A Thing of Beauty… _|_ Issue 23, 2023

A THING OF BEAUTY…

Robin Thomson appreciates the music of Bach and an inspiring new performance of his St John Passion

A THING OF BEAUTY…

Robin Thomson appreciates the music of Bach and an inspiring new performance of his St John Passion

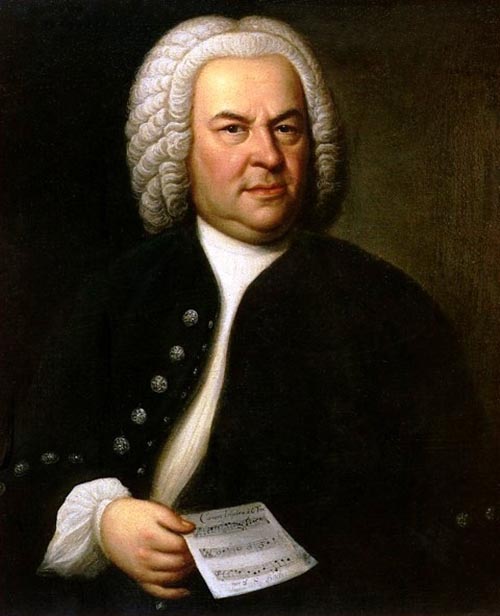

This addition to our occasional series ‘A Thing of Beauty…’ celebrates the glorious music of J. S. Bach, which, three hundred years after its composition, still has the power to speak to modern audiences and inspire them. In fact, it seems to be increasingly doing so. Robin Thomson draws our attention to an ambitious project based in the Netherlands which aims to perform all of Bach’s compositions, and is utilising the power of new technology to make them freely available to everyone via the Internet.

This 2017 performance of the St John Passion was recorded in the Netherlands as part of the ongoing ‘All of Bach’ project. As its title suggests, the idea behind the initiative is to perform every known piece of music written by the German composer Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750). This is a corpus of 1080 pieces written for diverse occasions and a wide range of performers, ranging from solo instruments and chamber groups to orchestral and church music, and from tiny dance movements for practice on the keyboard to complex suites for solo instruments – many of them marathons of intellectual rigour – and the monumental cantatas, passions and masses with which he served his ecclesiastical employers. Since the project began in 2014, some 350 performances have been completed, including the two well-known Easter passions (musical narrations of the Gospel accounts of the Passion of Jesus) of St Matthew and St John.

‘All of Bach’ is the initiative of The Netherlands Bach Society, based in the town of Naarden. The Society was originally founded just over a century ago for the purpose of performing Bach’s St Matthew Passion on Good Friday each year, war and pandemic notwithstanding. Forming part of its centenary celebrations, the project is intended to reach far beyond the local audience, with each performance being professionally recorded and filmed to a high quality in appealing locations across the country, and then made available freely in video form. Alongside the music itself is a wealth of background information such as texts and interviews with the performers.

Appeal Across the Centuries

.

So why this contemporary interest in Bach? How did a provincial Lutheran choirmaster forge such a synthesis of what had gone before that he would shape the trajectory of Western music for the next three centuries? The story has been one of gradual discovery. Following his death in 1750, Bach passed through two centuries of relative obscurity, known mostly only in the German-speaking world for his church music and as a source of technical study for other composers such as Beethoven. Revivals have come and gone; the first well-known figure associated with making Bach more widely known was Felix Mendelssohn, who staged the St Matthew Passion at the age of twenty – albeit heavily cut and with arrangements added of his own – for the great and good of Berlin in 1829.

A century later the Nobel Prize-winning polymath Albert Schweitzer brought Bach’s organ music to public recognition and wrote a lengthy biography [1] in which, as well as examining the different genres of his compositions in some detail, he looked into the composer’s influences and inspirations, the sources of the old German chorales (hymn tunes) and the textual sources he set in his cantatas and passions. In the opening lines of his compendious biography, written in about 1908, Schweitzer attempts to identify the universal quality of Bach’s work:

Some artists are subjective, some objective. The art of the former has its source in their personality; their work is almost independent of the epoch in which they live. A law unto themselves, they place themselves in opposition to their epoch and originate new forms for the expression of their ideas. […]

Bach belongs to the order of objective artists. These are wholly of their time, and work only with the forms and ideas that their time proffers them. They exercise no criticism upon the media of artistic expression that they find lying ready to their hand, and feel no inner compulsion to open out new paths. […]

He goes on to say more about what he means by an ‘objective’ artist:

In [such artists] the artistic personality exists independently of the human, the latter remaining in the background as if it were something almost accidental. Bach’s works would have been the same even if his existence had run quite another course. Did we know more of his life than is now the case and were in full possession of all the letters he had ever written, we should still be no better informed as to the inward sources of his works than we are now.

The art of the objective artist is not impersonal, but super-personal. It is as if he felt only one impulse – to express again what he already finds in existence, but to express it definitively, in unique perfection. It is not he who lives; it is the spirit of the time that lives in him. All the artistic endeavours, desires, creations, aspirations and errors of his own and of previous generations are concentrated and worked out to their conclusion in him.[1, p. 1]

Schweitzer is not alone in his estimation. The cellist Pablo Casals is said to have stumbled on a copy of the solo cello suites as a teenager in a second-hand shop in Barcelona in 1889, and went on to be the first to record them in their entirety at the age of sixty. He said of Bach:

To strip human nature until its divine attributes are made clear, to inform ordinary activities with spiritual fervour, to give wings of eternity to that which is most ephemeral; to make divine things human and human things divine; such is Bach, the greatest and purest moment in music of all time.[2]

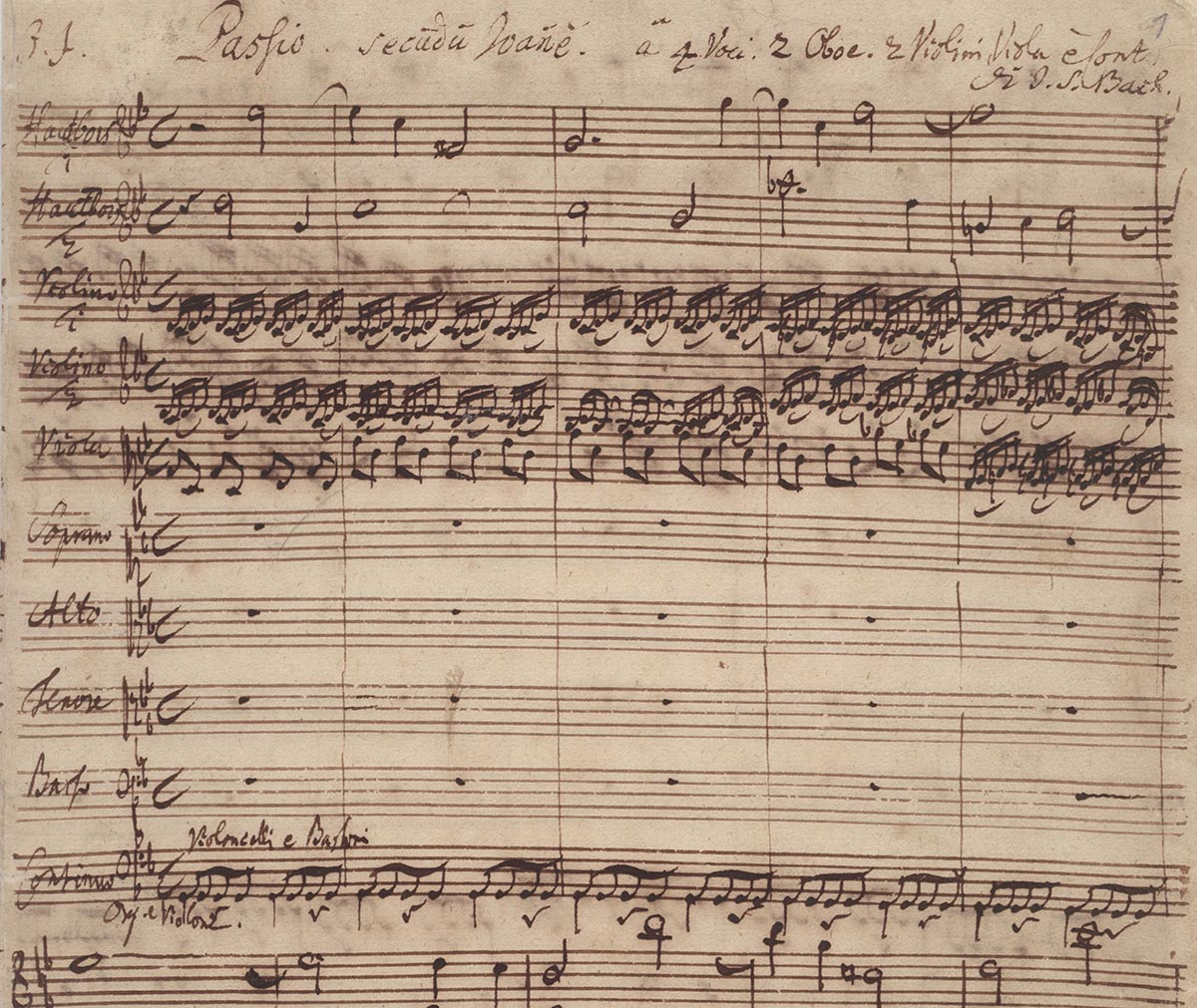

The first page of a surviving autograph manuscript of the St John Passion, dated c.1738. In the top left corner the initials ‘J.J’ are an abbreviation of ‘Jesu juva’– Jesus help me. Manuscript: Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Image: via Wikimedia Commons

Move your computer mouse over the image to enlarge

Danced Religion

.

One of the best overviews of Bach’s life and times is a 2013 BBC documentary by John Eliot Gardiner, a well-known conductor and champion of Bach’s work. Bach: A Passionate Life [3] (see the full video below) tells the story of a boy born into an extended Lutheran family of organists, choirmasters and music teachers, who would yet tread a lonely and often tumultuous path towards finding or forming the conditions he required for his ultimate declared objective – that of creating ‘a well-regulated church music to the glory of God’.

Various theories for Bach’s talent are put forward in the film, from the psychological (the deaths of both parents when he was about nine years old forced him into a survival mode in which he drove himself to outstanding achievement) through to sheer unexplained and inexplicable genius, leaving the viewer to speculate on what many have also described as divine inspiration. There is no doubt that Bach was a deeply religious man and that he saw music as an act of praise. For instance, we know that he began all his manuscripts with the initials ‘J.J.’ – ‘Jesu juva’ – ‘Jesus help me’, as was not uncommon in the Baroque era and earlier. And the end of the manuscript would be inscribed SDG – Soli Deo Gloria – ‘Glory to God alone’. He eschewed the fashionable new genre of opera, considering it superficial, and gave himself to the tougher (and less well-paid) world of church music.

Since the mid-20th century, works by Bach and other composers of the Baroque and earlier periods have come increasingly to be performed in a manner thought to be closer to the style of those times. This ‘period performance’ approach, of which Gardiner is a major exponent, draws on continuing research and an increasing body of performance experience. It sometimes contrasts starkly with Romantic and post-Romantic practices, in which Bach performances could be ponderous and overwrought. Perhaps ideas of an austere religious sect and the stuffy garb of the period – the portly God-bothering Bach in his wig – only added to this sense. But Gardiner came to a very different conclusion. So much about Bach, he tells us, was inspired by dance; indeed, he speaks in the film of Bach’s work as ‘danced religion’.

Mieneke van der Velden plays the viola da gamba during the beautiful aria Es ist vollbracht in the St John Passion (see video 1:20:29). Although this instrument was already outdated by Bach’s time, he used it on occasion to create a particularly evocative sound. Image: from All of Bach video [/]

The evolving genre of period performance, of which the ‘All of Bach’ project is a vivid manifestation, generally involves small numbers of players, period instruments (or replicas) and a generally lighter performance style – more agile, often brisker tempos, often with the players standing up. There is perhaps also an interior orientation, an unspoken intensity of focus which the new performance style has enabled, in which the music and its spirit can be heard more clearly. The result is a robustness and a release, paradoxically, from slavish attempts to copy the rules of ‘period playing’. It is as though by aligning with the historical and stylistic approaches, the musicians reach to the essential and unchanging in the music, which is then not affected by outer detail. There is lightness, cleanness – and ample expressive range.

For Bach in particular, this outcome is of the essence. His compositions have been said by many to be durable and to possess a rare degree of freedom; they can be transcribed, transposed, speeded up, slowed down, arranged for all manner of media without losing their vitality, just as they were frequently adapted and recycled by Bach himself. His music approaches pure form, pure intelligence, in which harmony, melody and counterpoint are all fluent and can manifest themselves in unending permutations with seeming effortlessness. Unlike the work of many other composers, which is concerned with the mortal world, Bach’s work seems to originate in the eternal. Reference is made in Gardiner’s film to Bach’s fascination with numbers and the mathematical logic that extended in some cases even to writing a melodic line upside down or back to front to generate inversions and reflections.

Also notable are the texts used by Bach in his sacred works. He drew on the rich German vernacular tradition, making clear his debt to Martin Luther for his encouragement of artistic expression in divine praise. He also took from mystical sources: two of his best-known cantatas, with words taken from Philipp Nicolai (1556–1698), draw on the Song of Songs, specifically the union of the bride, the soul, with the divine bridegroom. In one of these cantatas, Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme, the mystical union is interwoven with the parable from the gospel of Matthew about the wise virgins who have their lamps prepared, ready for the unannounced arrival of the bridegroom (click here [/] to hear the All of Bach performance of this).

The Grote Kerk, Naarden, where the performance takes place. Consecrated in 1479, this is one of the most iconic churches in the Netherlands. Its unique painted barrel vault shows the passion of Jesus in eleven panels. Photograph: christophe cappelli [/] / Alamy Stock Photo

The St John Passion

.

The sublime union of man and God is referenced again in the St John Passion. Shorter than the better-known St Matthew Passion, and written earlier, the text is not limited to narrating the passion and crucifixion of Jesus. As the conductor Jos van Veldhoven points out in his video discussion of the Netherlands Bach Society performance (see video right or below), a motto is inscribed above Bach’s manuscript score: ‘Not only in heaven but also in adversity, we must praise God’. And as the narrative – which would have been entirely familiar to a regular church-going audience – progresses and Jesus is betrayed, arrested and tried by the Roman governor Pontius Pilate, a thread of consolation recurs uniquely in this work. Amid the baying mob of the trial scene, the space opens suddenly for these two contemplative arias:

Video: Jos van Veldhoven on The St John Passion. Duration: 13:36

Consider, my soul, with anxious delight,

with bitter pleasure and a heart partly oppressed

that your highest good depends on Jesus’ sorrow,

how for you from the thorns that pierce him

heavenly flowers blossom!

You can gather so much sweet fruit from his wormwood

therefore look unceasingly towards him! [See video 46:54]

Ponder well how his back bloodstained

all over

is like the sky –

where after the deluge

from our flood of sins has abated

there appears the most beautiful

rainbow

as a sign of God’s mercy! [See video 49:22] [3]

Appearing as an interior, contemplative sentiment, this gives a larger perspective, more encompassing, than the usual interpretation of the crucifixion story. As van Veldhoven notes, in Bach’s version the killing of Jesus is not what it appears to be; its wider meaning is that through suffering and death the human condition, universally, is brought to its supreme union with God.

This same sentiment appears in a final, ‘extra’, chorale with which the work ends. Here the words of Solomon from the Song of Songs are briefly referenced concerning the ‘small chamber’, the ‘bedroom’ – symbolic of the human heart – in which the bride (the soul) awaits the time when the groom, the Lord, will come and they can finally be together. The work closes as it opened, with the words ‘I will praise Thee evermore!’

Jos van Veldhoven (right), the first musical director of ‘All of Bach’, with Shunske Sato (left) who took over from him in 2018. Sato plays first violin in our recording of the St John Passion. Image: All of Bach

Breathing New Life into Tradition

.

One of the stated aims of the Netherlands Bach Society is ‘to breathe new life into tradition’. As well as their freshly executed performances and imaginative settings, in many concerts they make a point of employing young musicians at the start of their professional lives; the St John Passion recording we feature, for example, is performed mostly by players and singers under 35 years old. Van Veldhoven comments that working with these younger performers brings a new level of commitment and intensity to the performance and is a tonic and restorative for the older players.

Their intention would be recognised by Albert Schweitzer. Later in the introduction to his biography, Schweitzer suggests that Bach was the culmination of a collective creative aspiration that had built up over the centuries, through many other figures, and then at exactly the right time was embodied and activated in a man who was uniquely able to ‘breathe the spirit’ into the musical and textual forms that had accumulated but had yet to be given life, as it were. As different factions of the church in his time argued over whether passions were even permissible, Bach resolved the issue de facto by his magisterial offerings. At the same time, as van Veldhoven has explained (see video right or below), in his use of devices like the leitmotif he was also in some ways ahead of his time, making him a very modern composer.

Video: Van Veldhoven on Bach St John Passion. Duration: 4:12

‘All of Bach’ is by no means the first or only attempt to record Bach’s entire output. In parallel to it is a project currently being undertaken by the J.S. Bach Foundation in Switzerland [/] to perform and record all the vocal works, again with exquisite performances, and other initiatives abound. Of course, large-scale performance or recording projects have existed for decades in the form of concert series or boxed sets of records. As performance practice has evolved, keeping pace with it, it seems, has been a growing collective receptivity to this music and what it can offer us of ourselves. Now, as though waiting for the moment, technology has also kept pace, and the richness of Bach’s works is being opened up to the entire world, for anyone who wants to listen. In this context, productions such as ‘All of Bach’, given unconditionally on the Internet, with sublime performances and superb production values, have the quality of sheer gift.

We have embedded a number of videos into the article to give you a taste of the ‘All of Bach’ performances, but there is an amazing wealth of further material to explore on their website www.bachvereniging.nl

Here is the John Eliot Gardiner film, A Passionate Life (BBC, 2013):

Duration: 1:29:14

Image Sources (click to close)

Banner Image: The Netherlands Bach Society performing the St John Passion at the Grote Kerk, Naarden. Conducted by Jos van Veldhoven. Image: from the video below.

Banner video: All of Bach, St John Passion. Duration: 1:53.12. Also available on the All of Bach website [/].

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] ALBERT SCHWEITZER: J.S. Bach: (German Edition Breitkopf & Härtel, 1908: English translation by Ernest Newman, with author’s alterations and additions, London, 1911).

[2] Casals is reported as saying or writing this at the Prades Bach Festival in 1950. See An Encylopedia of Quotes about Music, compiled by Nat Shapiro (Doubleday, 1978).

[3] English translation by Francis Brown. For the German and full translation, see the All of Bach website.

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

Video: Jos van Veldhoven, Mieneke van der Velden and Angus McPhee on The St John Passion. Duration: 13:36

Video: Jos van Veldhoven on the Leitmotif. Duration: 4:21

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

A Thing of Beauty… ‘Loving Vincent’

Mark Boston reflects on the paintings of Van Gogh, and his experience of working on this remarkable film about the artist’s last years

Mary, Seat of Wisdom and Mercy

Jane Carol explores the vision of the Virgin Mary embodied in the structure and glass of Chartres Cathedral

A Thing of Beauty… The Book of Kells

James Harpur ‘takes a line for a walk’ as he remembers the challenges of writing his poem ‘Kells’

A Thing of Beauty… The Audley Chantry Windows, Hereford Cathedral

Hilary Davies contemplates the work of stained-glass artist Thomas Denny which gloriously expresses the vision of the 17th-century poet Thomas Traherne

READERS’ COMMENTS

Iain McGilchrist cites with approval the philosopher Emil Cioran: “In an interview in Newsweek in December 1989 Cioran asserted that ‘without Bach, God would be a completely second-rate figure’, and that ‘Bach’s music is the only argument proving the creation of the Universe cannot be regarded as a complete failure’.” The Matter With Things, p. 968