Metaphysics & Spirituality _|_ Issue 4, 2017

The Engaged Contemplative Spirituality of Thomas Merton

Jim Griffin surveys the life and work of the great 20th century visionary who pioneered a new understanding of Christian meditation and interfaith dialogue

The Engaged Contemplative Spirituality of Thomas Merton

Jim Griffin surveys the life and work of the great 20th century visionary who pioneered a new understanding of Christian meditation and interfaith dialogue

A monk who spent most of his adult life at the Cistercian Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky, Merton was one of the most influential figures of the 20th century. His books (The Seven Storey Mountain and Seeds of Contemplation) pioneered the revival of contemplative prayer within the Christian tradition and continue to inspire today. In his later life, he pioneered an equally radical approach to interfaith relations, forming deep connections with religious leaders such as the Dalai Lama, Thich Nhat Hanh, D.T. Suzuki and Martin Luther King. In this article, Jim Griffin indicates that at the heart of his vision was the mystical understanding of silence and the idea of ‘no self’.

When Thomas Merton entered the Cistercian monastery of Our Lady of Gethsemani in Kentucky, on December 10th 1941, he passed by a sign declaring ‘God Alone’. It was indeed on God alone that the young Merton was focused. And like all those entering a monastery within the larger Benedictine family, the aspiring monk came “in order to find God”. Behind the conventional formula, though, lay the deeper truth that the one coming to find God had already himself been found by God. Merton’s journey to the monastery was a response to a call already heard, to an invitation already acknowledged as given. He knew that in the depths of his being his life had already been turned around. The dissolute young student at Cambridge had, in returning to the States and enrolling at Columbia University, found himself drawn first of all to become a Catholic, then to pursue the thought of becoming a Franciscan priest, before finally feeling impelled, against all expectations, to live the silent life of a Cistercian monk. In becoming a monk he lived to the full the monastic archetype described by Raimon Panikkar:

When Thomas Merton entered the Cistercian monastery of Our Lady of Gethsemani in Kentucky, on December 10th 1941, he passed by a sign declaring ‘God Alone’. It was indeed on God alone that the young Merton was focused. And like all those entering a monastery within the larger Benedictine family, the aspiring monk came “in order to find God”. Behind the conventional formula, though, lay the deeper truth that the one coming to find God had already himself been found by God. Merton’s journey to the monastery was a response to a call already heard, to an invitation already acknowledged as given. He knew that in the depths of his being his life had already been turned around. The dissolute young student at Cambridge had, in returning to the States and enrolling at Columbia University, found himself drawn first of all to become a Catholic, then to pursue the thought of becoming a Franciscan priest, before finally feeling impelled, against all expectations, to live the silent life of a Cistercian monk. In becoming a monk he lived to the full the monastic archetype described by Raimon Panikkar:

There lies within every human heart the monastic archetype that could be defined as being a focus on the “one thing that is needful”.

Merton lived more than half his life at Gethsemani. The monastery was the ground and enclosure of his spiritual being. In this respect it was like a mother to him. It is no accident that all Cistercian monasteries are dedicated to Our Lady, the Divine Mother; they are places for the birth of the Divine in human form. For Merton, who lost his own mother when he was six and his father a few years later, the monastery may have provided the solidity, continuity and steady shaping influence that were lacking in his early years. As time went on, he regularly kicked against what he saw as the constraints of monastic life, but he never threw them over, remaining a faithful Cistercian monk until his untimely death on December 10th 1968. Indeed, for all his struggles with his abbot Dom James Fox, Merton was regarded as deeply obedient, the hardest working monk in the monastery, which held and steadied him in the way a loving mother does a fractious child.

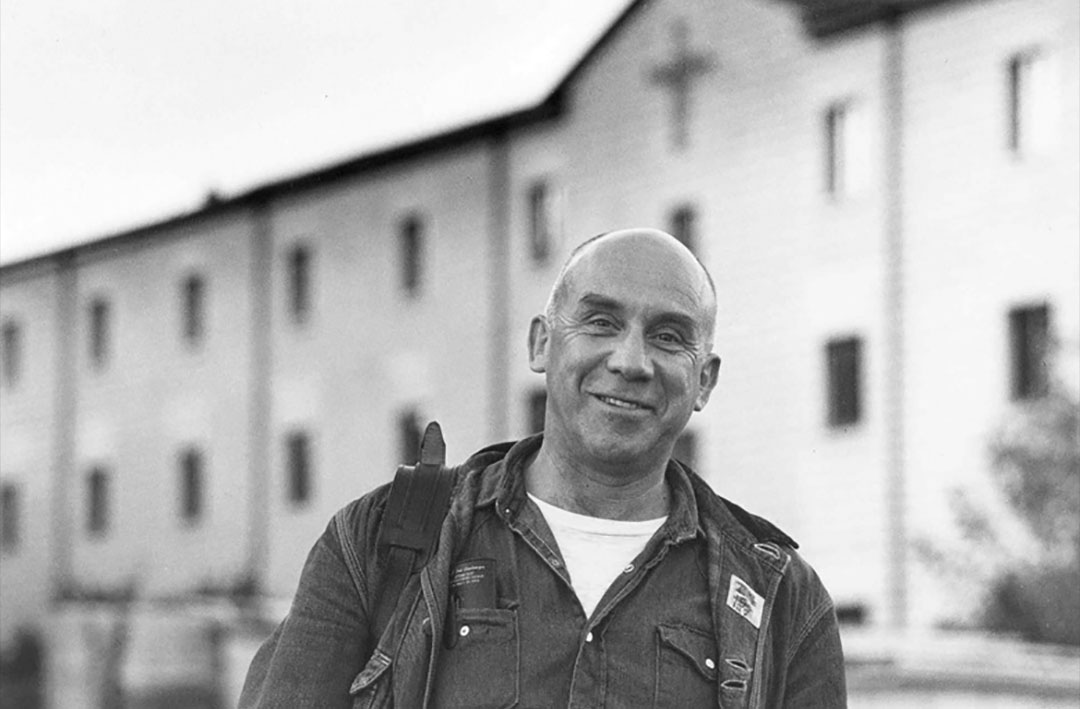

Thomas Merton in Gethsemani Chapel on his ordination day, May 26th 1949. Used with permission of the Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University

Writings

.

Before entering the monastery Merton felt himself called, in large part, to be a writer. He relates that he completed his first novel, or novella, at about the age of 12, and he wrote constantly thereafter – novels, poetry, reviews, diaries. He expected that his writing would finish when he came to Gethsemani, but his first abbot, Dom Frederic Dunne, saw that a continuing role as an author was part of Merton’s monastic vocation. Encouraged by Dunne, Merton wrote his first major work, his autobiography up to the point of his entry to Gethsemani, which was published in America in 1949 under the title The Seven Storey Mountain. It was an extraordinary success, selling over 600,000 copies in the first two or three years, and marked Merton’s arrival as a major spiritual writer. Through his writing and life, through the depth of his spirituality and the engaging ways in which he wrote – on prayer, monastic life, literature, race relations, the peace movement – Merton became the most influential Christian monk of the twentieth century.

Merton’s next major work after The Seven Storey Mountain was the slim volume Seeds of Contemplation, and it is here that he began to explore in depth the great themes of Christian meditation, or contemplative prayer, that would preoccupy him for the rest of his life. While the initial emphasis at this point was on the individual’s attraction to, and immersion in, the Divine Reality, for Merton the mind’s journey into God, as St Bonaventure put it, occurred within the communal setting of shared worship and liturgy. The monks – over 200 of them in Gethsemani in Merton’s early years – rose at 2.00 am to start the day’s cycle of prayer. The progression from Lauds, through Matins, Terce, Sext and None, to Vespers and Compline, rendered the whole day sacred. It also imprinted on the mind and heart of each monk the story of Christian hope and longing – the entire psalter of over 150 psalms was chanted in full every week, and this repetition, combined with the healing and elevating power of Gregorian chant, enabled the reshaping of identity to conformity with Christ, the opening wide of the heart that St Paul speaks of: “We have spoken frankly… our heart is wide open to you… open wide your hearts also” (2 Corinthians 6:13).

Coupled with manual labour in the fields and woods, with study and with private prayer, the monastic life constituted a school of charity, as envisioned by the great medieval Cistercian Bernard of Clairvaux.

In Seeds of Contemplation Merton considers many of the traditional themes of Christian contemplation: moral formation, the stripping away of self-centredness, purity of heart, and the attainment of inward stillness and silence, a movement beyond thought and words to allow a simple openness and receptivity to the Divine Presence. The healing and transforming power of solitude is already central, and is well-expressed in one of his later poems.

Song: If you seek

If you seek a heavenly light

I, Solitude, am your professor!

I go before you into emptiness,

Raise strange suns for your new mornings

Opening the windows

Of your innermost apartments.

When I, loneliness, give my special signal

Follow my silence, follow where I beckon!

Fear not, little beast, little spirit

(Thou word and animal)

I, Solitude, am angel

And have prayed in your name.

Look at the empty, wealthy night

The pilgrim moon!

I am the appointed hour,

The ‘now’ that cuts

Time like a blade.

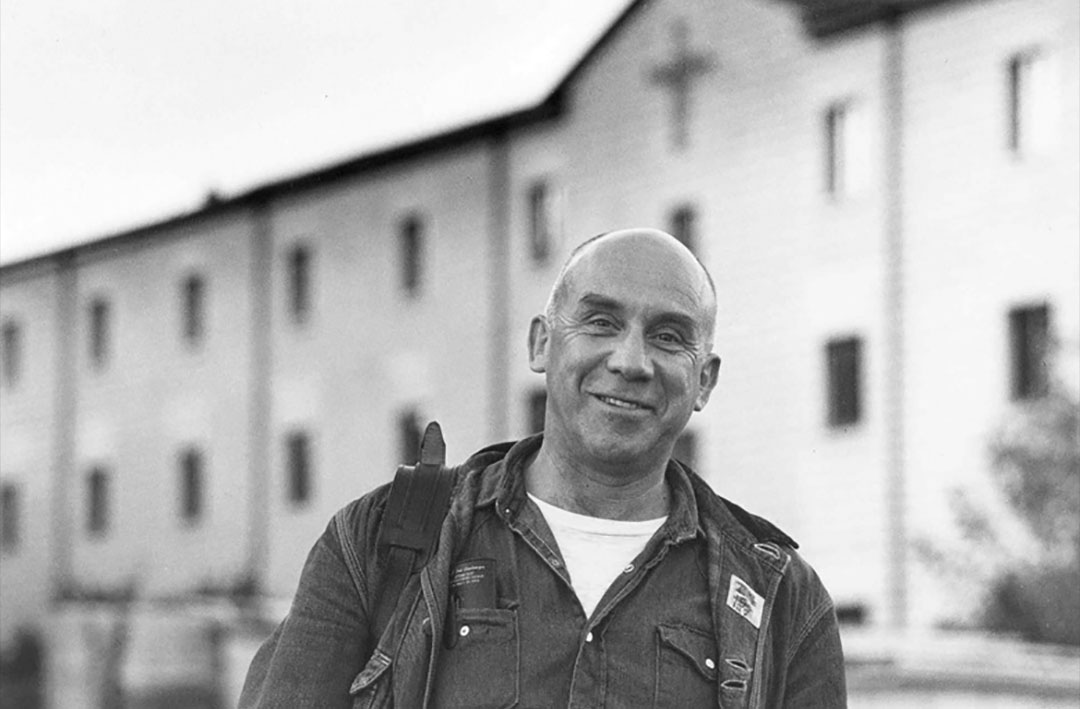

Merton outside the Hermitage in the grounds of Gethsemani Abbey. Used with permission of the Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University

Prayer and Contemplation

.

At the heart of the theology that Merton laid out in Seeds of Contemplation is a contrast between the false self and the true self. Rooted here in the thought of Duns Scotus, the medieval Franciscan whom he studied deeply before entry to Gethsemani, Merton develops the sense that each individual, directly brought into being by God, has a unique personal identity and calling. The task for each person is to live from and manifest that identity, that true self, in the course of a life. Usually, however, it is the opposite that happens: instead of living from our true self, we are drawn to, and live out, versions of our self that are limited, cramped, vain, imperious, fearful – distorted and false representations of who we really are. For Merton, this journey toward and into the true self means that prayer, and the whole spiritual life, is organised around two polar questions: “Who am I?” and “Who is God?”

In all of this Merton is echoing also a view of theologians of the Orthodox church when, following Genesis, they speak of the human person created “in the image and likeness of God”. The image is the deep foundation of our being, our ontological ground in the Divine. Our calling is then to let that image become manifest in who we are, to show forth in all the limitations of our everyday existence the beauty and freedom of the Divine, so that we become in life the very likeness of God. All of this is the fruit of work and grace, of the graced work that is contemplative prayer. Here Merton is solid and clear in his understanding of contemplation, seeing it as a stripping away of all within us that hinders the Divine action, allowing the emergence of an ever-deepening receptivity to God which arises in the stillness of our own urgent longing.

While never turning away from the pattern of monastic life, Merton constantly sought out greater opportunities for prolonged contemplative prayer. From early on in Gethsemani, he criticised the lack of focus on, and opportunity for, contemplation in the monastery. Gethsemani was founded originally on an understanding of Cistercian life that emphasised asceticism, physical hardship, self-abnegation, and a purgatorial way towards God that was actually a deviation from the original Cistercian ideals. Merton spent a great deal of his time researching, writing on and teaching about those ideals. But he did this in a monastery, during the 1940s and early 1950s, that was overflowing with monks and engaged in constant new building projects. In a place of silence there was in fact a great deal of noise, and Merton’s longing for the peace of contemplation drew him to request, at different times, transfers to two more contemplative Orders, the Carthusians and the monks of Camaldoli. Merton’s manoeuvrings to secure a transfer were persistent, at times devious, often comic, and must have sorely taxed Abbot James. But the abbot knew how to manage his monk, and was able to draw Merton back in whenever he became focused on another of his adventures. Despite the lure of greener pastures elsewhere, Merton never left Gethsemani. His wish for greater solitude was, however, recognised and honoured by Dom James, firstly through the provision of opportunities for greater contemplation within the ordinary life of the monastery, and latterly by the building of a hermitage within the grounds, where Merton lived fully for the last three years of his life.

Merton wrote often, at times very poetically, about the value of contemplation, the need for and the fruits of contemplation, but says little in practice about his actual method of contemplative prayer – how he went about it and how he dealt with the various experiences to which it can lead. He does, however, in his correspondence with Abdul Aziz, a Sufi friend living in Pakistan, give a brief indication of his general approach:

I have a very simple way of prayer. It is centered entirely on attention to the presence of God and to His will and His love. […] One might say that this gives my meditation the character described by the Prophet (Muhammed) as “being before God as if you saw Him”. Yet it does not mean imagining anything or conceiving a precise image of God, for to my mind this would be a kind of idolatry.

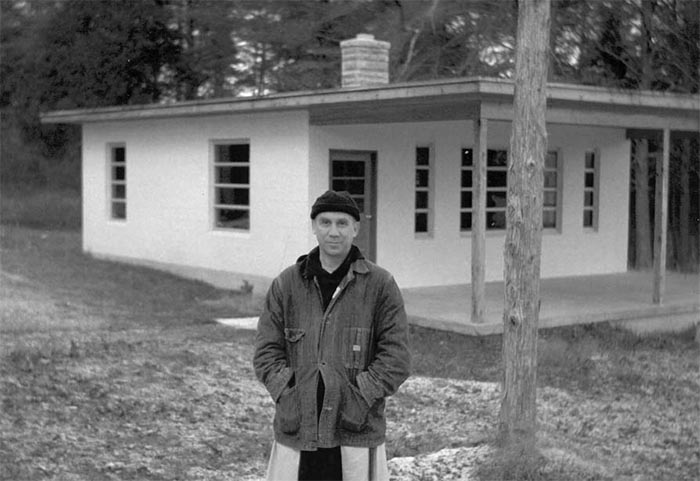

Merton with D.T. Suzuki, New York, June 16–17 1964. Used with permission of the Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University

Love and the Wider World

.

Merton lived this very simple form of prayer in a thoroughgoing way, and could write wonderfully of the sense of the Divine Presence within the natural world, seeing the Divine Light reflected off water and grass, hearing the Divine Word in the calling of the bluejays and cardinals. This simple prayer could also, though, be marked by times of darkness and testing as – like a snake sloughing off its skin – he let drop the lures and aspirations of the false self. In this emergence of Merton, the true man and monk, there are some seminal moments we might consider.

In 1959, away from the monastery for the day, Merton experienced an opening of the mind and heart that left him able to see the world in a radically new way. In Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, he wrote:

In Louisville, at the corner of Fourth and Walnut, in the corner of the shopping district, I was suddenly overwhelmed with the realisation that I loved all these people, that they were mine and I theirs, that we could not be alien to one another even though we were total strangers. It was like waking from a dream of separateness […] if only everybody could realise this. But it cannot be explained. There is no way of telling people that they are all walking around shining like the sun.

Prior to this experience Merton had tended to a negative view of humanity, aware of the failings and sheer destructiveness that mark the human world. That awareness was not eclipsed by this new vision, but became balanced by a sense of the Divine present within the ordinary fabric of human life. Merton had great admiration for the visionary poet Edwin Muir, and in one of Muir’s poems, ‘The Transfiguration’ [/], we find a similar sense of the world unfolded. Speaking with the voice of the disciples who had witnessed the transfiguration of Jesus, with Moses and Elijah, on Mount Tabor, and extending that experience of transfiguration to the whole world, Muir asks:

Was it a vision

Or did we see that day the unseeable

One glory of the everlasting world

Perpetually at work, though never seen

Since Eden locked the gate that’s everywhere

And nowhere? Was the change in us alone,

And the enormous earth still left forlorn,

An exile or a prisoner? Yet the world

We saw that day made this unreal, for all

Was in its place.

The experience of Merton in Louisville was part of a larger process of awakening to the world that shaped his life from the late 1950s through to his death. His writing, particularly his correspondence, was marked now with a new and increasing sense of urgency, and he looked out more from the concerns of the monastery and monastic life to the needs of the larger world. Having achieved fame as a writer, he received an increasing number of visitors and became a guide for many in their concerns and projects. He had a close friendship with Martin Luther King and wrote eloquently on civil rights. With Dan Berrigan and Thich Nhat Hanh he spoke out for peace and against the Vietnam war (his superiors silenced him for a while for being, in their eyes, too outspoken). He developed a deep interest in other faiths, particularly Buddhism, and formed a close friendship with the Zen scholar D.T. Suzuki. He also tapped into the artistic legacy of his parents, producing some fine artwork and calligraphy, and developing a keen eye as a photographer. (Ralph Meatyard, the photographer friend who introduced him to the ways of the camera, described him as a natural photographer. See here [/] for some examples of his work.)

‘Tree in Blossom’ by Thomas Merton. Used with permission of the Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University

Whilst awakening to the world in all its manifest wonder and pain, Merton was also awakening to a need for love, and a capacity for love, that had long lain dormant within him. In a series of remarkable dreams and writings, from the end of the 1950s onwards, Merton came to recognise the wisdom figure Sophia, the Divine creator, mother and guide, as a healing figure long absent from Christian life and thought. The dreams did not simply prefigure his writing, though; they also prefigured the experience of love that came to him in 1965. In hospital for surgery, he was tended by a young nurse usually referred to as M. At 25 she was half his age. They fell passionately in love and Merton, searingly honest as always in his journals, found himself massively torn between his monastic vocation and his love for a woman. In the end his vocation won out, though in a relationship that he seemed to handle with great delicacy and respect, Merton found himself loved and healed, and also able to love, in a way he had never known before.

What we might notice here, though, is not so much this relationship, as the changing sense of the Divine that had grown in him in the previous years. In a remarkable prose poem, Hagia Sophia, in his Asian Journal, he has this to say:

There is in all visible things an invisible fecundity, a dimmed light, a meek namelessness, a hidden wholeness. This mysterious Unity and Integrity is Wisdom, the Mother of all, Natura naturans. There is in all things an inexhaustible sweetness and purity, a silence that is a fount of action and joy. It rises up in wordless gentleness and flows out to me from the unseen roots of all created being, welcoming me tenderly, saluting me with indescribable humility. This is at once my own being, my own nature, and the Gift of my Creator’s Thought and Art within me, speaking as Hagia Sophia, speaking as my sister, Wisdom.

Towards the State of “No Self”

.

Merton’s openness to experiences of this sort, and his capacity to integrate them into his life and grow through the process, was rooted in his contemplative prayer, and in his progressive release from the demands of the false self. His understanding of the self was sharpened, to the point where he was clear – though he had already assimilated this early on in his study of John of the Cross – that any view of the self, any commitment to self, any pursuit of self-interest however refined, constituted a barrier between the person and God, between the human and the divine. The true self turns out in fact to be no-self.

The idea of no-self, though not always expressed in this term, is found at the heart of the Christian via negativa in theology, in apophatic mysticism. Merton was familiar with the whole range of Christian spirituality and mystical literature, particularly St John of the Cross and Meister Eckhart, but as his spiritual journey progressed he felt that something further was needed to help him fulfil his search, something that he could not find within Christian tradition. His immersion in Sufism, and particularly in Buddhism, let him see that there were depths to the entry into the divine life that he had not plumbed. He thought to put himself under the guidance of the perennialist teacher Frithjof Schuon, but that proved impracticable. And as we shall see, he thought also of accepting a Tibetan Buddhist rinpoche as his guru. These thoughts apart, though, the fact is that the progress he had already made had brought him to the edge of breakthrough into the divine life. In 1965, his visitor Sidi Abdesalem, a renowned Sufi teacher, pronounced Merton on the verge of mystical union with God.

In his last year Merton knew himself to be close to some momentous change. His final months were spent on a trip to Asia, ostensibly to give a paper at a monastic conference in Bangkok, but primarily to immerse himself in the streams of Asian spirituality, particularly of Tibetan Buddhism. As he set off on his flight he echoed the words of Zen master, Hakuin, who spoke of the Great Death as the gateway to enlightenment:

We left the ground – I with Christian mantras and a great sense of destiny, of being at last on my true way after years of waiting and wondering and fooling around. May I not come back without having settled the great affair. And found also the great compassion, mahakaruna. […] I am going home, to the home where I have never been in this body.

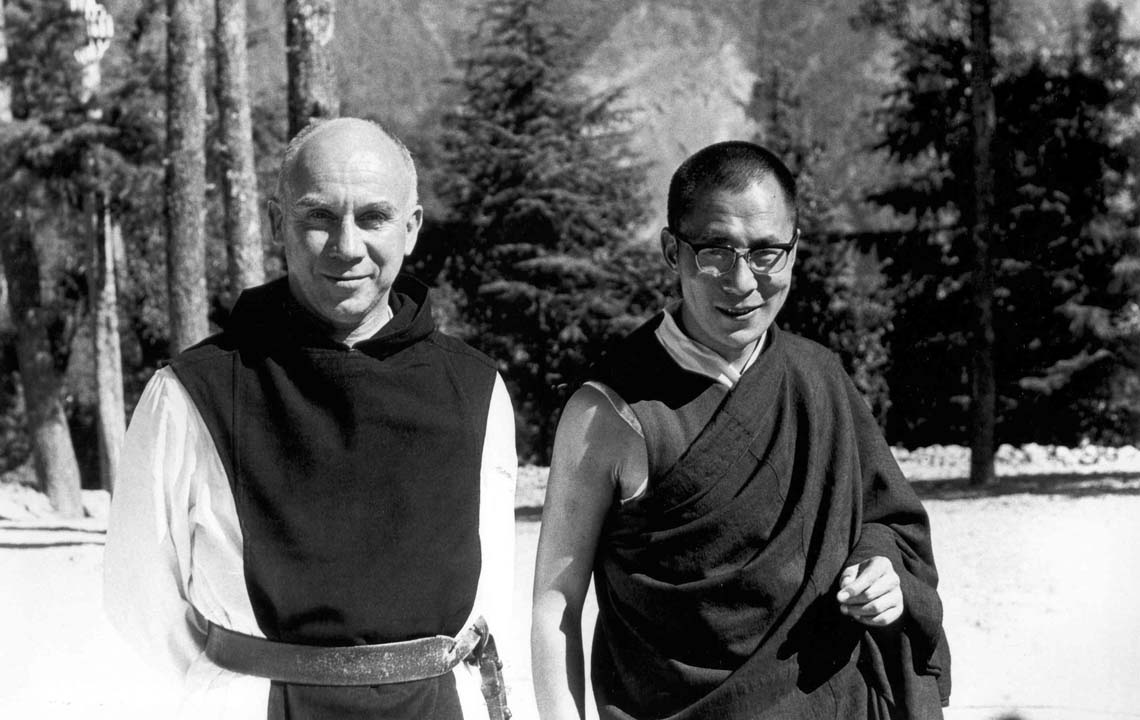

His time in Asia brought him perhaps the experience he was looking for; certainly it gave him the opportunity of meeting, and delighting in the company of, some remarkable individuals. He had three meetings with the Dalai Lama, the third of which involved both men, protocol aside, sitting on the floor whilst the Dalai Lama demonstrated various meditation postures. Throughout his life, Merton had expressed great hesitation about method in prayer and meditation, insisting that prayer simply involved a free and open relationship between the person and God. Latterly, though, he seemed to realise that he needed some method to help him attain the final freedom that he sought, and this is reflected in the conversations he had with a number of Buddhist practitioners. His conversations with the Dalai Lama led to the development of a real affection between the two men, and the Dalai Lama subsequently spoke of Merton as the one who had enabled him to see that there was in fact a real spiritual depth to Christianity.

Merton with Chatral Rinpoche. Used with permission of the Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University

The most important encounter that Merton had, though, was with the man he thought might be his guru, Chatral Rinpoche [/]. Roughly the same age as Merton, Chatral had spent many years in solitary meditation and was recognised as a great spiritual teacher, even if fierce and unpredictable. He died in December 2015 at the age of 102, and is revered by many Buddhists as the greatest bodhisattva of the last two or three centuries. In Chatral, Merton recognised a soulmate, one who had trodden a similar path to his own and was at a similar point of breaking through to something elusive but final. Of one conversation he notes:

The unspoken or half-spoken message of the talk was our complete understanding of each other as people who were somehow on the edge of great realization and knew it and were trying somehow or other to go out and get lost in it – and that it was a grace for us to meet one another.

Merton was deeply encouraged by his time with Chatral. Indeed – his exchanges with the various Buddhist masters he met doubtless helped prepare him for the greatest experience of his journey, a singular moment of awakening. Departing India for Ceylon (Sri Lanka) he went to visit the old Buddhist complex at Polonnaruwa [/]. He was completely entranced by the massive medieval stone carvings of the Buddha and his companions, carvings made, as the Buddhist scholar Walpola Rahula later told him, by the kind of men who don’t exist any more. In Merton’s own words:

I was knocked over with a rush of relief and thankfulness at the obvious clarity of the figures. […] Looking at these figures I was suddenly, almost forcibly, jerked out of the habitual, half-tied vision of things, and an inner clearness, clarity, as if exploding from the rocks themselves, became evident and obvious. […] The thing about all this is that there is no puzzle, no problem, and really no mystery. All problems are resolved and everything is clear, simply because what matters is clear. The rock, all matter, all life is charged with dharmakaya […] everything is emptiness and everything is compassion. I don’t know when in my life I have ever had such a sense of beauty and spiritual validity running together in one aesthetic illumination. Surely […] my Asian pilgrimage has become clear and purified itself. I mean, I know and have seen what I was obscurely looking for.

Some days after his time in Polonnaruwa, Merton was in Bangkok, and on December 10th gave his designated lecture at the conference of monastics. Finishing the lecture, he said “Let’s break and get a coke or something. It’s time for me to disappear.” A few hours later he was found dead in his room, seemingly electrocuted by a floor-standing fan with faulty wiring. It was twenty-seven years to the day since he had entered the monastery at Gethsemani.

Dalai Lama at Merton’s grave at Gethsemani Abbey. Photograph by David Stephenson [/]

Image Sources (click to open)

Banner: Photograph of Thomas Merton by John Lyons. Used with permission of the Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University.

Inset: Church and Bell Tower at Gethsemani Abbey, Louisville, Kentucky, USA. Photograph by Erik Eckel via Wikimedia Commons.

Other Sources (click to open)

For a full account of Merton’s life, see his official biography by MICHAEL MOTT: The Seven Mountains of Thomas Merton, Boston 1984.

RAIMON PANIKKAR in the foreword to PIERRE-FFRANÇOIS DE BETHUNE: Interreligious Hospitality: The Fulfilment of Dialogue, Minnesota: Collegeville, 2010, p. xi.

THOMAS MERTON: The Seven Storey Mountain, London, 1975 edn.

THOMAS MERTON: The Seeds of Contemplation, 1st pub. 1949, New York, 1987.

THOMAS MERTON: Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, London, 1966, p. 153. See also MICHAEL MOTT, pp. 311–12.

THOMAS MERTON: The Asian Journal of Thomas Merton, London, 1973, pp. 4, 143, 233–6.

THOMAS MERTON: The Collected Poems of Thomas Merton, New York 1980:

__ “If You Seek”, p. 340

__ “Hagia Sophia”, p. 363

The letter to Abdul Aziz is in R. BAKER and G. HENRY [eds]: Merton and Sufism: The Untold Story, Louisville, Kentucky, 2005, p.114.

EDWIN MUIR: Collected Poems, London 1960, p. 199.

Jim Griffin is a psychotherapist living in the Scottish Borders. He completed his PhD in Comparative Theology at Edinburgh University, and has taught World Religions and Chinese Philosophy at universities around the world. He has served as a trainer and consultant within the public and voluntary sectors, working in organisational change and in leadership development. Together with his wife Jo, also a psychotherapist, he now spends much of his time as a foster carer to a number of children

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Radical Hospitality: In Memory of Rosemary Haughton (1927–2024)

Phoebe Ryrko remembers her grandmother, an inspiring theologian and activist who saw the divine in everyday life and human relationships

Towards a Deeper Spirituality

The Reverend Peter Dewey looks back on a lifetime working with interfaith projects

Love Will Not Be Idle: Mysticism and Activism

Jane Clark reports on a timely conference put on by the Mystical Theology Network, and talks to its organiser, Dr Louise Nelstrop

Father Bede Griffiths and His New Vision of Reality

Adrian Rance-McGregor reviews the life of a pioneering 20th-century mystic, and the message of one of his most insightful books

READERS’ COMMENTS

What a very beautiful article you submitted on here, dear Jim