arts & literature _|_ Issue 27, 2024

Richard Lewis: Pilgrim in the Land of Children

Robert Hirschfield appreciates the work of a teacher who has devoted his life to inspiring children to write imaginative poetry

Richard Lewis: Pilgrim in the Land of Children

Robert Hirschfield appreciates the work of a teacher who has devoted his life to inspiring children to write imaginative poetry

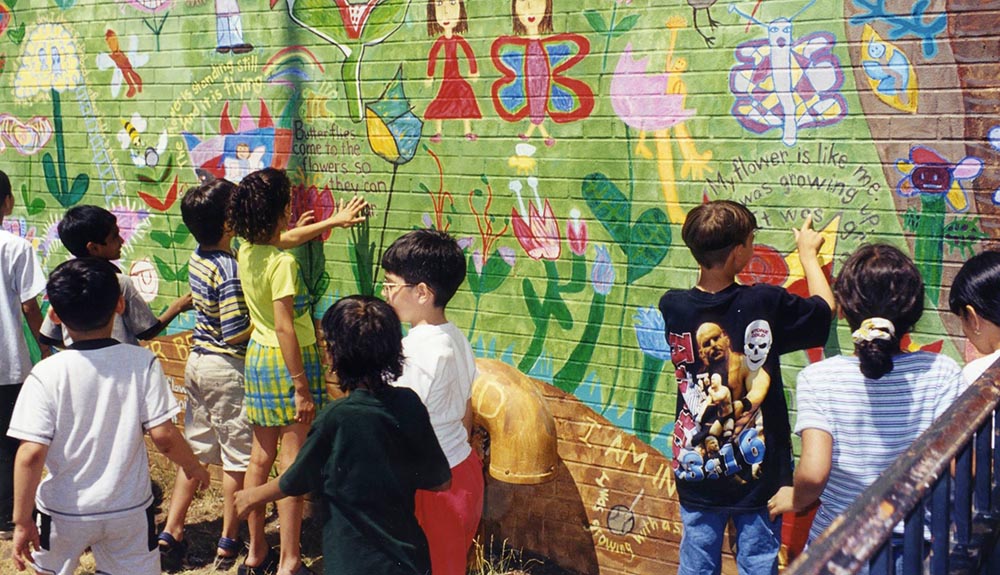

Richard Lewis is a teacher, poet and essayist who as well as producing an impressive body of work himself has spent decades encouraging children’s natural creative, imaginative and artistic abilities. To this end, he founded The Touchstone Center for Children [/] in New York City in 1969 and has run it ever since. Richard brings to his work an attitude of listening and travelling with the children wherever their imagination takes them, providing a space for their unique, individual expression. In this article Robert Hirschfield talks to him about his life and work, and we present some of the extraordinary poetry which children have produced under his guidance.

‘I remember my son when he was two or three years old, standing on top of a large rock and talking to the trees in front of him.’

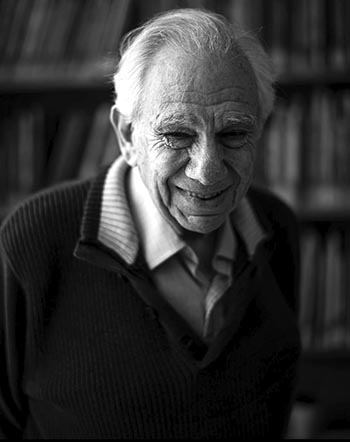

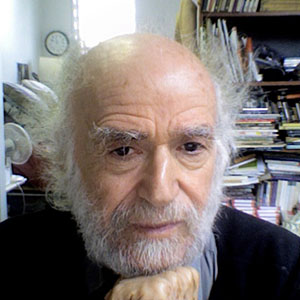

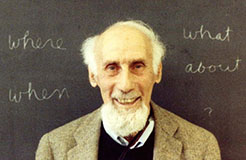

You would probably not notice Richard Lewis if you passed him on the street. The poet/ teacher is old and short. He moves lightly and quietly. He has something of yours you may have lost.

Lewis, 89, carries within him a seed bank. Not of plants to be re-planted in case of future catastrophe, but of imagination. The imagination of children whose poetry he collects, whose genius for living in the moment he tries to emulate. Through his organisation, Touchstone, he’s been teaching poetry to children in New York City schools for the past 54 years.

I first met Lewis at his office in Queens prior to the pandemic. Boxes and folders containing his archives climbed the four walls as if looking for an escape portal. Lewis would sometimes shoot me a bemused, what-have-I created look.

‘I remember my son when he was two or three years old, standing on top of a large rock and talking to the trees in front of him.’

‘I remember my son when he was two or three years old, standing on top of a large rock and talking to the trees in front of him.’

You would probably not notice Richard Lewis if you passed him on the street. The poet/ teacher is old and short. He moves lightly and quietly. He has something of yours you may have lost.

Lewis, 89, carries within him a seed bank. Not of plants to be re-planted in case of future catastrophe, but of imagination. The imagination of children whose poetry he collects, whose genius for living in the moment he tries to emulate. Through his organisation, Touchstone, he’s been teaching poetry to children in New York City schools for the past 54 years.

I first met Lewis at his office in Queens prior to the pandemic. Boxes and folders containing his archives climbed the four walls as if looking for an escape portal. Lewis would sometimes shoot me a bemused, what-have-I created look.

His writings about children have the lightness of sparrows in flight.

A child is the privacy of a universe learning to talk to itself.

These days, Lewis works out of his home on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Meeting up there, we seamlessly continued the conversation we began four years ago.

Children use language differently inside themselves than how they are taught in school. You don’t have to talk to a child about how to skip. There is an interior process, already poetic, to the way they think.

In his book, Taking Flight Standing Still, Lewis illustrates this with a poem written by a five-year-old New Zealand girl:

I hop

The shadow hops too

I lie and think about the sun

And my shadow thinks about me

‘This thinking’ Lewis wrote, ‘is also about play and the child’s ever-shifting playful attention to all the players: the shadow, the sun, my shadow and me. But as frequently happens in play , all the players are directly related to each other with the end result being a profound observation from this child of a universe in which all things are interactively connected.’

But how, the poet is asked, could a five-year-old create a tapestry that flashes both unitive and abstract threads?

‘With guidance’ he says, ‘that child can be any child.’

Lewis’s life as a young man seems incompatible with the child-centred career he eventually embarked on. As a boy, he was drawn to the atonal works of composer Arnold Schoenberg, and later, at Bard, he majored in music composition and philosophy. He also loved the poetry of Blake and Dylan Thomas, became a fine contemplative poet, and wrote books on haiku masters Basho and Issa. In the early 1960s, he found himself doing editorial work at Simon & Schuster, still wrestling with the uncertainty of his next career move.

I felt myself being pushed towards simplicity. I was walking in Central Park one day during my lunch break and had one of those intuitive moments one comes upon sometimes without knowing where it came from or why. I thought to myself, ‘I’ve got to start thinking about children.’ I wouldn’t describe it as a thunderbolt, but a definite yearning. Something was awakened inside me.

His earliest poetry was about childhood, and what he refers to as ’the culture of childhood’, which was to become the main subject of his books.

Smiling a slow smile, he made it clear he didn’t begin as a finished product. ‘I learned that I had to listen. That was the key. If I wanted to be engaged in a conversation with children, I had to listen.’

It is still something he works at, even after all these years and all his diligence and practice. He recalls a snowstorm last spring. He was teaching a class, and his thoughts about the storm were swirling like the wind-driven snow outside.

I found myself talking at length about its magical quality. I had to stop. I didn’t want my sense of magic to overlay theirs. I wanted them to pick up the conversation.

The years of the pandemic separated him from children, which, in a way, separated him from himself. He would often take himself to Central Park and just walk, observing the way the trees lived their seasonal lives of change, flowering and dying and returning to life in the spring, as if nothing calamitous was happening around them.

It brought me, as always, deep into the process of nature’s unfolding.

It brought him respite and a temporary peace. Nature, at least, could be counted on to stay the course, while life was interrupted indefinitely, or ended completely, for two-legged New Yorkers. When everything was more or less back to normal, Lewis got Covid. ‘A mild case,’ he said in a mild voice.

A deep sadness comes over him, a flattening almost, when he speaks of Covid’s effects on children. He points out that beyond their fear of being stricken by the illness, there was the way it snatched from them the very circumstances of life as they knew it.

For the first time, they were deprived of a basic aliveness that was always there. All their social activities were gone. They couldn’t go out and play, or simply talk to one another. Their teachers were teaching from miles away. It was isolating. It all made them fearful of their own childhood, and everything it consisted of.

Like the trees in Central Park, their winter changed eventually into spring. One recent afternoon Lewis noticed children nearby spilling out of school.

He wrote in the journal he’s been keeping for over fifty years: ‘A kind of tumbling joy, as children play as they leave school, inhabiting the dance of their bodies, to leap into the sky of their inward world, and still land, standing up, resting awhile, and starting, all over again.’

Drawing by a child on the Touchstone Forest Project [/]

Children’s Poems

.

In the Beginning

Before there was thunder and lightning, there was just darkness

– it was nothing to see and nothing you could see,

and it would make you feel all alone.

the darkness is a mystery that can’t be solved.

Alicia

Age 11

To be born is to feel like a seed of corn

planted for the first time

David

Age 9

When I was a tree in the dark forest

I saw the beginning of the world.

Then some leaves fell to the ground

And I saw the beginning of the end of the world.

Anon

Age 9

Becoming and Belonging

There is an emotion, the base of all other emotions,

it is an emotion of quietness, without thought

or sound, disturbed only by another emotion

Rick

Age 10

What the flower smells like

It smells new and water like a pond.

It smells quiet and whistles and snaps in cold or wind.

It smells comforting.

Caroline

Age 8

I didn’t know there was another me in the world.

It seems like every time I smell a flower

——————————————I see myself.

Jill

Age 10

The secret of my imagination is that the things

of the universe are things of you.

Charles

Age 8

The star belongs to the sky

————The sky to the angel

The angel to my heart

————My heart to itself

————Myself to poetry

Poetry to something unknown

Anon

Age 11

Homecoming

If you get into a small boat from almost anywhere

you must try your hardest to find some water.

After you have done this you must take off down a channel of thought.

You may make it whatever you suggest. As you begin

to move much faster you forget completely about the boat,

until it’s not there. The wind breathes hard now

and you can see something in the distant beyond.

Now you have reached the shores of your mind

and the sands of the beach are white.

The coral reefs to each side of your head are covered

with many dreams. (You may make of them what you wish.) The path

before you is of a sharp incline but you feel as though

it could be steeper, the pathway is tiring.

After sleeping for a good time, you walk down the path

to the coral, pick a dream, go back to the boat, and

– sleep more, as you float down the channel homeward.

Rick

Age 10

All poems taken from Lewis’s book When Thought was Young (New Rivers Press, 1992).

To explore the life and work of Richard Lewis further…

Watch this video, In the Spirit of Play, compiled by Richard Lewis, designed by Heidi Neilson with photographs by George Hirose, which captures the original writings and art of children as they express the meaning of play.

Video: In the Spirit of Play; Duration 7:51

Read another article about Richard Lewis by Robert Hirschfield (click here [/]).

Find out about Richard Lewis’s recent books published by The Touchstone Center [/] (for the book list click here [/]).

Image Sources (click to open)

Banner: Image courtesy of The Touchstone Center [/].

Inset: Richard Lewis.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] RICHARD LEWIS, Taking Flight, Standing Still: Teaching Toward Poetic and Imaginative Understanding (Codhill Press, Touchstone Center Publications, 2010).

[2] RICHARD LEWS, When Thought was Young (New Rivers Press, 1992).

Robert Hirschfield is a New York-based writer and poet. He has spent much of the last five years writing and assembling poems about his mother’s Alzheimer’s. In 2019, Presa Press published a volume of his poems titled, The Road to Canaan. His work has appeared in Parabola, Tricycle, Spirituality & Health, Sojourners, The Moth (Ireland), Tears in The Fence (UK) and other publications.

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

READERS’ COMMENTS

0 Comments