News & Views

Introducing… Perfect Days and Nowhere Special

Jane Clark watches two films with a contemplative theme

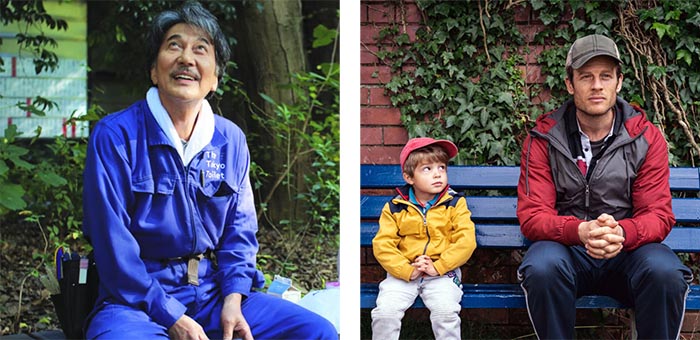

Left: Kogi Yakusho as Hirayama in Perfect Days: Right: Daniel Lamont as Michael and James Norton as John in Nowhere Special. Images; Alamy Stock

Since the time of the romantic poets and the transcendentalists, we have come to associate contemplation and spiritual peace with remote and beautiful settings among mountains, lakes and forests. Think of Wordsworth’s daffodils and Thoreau’s cabin in the woods. It is therefore refreshing to discover these two films which portray lives full of meaning and love in urban environments – and not just glamorous ones but in the crowded, ungentrified areas where the workers live.

Perfect Days (2023, directed by Wim Wenders) is set in Tokyo and follows the daily routine of Hirayama, a cleaner of public toilets, while Nowhere Special (2021, directed by Umberto Pasolini) takes place in an unnamed city in Northern Ireland – shot mostly in Belfast – and tells the story of John, a window cleaner who is the sole carer of his four-year-old son, Michael. The lives of both men are materially modest – they have enough for the basics but there are few luxuries – and they are on the margins of society, often overlooked or ignored by more ‘successful’ people. The power of the films is to show the beauty and richness that they find in the simple tasks which form the rhythm of their days – working, shopping, eating, sleeping – and the level of awareness they display in the way they conduct themselves.

Perfect Days is the more overtly ‘spiritual’ film, widely dubbed as ‘Wim Wenders’ Zen movie’. We watch Hirayama, beautifully played by Koji Yakusho, as he follows the same routine each day and each week, moving around the city for his work and in his leisure time washing at the local bathhouse, reading, eating at a simple café in the shopping precinct, developing his photographs. There is a quality of attention and care in everything that he does. He carries out his work diligently, in contrast to his co-worker who despises it and is constantly on his phone. He keeps himself and his simple apartment scrupulously clean and tidy.

Above all, he notices things. He notices the snatches of nature that penetrate even the most densely populated places – the sky, the trees in the park where he eats his lunch, the small plants he cares for in his apartment – and also the beauty of the city with its lights and extraordinary buildings (Tokyo’s public toilets, we find, are little architectural wonders in themselves). All of this is ravishingly shot by Wenders. Hirayama also notices people, like the homeless guy in the park and a small lost boy, and has time to do a little extra for them. The original Japanese title of the film was Komorebi, which means literally ‘sunshine leaking through trees’ but more generally indicates a connection to nature and the need to pause and appreciate the significance of tiny details.

There are hints as the film goes on of a different kind of past. When Hirayama’s niece comes to stay, having run away from home, his smart cosmopolitan sister collects her in a chauffeur-driven car. ‘Is it true that you are cleaning toilets?’ she asks with tears in her eyes. Thus we learn that he has chosen this life, dropping out of a much more affluent world. ‘There are many worlds,’ he tells his niece, ‘and only some of them overlap.’ It is in conversations with this niece that we get the most explicit expression of Zen principles. ‘Next time is next time. Now is now’, they shout as they cycle along the seafront. The point is made over and over again that Hirayama finds happiness in his life, and his face lights up with a wry and gentle smile as he witnesses the beauty of the world and the vagaries of humankind.

By contrast, Nowhere Special has an overtly tragic theme. John is dying of cancer at the age of 34, and the film, based on a true story, follows his efforts to find the right family to take care of his son when he has gone. Again, the real beauty of the film lies in the depiction of their daily routine as John takes Michael to school, feeds him, combs nits from his hair, reads him stories at bedtime. Their days are punctuated with simple pleasures; a visit to the park, a trip to the supermarket, a birthday cake. As with Hirayama, there are hints of a different kind of past, in this case, a much rougher one. John, we learn, lost his own parents at the age of four and was brought up in care where, he explains to a client who seems to be his only friend, he learnt ‘to never show a moment of weakness’. But now his love for Michael is breaking his heart.

The relationship between father and son is portrayed with enormous tenderness; an almost unrecognisable tattooed and whiskered James Norton gives an unsentimental performance as a good man whose desire to do his best for his son – to give him everything he never had – overrides even concern about his own death. At the centre of the story is the question of values. The visits to potential adopters lay out different versions of what John ‘never had’; is it wealth and the chance for a good education at a private school? Or a ‘normal’ two-parent family? Or siblings? We see John’s own understanding of what is really important mature as his health declines and the moment of decision approaches.

Left: James Norton as John in Nowhere Special. Right: Kogi Yakusho as Hirayama in Perfect Days Images: Alamy Stock

Cleaning and Dreams

.

Both of these are complex films with many layers of meaning. They are not only thoughtful studies of embodied human life but also critical commentaries upon our contemporary Western culture and the values we adopt. There is a great deal that could be said about them. Just to mention two themes which struck me as especially interesting to readers of Beshara Magazine.

The first is the symbol of cleaning and polishing. Both the main protagonists are cleaners who spend their lives burnishing surfaces until they gleam. Images of windows and reflection dominate Nowhere Special; in the opening sequence, for instance, we are presented with a soapy pane wiped clean by John to become transparent, anticipating the process he himself goes through as he reaches clarity not only about the correct path for Michael but also for himself as he becomes reconciled to his death. He takes pride in his work and his window wiper goes into the ‘memory box’ he creates for his son. Likewise, Hirayama spends his time clearing out and polishing to a shine the same toilets over and over again, reminding us of the metaphor widely used in the spiritual traditions of ‘polishing the heart’, a practice which needs to be followed diligently and constantly if the seeker is to maintain clear vision. He too takes great pride in his work, leading a fellow worker to call him ‘weird’.

Secondly: although their focus is upon the mundane, both films intimate that this is not the only world; our life here is shot through with reminders of other dimensions. In Perfect Days, Wenders includes Hirayama’s dreams in his daily routine, images from the day merging and separating, reminding us that we all spend a third of our time in this strange other world. Towards the end, death also enters the picture in the form of a man with terminal cancer. ‘Do shadows get darker when they overlap?’ he asks. On a pavement at the edge of the water they do an experiment to find out and discover, as Hirayama states, that ‘nothing is changing after all. That is all nonsense.’ In Nowhere Special death and what comes after is a constant presence. ‘One day soon your daddy will leave his body”, John explains to Michael toward the end. ‘But I will always be around you, in the air. You won’t see me, but you can talk to me and I will listen. You won’t hear me like you hear me now, but you will hear me inside.’

Perfect Days in particular would reward multiple viewings to catch all its subtle meanings. It is a masterly piece of filmmaking and in my view easily matches Wenders most famous movie Wings of Desire which is also, in a slightly different way, an exploration of embodiment. Both films are superbly executed and acted. James Norton won the British Independent Film Award for Best Actor for his performance and Nowhere Special has a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, while Perfect Days has won multiple awards as well as being nominated for Best International Film at the 2024 Oscars. It is really pleasing to see such deep themes being tackled in films available on mainstream platforms. You can watch them on the following:

Perfect Days on MUBI and Apple TV.

Nowhere Special on Amazon Prime Video and BBC iplayer.

Trailor of Perfect Days

Trailor of Nowhere Special

More News & Views

Don’t Take It Easy

Richard Gault is inspired by Michael Easter’s book The Comfort Crisis and explores the idea of ‘misogi’ during a 600-mile walk across Scotland

Book Review: ‘The Serviceberry’

Martha Cass contemplates the message of a new book by Robin Wall Kimmerer that advocates ‘an economy of gifts and abundance’

Book Review: ‘Conversations with Dostoevsky’

Andrew Watson engages with an innovative new book by George Pattison which explores Dostoevsky’s relevance in the contemporary world

Thich Nhat Hanh & the Poetry of Engaged Buddhism

Philip Brown presents the poem ‘Recommendation’ and comments on the potential of contemplative art to foster compassion

Book Review: ‘Irreducible: Consciousness, Life, Computers and Human Nature’

Richard Gault reviews a new book by Federico Faggin, one of the leading lights of the science of consciousness

An Irish Atlantic Rainforest

Peter Mabey reviews a new book by Eoghan Daltun which presents an inspiring example of individual action in the face of climate change

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READERS’ COMMENTS

1 Comment

Submit a Comment

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

Thank you for the article, it’s very interesting. It seems that the two films reflect lives full of meaning and contemplation in simple places, which makes us reassess our daily lives.