Well-Being & Ecology _|_ Issue 24, 2023

Bringing the Land Back to Life

Alan Ereira talks about the wisdom of the Kogi Indians and an important new UNESCO project in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta in Colombia

Bringing the Land Back to Life

Alan Ereira talks about the wisdom of the Kogi Indians and an important new UNESCO project in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta in Colombia

In 1991, in the last edition of the original Beshara Magazine, we published an article by journalist Alan Ereira about an extraordinary people living in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta in the north of Colombia (to read it click here). The descendants of a great civilisation which fled to the hills as the Spanish took over their lands, the Kogi had lived for 400 years in isolation, led by a class of priests called ’the mamas’. They asked Alan to help them make a film in order to communicate with us – ‘the younger brother’ – and warn us about the ecological destruction we are wreaking upon the earth. The result was a BBC documentary and a book entitled ‘The Heart of the World’. Thirty years later, the Kogi are making another attempt to communicate their wisdom, this time through a regeneration project, Munekan Masha, under the auspices of the UNESCO Bridges initiative. Alan talked to Jane Clark and Richard Gault about what it involves and the unified vision which underlies it. At the end of the article we include a video of a recent talk he gave on the project which you might want to watch before reading the interview.

Jane: It is about 30 years since we did an article on the Kogi in the last printed edition of Beshara Magazine and you made your first film about the Kogi for the BBC, From the Heart of the World.[1] So can we begin by doing a little bit of catching up. For instance, since we last spoke you have set up a charitable foundation, the Tairona Heritage Trust [/], which has enabled the Kogi to preserve their culture, and in particular, acquire more land.

Jane: It is about 30 years since we did an article on the Kogi in the last printed edition of Beshara Magazine and you made your first film about the Kogi for the BBC, From the Heart of the World.[1] So can we begin by doing a little bit of catching up. For instance, since we last spoke you have set up a charitable foundation, the Tairona Heritage Trust [/], which has enabled the Kogi to preserve their culture, and in particular, acquire more land.

Alan: Yes, we established the Trust immediately after making the film. Its job was to allow people to channel their expressions of support for the Kogi in a way that the Kogi would know about. We explored various options, and the most practical was the recovery of ancestral land and sites of importance to the Kogi, along with other things attached to it, such as money for health care and administration. But the great thing about land is that it is permanently there, whereas the rest all disappears into the soil as you spend the money.

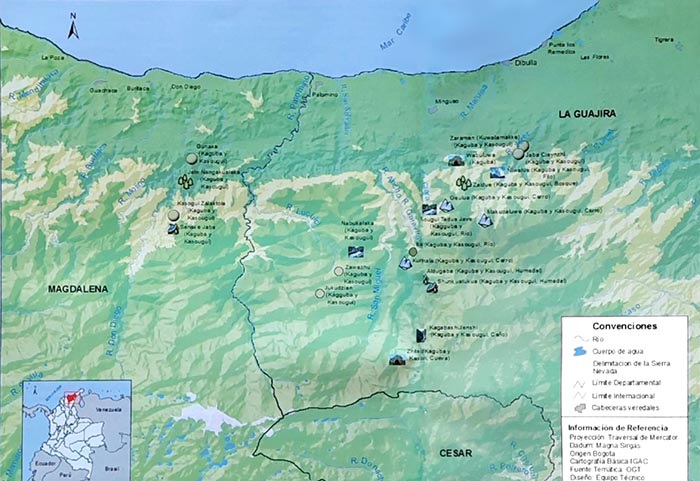

Over the years, lots of people have helped the Kogi acquire further land, including other NGOs and the Columbian government. So the area of territory has greatly expanded. What is more, the new government, which as far as I know is the first socialist government that Colombia has ever had, has just announced a massive expansion of the Tairona National Park, which gives a degree of protection to lands within the area. This includes the traditional territory of the Kogi and the other peoples of the Sierra. But it only gives a degree of protection; it doesn’t actually transfer any ownership to them, although it limits the things that can be done on the land.

Jane: Have there also been changes at a cultural level as the Kogi have made themselves more known to the outside world?

Alan: Obviously, like all cultures, Kogi society has changed over time, and this has particularly been the case over the last twenty years. The government became engaged with the idea of offering support to the indigenous people as part of their general approach to dealing with the violence and civil war and massive illegality, which was particularly prominent in the Sierra. And that has meant offering them a degree of integration into Colombian society which they had not previously had. Not that they necessarily wanted it.

The result is that the government has been instrumental in building a small number of new indigenous towns at the base of the Sierra, some of which are for the Kogi. These incorporate schools where young Kogi are encouraged to learn Spanish. And this has changed the fabric of the society. When we made the first film, hardly anybody spoke Spanish and the Spanish they spoke was rather strange. But now there is more formal education in the language, and there are young people in the indigenous world of the Sierra who are going into further education, including university education – not many of them, it is true, but they exist.

This changes their relationship with their language and their culture. It means that there is a very real risk, as Spanish-speaking Kogi grow up and their ability to access outside political and social power increases, that they will lose interest in the vision of the mamas – and by ‘the mamas’ I meant the spiritual leaders of the community. The mamas are afraid that this might happen. I’ve seen it happen in other societies in the Amazon; it becomes very difficult for traditional leaders to retain the qualities of leadership if they don’t have people subscribing to them.

Jane: You see the language as an essential part of their culture?

Alan: Yes, because personally I think – and there is evidence for this – that once people learn to speak a ‘western’ language, they have also learned a different form of consciousness. They see the world differently. So I consider it very important that there are still mamas who do not speak Spanish and whose understanding of the world is shaped by their traditional language. It is essential to the preservation of what – I suppose we call it knowledge, but it’s not just knowledge; it’s a way of knowing.

The pressure now to integrate the Kogi and the other last remaining peoples who are outside the encompassing blanket of our civilisation is really becoming very acute. It means that the opportunity for cultures like the Kogi to teach us from a separate indigenous perspective may actually be lost within the next 20 years. Therefore, it is very important that we go beyond anything that’s happened before in terms of learning from them.

A Kogi meeting in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia. Photograph: courtesy of The Tairona Heritage Trust

Jane: Before we talk about the specific project you are setting up – the Munekan Masha – can we just to reiterate, for those new to the topic, the importance of the Kogi. My understanding is that this is because they are the only indigenous community left in South America untouched by colonisation – until 30 years ago anyway. So they have managed to retain the original purity of their knowledge in a way that lots of indigenous peoples have not been able to.

Alan: Yes, but I’d even go beyond that. It’s always difficult to argue that people have been completely untouched by the outside world. Of course there have been connections; of course there has been a permeable boundary between the Kogi and what’s around them. What marks out the Kogi, in my view, has been the sustained intellectual campaign by the mamas to understand the difference between our culture and theirs. And to articulate for themselves – and to some extent for us – what it is they think and how they envisage the world around. They have tried to be fully conscious of their own culture, and that is, I think, very unusual. I don’t think we’re particularly good at it. But the Kogi mamas have made it their business through the last several generations to be aware about themselves, their culture and their history in a very clear and well-organised manner.

Jane: I have recently been reading a book called The Dawn of Everything,[2] which brings out a lot of new anthropological and archaeological information about indigenous or pre-colonial societies. It reveals that when the original colonisers first met with indigenous peoples – especially in North America – they found that they had a quite extraordinary level of intellectual development and political and social awareness. And the tribes wanted to engage with the new arrivals in quite a deep level of metaphysical and ethical discussion. All those cultures have now been lost, although some of the conversations are recorded in the journals of the early missionaries, particularly the French.

Alan: Yes. That is how they operated, but most of what these peoples had established as systems of government and agriculture, etc., has been forgotten now. All that’s left are fragments.

Jane: So that is perhaps why the Kogis are so extraordinarily precious to us.

Alan: Yes, and this is understood by other indigenous people in Colombia, who see them as the guardians of other people’s knowledge as well as their own. They regard them as the keepers of the old material and the teachers of it. Years ago, I was invited to a conference of Indigenous Peoples in the Sierra, which was run by the Kogi and another group, the Arhuaco. I travelled to the location where it was being held with other indigenous people, one of whom was a Mayan daykeeper from Costa Rica. He explained to me that every 12 years the Maya send a child to the Sierra to learn from the Kogi. And he had been one of those.

The council of Kogi leaders in 2020 where it was agreed to go ahead with the Munekan Masha Project with UNESCO. Photograph: courtesy of The Tairona Heritage Trust

Response to the Environmental Crisis

.

Jane: The other great change that’s taken place in the last 30 years is that the environmental situation has got much, much worse. The Kogi’s message about the degree of damage that we are doing seemed like a bit of a lone voice at the time, but it is now widely accepted. We can all see what is happening, and that it’s getting worse rather than better. So the Kogi have sent out further messages to ‘the younger brother’, and this new project that you’re involved in – called Munekan Masha – is their current response.

Alan: Yes. The situation is clearly now a critical one. The Kogi have moved to a point now of saying, okay, there are no more secrets. We have to try to fully communicate what we do. And that’s what the Munekan Masha project aims to achieve.

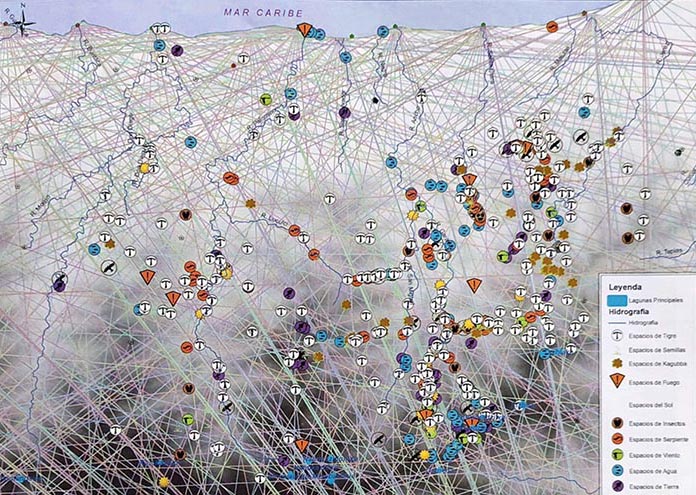

Let me give you some background. About four years ago, a couple of mamas came to me with a book called Shikwakala. This is an ecological analysis of the Sierra Nevada. When I say ‘analysis’, it is because they have tried to put things in terms that we can grasp. This is a deliberately scientific text. It is not about mythology. There’s a certain amount about mythology in it, but what they are doing is showing us that their knowledge is analytic, scientific and precise. It’s just different from ours.

Jane: In your talk you show some of the graphics that they have produced. These show the landscape not as we would see it, but as they see it – as a network of interconnected ‘threads’ and places which I suppose we would call ‘hubs’ where they interact in a particular way.

Alan: Shikwakala is an astonishing work, which they have so far not dared to actually publish. They’re terrified of what we would do with the information, so they’ve only given it to a few friends. And in itself, it is reticent, in that it talks about the need to perform certain activities without explaining how to do them. So it stops at a kind of gateway and doesn’t allow us to do exactly what the Kogis do.

The Munekan Masha project moves beyond that. The idea is to invite a combination of scientists and anthropologists to participate in the regeneration of newly acquired devastated land in a river valley. The aim is to try to get us to understand how to bring the land back to life. The problem, as you saw in the presentation that I made when we launched this through UNESCO Bridges [/] in November, (see video at the end of article) is that the Kogi form of thinking is so alien to ours that it’s very hard to know how science can understand it or react to it or take it on board. Their thinking is fundamentally rooted in what they regard as the certain knowledge that the land itself is a living being of which we are a part. They understand that the only way in which we can successfully work with the land and help it to be sustainable is to participate in this as a shared task where humans and the land work together.

Jane: What do the words ‘munekan masha’ mean?

Alan: They can’t be translated directly; they express that notion that this is the land participating in its own recovery. It’s not rewilding, because it’s not doing it without human beings. But it is land being in a relationship with us and recovering under its own tutelage. So the best I can say is that the name indicates this symbiotic relationship.

This is one of the reasons why the language is so important. You cannot translate things into English or Spanish or our kind of language without changing the fundamental assumptions about the nature of reality that the language contains.

Richard: You talked about their reluctance to publish Shikwakala. This is presumably because they are afraid that we might make bad use of it.

Alan: Yes, the fear is that we are the thieves of the world and they’re terrified of our forms of behaviour. Our main interest as far as they can see is to take whatever we can lay our hands on and convert it into money. Money itself is, of course, a completely meaningless and empty concept. So what we’re doing is simply destroying things.

You see this now in the Sierra, where the cocaine business has been replaced in its economic importance by illegal gold mining, which now is considerably larger in terms of profitability. Both the cocaine trade and illegal gold mining poison the land where they take place, producing a scale of devastation that we are magnificent at creating. One of the fears, I think, about that book is that it maps all the vital sites that are required to take care of the world, and they’re very reluctant to actually make those public because they are also the places where illegal mining will be most profitable.

Jane: Because presumably it will list places where gold is.

Alan: Yes. For my first 15 years or so of involvement with the Kogi, their descriptions of what they regarded as important sites were false descriptions. They would keep using the word ‘sacred place’. It was a word I never understood, but actually, it turns out that they never understood it either! The point about the word ‘sacred’, as far as they were concerned, was it had a meaning to us and that meaning was ‘don’t touch it’. So they called important spots ‘sacred places’.

And indeed, there is a sense that these spots are like abandoned nuclear piles. They are dangerous, but not in ways that they can communicate. More lately, they have begun using the word ‘esuama’, which has more meaning. It means a ‘key place’ where the threads that run through the land connect to other key places. So it’s a hub in a network of an invisible – or maybe partly visible – web of life. Each esuama connects to different places and has different meanings. The word itself is made of two phonemes which mean hot and one. So you could translate it as ‘hot and unique’.

It’s a word that they use to describe a place where things are organised. They will use it when they’re talking about the office of the prime minister, for example. His office is an esuama because it’s a place where things happen; it’s a source of law, and a place of knowledge. And as for the esuamas themselves – they talk about them as being their universities. They speak of them as the source of laws that control life. Above all, though, the network of esuamas are places where they work. It’s as though they are performing a form of acupuncture. They do a piece of work at an esuama but the effect is not there; it is miles away, so it is necessary to know the entire pattern of connections. Now they’ve begun to talk about all this, but they’re still terrified of what we might do if we actually knew where all the esuamas are.

Jane: So in the Munekan Masha project, when they’re going to be talking to scientists and ecologists, is this because they feeling safer because it’s a select group?

Alan: Yes, and also because it’s under the auspices of UNESCO. Right at the start of the whole project, when UNESCO expressed an interest and I told them that, they said, Well, you must tell them to come here. They must come to us, we must see them and we must decide about them and they must listen to us. And so that’s what UNESCO did, which was quite an interesting exercise.

Bringing the Land Back to Life

.

Richard: So the opening up of the Kogis over the last 15 years maybe is partly explained by the fact they see the urgency of the problem. They are thinking; we’re taking a risk here. But if we don’t take this risk, there really is no hope.

Alan: Absolutely. And they refuse to say it’s too late. They do not see a tipping point as having been passed, But we have to find a way to actually learn to do curating of the land. If we don’t, we are totally done for. As I’ve been repeating over and over again recently, only 5% of the land on earth is in the possession of indigenous people. But 80% of all species are now only found on that land. We’ve killed the rest. Without wanting to. Without understanding what we’re doing. Without necessarily deliberately killing them. We just have no idea how to look after things.

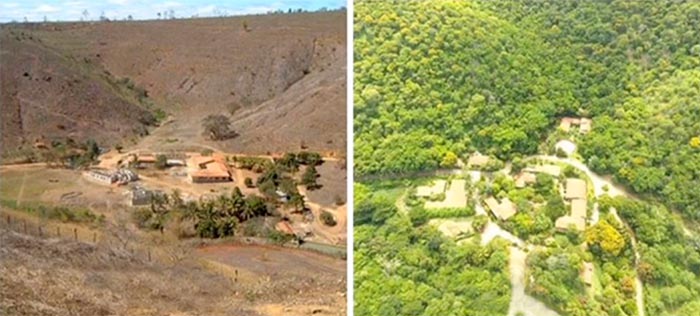

Jane: I think one of the things that’s very striking, which you show in your talk, is the extraordinary success of the Kogi’s recent projects. That in itself must be a validation of the knowledge that they have. For instance, you show what’s happened in 20 years in the Guachaca River valley which was completely devasted by intensive farming and cocaine production; both the forests and water systems have regenerated now and are thriving. You compare this to many other reforestation projects around the world which fail because people don’t understand the whole picture – how to ‘bring the land back to life’, as you put it.

Alan: Actually, I only show a tiny bit of what’s happened. A lot of other things have happened as well. But while what was done in the Guachaca – which I was involved with personally – is impressive and extraordinary and underpins the project we’re doing now, what we learned from it is also not scientifically validated. And therefore there is nothing to talk about in scientific papers or in ecological planning. That’s what’s going to be different about this one.

Jane: So the idea is to repeat that kind of extraordinary regeneration, but to have it properly monitored.

Alan: Yes, the land is in the process of being acquired now. There will be baseline studies done both by our team and by the Kogi who will describe as accurately as they can what is there. The descriptions will be fundamentally different, obviously, because we’re looking at different things. And then we will see how the land changes and develops over initially a three-year period. At the end of three years, we should have enough information to say there is something happening here, and we need to continue.

Jane: You describe in the talk the unique way in which the Kogi go about their projects. When they embark on the task of, say, reforestation, they start at the level of consciousness. First they make contact or refer to the level of what they call the Aluna, which is level of pure consciousness and, when that is done, they develop the project at the level of ideas. So the first thing that they do is work at the imaginative level – imagination not as in the modern conception, but in the traditional sense as someone like Ibn ‘Arabi understands it, as a realm of being, or of intelligibility.

Then after envisaging the whole project at this imaginative level, they prepare the ground through the ritual of planting the crystalline beads – the tumas – that you show in the film, and then and only then will they plant actual seeds. This is all really interesting. But how are you going to do it in a scientific way?

Alan: We won’t do it in a scientific way. They will do it and we will see what they do. The idea of replicating it elsewhere by other people would be a further stage. So what we have not tried to do is to say, okay, we’re going to set up a mirror of what the Kogi mamas do in, say, Nebraska and do the same exercise there and see whether people who are not Kogi can do it. That would be an interesting exercise but I don’t think we would find scientists who were willing to play ball with that at this stage.

Richard: So this is primarily a project of observation and measurement?

Alan: That’s right, and there’s a great deal of interest in doing it.

Finding a Framework for Understanding

.

Richard: If the project succeeds in regenerating the land, as you would anticipate it will, the danger is that the scientists would themselves not be any wiser as to why it succeeded even if they have witnessed it. They wouldn’t be able to offer a scientific explanation of what has happened.

One of the main points that you make in the film is that we are faced in the Munekan Masha project with the problem of talking across what Thomas Kuhn called ‘paradigms’. There is a major difference between the way the Kogi see and understand the world, and the conventional ways of understanding in the Western world. And they come down to questions of ontology. And the ontology of the Western world and the ontology of the Kogis are radically different.

Alan: Yes, I agree that how this all works is something that we don’t at the moment have much of an intellectual framework for. My own analogy is that we’re in the situation we were in about two hundred years ago when Faraday was saying that electromagnetism operates as a field over distance invisibly, and that things like electrical currents in one place actually have an effect somewhere else. The rest of the scientific world regarded that as fantastical, mystical nonsense because they didn’t have a theoretical framework that allowed for electromagnetic radiation.

So the Kogi talk about effects at a distance and we have no idea how to talk about that. But actually we have the same problem with a great deal of modern physics. ‘Spooky action at a distance’ is what quantum mechanics is all about. And now we’re building quantum computers where it’s very, very difficult to talk about what is happening, even though they’re beginning to work.

Jane: I think that as far as ‘spooky action at a distance’ is concerned: we might not understand exactly what’s going on at the level of reality, but there is a wide acceptance now amongst physicists that these strange things really happen and therefore require explanation. And people like Federico Faggin (see our interview) and the heirs of David Bohm (see our article) are developing theories which incorporate the idea that what we see at the physical level is just the appearance of things that are happening at a non-material – or perhaps one would say ‘less-material’, more subtle – level. So there are some potential frameworks emerging now within the context of quantum mechanics at least.

Alan: Yes, I agree that we might be on the edge of being able to talk about such things. There is also another important change in scientific thinking, which is the understanding that is growing very rapidly that the world of plants does not consist of separate individual beings. Rather, there is a very, very densely interconnected and communicating living structure – which is what, of course, the Sierra is. These connections, which are beginning to be read, understood and mapped, are not even just connections through roots. They happen through fungi, through filaments operating in the soil, which bring everything together in one unity. That it is now understood and talked about and published – how something done to a tree in one place will affect other growing things in other places. This makes it a lot easier, I think, to integrate the notion that what people do is something that the plants know about. (See our interview with Merlin Sheldrake for more on this.)

The Importance of Listening

.

Richard: It seems to me that the Kogi understanding is that there is just basically one world. That we, the plants, the animals, and for that matter the stars and everything else, are just all part of a single movement which has arisen from Aluna, which itself is, of course, in a sense, one mysterious reality.

Alan: And that world is not a physical world.

Richard: Yes, indeed. So once you understand this or are able to accept this idea, it becomes obvious that if you see a palm tree here and a tree 1000 miles away or ten miles away, they are connected. And this is not only the case with trees; the same principle applies to humans, and to the rivers and animals. Everything that appears within this world is necessarily interconnected with everything else. As the Kogis say, it is like a body. If you harm one part of your body, you’re going to harm the whole body.

Alan: When you accept that, you’re confronted with the next problem, which is that this is a system of infinite complexity. And in a system of infinite complexity, how do we judge? How to interfere with it, because how can we know where our action leads us? And yet interfering with it is essential if we’re going to take care of it. And that is where the other part of knowledge comes in, which is also going to be very, very difficult for our scientists, which is the process of communication which we describe as divination.

That is another big hurdle that we need to think about and try to explore. The Kogi, as we saw in the film, use bubbles in water as a tool for divination and they become bewildered and enraged with me because I cannot understand what the bubbles are saying. To them it’s so obvious, and to us it’s not. And somehow we have to find a way of speaking about that and learning about it.

Richard: I’m very struck by the emphasis they put on listening. They say; you must think. But to think is to listen. So if they want to know what to do, well, they can consult the bubbles. But I guess they also can simply listen.

Alan: Yes, the bubbles are only one option. Of course, there is a whole world of things that one can listen to.

Richard: Would I be right in thinking that the reason that the training of the Kogis takes place in the dark is that in the dark, the sense that you will have to use and exploit and refine is that of listening. You won’t be distracted so much by vision.

Alan: That is right. It’s one of the biggest problems we have in understanding things, I think is, is that we inhabit a hallucinated world. By which I mean that out of the information we receive from our senses, we construct an apparently solid vision of a reality that we move through walking, swimming, playing. But that reality is itself a hallucination informed by what’s really there hitting our senses in various ways. So, for example, there are no such things as colours except in our heads. They don’t exist anywhere else. The information that provides knowledge of colours does, but the colours themselves aren’t there. So our picture of the world is hallucinatory in that sense.

One of the functions of bringing up a small number of children in the darkness is that they are unable to construct that hallucinatory vision. So when they finally step out into it, they have to do a little bit of work to make any sense of all the stuff that’s hitting them.

Jane: One of the most astonishing things in the video of your recent talk is the interaction between the Kogi ambassador, Shibulata, and Richard Ellis [/], who was at that time Professor of Astrophysics at University College London. Ellis shows him a picture taken by the Hubble Telescope, and says: “Look what we human beings can do with our technology? This telescope can see way beyond the level of sight of anything that a human being can see”. And Shibulata immediately names the only star in the picture.

Alan: He recognises the star. That’s the thing. He can tell the difference between stars and galaxies.

Richard: He then names it, which means that it was already familiar to him. And you explain later in the talk that they can do this because their vision is at a level of ideas, which is pre-matter.

Alan: Yes, for them in fact astronomy is something internal, not external.

Jane: So this is clearly one of the major stumbling blocks to communication between the Kogis and we westerners; we don’t really accept knowing at that level as true knowledge. We always want to have a physical evidence of things because we think that materiality provides true proof.

Alan: Yes, materiality is the problem we have in understanding what they’re talking about. It’s the same when we’re talking about quantum entanglement and so on. The difficulty with understanding any of that is our obsession with materiality.

The Role of the Human Being

.

Richard: If we accept the Kogi’s point of view about the interconnectedness and the unity of the world, then humans must play a vital role in this whole, just as every tree and every fish and every river does. Some people in the western world now believe that the environmental crisis is so severe that it would not surprise them if humanity were to be destroyed. But they think that doesn’t matter, because if humanity is destroyed, well, the earth will still be here and nature will continue. But I think the message of the Kogi is that Aluna definitely needs humankind.

Alan: Yes, in fact, they are quite clear that this is why we’re here; it is the purpose of our existence. In our technological world at the moment, we have two visions where this connection between humanity and the world is denied. One is the Gaia vision in which the world could function without human beings, and the other is the Elon Musk vision in which human beings could function without the world – we could all go and live on Mars and everything would be fine. Both of these are completely opposed to the Kogi’s vision. There is one system; we are part of it and the world is part of us. If you separate us from the world or the world from us, neither can survive.

Jane: So given this, we could say that given that we can’t compute all the possibilities and we have the function of care for the world, there must be a means by which we can do it because we would not be given an impossible task. So this is what the Kogi talk about in terms of the ability to communicate with Aluna through practices such as divination, and also, I assume, contemplation.

Alan: This is why listening is so important. It’s not a question of analysing everything. It’s a question of knowing. It’s going to be very interesting to see how and whether our scientists and anthropologists are able to even describe what’s going when the Kogis embark upon their regeneration programme, don’t you think?

Jane: Can you give us some idea of where the project is now and how it will develop?

Alan: We have now raised enough funds to absolutely commit to the project. We need to see the rest of the funds coming in, of course, as we don’t want the whole project to stumble at some point down the line. But we are in a position to give the Kogi confidence that we’re serious about what we’re doing, which is something that they need. And we need it too to give us the motivation to plough our way through the Colombian legal system, which isn’t easy.

Jane: So when do you start?

Alan: We’re in the process of buying the initial parcel of land. We’re looking at about 50 hectares initially. We also want to buy quite a number of other parcels which are right next door, and gradually expand this up the river valley.

Then the baseline survey will take place in July or August this year. Before that happens, the Kogi mamas will already have begun the contemplative work, which doesn’t have to be done on the land. It has to be done with the land, which is not quite the same thing. And so the mamas will be preparing humanity and the land for the start of the project before the land is actually moved onto. Then one family will become its caretakers; they will live on it to protect it from intrusion, and they will also have to feed themselves off the land, so there is a certain amount of agricultural work that they have to do. From then on, we will be producing new work plans every three months.

Jane: So presumably the more funding you get, the more land you can buy and the more the Kogi can show us. You have pointed out that the mountain in Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta is a kind of microcosm of all the different ecological environments we find in the world; as you ascend, you go through a series of different micro-climates.

Alan: That’s right. Ultimately, we would like to see the project extend up quite high into the Sierra so that we get a sense of the transitions that take place at every level. We’re starting low in an accessible area, and then we’d like to see it extend upwards along the river valley.

The scientists will be visiting periodically and observing, and there will be continuous observation by the anthropologists to record what the Kogi are doing. At the moment we’re working with scientists from Europe, from Zurich, but we’ll also need a local scientist to act as a helper, to go around and report on anything that looks interesting in between the major scientific visits.

Richard: Alan, thank you for talking to us about this very important project. We wish you and the Kogi well with your vital work. We hope to be giving regular updates on your progress in the magazine.

To read the 1991 Beshara Magazine article by Alan,

Message from the Heart of the World, click here.

To see more about the work of the Tairona Heritage Trust, click here [/].

Just as we were preparing this article, the Kogi were in the news for another reason – the return of some of their sacred artefacts by the German government. Click here to read more.

Here is the video of Alan’s talk about the Munekan Masha Project:

Update

.

In 2024, we did a follow-up interview about the Munekan Masha project with the new chairman of the Tairona Heritage Trust, Lucy Attala. Click here…

Image Sources (click to close)

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] The Heart of the World: The Elder Brother’s Warning. To view, click here [/]. See also ALAN EREIRA, The Heart of the World (Jonathan Cape, 1990).

[2] DAVID GRAEBNER and DAVID WENGROW, The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity (Penguin, 2022).

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Cooking in the Ainu Way

Artist Eiko Soga talks about her experience of living with the indigenous people of Japan

Entangled Life

Dr Merlin Sheldrake talks about the remarkable world of fungi, and what they can tell us about ourselves and the interconnectedness of the world

Fighting Fire with Fire

Victor Steffensen talks to Rosemary Rule about his pioneering work reintroducing indigenous cultural burning practices in Australia

Paddling the Magic Canoe: The Wisdom of Wa’xaid

Briony Penn talks about her relationship with the native elder Cecil Paul – Wa’xaid – and their successful campaign to preserve the glorious Kitlope River area in British Columbia

READERS’ COMMENTS

Contemplative concentration—“listening”, imparts knowledge first to the heart (spiritual), then and only then to the head (physical/material). Yes, it’s all one, but the order, the process, makes all the difference. }:- a.m.

Thank you

“We are here to witness the creation and to abet it. We are here to notice each thing so each thing gets noticed. Together we notice not only each mountain shadow and each stone on the beach, but, especially, we notice the beautiful faces and complex natures of each other. We are here to bring to consciousness the beauty and power that are around us and to praise the people who are here with us. We witness our generation and our times. We watch the weather. Otherwise, Creation would be playing to an empty house”

Annie Dillard – American author

“If you want to awaken all of humanity, then awaken all of yourself. If you want to eliminate the suffering in the world, then eliminate all that is dark and negative in yourself. Truly, the greatest gift you have to give is that of your own self-transformation”

Lao Tzu

“The only thing separating you from me is your idea of me”

Mina Lee

“A man must first of all understand certain things. He has thousands of false ideas and false conceptions, chiefly about himself, and he must get rid of some of them before beginning to acquire anything new. Otherwise the new will be built on a wrong foundation and the result will be worse than before. To speak the truth is the most difficult thing in the world; one must study a great deal and for a long time in order to speak the truth. The wish alone is not enough. To speak the truth one must know what the truth is and what a lie is, and first of all in oneself. And this, nobody wants to know”

George Gurdjieff – c. 1872 – 1949 – Russian philosopher, mystic, spiritual teacher, composer

“The issues the world faces, the destruction, greed, genocide, economic meltdown, etc… cannot and won’t be resolved until man faces himself, looks at himself and does the work to gain Self Knowledge, beyond worship of the personality and ego. Humanity is deeply conditioned through Culture, Society, Religion, Media, Nationalism, Education, Government, our upbringing, and all kinds of illusionary Beliefs. Before we can offer any solutions we need to become aware of this conditioning and do the work necessary to truly understand ourselves, our mechanical reactive behaviours, emotional addictions, our biases to take in certain information but automatically reject information that conflicts with our (conditioned) belief system”

Dr. Bernhard Guenther – Philosopher

Thank you.

Truth exists, our task is to recognize it and let it guide our actions, our lives. But it requires first listening, and not so much with brain initially, but with the “heart” which then informs the mind. In silence and solitude we listen for as long as it takes to hear an answer, or a question.

RE: “Alan: … 80% of all species are now only found on that land. We’ve killed the rest. Without wanting to. Without understanding what we’re doing. Without necessarily deliberately killing them. We just have no idea how to look after things.”

That’s false. We DO know and we DO “understanding what we’re doing” but modern humans simply don’t care about the reality of what they’re doing because they have a deadly diseased called “Soullessness Spectrum Disorder” …. https://www.rolf-hefti.com/covid-19-coronavirus.html

“Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.” — Martin Luther King, Jr, 1929-1968, Civil rights activist

In Alan’s Ereira ‘s film, the Kogis stresses that they want their message reaches everyone in the world. How would you do to make this happen? This is a challenging task (close to impossible). Reading too much gives me headaches. Just by listening to Alan’s voice and other’s, it eases my mind, although I do not fully understand the whole clip. I think this is the reason why the Kogi do not use letters in their culture. In my childhood, I often saw bubbles with the rain. Now I do not see many of them with the rain. In the view of the Kogi, this a message from Nature. In Europe you have snow. I have just read from the news, there is no snow in Canada this winter. Is this the fatal message that Nature sends us?

Thanks to Alan and all his counterparts. You are doing a wonderful work.

I have a query. Do the Kogi people have a diet without meat and fish?

My query is important. Please forward this query to Alan Ereira.

Thanks

Dear Alan,

Aluna exists everywhere in the world. For example, in your country, Aluna is the seasons, the cloud, the sea, the beach, the forest, the sand, the stone, the birds, the animals..Now with climate changes, its is hard to grasp the original Aluna to our mind. Due to the primitive forests, the Kogi people can see the Aluna with it original existence. Every country in the world now faces the impacts of climate changes, although the impacts may be different in each country. We must clean our mind to grasp the Aluna. Primitive existences may help us to grasp the original Aluna.

Thank you, Alan,

Pham Duc Sinh

The Kogi ‘s population is about twenty thousand people, and they have many Mamas to guide the people. Our societies concentrate the power to a few people. This leads to maniac of the leaders of nations. Just think about this.