Well-Being & Ecology _|_ Issue 21, 2022

Cooking in the Ainu Way

Artist Eiko Soga talks about her experience of living with the indigenous people of Japan

Cooking in the Ainu Way

Artist Eiko Soga talks about her experience of living with the indigenous people of Japan

Eiko Soga is a Japanese-born artist and teacher who has had a long-term interest in exploring new forms of relationship with the natural world. Primarily a video artist, but also working with photography, poetry and installation, she has exhibited her work internationally, (Japan, Germany, the UK, Spain, France, and Italy), and currently teaches at the Chelsea School of Art in London. She also has a background in sociology and anthropology, and has just completed a PhD research project at the University of Oxford which involved living with a community of Ainu people in Northern Japan. We talked to her by Zoom from her home in London about what this taught her about more ecologically-aware ways of living, and in particular, her experience of learning traditional cooking from an Ainu elder.

Jane: Can I start by asking you about the aim of your project with the Ainu?

Jane: Can I start by asking you about the aim of your project with the Ainu?

Eiko: As part of my practice-led research at the Ruskin School of Art in Oxford, I have been looking at the idea of felt knowledge, and how it bridges the relationship between emotion and natural landscapes. In order to do that, I learned traditional cooking with an Ainu elder, Ms Kumagai – known to her friends as Kane-san – who lives in Hokkaido, which is the northernmost island of Japan.

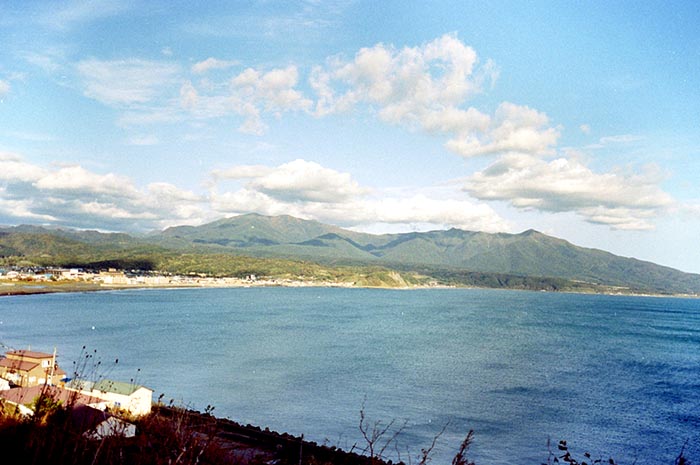

I lived in Hokkaido, specifically in a small town called Samani, for about seven months. Learning to cook in a traditional Samani way started with foraging in the forest and by the sea, then cooking the food, and finally sharing it with the community. An important part of the process was the idea of being in relationship with non-human species. By ‘non-human’ I mean all the resources which are specific to the region and to the Samani people: various different types of seaweed, mountain plants, deer, salmon and salmon roe. They also use some grains, like rice.

Jane: When you talk about ‘felt knowledge’, what do you mean?

Eiko: The term refers to knowledge, skills and information that are experienced through the sensory processes of the body. These are kinds of subjectivities and emotions that can be shared with others; they include things like taste, hearing, smell, touch and vision. I was particularly drawn to smell and colour. In Japanese, we have the word iroka which means both colour and scent, and also includes the idea of being lost – being lost because of the seduction of a person or a place. It is often used for women, or for the attractive atmosphere of a thing, place, or nature. I could say that I was taken by the iroka of Samani – the kelp, the flowers, a bear, a deer, the beauty of Mt. Apoi. So I was drawing that thinking into my research.

Jane: How does the idea of felt knowledge feed into the practice of cooking?

Eiko: Well, there are no recipes in Ainu cooking, so the process of learning always involved me standing or sitting next to Kane-san. I had to really absorb the knowledge by using all of my body: looking, smelling, hearing the sounds, tasting. I used all of these senses to fully embody the knowledge – meaning that I made it part of my own bodily experience.

Using the senses like this really helped me to understand the ecology of natural species. So, for example, when you look at the skin of a salmon, if it’s silvery and shiny, you know the fish came from the deeper sea; if the skin is thicker and darker and has black patches, you know that it comes from the water closer to the river. Those kinds of knowledges are quite important in cooking. Also, we had to rely on our senses to tell whether something was cooked, or whether things were ready to move on to the next stage, because we did not use timers or clocks.

Jane: So what you are saying is that this kind of knowledge is very much based upon observation and experience, rather than on a set of fixed instructions or theories.

Eiko: Yes. Traditionally, in Ainu culture, they don’t have any written texts, so they pass down all their knowledge through oral culture. In the case of Kane-san, she learned cooking from her mother. Also from her aunts and her neighbours, but mainly from her mother, and she did it in the same way as I learnt from her: sitting beside her. Her mother was born at the end of the 19th century, so she retained some knowledge that was disturbed later by the imposition of Japanese culture.

Jane: And was part of her motivation in teaching you that this is dying out now?

Eiko: I wouldn’t say the food culture has died out because it’s still being practiced. It’s just being done in a different way, or using a different approach from maybe 100 years ago, because what people have access to now in terms of resources has changed. I think her interest was to show the diversity of Ainu practice, because the culture as a whole has actually been documented or talked about quite a lot in recent years, but there has been a tendency to see it as a monoculture. She wanted to show how the food is very specific to what’s available in the local landscape, and to leave this knowledge for people in the future, so that in 200 years time, people will still have access to the information.

An Interdisciplinary Approach

.

Jane: So, just to add in some background: the Ainu were one of the original indigenous peoples of Japan. But they were colonised by mainstream Japanese culture in 1868. And, as with many other indigenous cultures such as the Aboriginal people in Australia, there were attempts to eradicate it, or simply to ignore and neglect it.

Eiko: Yes, they were forced to become Japanese in a very aggressive way. They were made to speak in Japanese and behave like the Japanese, and certain of their practices were forbidden; for instance, at the end of the 19th century their tradition of tattooing their bodies – called sinuye – was banned , and they also had to take Japanese names. The majority of people have been assimilated now; only a small number remain who want to remember the traditional ways of life. In fact, there was a time when people considered that there were no native Ainu speakers alive, but now a form of it is being revived and children are learning it privately.

Jane: How did you become involved with them?

Eiko: Actually, the first thing that interested me about the Ainu was their music. (For a taste of this, see Eiko’s video right or below.) I listened to their traditional music for many years in my personal space, and then one day I realised that I didn’t know anything about their culture or history. So I decided to travel in Hokkaido just to teach myself a bit about it. Then I became friends with some of the people, and they introduced me to their friends, and those friends introduced me to their friends and so on. My interest just developed naturally from there. I got to learn about the political aspect of the culture in relation to Japan, and thought that it was really important to understand the effect of colonisation, and to see this in the context of how the world has developed through capitalism and patriarchy.

Video: Marewrew’s Voice, made for The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities, 2021. Duration: 28:55 minutes

Jane: How did this interest transmute into a research project at Oxford?

Eiko: Well, I have a background in both arts and social sciences. I’m also a Japanese woman who has spent more than half of my life in the UK. So naturally, I have thought a lot about our political, social and economic environments. I made that first trip to Hokkaido in 2015, the year after I graduated from the Slade School of Art in London. Since then, I have gone back every year to work within the community, and over time I came up with more and more questions. Studying for my PhD gave me time and space to work on these and build on my existing interests. It is important for people to understand that I’m not doing this research to represent the Ainu people or their culture: I’m doing it as part of my own education in trying to unlearn my social norms, think about things in a different way, and explore what ecology and diversity mean for the Ainu people.

Jane: Your PhD is an unusual one, in that is in Fine Art; it’s not an anthropology project as such, and involved the creation of artworks as well as written material. Your final submission is largely an album of photographs.

Eiko: Yes, for me, art is a space to think and share and document experience – to share the process of communication with people. So, as part of the project I produced some videos and a lot of photographs. I have also written some poetry and used creative writing. I find that non-linear writing structures, such as recording conversations or diary entries, help me to work with things that are unexpected, random or precarious, or doubtful or forgotten – all those qualities that are so difficult to capture. I believe that art is a very productive and positive tool for working with intangible and emotional aspects of the world, and to capture nuanced information and knowledge.

But at the same time, as a result of living in Hokkaido, I have ended up with lots of documents that could be precious and meaningful beyond myself and the art community. So my work overlaps with interests that anthropologists have. However, I don’t really like to call my work ‘research’ or ‘fieldwork’ because I am also part of the community; the people I work with are friends and Hokkaido is my temporary home.

Ms Kumagai (left) and Eiki (right) in the kitchen at Samani; far right, Shino Hisano. Photograph: Eiko Soga

Making Friends with the World

Jane: This matter of acknowledging and trying to express intangible aspects of the world seems to be very important. Do you think that the indigenous people that you have met are more sensitive to these emotional or subtle dimensions of reality?

Eiko: I don’t know if they’re more sensitive, but I think definitely in the culture, the existence of the invisible is quite a mundane part of people’s lives. They are aware of the presence of people who have passed away, or their ancestors, or beings that you don’t necessarily see, such as spirits. Spirits, called kamuy, are quite a strong part of Ainu culture; their belief system has qualities of animism and so they believe that everything in nature, and even objects like tools, have a kamuy [/] on the inside.

But it’s not just the indigenous people who believe in these, because traditionally, or even in modern times, the Japanese also believe in invisible things. I guess because of Kane-san’s age, the traditional ways of thinking she carries or inherited from her mother are very influential and so she expresses them very clearly. When we finished cooking a meal, for instance, we would clean the kitchen and put all the utensils away, and then we would thank them.

Jane: Could you say a bit about Kane-san and your relationship with her?

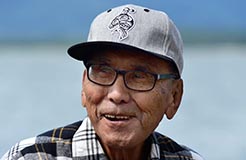

Eiko: I met her in 2019, and from the beginning we got along. She is the 14th child of a mother and father who were both Ainu; her father was one the last hunters in Samani, and her mother was very good at singing. Well known Japanese anthropologists visited her to record her songs. When I met Kane-san she told me that she had been working on projects to preserve cultural practices but she had not yet got round to documenting her mother’s cooking. I realised that this matched my own interest in understanding our emotional and natural landscape, and the way that connecting with felt knowledge contributes to the health – the good health – of human and natural beings.

Jane: Why is it connected to good health?

Eiko: Well, one of the really striking things is that Kane-san speaks to non-human beings, including what we call ‘inanimate objects’, as if they are her friends. And because they’re her friends, she treats them really well. She also acknowledges possible disruptions and difficulties with such friendships. So through her gestures, she supports a very reciprocal relationship between people and non-human beings. I’m not sure if this is typical of Ainu culture, but I feel that such gestures lead to a more ecological way of living a human life.

For example, when we were foraging, we made sure we didn’t pick all the plants we saw or that were available because we needed to leave some of them for other animals or insects. Also, we had to make sure those plants would come back the next year. So we ensured that we would have food on the table every year to stay healthy, because without those relationships with non-human beings, we would end up dying. It can’t be that one species wins and consumes everyone else; that doesn’t allow the whole ecology to keep working or functioning.

Jane: So would you say that one of the aspects of this felt knowledge is an acknowledgement that human beings are part of nature, and that we have faculties which allow us to be sensitive to the nature and needs of other beings?

Eiko: It’s also about listening to what things communicate, and understanding our own system as well. I’ve been interested in this sort of knowledge because the emotional and intangible aspects of life have been dismissed for many years as non-reliable information. But humans are emotional creatures and we feel all the time, and we learn so many things from sensory knowledge. For example, one of the local hunters caught a bear, and I asked him whether I could be there when he cut it up. I gained so much understanding about this massive creature from just the smell and the images. It was only about four years old, so it was just a child, but it was already about 400 kilos. It was just before the winter, and so it was packed with food, preparing for hibernation.

Such an experience raises all sorts of questions. It was not fair to this bear that it had been killed, and the hunting practices of indigenous peoples have been very much criticised as cruel by outsiders – by people who perhaps want to romanticise their way of life. But it has to be understood that they just have a very different relationship to the world. The bear has had a very important place in Ainu culture, and when one was killed they used to enact a ceremony to send its spirit back to where it belongs. This is not practiced now, though.

The beach, Samani: Photograph: Eiko Soga

Unlearning

.

Jane: But still, the question of correct relationship with the natural world remains.

Eiko: Yes. I have said that Kane-san treated non-human beings like friends, but friendship doesn’t just mean positive, happy things. It includes the possibility of disruptions and difficulties. When receiving the gift of mountain plants, for example, we are taking away food from insects. How much can we receive? How much do we need to protect ourselves? How much do we need to preserve? We become involved in a subtle, nuanced, very complex relationship which is a really difficult balance, but I feel that if we are more tuned into our bodies, balancing data and external information, we can be more aware of social cues or visual cues that help us negotiate it. So, I encourage collaboration between people from different fields.

The problem of course is that this natural response to nature may have been suppressed by living in big cities. When we’re in a city, we have to suppress our senses so as to cooperate in that densely populated space where there is very little connection with nature.

Jane: You talk a lot in your PhD about unlearning your habitual modes of operation.

Eiko: The unlearning was important because I was raised and educated in Japan and England, both countries that took on the role of colonisers And I often thought about what it means for me to be educated by those cultural norms. Kane-san insists that what she’s doing when she cooks, or when she is involved in other aspects of Ainu culture, is nothing special. It has only become special because her culture was colonised and a different set of values imposed.

One of the things that was important in my research was the need to not romanticise Ainu culture. As Trinh T. Minh-ha has pointed out in her film Reassemblage,[1] which followed a group of women in Senegal, we need to watch out for our ‘habit of imposing meaning to every single sign’. Because I saw Kane-san’s teachings through my own social norm, I would see her doing something and ask: did this come through your culture? And sometimes she would say: oh no, this is just something that I do. So it was important to understand that some things that were different were just her unique gestures.

Jane: You also make the point that these cultures change – that there is not some past, idyllic state which we would call ‘traditional Ainu culture’; there has always been development and adaptation within the culture itself.

Eiko: That was really important when working with Kane-san, as sometimes we would use some new technology during cooking. Often she preferred traditional methods, so when we were grinding rice into powder, we would use a wooden mill even though it was very hard work and took a long time. But because I was there during lockdown, we also used plastic gloves to protect ourselves from sharing the virus. So they keep adapting, and adopting new things if they are good.

The other thing is that the communities have changed over the years and one cannot romanticise about the social relationships. People have a lot of problems now resulting from oppression and discrimination, inherited trauma, etc. So we have to deal with the society as it is, not in some idyllic past.

Winter in Samani. Photograph: Eiko Soga

The Dancing Kimono

ing.

Jane: The other activity that you participated in was kimono making. In particular, you helped with a traditional kimono that Ms Kumagai is making for the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford.

Eiko: The kimono was something I did mainly during winter. During the winter months, which are very very cold in Hokkaido, we couldn’t do much cooking in terms of traditional meals because we didn’t have many natural resources to cook from.

Jane: So what did people eat?

Eiko: Traditionally there are a lot of preserved foods – things like fermented potatoes, which Kane-san ate as a child. Also Kane-san broke her arm, so instead of cooking, I worked alongside her whilst she made the kimono for the museum. It is not finished yet but it should be done by the end of the year. There were a group of about six women working together on their kimonos in the community centre, and I would go and sit with them, in silence or sharing gossip – not in a horrible way, but just learning the local knowledge through everyday activities.

One of the favourite things I learnt from Kane-san was about the kimono. In the cooking, there is no recipe or right way of making a dish, so you just have to use your felt sense to decide whether it is good. So I asked her: how do you tell when a kimono is good? And she said: you pick it up and stand back a little, and if it is good it dances.

Jane: How does the kimono get made? I assume that they don’t have paper patterns like we do for clothes?

Eiko: Kane-san’s is based on an old Samani kimono which is in a museum now. The basic method of making a kimono is like doing origami; you follow the shape of the textile to make folds, using the straight line of the edges of the textiles. Traditionally, each household, or each village had their own embroidery pattern. They didn’t use rulers or measuring tapes, so they would measure the size with their fingers. So naturally, the size of the kimono becomes not perfect, not even, which makes each one quite unique.

Also, everything is sewn by hand, so they talk about listening to your hands. Each hand – each person’s hand – is unique and has its own special movement. So if you listen to your hands, the kimono becomes unique because of that as well.

The embroidery on the finished kimono. Photograph: Eiko Soga

Wider Relevance

.

Jane: I know that you are very concerned about the ecological crisis, and a lot of your artwork questions how we can change our relationship with the natural world. How does the understanding you have gained through your contact the Ainu help us with these problems?

Eiko: That’s a very big question and I don’t know that I should even try to answer it. One thing I could say is that I always feel that our behaviour is based on our emotions; maybe not always but often. That’s why I’ve been interested in sensory knowledge – because of how this emotional aspect impacts on our natural environment. So, really important is what I said earlier about making friends with non-human beings on a daily basis and being kind to objects and plants – being empathetic; giving them the space they need. We live in a world where we just consume things and throw them away, filling the land with garbage. But if we can just appreciate an object as a lifelong friend, it reduces the possibility of creating more rubbish.

The other thing is the importance of bringing many different kinds of knowledge together. It has been very much part of my research to set up collaborations with other academics, especially scientists and agencies such as local government. There is an incident which illustrates this very well: I have talked about how Kane-san has lots of knowledge and insight about her local environment. Well, whilst I was in Samani, I made contact with some of the local scientists who were working on protecting the natural species in the Hokkaido area and doing research on them. I also met some members of the local town government, who were passionate about nature. And I found that that they did not know about some of the species that Kane-san knew about.

There is a plant called ento, for instance, which is a minty-flavoured leaf used for making herbal tea in Ainu culture. It is delicious, and Kane-san would ask her friend to drive her in her car to the areas where it grows in order to gather it. But the scientists and the government did not know about its existence in this region, so when they were constructing the roads they would destroy it. And you know, once the plants are gone, they are gone; they don’t grow back.

So I talked to the town government people about this, and they were so surprised to hear about this plant. Now they can protect it, and also make it part of their promotion to attract tourists that they are preserving a species important to the Ainu. Kane-san is not in a position to make contact with a state-organised project, so I acted as a mediator. She lives in the same small town as these government officials; they know each other’s faces on the street. So how come they are not exchanging their knowledge?

So I think interdisciplinary interaction is really important. And this means respecting the contribution of all kinds of different knowledge-holders. Very often, the knowledge that someone like Kane-san has is not seen as valuable, and it is the knowledge of people who have university qualifications or official positions that are listened to. Nowadays, there are Ainu children going to universities in Japan, and this is obviously a very good thing. But Kane-san worries about what effect this will have, because she sees that Ainu culture is a different kind of knowledge which is gained from everyday living – from living in a certain sort of way. We need to be including both sorts if we are to really look after our environment.

To find out more about Eiko’s work as an artist,

see her website www.eikosoga.com

Here is a video where she shows how salmon skin can be used to make shoes [/].

And here is another video she had made on traditional music:

Video: Tonkori: Music Conservation with Oki. Oxford Centre for Research in the Humanities. Duration: 61:01 minutes

Image Sources (click to close)

Banner: Eiko and Kane-san foraging for seaweed on the shore. There are four different varieties of kelp used in traditional cooking. Photograph: Maki Kurisu.

Inset: Map of Hokkaido. Samani is in the south east of the island.

End: Butterbur foraged from the forest. Photograph: Eiko Soga.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] TRINH T. MINH-HA, Reassemblage: From the Firelight to the Screen (Strictly Films, 1982).

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

Video: Marewrew’s Voice, made for The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities, 2021. Duration: 28:55 minutes

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Paddling the Magic Canoe: The Wisdom of Wa’xaid

Briony Penn talks about her relationship with the native elder Cecil Paul – Wa’xaid – and their successful campaign to preserve the glorious Kitlope River area in British Columbia

Fighting Fire with Fire

Victor Steffensen talks to Rosemary Rule about his pioneering work reintroducing indigenous cultural burning practices in Australia

The Unity of Bee-ing

An interview with Heidi Herrmann about the work of The Natural Beekeeping Trust in preserving our precious population of bees

Poacher’s Pilgrimage

A journey with Alastair McIntosh – poet, theologian and environmental activist – to the sacred sites of the Isle of Lewis

READERS’ COMMENTS

What a terrific article. I learned a lot. The sense of “feeling” life and the recognition, respect, and appreciation for “inanimate” objects of existence all resonated with me. If matter and energy are one and the same, we ask, “where is self”, “what is life”, and “is some basis for consciousness and intelligence somehow present in all things”. The Ainu and Kane-san and others that understand and experience the world with a sense of feeling life and respecting and relating to not just animate life but also inanimate things benefit, I feel, from a broader and more balanced engagement with the world in and around them. Thank you to Elka Soga for bringing this awareness to others! Thank you for sharing this article!

Such an informative and heartfelt interview. I hope that your learnings and knowledge can be shared with Japanese citizens so that they may become more aware and respectful of their indigenous population.

https://www.google.com/