure, especially if you can share it and people come to enjoy the fruits of your labours.”

We met Laura in mid-summer and talked in her studio at the back of the house, overlooking her garden, which leads, in a series of terraces, past the vegetable patch down to the river, Rule Water. Beyond its banks, we can see the lovely landscape of the Borders stretching to the horizon. What is it about nature, we ask, that so inspires her? “I think that what inspires anyone to paint or garden or do anything of that nature is because it is full of meaning”, she replies. “Gardening is a huge uphill struggle, as anyone will tell you – battles with every kind of pest and weed – but the end result is such a joy and pleasure, especially if you can share it and people come to enjoy the fruits of your labours.”

One of the fascinations for her is that the landscape is continually changing. “The wonderful thing about this garden, because it’s on a steep slope, is that there is a lot of variation in the light at different times of the day. If the sun is shining, in the morning it lights everything up from underneath; in the afternoons, it is lit from above.”

“And of course, we are lucky in this country to have very definite seasons. I find it very inspiring to see the cycle that starts mystically in spring and then blossoms and blooms into fruit and vegetables and flowers in the summer. Then in autumn, it is it all dying back, and then you get a period where everything is becoming dormant in preparation for the next season, or year. I find all this really amazing and wonderful to watch in both the plants and wildlife which inhabit the garden.”

Both of Laura’s major artworks – A Celebration of Nature [/] and her sequence of paintings in The Kitchen Calendar [/] – track this yearly transformation as it occurs in her immediate environment. Whereas many artists have been inspired by a change of location – we can think of Matisse and van Gogh in the South of France or Gauguin in Polynesia – the quality that emerges in Laura’s work is of close and careful observation from the same spot over a long period of time.

We ask: does the process of drawing and recording deepen her appreciation of the things she sees around her? “Absolutely. For one thing, you start to notice the uniqueness of each thing. A lot of snowdrops come up in the woods here each winter, and superficially, they all look the same. But when you look closely, you can see that each one is completely different. At the same time, they are all expressing what might be called an archetype. So there is a contemplation here about uniqueness which can also be applied to ourselves as human beings. There are billions of us on the planet and we are all similar forms of humanity; but equally, we are all individuals. How can this be?”

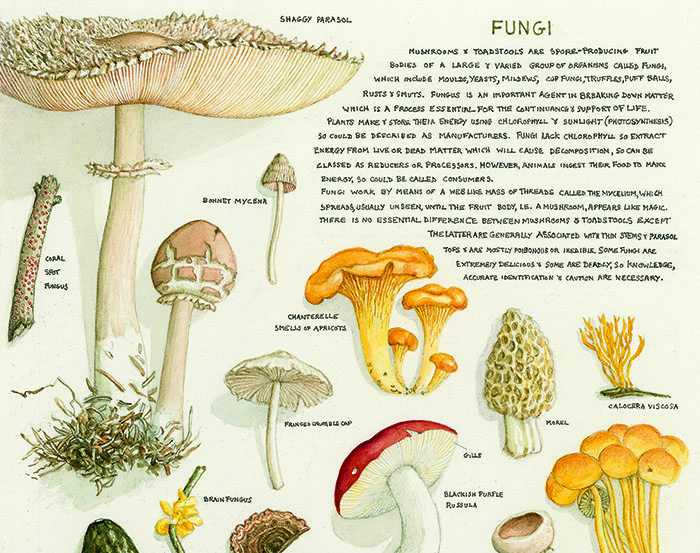

She goes on: “Once you begin to look into nature in all its variety, you realise that it is infinite. You can just take one subject – a snowdrop, a mushroom, a moth – in one place in one corner of the world, but when you start really looking at it, you get drawn in deeper and deeper and perceive just how intricate and beautiful these creations are.”

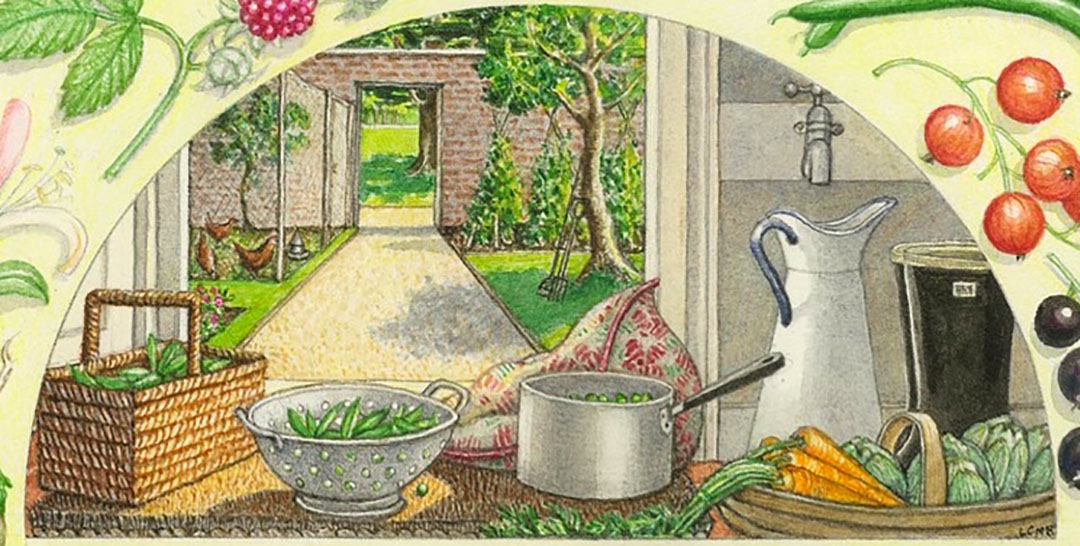

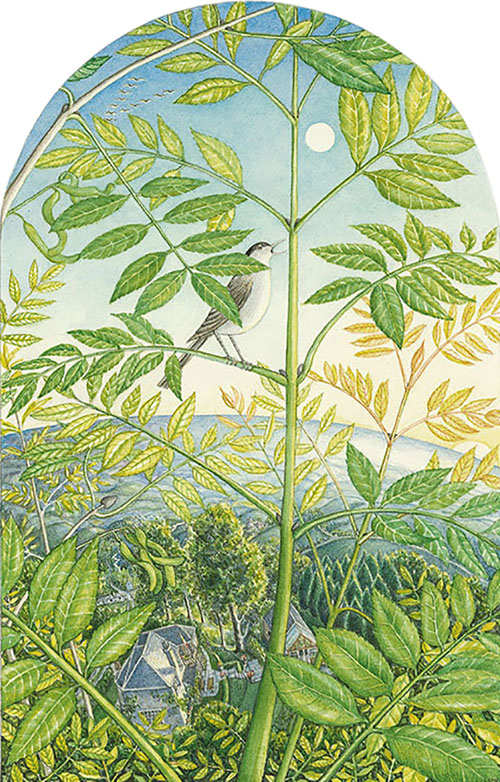

From A Celebration of Nature: September

Learning to See

.

This quality of attention is not so easily achieved: to see something for what it really is, uncoloured by our own state, takes application and practice. Laura agrees. “But when it happens, you become totally engrossed in that moment, doing that thing; when you sit and draw something, you are taking in whatever information is in front of you, it’s going through you and coming out of your hand on the paper. It is a complete action, like digesting food.”

She feels that close observation of the world is helpful for everyone, especially in the present day when, as a society, we find ourselves increasingly alienated from nature. “It is clear that humanity is facing an enormous challenge. How to live on this planet without destroying it? The rapidly increasing number of people; the decreasing number of species of insects, plants and animals on which we depend; pollution; indiscriminate use of chemicals and insecticides, etc.; poor farming practices and bad land management – there are many issues which seem beyond hope of a solution, and these can make one feel impotent to change anything. But I believe there is a very strong action that anyone can take, and the first step, and potentially a joyful one, is the simple action of learning to observe in a receptive way – to open one’s eyes and senses to nature. This can have a huge effect.”

She is a great believer in education as a means of bringing about change, and has put her ideas into practice with local children by setting up a Sunday art club. “What we wanted to do,” she explains, “was to get these children to just look, by being still, being quiet and really just being present.”

So how did the children react? “Well, it was amazing. We told them to go off and find a tree and sit and draw it or paint it, and they were completely into it. They didn’t go off in a gang and giggle, but they all sat dutifully drawing. And while they were doing that, they could hear all the birds singing and the river flowing; they could smell the grass and the plants that were all around them. All this begins to make a connection with nature, both inside and outside, which is absolutely vital. It doesn’t matter whether you’re going to be a fantastic artist – that’s not the point: the point is just learning to see.”

This is all very well, we point out, when you are in the idyllic setting of the Scottish countryside but not so easy when people are living in the midst of a city. But Laura maintains that these steps can be taken anywhere. “However small or vast the action, this is open to anyone, even in the middle of a concrete metropolis, whether you are rich or poor. I feel it would be a huge step in the right direction if every child planted, grew, cooked and ate and shared a crop, however small, and planted at least one tree. Anyone can find space to plant a window box and grow herbs. When you invest effort in something and reap the reward, that encourages you to appreciate its value and even to care for it. North American Indians believed you should not trash the land on which you depend because it is like your mother, who deserves love and respect. We have to understand that we depend totally on nature; we are part of it, not separate.”

Laura in her studio with the red squirrel at the window

Interconnectedness

.

For Laura, the sense of deep connection with nature is very much mediated by her relationship with her garden. “Although I have tamed bits of it – to grow vegetables for instance – it is essentially a wild garden. We have wonderful birds and wonderful plants, a lot of wild flowers, some of them quite rare. When I find them in places that might get trampled on, I move them to somewhere where they can flourish, so I see it as a bit of a sanctuary. I consider a lot of wild flowers to be my friends. I greet them as they appear throughout the year, and it’s such a pleasure.”

She has also formed relationships with some of the local wildlife; there was a blackbird called Molly, and a red squirrel which used to visit her in her studio. “For these kinds of encounters to happen, there has to be a certain receptivity, alertness or quietness to your approach. It’s a real thing to just be completely receptive. But perhaps there is even more than that; it’s like being in awe of something – you approach it with real respect and wonder. And then, things happen. When people come here wanting to see a red squirrel or a particular bird, will it appear? No. It’s when you’re being really quiet that it happens. With the red squirrel, I was sitting painting by the window every day, so I was very passive and absorbed in what I was doing. She became completely used to me to the extent that eventually she felt at home, and would come in and feed from my hand.”

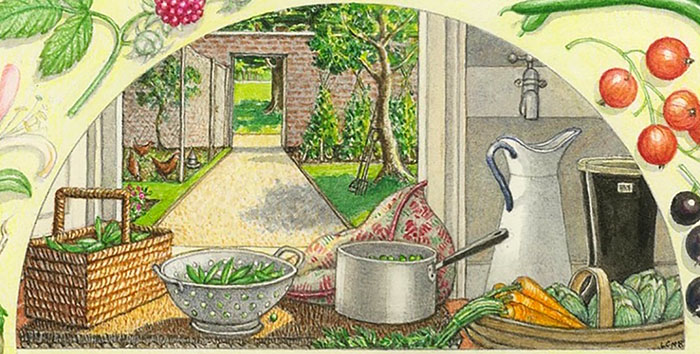

The garden from the vegetable patch

We want to know more about her remark that the garden is a kind of sanctuary. Does she see it also as a place of healing? “Yes. I’ve always thought of nature in the gardening sense as being incredibly generous and capable of healing. A disaster happens and it’ll overcome it. You don’t get ten seeds from a plant; you get a thousand. And as for healing; we all know that nature does this. There are now projects [/] that take children, particularly children with special needs, out into nature and the woods, encouraging them to be involved by getting them to look at things. This undoubtedly has a healing effect.”

In her book A Celebration of Nature, she mentions the figure of the ‘green man’ – in the Islamic tradition known as Khidr [/] – as being an important concept for her in both her gardening and her painting. “There are a lot of depictions of Khidr through the ages. In the western tradition, the story is that the seeds that were placed under the tongue of the dying Adam went on to produce the tree from which the cross of Christ’s crucifixion was made. This then becomes the foliate head of the green man, who is usually presented in cathedrals, or on tombstones.”

So how does she understand the meaning of this figure? “It is an extraordinary image of renewed life. He is the representation of the life force within every human being, in nature and in all of existence; a symbol of the direct conscious connection of one absolute being to all of creation without any intermediary. Khidr is the teacher for those with no teacher, so he is to do with learning essentially and directly from things. And this is what happens when we start to really look at what is in the natural world.”

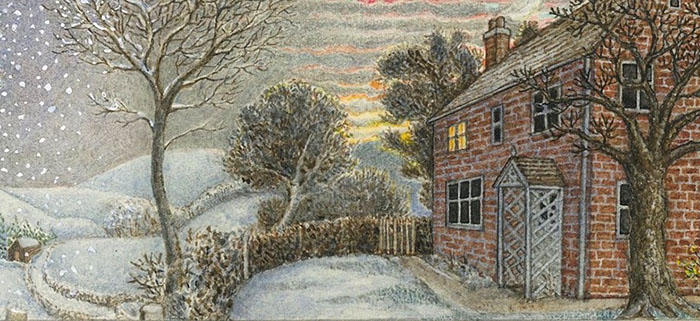

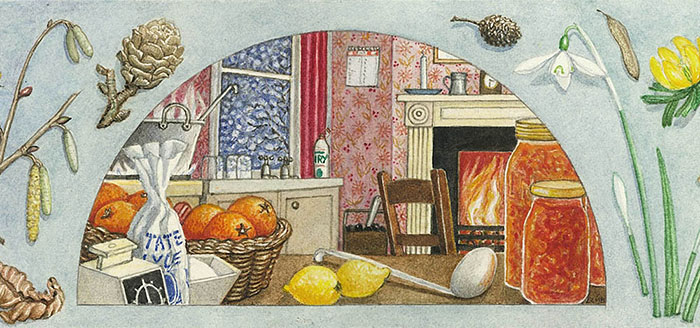

From The Kitchen Calendar: the landscape in January

The Still Point

.

This theme of renewal, of the rhythm and cycles of nature, is expressed in her art through the technique of setting a fixed point of vision and then creating a panoramic circular view around it. This is very beautifully shown in the ‘walk-through’ of the kitchen calendar which has been created for this article [see below], but it is also a feature of many of her other pieces. Where does this idea come from, we ask? “Well, one inspiration has certainly been the turning of the Mevlevi Dervishes – sometimes called the ‘whirling dervishes’ – and all the meanings associated with that.” Laura’s reference point here is the film Turning (see video right or below) made in the 1970s by Bulent Rauf and Diane Cilento, which begins with the famous lines by T.S. Eliot in The Four Quartets:

At the still point of the turning world. Neither flesh nor fleshless;

Neither from nor towards; at the still point, there the dance is…

Video: Turning by Bulent Rauf and Diane Cilento. 47:29 minutes

“The important thing about a panorama,” she explains, “is that it puts you, the viewer, at the centre of things; it is what you witness as you turn. A 360 degree view indicates complete consciousness of what is happening around you.”

But when thinking about the seasons, there is also a dimension of time. “Yes; because we are all subject to the passage of time. Take the example of the snowdrop; there is a cycle which renews itself every year. But it is not only that every snowdrop is different: every year, the same plant will produce flowers which are different from those of the previous year. So the cycle always comes back to the same spot, but it’s never exactly the same one. It is the same but different – another great mystery which the garden brings one to contemplate.”

From A Celebration of Nature; May, ‘The Song of the World’, which includes an aerial depiction of the Blackwood’s house and garden

The Process of Painting

.

Laura’s paintings are extremely delicate and meticulously observed. In A Celebration of Nature, many of the pages look almost like botanical drawings. Asked how much she works from life, she explains: “I do a lot in sketch books but these are really for recording things as they go along. I do paint directly from life but also from the image I have in my mind’s eye. I am not really trying to produce a scientifically accurate rendering. I have tons of reference books, but any expert in ornithology or botanical art could probably pick holes in my images. It’s much more about creating the feeling of the place, or a mood.”

So, is she aiming to express something she’s experienced herself? “Yes, when you walk about in a wood and you hear the noise that pigeons make, the rustle of the leaves, or when it goes quiet in the snow – these are wonderful feelings that I want to convey. But I also try to be accurate. When I drew the fungi in Celebration, for instance, I went out and gathered them and had them in front of me whilst I worked.”

What about more elusive subjects, like birds, which one cannot just take into the studio? “Well, on the whole I am drawing birds that we actually have in the garden, but they never sit still long enough. So in that instance I would refer to a book. But actually, there is a bit more to it than that. In the picture ‘The Song of the World’, for instance, the subject is the Black Cap that comes on the same day every year from Africa. It’s a tiny little bird, which starts to sing a wonderful, continually babbling song that goes on for weeks and weeks (see video right or below). On the horizon, I’ve drawn the curve of the earth which you couldn’t possibly see, but I did it to show that the bird has come from a long way away. The whole aim is not to just reproduce what I see, but to give a feeling of an extraordinary happening.”

Video: The Song and Calls of the Black Cap. 4:03 minutes

From The Kitchen Calendar: the kitchen in January

The Feeling of Home

.

The Kitchen Calendar is obviously a very direct expression of the passage of time, following as it does the seasons as they appear in the landscape. However, the work includes a further dimension, in that it introduces the inside of the house and what happens when produce from outside is brought in for cooking and eating. For Laura, this is an integral part of our experience of nature; when she worked with the local children, she would ask them to draw or paint a piece of fruit – a pineapple for instance – and then, when they were finished, to eat it.

So it is not just a matter of observing nature as it is, but also of participating in it? “Cooking and eating are processes by which things are continuously transformed,” she explains. “It is said that ‘everything eats and is eaten’. Nature is so generous: when a tree produces fruit, it does so, of course, to carry the seed which will perpetuate the species, but it bears far more than could possibly be necessary for that. So there is an excess, and this gives us the opportunity to create something extra – something that is even more beautiful, through cooking and then sharing it with other people.”

One aspect of this is the experience of preparing food – the difference between peeling a carrot oneself and buying it pre-prepared in a supermarket. Another is the appreciation of fruits and vegetables in their season. “If you have strawberries all year round, then they are not special. But if you have to wait until the summer, then the first taste is something you really appreciate. One of the things I have tried to depict in the calendar is the special quality of different foods by season; nettles, for instance, are one of the first things to appear in the spring, and it is traditional to make a soup from the new leaves. This is because they contain all the minerals and vitamins that we need to be restored after the losses of the winter.”

But perhaps the predominant theme of The Calendar is the sense of home, which, as Laura writes in her blog [/], is more than a physical place. “I have not just painted kitchens, but also fireplaces and dining tables – places where people can come together and be at ease. Many of the images have also drawn upon memories of particular moments: sitting on the back doorstep shelling peas in the heat of summer, or the hot steam rising from the boiling marmalade contrasting with the wintery world outside.” The theme of stillness also comes in here, as many of her pictures carry an extraordinary sense of repose. “Yes, I suppose so. I have tried to capture the feeling of home: there may be a dog asleep in front of the fire, or a cat looking out the window as the rain pours down outside. I think this sense of being at home is a universal human need. We need to remember this, when so many people are deprived of it these days.”

A rolling view of Laura Blackwood’s Kitchen Calendar:

To see more of Laura’s artwork and to purchase the 2020 Kitchen Calendar,

see her website www.laurablackwood.com

Image Sources (click to close)

Banner picture: From The Kitchen Calendar: July.

First inset: Laura in her studio.

All images in this article courtesy of Laura Blackwood.

Email this page to a friend

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

Video: Turning by Bulent Rauf and Diane Cilento. 47:29 minutes

Video: The Song and Calls of the Black Cap. 4:03 minutes

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

READERS’ COMMENTS

0 Comments