Metaphysics & Spirituality _|_ Issue 28, 2025

Unlocking the Heritage of Tibet

Dylan Esler talks about the ancient contemplative tradition of Dzogchen Buddhism – the ‘effortless path’ – and the 84000 Project, which is preserving the precious heritage of Tibetan Buddhism

Unlocking the Heritage of Tibet

Dylan Esler talks about the ancient contemplative tradition of Dzogchen Buddhism – the ‘effortless path’ – and the 84000 Project, which is preserving the precious heritage of Tibetan Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhism is one of the world’s great spiritual traditions, with an unbroken line of transmission and a written heritage going back to the 8th century and beyond. Since the country was annexed by China in the 20th century, its traditions have continued to develop and flourish in exile. Dr Dylan Esler is a scholar and translator who is currently working for the 84000 Project [/] – an ambitious enterprise which aims to translate the entire Tibetan Buddhist canon of texts into English. He is also a practising Buddhist in the Nyingma / Dzogchen tradition which emphasises intrinsic awareness of the nature of mind. His most recent work is a translation of an early text by the 10th century Dzogchen master Nubchen Sangye Yeshe, Lamp for the Eye of Contemplation,[1] as well as a study of the same author’s early Dzogchen commentaries, entitled Effortless Spontaneity.[2] He talked to Jane Clark and Pheobe Ryrko about the specific features of Dzogchen and the aims of the 84000 Project.

Jane: Could you tell us a little bit about how you came to be involved in Buddhism, and in particular, how you became drawn to the Dzogchen tradition?

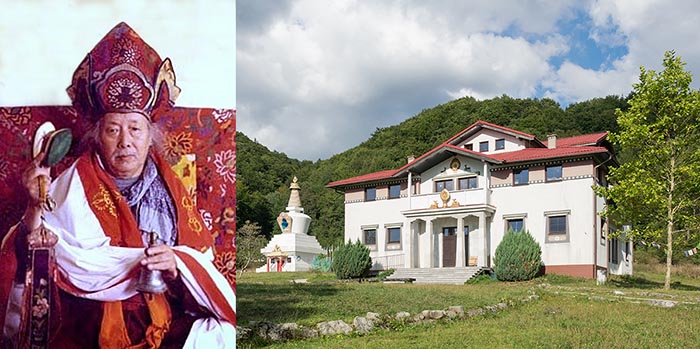

Dylan: I became interested in Buddhism at a very young age, maybe when I was 13 or 14. At that time, The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying by Sogyal Rinpoche [3] had just recently come out. I read that, and it led to my meeting with several Tibetan masters, including Sogyal Rinpoche himself. But the real trigger was my meeting with my main teacher, who was Chime Rigdzin Rinpoche [/], who died in 2002. I met him when I was 16, when he was already an old man. He was otherwise known as C. R. Lama.

He was a very unconventional character, and his way of teaching was quite unique in that he didn’t sit down to give detailed, structured talks about various Buddhist topics. It was more a matter of being in his presence and performing a series of long ritual practices that he had translated back in the 70s and 80s when he was a professor in Shantiniketan in India. In this context, he would give a kind of non-verbal, very powerful transmission through his blessings. It was all a very formative experience. I suppose my subsequent interest in studying Buddhism more academically arose out of this encounter and perhaps out of a desire to somewhat make sense of it all. He was a Nyingma master and a master of Dzogchen, so there was a connection with that tradition from the very start for me.

Jane: Could you tell us a little bit about how you came to be involved in Buddhism, and in particular, how you became drawn to the Dzogchen tradition?

Jane: Could you tell us a little bit about how you came to be involved in Buddhism, and in particular, how you became drawn to the Dzogchen tradition?

Dylan: I became interested in Buddhism at a very young age, maybe when I was 13 or 14. At that time, The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying by Sogyal Rinpoche [3] had just recently come out. I read that, and it led to my meeting with several Tibetan masters, including Sogyal Rinpoche himself. But the real trigger was my meeting with my main teacher, who was Chime Rigdzin Rinpoche [/], who died in 2002. I met him when I was 16, when he was already an old man. He was otherwise known as C. R. Lama.

He was a very unconventional character, and his way of teaching was quite unique in that he didn’t sit down to give detailed, structured talks about various Buddhist topics. It was more a matter of being in his presence and performing a series of long ritual practices that he had translated back in the 70s and 80s when he was a professor in Shantiniketan in India. In this context, he would give a kind of non-verbal, very powerful transmission through his blessings. It was all a very formative experience. I suppose my subsequent interest in studying Buddhism more academically arose out of this encounter and perhaps out of a desire to somewhat make sense of it all. He was a Nyingma master and a master of Dzogchen, so there was a connection with that tradition from the very start for me.

Jane: Where did you meet with him? Presumably not in India?

Dylan: C.R. Lama would come to Europe every year where he had a small community of disciples, and he would travel around different places. He had students in the UK, in France, in Germany, in Switzerland. His main European monastery, which was being built at the time, was in Poland, and he also established a monastery in Siliguri, India, which was his main seat. The first time I met him was in Poland, and then I would try to travel whenever possible to receive his teachings in these various places.

Later, after finishing my MA at SOAS in London and before embarking on my PhD in Louvain, and also while working on it, I studied closely with another very learned lama and scholar of the Nyingma tradition, Lopon P. Ogyan Tanzin Rinpoche, for several years. He himself, when he was younger, had studied and worked with C.R. Lama in Shantiniketan, and his main teacher was the late Dudjom Rinpoche. I was fortunate to spend extensive periods of time living with him and his family in Sarnath, India, the place where the Buddha had given his first sermon.

Jane: Your present area of research is into the early origins of the Dzogchen tradition. Can you say something about Dzogchen and what distinguishes it from other forms of Buddhism?

Dylan: Dzogchen is a tradition of contemplative practice that was formed in Tibet, possibly with roots going back to India, but mainly codified in Tibet. One of the important figures in this process of codification was the ninth/tenth century master Nubchen Sangye Yeshe, whose work is the specific subject of my research. There were others before him, but he was really very important in establishing Dzogchen as an independent vehicle.

The Dzogchen tradition is considered the topmost approach to meditation within the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism, and also within the Bon tradition, which is nominally non-Buddhist and also refers to the ancient indigenous religion of Tibet. I would say that the most fundamental feature of Dzogchen is that it is about recognising the nature of mind. Our mind is a constant stream of thoughts, feelings, emotions and so on, but beyond all that is what we call ‘the nature of mind’ or rigpa, which is sometimes called ‘intrinsic awareness’ or ‘the enlightened mind’. This is completely untouched by any of these thought processes.

So the whole point of the Dzogchen approach is to recognise the nature of mind – the nature of intrinsic awareness – and then to learn how to remain within that recognition. That is really what the practice of meditation is about – to not become distracted by whatever thoughts etc. may arise, but to allow them just to arise and dissipate.

Left: C. R. Lama. Right: Gompa Drophan Ling in Darnków, Poland, founded by C. R. Lama in 1995. Photograph: Jacek Halicki [/] via Wikimedia Commons

An Effortless Path

.

Phoebe: Dzogchen is often called ‘effortless path’. Could you say more about that?

Dylan: Yes, one of the very important characteristics of Dzogchen is that meditation should always be effortless. Effortlessness is really a hallmark of its approach, not only in terms of its goal, but also in terms of practice. I mean by practice that it becomes integrated into conduct, that is, the activities of daily life. But of course, before being able to do that, one has to learn to remain undistractedly in this state of awareness of the nature of mind, which is what meditation is about.

In practical terms, because this may seem somewhat abstract, what usually happens is that a master will introduce the student to the nature of their own mind. This form of transmission can take different forms. It can happen in a ritual setting as part of a tantric initiation or empowerment, but it can also occur in the most unexpected of day-to-day circumstances where the master will kind of shock the disciple into letting go of their ordinary thoughts, etc., so that they can gain a glimpse of the nature of mind. Sometimes the glimpse will be very fleeting, but the point is always to return to that experience and to learn to prolong one’s ability to remain within that state undistractedly.

Jane: In my reading, I have also come across the suggestion that at the heart of Dzogchen is the idea of cutting through illusion, or cutting through what seems to be translated as ‘dumbfoundedness’.

Dylan: Absolutely. Yes. This cutting through is really about breaking through the tendency to reify and solidify things. If we talk about the relevance of the Buddha’s teaching in our contemporary situation, there are many ways in which we may regard it. On one level, it can simply help people to become better human beings, because there’s a lot in the teachings about how to develop kindness and compassion. Also, how to reflect on impermanence and not to run away from it. Rather, to come to understand that the acceptance of impermanence can be a very important lesson, which makes our lives more meaningful.

But more fundamentally, I would say that what really makes the Buddha’s teaching unique is its relentless insistence on non-substantiality, meaning that nothing can be reified and made concrete or substantial, whether we are talking about the external world of phenomena or our own concepts of being who we are as an individual. So Dzogchen is a very direct approach of cutting through any and all tendencies to solidify things.

Jane: This idea of insubstantiality is coming out very, very strongly in contemporary science now. Many of the scientists and philosophers we have spoken to in the magazine are coming from this perspective. For instance, Ian McGilchrist called his magnum opus The Matter with Things [3] (see our interview). What he implies is that we think in terms of ‘things’ rather than process or flow, and this is the root of our problems. Would you say that Dzogchen is also a perspective of non-duality?

Dylan: Yes, quite. I think that non-duality is actually, again, one of the hallmarks of Dzogchen doctrine in many ways. Non-duality, of course, has many dimensions. On one level we can talk about the non-duality of subject and object. When we are in the dichotomy of being a subject here, looking out at objects there – this is a reifying or solidifying perspective. We can then become caught up in reactivity, because those objects that are good for me are things that I want more of, so I try to grasp them. At the same time, I try to push away objects that threaten my comfortable sense of being who I am. So we have an inbuilt mechanism of attachment and aversion that is premised on ignorance – by which I mean, ignorance of who we really are. Once we learn to dissolve that sense of having to react to whatever occurs, then we open up to a more spacious perspective, and that is the perspective of non-duality.

The Green Tara, a representation of fearless compassion. Her right hand is extended as a gesture of generosity and her left leg steps forward to show her engagement with the world. 13th century tanka from Nepal. Image: Himalayan Art Resources. For more details, click here [/].

Move your computer mouse over the image to enlarge

The Resonance of Compassion

.

Phoebe: Can we really make a distinction between the cultivation of compassion and the understanding of the nature of mind? In my understanding, the outcome of the melting, or dissolving, of one’s solidity is compassion. The final outcome of all the practice is a loving heart. And that’s where Buddhism finds common ground with other traditions, such as Christianity or Islam.

Dylan: Quite. Compassion is actually considered to be, you could say, the very resonance of the nature of mind. So once one dissolves the tendency to solidify and reify, everything keeps coming back to emptiness and spaciousness and openness. But this emptiness isn’t just some kind of inertia; there’s a resonance with compassion. Compassion is not something that’s added on, such that it is an effort to be good and kind, but it’s rather the spontaneous expression of the nature of mind. Following on from that, it is then the ability to act appropriately in whatever circumstances may arise without having to follow a rule book.

You mention overlap with other spiritual traditions. I think there’s a lot to be said for pursuing comparative religion in a spirit that takes account of the contemplative traditions. If we are able to do that, then we can really get to a much deeper dimension. And we can point towards places of profound convergence, such as you were mentioning – a perspective of non-duality, which is also a perspective of natural, innate compassion and kindness. Even in terms of structuring principles of contemplative practice itself, I think there’s a lot to be pursued in this direction. So it’s wonderful that the magazine has this line of inquiry.

Jane: You have mentioned that, actually, Dzogchen may not be confined to Buddhism; it could also be said to be happening in other contemplative traditions, or maybe it would be better to say that it is speaking to a level where, as you say, these traditions converge at an experiential level, at the level of non-duality. Do you think that it, therefore, has a particular relevance at this time, in a world where people are tending not to go for religious traditions in a formal sense, or even rigorous practice?

Dylan: I think that potentially it certainly does have – although it’s maybe important to say first that it is what one would call an esoteric tradition in that it’s transmitted via personal connection between master and disciple. So whatever relevance it might have for the contemporary world, that aspect of the transmission would certainly need to be preserved. Otherwise, one would risk really losing the essence of it.

But, yes, given that, I think Dzogchen has a great pertinence for the present time. People nowadays are less attracted to traditional religious practices or to very complex rituals, and the attractive thing about Dzogchen practice is that it tries to get to the essence of things. So while it can be transmitted and is often – and even mostly – transmitted within a traditional ritual framework, it can be quite independent of that.

It is actually a very simple form of practice, although that doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s easy. While it’s an effortless type of meditation with very little in terms of technique, nonetheless, the practitioner has to learn to remain settled in this natural state of intrinsic awareness without being caught up in the habitual tendencies of distraction. So it’s certainly not an easy practice. But it is very simple, and due to its simplicity, I would say it has the potential of being integrated perhaps more easily into the conditions of the modern world. Or perhaps it would be better to say integrated into the life of someone living in the conditions of the modern world.

Jane: You don’t necessarily have to be a monk in a monastery or suchlike in order to practise this kind of meditation.

Dylan: Oh no. Even in Tibet itself, some of the great Dzogchen masters were not monks, but they were married, they had family lives and various responsibilities, etc.

Details from an extraordinary series of 17th century murals in the Lukhang Temple in Lhasa, Tibet, depicting Dzogchen practices. Image: From a video of an exhibition of tantric art at the Wellcome Foundation in London. Click here [/] to watch the first part of the video (duration 4:28).

Move your computer mouse over the image to enlarge

Conduct in the World

.

Jane: You say that this state of being settled in intrinsic awareness becomes integrated into conduct in our everyday life. You have a very thought-provoking quote about this:

The view should be higher than the sky, yet one’s conduct and attention to karmic consequences finer than barley flour.

Dylan: This is a quotation attributed to Padmasambhava [/], the great tantric master who was responsible for establishing Tantric Buddhism in Tibet. It makes a very important point. What is special about Dzogchen is that within that tradition, it is not a matter of following fixed rules of conduct or of conforming to a fixed ethical framework. The emphasis is on remaining in the state of awareness of the nature of mind and being responsive to whatever presents itself to you in the moment. There’s not really a need to impose external rules of behaviour.

In Tibet itself, the school was often criticised on this matter, because it was perceived as being dangerous due to the seeming dissolving of moral structures. Of course, this works well when we are really attuned to this state of intrinsic awareness. But if we are distracted, and if we are just following the push and pull of the impulses of attachment and aversion, then we fall into the ordinary conditions that make up what in Buddhism is called ‘samsara’ or cyclic existence. In The Lamp for the Eye of Contemplation, Sangye Yeshe is very stern in his warnings against such misguided yogins, and he has some very harsh words for them.

Jane: So there must be some safety nets in place to guard against self-delusion?

Dylan: Yes, of course. The most important one is probably that this transmission occurs in the relationship between a master and their disciples. And so the master will check up on the student and make sure that they don’t get too carried away – thinking that they’re enlightened, for instance, when they are not.

Sangye Yeshe goes to great lengths to discuss the indications that may arise when a person engages in meditative practices for prolonged periods of time, as these can sometimes be a great help in determining whether they are practising properly or not. But at the same time, he’s very careful to say that we shouldn’t become attached to these indications either, because then we could start to be in the position where we are meditating in the hope of receiving certain indications, visions or nice dreams, etc. Sometimes the indications that are the most pleasant are actually the most misleading. It’s also important not to get too caught up in the dichotomy of ‘hope and fear’, etc.

I think the basic Buddhist vows are also a form of safety net, so that one knows, for instance, that engaging in certain ways of behaviour will have negative repercussions, and so it’s better to avoid such forms of conduct.

Phoebe: What do you think about the relationship between Dzogchen and other forms of Buddhist practice? Within Tibetan Buddhism, for instance, the idea of empowerment and the passing on of knowledge through ritual has a very central place.

Dylan: This is a very relevant question when discussing the way that Dzogchen can be transmitted in the Western context. Theoretically, Dzogchen can be practised as a self-sufficient path in its own right. That’s very much how Sangye Yeshe expounds it in the two books of his that I have translated. But at the same time, it is clear that he himself was also a master and a practitioner of the tantric traditions which form the usual practices of Tibetan Buddhism. So although he is very keen to establish Dzogchen as an independent vehicle and he was, in a sense, one of those responsible for its codification in practical terms, he was at the same time transmitting tantric methods and practising them.

In fact, it is clear that throughout Tibetan history, I wouldn’t say all without exception, but the vast majority of Dzogchen practitioners have also, in one way or another, practised within the structures of the tantric tradition. I think one reason for this is quite simply that the tantric practice works well as a method, and it has the potential to open someone up to something like the spaciousness and effortlessness of Dzogchen.

For instance, when in tantric practice we visualise ourself as a deity and our world or our life-world as a mandala palace, we aren’t creating something that doesn’t exist; rather, we are actually returning to the way things really are. Dzogchen is also about returning to where we really are, to the ground of our being, except that in Dzogchen, the emphasis is directly on the recognition of intrinsic awareness. So it’s not so much a matter of imagining this perfection as a Buddha figure with which one identifies, but rather of letting go of all mental clutter and activity and relaxing and settling into the state of intrinsic awareness. So the combination of tantric practices with Dzogchen meditation can work quite nicely together, and these practices come to support one another.

Pages from the Kangur, ‘The Translated Words (of the Buddha)’, from the Dangkarla Temple Archive. Image: Buddhist Digital Resource Center (BDRC), accessed 19 May 2025

The 84000 Project

.

Jane: Another line of research that you are currently involved in is the 84000 Project, whose aim is to translate the entire canon of Tibetan Buddhism into European languages.

Dylan: Yes, it’s a wonderful project to be part of. Its origins go back to, I think, March 2009, when Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche convened a conference in Bir in India, where he invited all the great Tibetan lamas and lineage holders and scholars, as well as Western academics specialising in Buddhism and translators of Tibetan Buddhist texts. He presented the people there with a challenge. He pointed out that if we want to preserve, or even understand, the Buddhist texts which are written in classical Tibetan, there is a kind of urgency to translate them into English. This is because, within a few generations, it’s likely that very few people, whether Tibetans or Western academics, will be able to read classical Tibetan and thus have access to this treasury of Buddhist wisdom and classical Buddhist knowledge.

Subsequently, a small working group was created and this led to the establishment of 84000. It’s a non-profit, global organisation that has the aim of translating the whole Tibetan Buddhist canon. This is divided into two major parts. There’s the Kangyur, which is the words of the Buddha, and the aim is to translate that by 2035. And then there’s the Tengyur, which are the Indian commentaries on the words of the Buddha. This is to be translated by 2110. So it’s a very vast project in its scope; there are about 230,000 pages of text altogether. The task is not just to translate all this material, but also to make it available for free via a digital format, so part of the project is to create an online reading environment, a reading room where the texts interlink among each other and link to glossaries and other digital study aids (click here [/] to explore these on the 84000 website).

Pheobe: You are engaged as a translator on this project?

Dylan: Quite. They had started out by giving grants to translators, enabling them to focus on particular texts and translate them into English. But in recent years, the organisation has moved from a project-based model to one with permanent translators and editors. That was the point at which I joined it, in 2022, so I’ve been working there now for three years, almost. Just to give you an idea of the work that has been done: I think when the project started, less than 3% of the Kangyur had been translated, and now it’s 48%. That gives you a sense of the pace of the work.

Jane: Is the heritage complete? I remember having a conversation some years ago with Akong Rinpoche at the Samye Ling Centre about a project they were running there. He was rescuing manuscripts which had been lost in the Chinese invasion. It seems that the Chinese specifically targeted libraries and suchlike in an attempt to destroy Tibetan culture, but monks and librarians, and in some cases village people, had rescued them from the flames or smuggled them out to save them.

Dylan: The 84000 project is really about what we call the ‘Tibetan Buddhist canon’, but there are many other Tibetan texts that are not included in the canon as such. The work on Dzogchen we have just been talking about, by Nubchen Sangye Yeshe, is not part of it, for instance. The Buddhist Digital Resource Center, the BDRC, which used to be the Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center [/], has been doing extraordinary work in salvaging and scanning and making digitally available copies of texts that would otherwise have been completely lost and forgotten.

The canon we are working on is in a complete form. It’s maybe important to say, though, that there are different Buddhist canons. There’s also a Chinese canon, a Pali canon and so on. And even within the Tibetan tradition, there are different branches, each with its own recension. The 84000 project has taken the decision to use as its reference point the Degé canon, which was compiled in the 18th century. But of course, when we work on specific texts, we will almost always be comparing different versions in different recensions or even different languages. So if there’s a Sanskrit original manuscript or a parallel Chinese translation available, then we’ll compare it with that.

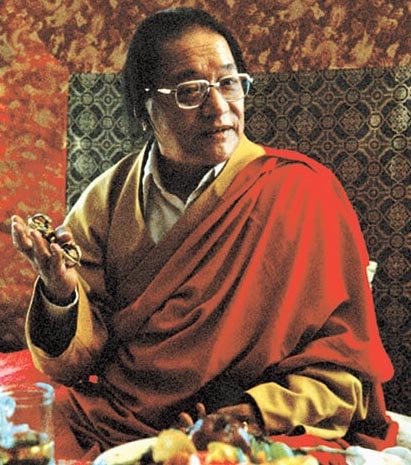

Dudjom Rinpoche (1904–1987), an important transmitter of the Nyingma tradition to the West. Considered to be the living representative of Padmasambhava, he was a great revealer of the ‘treasures’ (terma [/]) concealed by Padmasambhava

The Treasures

.

Phoebe: Thinking of the relevance of the teachings to our present-day world, I understand that within Tibetan Buddhism there is specific process through which knowledge was laid down in the past by the ancient masters in preparation for the future. These are referred to as ‘treasures’. Can you say more about this?

Dylan: I should just start by clarifying that the works that are being translated in the 84000 project are not considered to be treasures as such, according to the Tibetan taxonomy. They are, of course, treasures in the wider sense of being treasures of spiritual wisdom and knowledge for humanity. But in the Tibetan tradition, the word terma has a very specific meaning, referring to texts or objects that were hidden at a particular time, usually by Padmasambhava but also by others, to be rediscovered at a later point by an appointed disciple. These are usually a disciple of Padmasambhava, who reincarnates at the right time to discover the treasure. This often happens through a kind of visionary quest which involves dreams and visions, etc., that lead to the place of discovery.

There are different kinds of treasures. There are treasures that are hidden in the landscape, in rocks or mountains or lakes. But then there are also treasures that are hidden in the minds of the disciples, so these are treasures where there’s no physical trace as such.

Phoebe: So these are wisdoms which were specifically hidden to be discovered by later generations?

Dylan: Within the discipline of Tibetology there have been varying ways of looking at these treasures. In the 70s and 80s, the tendency was to see them as basically having been composed or written by the treasure discoverer. So they were regarded as the authors of the treasures. But more recent research has shown that in some cases at least, treasure discoverers were just compiling, editing and maybe partly rewriting or rearranging texts that had been physically discovered or received in some way. For instance, we find bits of text that have been rediscovered several times over the centuries.

This seems to indicate that the treasures are exactly what they claim to be – a kind of recompilation and editing of earlier material but adapted to new circumstances. And perhaps this tells us something about why people go about discovering such material. When we compare treasures that have been discovered at different times, we find that there are parts that are very conservative in the sense that they simply reproduce earlier material, albeit in a new setting. But we also observe stylistic differences between treasures that have been revealed in, say, the 18th century, compared to those that have been revealed in the 14th. So there is some level of difference between them.

So the question arises: Why reveal such material again and again? And the answer is so that the blessings associated with these texts are refreshed. If you have a very short lineage going from a treasure revealer to their disciples, the blessings are very powerful and fresh.

Jane: Whereas a lineage stretching back to Padmasambhava in the 8th century would perhaps feel very remote? So would you say that this is basically a way of bringing the ancient knowledge and principles into the present time?

Dylan: Absolutely. Yes. It’s adapting these archaic materials to new settings, new circumstances, infusing them with the fresh blessings of a treasure discoverer who, after all, is considered to be the reincarnation of a disciple of Padmasambhava, and so has a direct connection to him, as it were. To give some recent examples, my own teacher, C. R. Lama, was actually a tertön who discovered some treasures. More prominently, perhaps Dudjom Rinpoche [/], who died in 1987 and did so much to preserve and revitalise the Nyingma tradition in the contemporary world, was a very prolific discoverer of treasures. So, this process of discovering teachings that are connected to the ancient wellspring yet adapted to present times and infused with fresh blessings, is something that is continuing to happen down to the present.

Phoebe: So it maybe has a very particular function as the tradition has established itself outside of Tibet, in what is a very different cultural setting.

Dylan: Yes, maybe. I should also mention Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche [/], who died only a few years ago in 2018. He did a lot to make the Dzogchen tradition known in the Western context and discovered many treasures, which in his case were what are called mind treasures or intent treasures – treasures that are not found in a physical sense but discovered in the mind.

Jane: So, to bring our conversation to an end, what do you think is the main message that the Dzogchen tradition has for the contemporary world?

Dylan: Well I think we’ve covered a lot of ground in this relatively short time. If I had to summarise, I would say that the key point of the Buddha’s teachings for the modern world is the emphasis on non-substantiality and non-reification. And in terms of Dzogchen, it is the emphasis on a path of effortlessness.

Jane: Dylan, thank you so much for talking to us about this profound tradition and your work on translating this precious heritage so that everyone can benefit from its wisdom.

The Tibetan letter ‘A’ within a rainbow is a common symbol of Dzogchen

Image Sources (click to open)

Banner: Guru Rinpoche Padmasambhava, the founder of Tibetan Buddhism. 19th century tanka held at the Rubin Museum, USA. Image: Himalyan Art Resource. Click here [/] for more details.

Inset: Dylan Esler, courtesy of himself.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] DYLAN ESLER (trans.), The Lamp for the Eye of Contemplation: The Samten Migdron by Nubchen Sangye Yeshe, a 10th-century Tibetan Buddhist Text on Meditation (Oxford University Press, 2022).

[2] DYLAN ESLER (trans.), Effortless Spontaneity: The Dzogchen Commentaries by Nubchen Sangye Yeshe (Brill, 2023) Open Access: https://brill.com/display/title/63340.

[3] SOGYAL RINPOCHE, The Tibetan Book of the Dead, (HarperCollins, 1992).

The text of this article has a Creative Commons Licence BY-NC-ND 4.0 [/]. We are not able to give permission for reproduction of the illustrations; details of their sources are given in the captions.

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Maintaining a Radical Edge

Dharmacharini Suryagupta, Chair of the London Buddhist Centre, talks about the transformative power of Buddhist principles in the contemporary world

Choje Akong Tulku Rinpoche

Vin Harris talks about the life of a remarkable man, founder of the Samye-Ling monastery and an instrumental figure in bringing the traditions of Tibetan Buddhism to the West

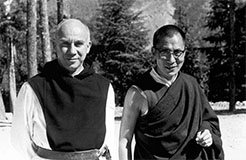

The Engaged Contemplative Spirituality of Thomas Merton

Jim Griffin surveys the life and work of the great 20th century visionary

Mind over Matter

Scientist and philosopher Bernardo Kastrup discusses his critique of the materialist paradigm and argues that consciousness is the underlying reality of the universe

READERS’ COMMENTS

Very interesting. Prayers, Alan

My Buddhist experiences have been highly enlightening. Prayers, Alan

Thanks for the great article! The deep heritage of Tibet and Dzogchen philosophy inspire us toward calm and reflection in a fast-changing world.