News & Views

Book Review: The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer

Martha Cass contemplates the message of a new book that advocates ‘an economy of gifts and abundance’

The Saskoon Serviceberry (Amelanchier alnifolia [/]). Photograph: Allison Dumas [/] / Alamy Stock Photo

Why, asks Dr Robin Wall Kimmerer, do we permit the dominance of an economic system that assumes scarcity, and actively harms what we value? In this very short book – which first appeared as an extended essay [1] – she puts forward an alternative to the usual growth-focused model. Known as the ‘gift economy’, this mode of exchange has been marginalised in industrialised cultures, but it was and is prevalent in many indigenous societies. Its aim: to maintain beneficial relationships, cultivate abundance and promote mutual thriving.

Kimmerer, who is a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, within the larger Anishinaabe group of tribes in the northern US and southern Canada, explains the central idea as follows:

In a traditional Anishinaabe economy, the land is the source of all goods and services, which are distributed in a kind of gift exchange: one life is given in support of another. The focus is on supporting the good of the people, not [the] individual. [p. 8–9]

Further, she points out, the receiver of these gifts is thereby bound to a kind of positive, freely given restraint; the receiver is expected to assume the ‘attached responsibilities of sharing, respect, reciprocity, and gratitude.’

Kimmerer is also a botanist and the author of two previous books – Gathering Moss [2] and the international best-seller Braiding Sweetgrass [3] – which explore the interface between indigenous worldviews and the contemporary scientific stance. In The Serviceberry, she looks at social systems, taking as inspiration a particularly prolific type of berry, Amelanchier alnifolia, whose common names include shadberry, juneberry, saskatoon, or serviceberry. A native of western North America, it reliably produces masses of berries each year, far more than it appears to need and enough to feed scores of birds, insects, and animals, including humans filling buckets and happily staining their fingers blue. It amply does its part in sustaining and maintaining the world.

Curiously, the name ‘serviceberry’ does not derive from the plant’s many services to its community. Rather, it is derived from ‘sorbus’, a related genus of trees and shrubs in the rose family – ‘sorbus’ became ‘sarvice’ by some slip of the tongue, and this became, in turn, ‘service’. But it is an apt slip. In the Potawatomi language of the Great Lakes region, the name for the plant is bozakmin – ‘best of berries’ with the ‘min’ particle meaning both ‘berry’ and ‘gift’. Serviceberry is the supreme gift-giver.

World as Gift

.

However, Kimmerer goes on to explain, in the Anishinaabe worldview, it is not just fruits that are understood as gifts: it is…

… rather, all of the sustenance that the land provides, from fish to firewood. Everything that makes our lives possible – the splints for baskets, roots for medicine, trees whose bodies make our homes and the pages of our books… When we speak of these not as things, or natural resources, or commodities, but as gifts, our relationship to the natural world changes. [p. 8]

Further, in this system, she suggests, there is nothing that is not a gift. Gift is the order of the world.

Clearly, it is rude not to give thanks in some way when one has received a gift, and bad manners to be greedy and take too much, or to waste what we have been given. In communities based on gift economies, this kind of rudeness is acutely felt, as there is the danger that essential relationships, upon which all mutual thriving is based, could be compromised. Rudeness does not go unnoticed, therefore, and the consequences of it are never pleasant.

On the other hand, enumerating the gifts we receive, remembering them and thanking the Giver have their own reward. As well as being good manners, this also creates a sense of fulfilment, of abundance. As Kimmerer puts it, ‘Gratitude and reciprocity are the currency of the gift economy.’ [p. 14] They create their own kind of wealth.

She notes, too, that gift economies are not only to be found in indigenous societies; they also appear within capitalist economies, in certain situations. They emerge, for example, when we are in the grip of a crisis. When the dominant economy is ruptured by, say, an earthquake or flood, the gift economy immediately flows in to take its place. In a collective emergency we give what we can of labour, time, goods and money, to save survivors, shelter the needy, and so on. No one waits to act until the market stabilises. The gift economy is there, ready and waiting.

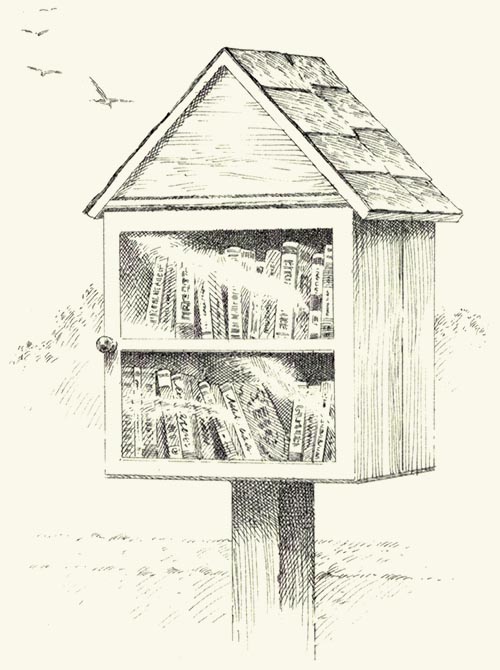

It is also there in more peaceful times, in the form of small improvisations like free book kiosks, free roadside vegetable stands, potluck suppers, clothing swaps, seed exchanges and cashless transactions on the internet.

But for me, there is an undeniable sadness, and a frustration, in enumerating these tiny remnants of gift economies within a capitalist milieu. These phenomena are in the margins of our lives. After the clothing swap or potluck supper, the market-mind returns. As Kimmerer observes: ‘when something moves from the status of a gift [back] to the state of a commodity, we become detached from mutual responsibility.’ [p. 25] We jump right back into the cash flow. She wonders why we let this happen – why she finds herself ‘harnessed to this economy, in ways large and small, yoked to pervasive extraction…’ [p. 26] And she asks: how can this situation be ‘fixed ’?

Fixing Things

.

At first Kimmerer’s discussion of remedies does not relieve my sense of frustration. ‘Fixing’ this seems a big task, too big for the examples she gives of gift economies we have in our midst today – the free book kiosks and so on. And in the face of that, her language strikes one at times as just a bit cloying. It is too full of words like ‘bellies’ and ‘chortling’ and ‘mouths full of berries’ to be convincing as a narrative standing up to the big boys of monetisation, extraction and commodification.

But, in her defence, Kimmerer spends her days when she is not teaching or writing either out in the woods observing the subtle realities of natural processes, or behind a microscope, observing them even more closely. She writes from direct experience of how plant, animal, insect and fungal communities behave. Her sweet tone is not the result of her having put on rose-coloured glasses. It is more likely that she is simply reporting what she observes. Considered in this way, her argument begins to feel stronger. In any case, readers of her earlier writings such as Gathering Moss and Braiding Sweetgrass will know that she deals very effectively with the far-from-sweet phenomena of severe environmental decline, and as a botanist studies it firsthand with her students in upstate New York.

In Gathering Moss, for instance, she relates the shocking state of Lake Onondaga, one of the most polluted lakes in the landscape of the American northeast. Its now crusted white shores, extending into many acres, are nearly devoid of life. This is the work of companies such as Benson Mines, Allied Chemical, Honeywell, and the Solvay Processing Company, which have been dumping mine tailings, mercury, salt processing residue, ammonia and soda ash into the lake since the 1880s. The lake is near Kimmerer’s home, and some of her students study the consequences of the companies’ neglect, marvelling when a single strand of moss manages to root itself in the hard white mass.

She is not, then, ignoring such states of affairs. She does not expect that The Serviceberry will be enough to inspire the next revolution. Nor does she see the gift economy taking down Big Industry, Big Pharma, Big Chem or any of the other bully boys on our global block.

But then hope arrives from an unexpected quarter. One of her observations is that the current dominant, aggressive economic mode is really rather similar to that of pioneer plants, aka ‘weeds’, when they colonise a patch of bare earth. Bold as brass, they are the first to get in there after some event has left the soil exposed. They root themselves in, fast and hard, shoving out their more delicate relations.

These pioneer species are opportunists, with traits that consume resources, crowd out others, and reproduce like crazy. It’s all ‘me, me, me’, investing only in their own exponential growth with no regard for the future, their relatives, or longevity. Sound familiar? It’s as if Euroamericans, in the age of colonisation and displacement of ‘old-growth cultures’ are behaving like colonizing plants after a massive disturbance, dominating the landscape.

But these colonizing plants find they cannot continue this rate of growth and resource extraction. They start to run out of resources, disease may attack the overdense populations and competition begins to limit their growth. In fact, their behaviour facilitates their own replacement. Their rampant growth captures nutrients and builds the more stable conditions in which their followers can flourish. Incrementally, they start to be replaced. [p. 97 & 99]

I have seen this in my own garden. This is a (scandalously) wild place where plant communities form and reform. Over the last three years or so, a patch of what had seemed to be indomitable ground elder has been slowly but surely diminished by the stately march of a spikey army of yellow Lysimachia. It is taking over. No one thought it would, or could. But it is.

This kind of thing gives Kimmerer a hopeful scenario with which to end the book. After the demise of the aggressive short termers, she explains:

The ones who come next are different, growing more slowly…. Stressful conditions incentivise nurturing relations of cooperation alongside competition. The extractive practices of the colonists must be replaced with reciprocity and replenishment if anyone is to survive. Investing in persistence, the new inhabitants are in it for the long haul. These communities have been called ‘mature’ and ‘sustainable,’ in contrast to the adolescent behaviour of their predecessors. [p. 99–100]

Hopeful Processes

.

What then is needed? How do systems actually change? Kimmerer delves into the detail:

The natural process of ecological replacement highlights two mechanisms at work in replacing a complex system that dominates the landscape and seems too big to change. Succession relies in part on incremental change, the slow, steady replacement of that which does not serve ecological flourishing with new communities. But it also relies on disturbance, on disruption of the status quo in order to let new species emerge and flower.

Some massive disturbances are destructive, and recovery from them may not be possible. Other disturbances, of the right scale and type, create renewal and diversity. Indigenous land stewardship relied on humans using carefully calibrated kinds of disturbance to create a living mosaic in different stages of recovery. Disruptions create gaps, openings and edges between the new and the dominant. I want to see emerging gift economies nurtured in the gaps carved out of the overbearing market economy. [p. 100–101]

It is then, for Kimmerer, the creative identification and re-inhabiting of these gaps that is our task at this juncture. The multiplication of small acts of re-inhabitation can create a network of new ‘edge economies’ to sit alongside and in between the dominant economies, gaining physical, mental and spiritual strength with each new member. The collective, communicative mind expands, edging towards a new viability. I find this profoundly hopeful. And I feel I have my marching orders. Where is the next gap, the next edge? I am on the lookout for it.

The Serviceberry was published in the USA by Scribner and in London by Allen Lane in 2024.

The Serviceberry was published in the USA by Scribner and in London by Allen Lane in 2024.

Illustrations by John Burgoyne, with his kind permission.

Sources (click to open)

[1] Published originally in Emergence Magazine [/].

[2] ROBIN WALL KIMMERER, Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses (Oregon State University Press, 2003).

[3] ROBIN WALL KIMMERER, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants [/] (Milkweed Editions, 2013).

Martha Cass is a student of Ibn ‘Arabi. She is a Trustee of the Muhyiddin Ibn ‘Arabi Society and of the Abbey, Sutton Courtenay, and Head of Campaign at University College Oxford.

The text of this article has a Creative Commons Licence BY-NC-ND 4.0 [/]. We are not able to give permission for reproduction of the illustrations; details of their sources are given in the captions.

More News & Views

Don’t Take It Easy

Richard Gault is inspired by Michael Easter’s book The Comfort Crisis and explores the idea of ‘misogi’ during a 600-mile walk across Scotland

Book Review: ‘Conversations with Dostoevsky’

Andrew Watson engages with an innovative new book by George Pattison which explores Dostoevsky’s relevance in the contemporary world

Thich Nhat Hanh & the Poetry of Engaged Buddhism

Philip Brown presents the poem ‘Recommendation’ and comments on the potential of contemplative art to foster compassion

Introducing… ‘Perfect Days’ and ‘Nowhere Special’

Jane Clark watches two films with a contemplative theme

Book Review: ‘Irreducible: Consciousness, Life, Computers and Human Nature’

Richard Gault reviews a new book by Federico Faggin, one of the leading lights of the science of consciousness

An Irish Atlantic Rainforest

Peter Mabey reviews a new book by Eoghan Daltun which presents an inspiring example of individual action in the face of climate change

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READERS’ COMMENTS

1 Comment

Submit a Comment

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

Very nice & interested book written you. I like Reading. Iam so happy.