A Thing of Beauty _|_ Issue 18, 2021

A Thing of Beauty: The Audley Chantry Windows, Hereford Cathedral

Hilary Davies contemplates the work of stained-glass artist Thomas Denny which gloriously expresses the vision of the 17th-century poet Thomas Traherne

Thomas Denny is a stained-glass artist and painter who since the 1990s has made over fifty windows for churches and cathedrals, mostly in England but also in Germany, Scotland and Ireland. His themes have usually been scriptural, but in recent years he has also undertaken projects which commemorate the lives of extraordinary people. In 2007 he produced four windows for Hereford Cathedral which celebrate the work of the poet and visionary Thomas Traherne (1636–74), who was born in the town. In this article, the poet and writer Hilary Davies contemplates these intimate, vibrant works which, she feels, gloriously embody Traherne’s vision of the world as the manifestation of the divine, a “grand jewel… the beautiful frontispiece of eternity, the temple of God, the palace of His children.”

The small and rather squat cathedral of Hereford sits in its peaceful garth in the old centre of town; in the evening sun, the local sandstone turns a honey gold. Little here now betrays, to the untrained eye, the tumultuous history of this city and this building. Yet the cathedral’s architecture reflects its varied past, with examples of Norman, Early English, Perpendicular and neo-Gothic; the building has known looting, structural collapse, and unsympathetic restoration. Its chained library is the largest in the world and its most famous single treasure the 13th-century Mappa Mundi. All of these facts bear witness to the centuries of the town’s strategic and religious importance in the border country of the Welsh marches.

In 2007 another treasure was added to the cathedral’s fabric: the Traherne windows in the late 15th-century Audley chantry. Their artist-maker is the contemporary stained-glass artist, Thomas Denny, and the craftsman who cut, leaded and fixed them is his long-term associate, Patrick Costeloe; their subject matter is the 17th-century poet and theologian, Thomas Traherne, who was born in the city. Denny’s style is always densely allusive; he steeps himself in the texts, physical contexts and histories of his themes, which have included subjects as diverse as the composer Gerald Finzi [/], the Benedictine abbey builders of Tewkesbury [/], the Free Miners of the Forest of Dean, and the rehabilitated Richard III (see video right or below). This immersion allows him to bring an interpretative freshness to his work that is never slavishly illustrative. His ‘reading’ of Traherne reaches a pitch of intensity and subtlety of symbolism perhaps unequalled in any of his other work.

Video: St. Katharine’s Windows: The Life and Death of King Richard III by Thomas Denny. Duration: 11:18

The Discovery of Traherne

.

Before we look at the windows, the remarkable tale of how we come to know the name of Traherne at all is worth a little telling, for he was almost lost to future generations several times over. The only work he had published in his lifetime was an anti-Catholic polemic, Roman Forgeries (1673), and of the two more works now known to be by him – published later in the 17th century after his death – neither carried their author’s name. But in the winter of 1896, the bibliophile W.T. Brooke bought two manuscripts from an antiquarian barrow book dealer on the Farringdon Road in London. Initially the manuscript poems were thought to be by Henry Vaughan, but eventually some inspired literary detective work by the second-hand bookseller, Bertram Dobell, correctly located them as being by the same author as the Roman Forgeries.

The astounding process of discovery has just grown and grown in the 110 years since. Works by Traherne have been pulled from burning rubbish tips in Lancashire, identified in Canada and America, extracted from the labyrinthine fastnesses of the British Library and unearthed in Lambeth Palace by an academic sheltering from the rain. Nor is the work over, as Traherne scholars confidently predict more findings in the future. (For more on this extraordinary story, click here [/].)

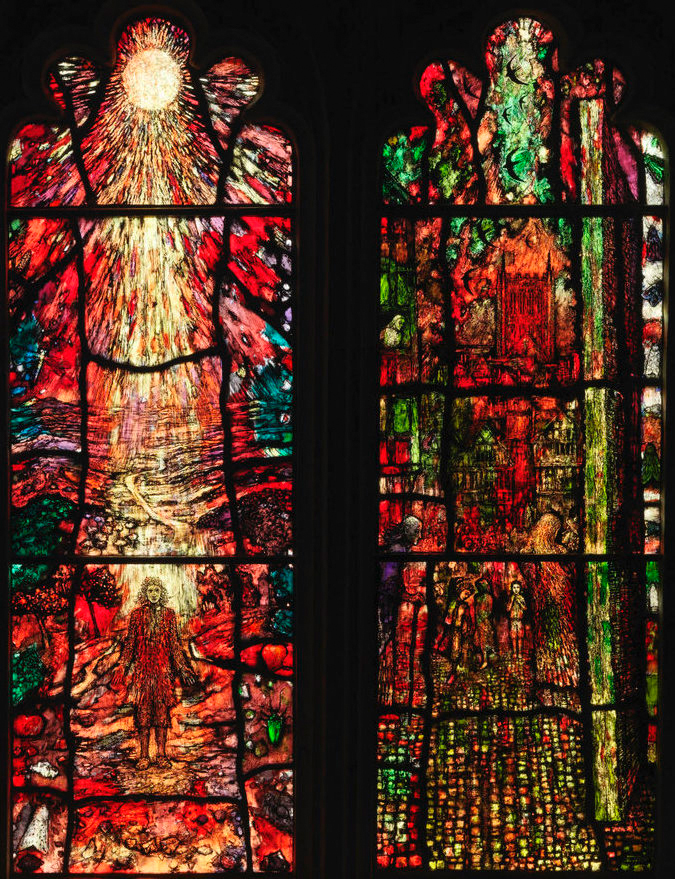

The westernmost windows. Photograph: James O. Davies, courtesy Thomas Denny.

Move your mouse over the image to enlarge

The Windows

.

In his poetry, and his prose meditations, Centuries of Meditations, Traherne presents a vision of the holy life in which the incarnate world is already our door to heaven if we perceive and attend to it aright:

The world shall be a grand jewel of delight unto you; a very Paradise; and the gate of Heaven. It is indeed the beautiful frontispiece of eternity, the temple of God, the palace of His children. [1, p.193]

In this approach to the divine, Traherne stands in a long tradition of what is known as ‘cataphatic theology’, from the Greek meaning ‘affirmative’, the knowing of God through how He has revealed His love in and for Creation:

Since God therefore was infinitely and eternally communicative, all things were combined in him from all eternity. [1, p.259]

This perception is experiential, sensual and spiritual all at once, and it is also relational.

Accordingly, the only appropriate response from humankind is a reciprocal love. All of these facets of love are beautifully realised in Thomas Denny’s windows. There are two of them, each with two lights, with above them both a central quadrifoil-form piercing flanked by two smaller ones – these last all depicting the different seasons and weathers of Britain. The main windows are surprisingly small, as their frame is the lower storey of the chantry, itself tucked away on the south side of the Lady Chapel. They are also at eye level so the visitor can easily see their minute detail, which is something normally denied by the very placement of stained-glass windows. So there is a kind of intimacy about them. This is admirably suited to Traherne’s vision, which prefigures Blake’s ‘Auguries of Innocence’ (‘To see a World in a Grain of Sand/ And Heaven in a Heaven in a Wild Flower/ Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand/ And Eternity in an hour’) in a most astonishing way: infinity, he says, of course knows no bounds and

… yet it must be expressed in a finite room… be infinitely expressed in the smallest moment by making me able in every moment to see them all. It is in both ways infinite, for my soul is an infinite sphere in a centre. [1, p.220]

The easternmost windows. Photograph: James O. Davies, courtesy Thomas Denny.

Move your mouse over the image to enlarg

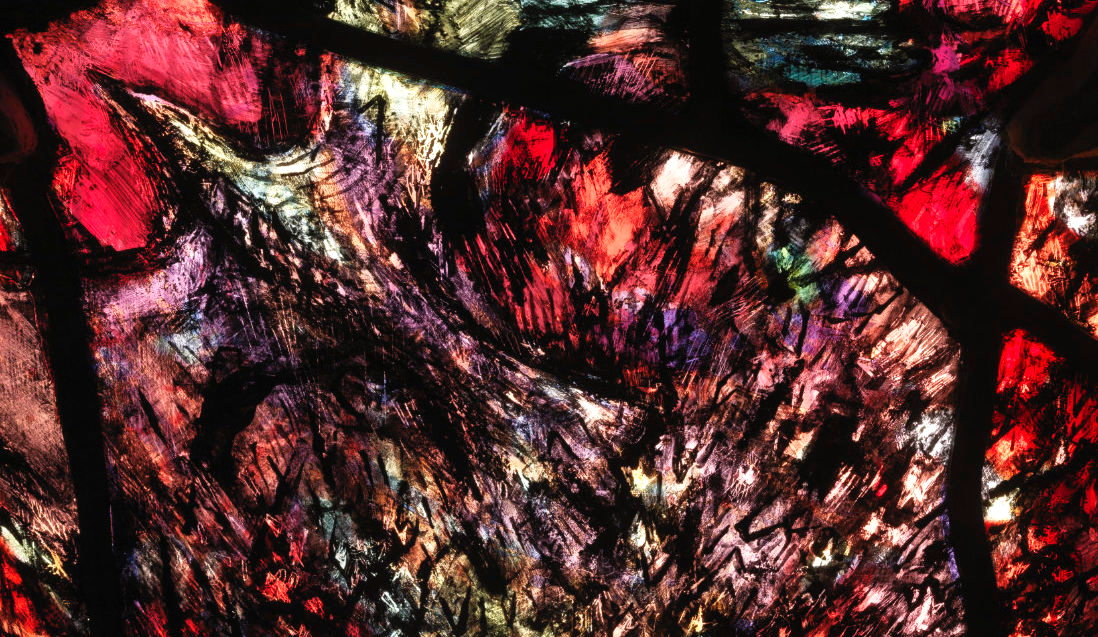

What strikes you upon arrival at the windows, in a vision worthy of the poet, is a simultaneous burst of colour imprinted with form, an intricacy of form infused with colour. Denny creates these effects by the superposition of flashed glass, which he then acid etches to remove as much of the original colours as he wishes for a particular effect; he will then paint on details of form, such as figures or landscapes, in black, and may also use silver stain in different densities to create anything from a deep bronze to almost white yellow light. The result is windows of astonishing complexity and richness.

Modern technologies have accustomed us in some degree to the phenomenon of colour separated from form, but this never occurs in the natural world. Colour in creation is therefore always incarnate; and traditionally it has often been associated with the living spirit of a thing, an attribute through which life glows. It is not without significance that, in the Anglo-Saxon Bible, ‘transfigured’ is rendered by the word ‘gehiwod’ or ‘hued, coloured’. Denny has suffused his windows with just that spirit, which is one of dynamism, fluidity and reciprocity, big movements of colour and minute observations of contour. Taken together, the four windows reveal a down-up, up-down flow – to use the word ‘structure’ might suggest a rigidity where there is none.

Detail from the westernmost windows: the figure of Thomas Traherne. Photograph: James O. Davies, courtesy Thomas Denny.

Move your mouse over the image to enlarge

Let us move from west to east (there is theology even in the orientation of the windows). The first light is dominated at the top by a great cream sun which sheds light in sparks and streams downwards in a central column through the window like a divine firework:

The sun, that gilded all the bordering woods,

_________Shone from the sky

______ To beautify

My earthly and my heavenly goods;

Exalted in his throne on high

____ He shed his beams

____ In golden streams…

Those floods of light which he displays

___ Did fill the glittering ways… [1, pp. 89–90]

As the light descends, it illuminates two elements in particular: the first is a standing man, his palms turned outwards towards the spectator in a gesture both of reverence and revelation. He is dressed in 17th-century clothes and clearly represents Traherne as we find him in the poem ‘The Salutation’:

___ And out of nothing now awake,

_These brighter regions which salute mine eyes,

________ A gift from God I take.

_The earth, the seas, the light, the day, the skies,

The sun and stars are mine; if those I prize. [1, pp.3–4]

The figure is backlit by a kind of halo. This then turns into a golden river that leads away into the landscape and upwards into the window. It is, like all the landscapes depicted in Denny’s work, both specific and universal, the river Wye at Hereford and the river that flowed out of Eden; it is also, quite literally in this window, the water that connects humankind with God:

The love from which it [love] floweth, is the fountain of love; the love which streameth from it is the communication of love… and the love which resteth in the object is the love which streameth to it. [1, pp.204–5]

Details from the westernmost windows: beetle and moth. Photographs: James O. Davies, courtesy Thomas Denny.

Move your mouse over the images to enlarge

The borders that surround this epiphanic centre are deep reds, turquoises, a green of especial viridity: beetles, moths, stones and precious minerals, fruits and trees and bushes, all bespeak the abundant, overflowing creation that Traherne celebrates.

Detail from the westernmost windows: Hereford. Photograph: James O. Davies, courtesy Thomas Denny.

Move your mouse over the image to enlarge

The Precious World

.

The second light in this window shows us a very precise manifestation of God’s generative power in the human world, one which is directly inspired by Traherne’s words. On the right we make out a massive door that has swung open on its hinges to reveal a townscape beyond: we recognise the tower of the very cathedral in which we are standing, but the houses that lie in its shadow are timber framed, crowding over the street. Denny may have based them on the best of the remaining 17th-century buildings in Hereford, the Black and White House Museum, which Traherne would have known. The fabric of the road is cobbled, but these are no ordinary cobbles: they are green, crimson, bronze and gold, the predominant colours of this light, ‘The dust and stones of the street were as precious as gold’.[1, p. 226]

This theme of the preciousness of seemingly ordinary things is one to which Traherne returns over and over again:

The choicest colours, yellow, green, and blue,

____Did on this court

____In comely sort

__A mix’d variety bestrew;

__Like gold with emeralds between; [1, pp. 90]

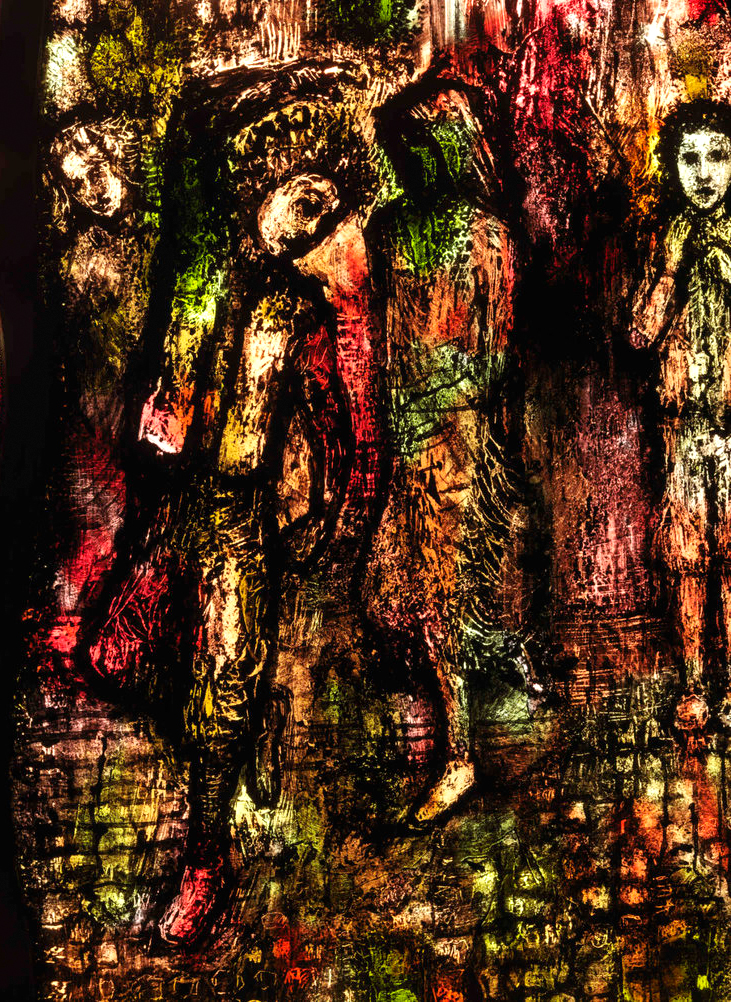

Detail from the westernmost windows: children at play. Photograph: James O. Davies, courtesy Thomas Denny.

Move your mouse over the image to enlarge

The patterning of the cobbles naturally draws the eye up to the middle ground, which is peopled with figures: an elderly, balding man with a walking stick, children playing, doing somersaults, a young man with his maiden – all the ages of man. Every one is to be found in perhaps Traherne’s most ecstatic celebration of creation in the Third Century of Meditations:

The men! What venerable and reverend creatures the aged seem!… And young men glittering and sparkling angels and maids strange seraphic pieces of life and beauty! Boys and girls tumbling in the street, and playing, were moving jewels.[1, p.226]

Finally, the movement of the scene carries us upwards to the verticals of the cathedral tower and the sky above: this is filled with darting swallows, synonymous with the return of summer and light and here used by Denny as an image of the Holy Spirit; once again one of the borders is decorated with bright-coloured flying insects.

God Is All Act

.

In the next window, all is dynamic movement: as Traherne says, ‘God is all act’ [1, p.259]. Our attention immediately focuses on the centre, a man running away from the observer through a field of wheat along a path that recalls the river of the very first light. This is a reference to one of the most famous sentences in Traherne, a sentence evoking transcendent being within what is present to the senses:

The corn was orient and immortal wheat, which never should be reaped, nor was ever sown.[1, p. 226]

Detail from the easternmost windows: the running man. Photograph: James O. Davies, courtesy Thomas Denny.

Move your mouse over the image to enlarge

The way leads upwards as if entering the secret places of a rounded hill which is quintessentially that of the rolling Herefordshire countryside, though it could also easily stand specifically for Credenhill where Traherne was rector at a particularly turbulent time in the Anglican church’s history (1657–72). Orchards, oaks, fruits and leaves fill the landscape with rich foliage greens and reds that resonate with the apple green and red sandstone of the previous light. Hanging in the distance above the dome of the hill is the tiny, but recognisable, skyline of Hereford itself, painted, almost drawn, onto the glass in minute detail in Denny’s trademark manner.

It is only gradually that we realise the whole scene emerges out of a deep green pool at the bottom of the window, symbolic of the water that gives eternal life:

_____And living water flows

Which Dives more than silver doth desire,

_____Of crystals far the best. [1, p. 88]

This source seems both literally and metaphorically to support all the life above it.

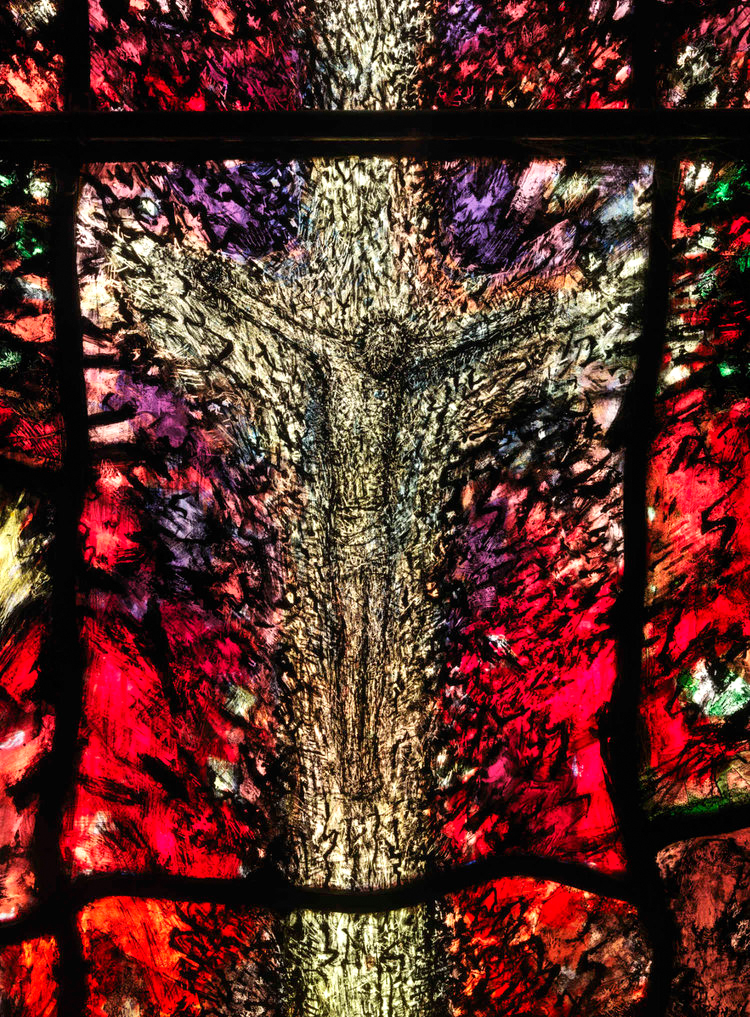

Detail from the easternmost windows: the living cross. Photograph: James O. Davies, courtesy Thomas Denny.

Move your mouse over the image to enlarge

The Living Cross

.

Finally, the diptych (for the two windows have something of this form) closes with the eastern-most light, which is dominated by red and pale yellow/cream, just as in the westernmost panel. As befits its position, it shows the crucifixion. Christ hangs on the cross, yes, but this is an extraordinary cross. It shoots up from the earth as a golden tree-trunk, a shining, living organism, scored with dozens of marks so that its bark appears to be moving, revealing the streams of sap beneath.

In this, Denny must surely have had in his mind, either consciously or subliminally, the Anglo-Saxon poem ‘The Dream of the Rood’,[2] in which the living cross narrates its story. The sole two branches are outstretched, supporting Christ’s arms; out of the crown, which resembles a head, a dove shoots towards the heavens.

Detail from the easternmost windows: the dove. Photograph: James O. Davies, courtesy Thomas Denny.

Move your mouse over the image to enlarge

The whole is set against a blazing backdrop of reds with their accompanying flecks of green; a stag, a leopard, a bull, birds like sparrows, symbolise the natural world, while obscure, tiny human figures are dwarfed by the enormity of the sacrifice being made for them. The circle, and cycle, of human and divine is thus closed: the dove carries redemption up from the earth towards the love of God that originated all of creation in the very first western light. In these remarkable windows, Denny gives concrete form, in the media of glass, colour and paint, to the vision of Traherne in the poem ‘The Circulation’ [/]. Here the poet tracks the unceasing and dynamic response of man and creation to God, God to man and creation:

__All things do first receive, that give:

Only ’tis God above,

__That from and in Himself doth live;

Whose all-sufficient love

__Without original can flow

__And all the joys and glories shew

Which mortal man can take delight to know.

_He is the primitive eternal spring

_The endless ocean of each glorious thing.

The soul a vessel is,

__A spacious bosom, to contain

__All the fair treasures of His bliss,

Which run like rivers from, into the main,

And all it doth receive returns again.[1, pp. 45–6]

Thomas Denny. Photograph: Alex J. Wright, courtesy of Thomas Denny

Denny has an excellent website which includes a comprehensive gallery of this work with wonderful pictures and films: www.thomasdenny.co.uk

Hilary Davies has published four collections of poetry from Enitharmon: the latest, Exile and the Kingdom, was published in November 2016. She is also a translator, essayist and critic. Hilary has won an Eric Gregory award, been a Hawthornden Fellow, has served as Chairman of the Poetry Society of Great Britain and is a Fellow of the English Association and The Temenos Academy. From 2012 to 2016 she was a Royal Literary Fund Fellow at King’s College, London and in 2018-9 at the British Library

Image Sources (click to close)

Banner: Detail from the Audley Chantry Window, Hereford Cathedral, showing the figure of Thomas Traherne. Photograph: James O. Davies, courtesty Thomas Denny.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] THOMAS TRAHERNE, Selected Poems and Prose (Penguin Classics, 1991).

[2] See for example, The Dream of the Rood, ed. Arthur Stannborough Cook (Franklin Classics, 1918).

Video: St. Katharine’s Windows: The Life and Death of King Richard III by Thomas Denny. Duration: 11:18

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

A Thing of Beauty…

The Chagall Peace Window and the Meditation Room in the United Nations building, New York

Beauty Happens

Ornithologist Richard Prum challenges the orthodox view of evolution to argue for the importance of beauty, pleasure and desire in shaping the natural world

Mary, Seat of Wisdom and Mercy

Jane Townes explores the imagery of the Virgin Mary in the stained glass of Chartres Cathedral

A Thing of Beauty…

James Turrell’s installation at Dorotheenstädtischer Friedhof, Berlin

READERS’ COMMENTS

The philosopher Junayd wrote “the colour of water is the colour of the vessel which contains it”>

These wonderful images of colour and containment give a depth of reflection of timelessness and movement of the light. I hope to visit before too long.

Wonderful, thanks. Hope to visit soon