News & Views

Poems for These Times: 17 – March 2022

Calamity Again

by Taras Shevchenko

Calamity Again

Dear God, calamity again!

It was so peaceful, so serene;

We had just begun to break the chains

That bind our folk in slavery,

When suddenly…! Again the people’s blood

Is flowing. Like dogs hungry

For butter, the royal thugs

Are at our throats again.

The poem was written in 1859, two years before Shevchenko’s death, but it seems as relevant today as it did in his own time, when many Ukrainians (as well as many dissident Russians) were struggling against the oppression of the Tsarist state. His reference to slavery in the poem was not simply a rhetorical flourish. He was born in the village of Moryntsi, south of Kiev, in the geographical heart of Ukraine, into a family of serfs who were owned as private property by the German-Russian landowner Vasily Engelhardt. Shevchenko claimed Cossack ancestry, and his forefathers had taken part in a number of rebellions against Russian domination before they were defeated and enslaved.

The poem was written in 1859, two years before Shevchenko’s death, but it seems as relevant today as it did in his own time, when many Ukrainians (as well as many dissident Russians) were struggling against the oppression of the Tsarist state. His reference to slavery in the poem was not simply a rhetorical flourish. He was born in the village of Moryntsi, south of Kiev, in the geographical heart of Ukraine, into a family of serfs who were owned as private property by the German-Russian landowner Vasily Engelhardt. Shevchenko claimed Cossack ancestry, and his forefathers had taken part in a number of rebellions against Russian domination before they were defeated and enslaved.

Taras was a precocious child who proved to be a talented painter as well as writer: in Ukraine today, besides his status as the national poet, he is recognised as an important artist. His gifts were appreciated by his master, who began to take the young man with him on official business within the Russian Empire, and particularly to the then capital, St Petersburg. There he was enrolled in art studies, and subsequently attracted the notice of both Ukrainian and Russian artists and writers. His friends were eventually able to collect enough money to buy his freedom in 1838, when he was 24 years old.

After this Shevchenko established himself in the imperial capital, becoming an important figure in émigré Ukrainian circles, as well as mixing with other Russian writers, artists, and intellectuals. Most of these figures (whether Ukrainian or Russian) were opposed to the extreme authoritarianism and repressiveness of the Russian state under the Emperor Nicholas I (known as ‘the gendarme of Europe’), and Shevchenko became increasingly involved with intellectual and political movements dedicated to gaining greater freedom for the empire as a whole.

He had already begun writing poetry in his native Ukrainian while he was still a serf, and in St Petersburg in 1840 he published his first collection of verse, entitled Kobzar (‘The Bard’), a title which was subsequently given to his collected poetic works and also to the poet himself. At first his poetry dealt with traditional Ukrainian themes – nostalgic and Romantic depictions of Cossack life – but over time it became more overtly political and serious as he directly addressed the oppression and sufferings of his people. Though he was based in St Petersburg, he travelled widely in Ukrainian lands, and was moved to paint and write in response to what he saw and felt: the wide plains of the southern steppes, the towns, villages, monasteries and churches he visited there, and life and customs of the people (often peasants). He is regarded as a seminal figure in establishing Ukrainian as a distinct language, with its own literature and spirit.

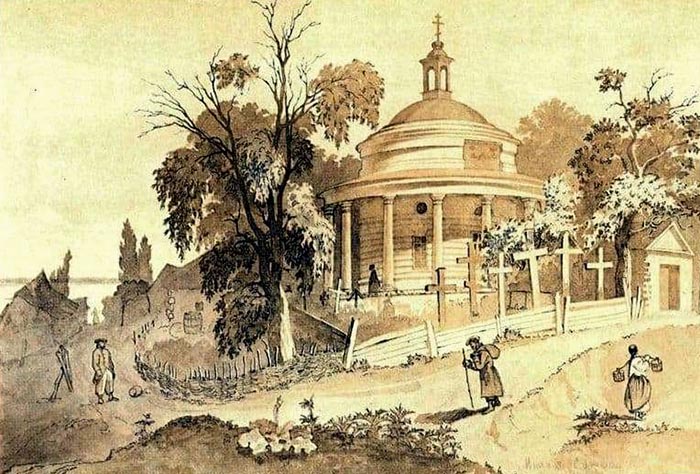

Askold’s Grave by Tara Shevchenko. An engraving showing an historic monument in Kiev where the 9th century Ukrainian Prince Askold and his brother Dir are buried. It is considered a sacred site by the local people. For more, click here [/]

However, his involvement with dissident groups in St Petersburg attracted the attention of the Tsarist authorities, and in 1847 the publication of a poem mocking the imperial family led to his arrest and exile to a remote area of the empire, 1000 miles southeast of Moscow, near the modern border with Kazakhstan. He was to remain there for many years, cut off from the intellectual milieu of the capital and also from his own homeland. The document giving his sentence bore the following comment written by the Tsar himself: ‘Under the strictest surveillance, without the right to write or paint’. This was a condition that Shevchenko himself was, by and large, able to ignore, and he continued to write and paint throughout his exile.

At the same time, as the idea of a distinct Ukrainian language and separate cultural identity came to be viewed with suspicion and hostility, his work was banned in the Russian Empire and confiscated from libraries and bookstores, as well as from individual citizens. Just like today, the Russian imperial government increasingly denied the Ukrainians the right to be considered a distinct people. Shevchenko’s work was itself the most potent and eloquent witness against this thesis, and remains to this day a classic expression of Ukrainian identity and sensibility, expressed in the Ukrainian language itself.

In arousing the personal and vindictive hostility of the Russian autocracy, he was not alone. The same happened to Mandelstam, Shostakovich, Pasternak and numerous other artists under Stalin, and to many journalists and dissidents under Putin – some paying for that disfavour with their lives. The great national poet of the Russians themselves is Alexander Pushkin (1799–1837), who was also exiled and persecuted by the imperial authorities before dying in a duel which many believe to have been deliberately instigated by Tsar Nicholas himself. Throughout its modern history, the conscience and creative soul of the Russian people has been distinct from, and often in opposition to, the authorities who rule them, even if those authorities subsequently seek to manipulate the reputations of the persecuted artists for their own purposes.

Shevchenko was only released from the sentence of exile after Tsar Nicholas’s death in 1855 and the accession of his son Alexander II, whose liberal sympathies aroused new hope among those awaiting an easing of Tsarist oppression. But the poet’s health had been broken after the long years of serfdom, exile, and political oppression, and he died in 1861 at the age of 47. A few months later, the new emperor finally decreed the ending of serfdom in the empire.

However the subjects of the empire continued to experience its random and ruthless brutality, sometimes without warning. Even under the new Tsar, the Russian state and its agents (the ‘royal thugs’) continued with extraordinary brutality to sow division and suffering in Ukraine, attempting to ensure that hopes of autonomy and self-expression would not be fulfilled. This found its most devastating expression in the ‘Holodomor’ during Stalin’s reign, a famine deliberately created by the Soviet authorities to bring the Ukrainians to heel, which led to the deaths of around three million people.

As with all great poets whose works have a particular appeal for their own people, the work of Shevchenko speaks to all mankind, with its themes of longing for freedom and peace, its depiction of injustice and dread, its love of people, landscape, and nature. Though in ‘Calamity Again’ he is describing a particular Ukrainian experience, he is also speaking to all of us who believed that the events taking place today were something of the past, something we had outgrown on this continent. We believed we were now in a different phase of human development, no longer engaged with existential survival, or in naked struggles for power and control, but rather in breaking the chains of slavery – extending freedom and justice in the societies in which we live. But now the dogs are once again at the throats of the Ukrainian people, and for many of us who are watching from the sidelines, their struggle is also our own.

The Taras Shevchenko National Academic Theatre of Opera and Ballet in Kiev, founded in 1867. The Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv is also named after him, as is main boulevard in the city centre. Photograph: OlyaSolodenko/istock

Banner image: Izyum, Ukraine, March 4, 2022. A damaged retail store, bombed by Russian army aviation forces, killing eight civilians. Photograph: Rizvanov Ruslan [/] / Shutterstock.

Inset: Taras Shevchenko, photographed by Andrey Denyer [/], c. 1859.

More News & Views

Don’t Take It Easy

Richard Gault is inspired by Michael Easter’s book The Comfort Crisis and explores the idea of ‘misogi’ during a 600-mile walk across Scotland

Book Review: ‘The Serviceberry’

Martha Cass contemplates the message of a new book by Robin Wall Kimmerer that advocates ‘an economy of gifts and abundance’

Book Review: ‘Conversations with Dostoevsky’

Andrew Watson engages with an innovative new book by George Pattison which explores Dostoevsky’s relevance in the contemporary world

Thich Nhat Hanh & the Poetry of Engaged Buddhism

Philip Brown presents the poem ‘Recommendation’ and comments on the potential of contemplative art to foster compassion

Introducing… ‘Perfect Days’ and ‘Nowhere Special’

Jane Clark watches two films with a contemplative theme

Book Review: ‘Irreducible: Consciousness, Life, Computers and Human Nature’

Richard Gault reviews a new book by Federico Faggin, one of the leading lights of the science of consciousness

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READERS’ COMMENTS

9 Comments

Submit a Comment

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

Thank you.

“Poetry is a sword of lightning ever unsheathed,

which consumes the scabbard that would contain it” P.B.Shelley

“The pen is mightier than the sword” Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton

“The meal is mightier than the missile – it brings people together, does not blow them apart” Charles Mugleston

How I wish a Master Chef would invent ‘Kremlin Crumble’

As a poet myself, I’ve felt and expressed the pain of the Ukrainian people. Over so many years, I weep at “Calamity Again.” One of two poems I’ve written so far about the current tragedy contains these lines:

“how many thousands will be killed this time?

how many futures fed into the meat grinder?

how many stunned hearts riddled with grief?

I try to block up my ears shut tight my eyes

but the rivers of blood keep pouring through”

We poets must witness! I stand in solidarity with Taras Shenchenko and the Ukrainian people.

I too thought we were past such things in Europe.

As we are not and putinesque figures can lead nations to war, whether in Europe or world-wide, imv we need to strengthen international law and the international forces necessary to bring such leaders to trial.

Say, formed by SAS-like marines of G-8 or G-20 nations on secondment to the UN, on 3-year rotation.

Under a reformed UN. With rotating G-8 Permanent Members of the Security Council, with majority voting.

I had heard of his name, but a FB friend has posted one of his poems, and I am in awe.

Here is a short excerpt from a memory piece by poet Greta Briggs, circa 1940-41):

“London Under Bombardment”

“But other lights keep burning, and their splendour, too,

Seen in the work-worn faces and glimpsed in the steadfast eyes

When little homes lie broken and death descends from the skies.

The bombs have shattered my churches, have torn my streets apart,

But they have not bent my spirit and they shall not break my heart.

For my people’s faith and courage are lights in London town

Which still would shine in legends though my last broad bridges were down.”

I’d like to submit this saying I’ve often referred to in times of need:

“In the depth of winter I finally learned that there was in me

an invincible summer.”

Albert Camus

A wonderful and inspiring piece by Andrew: thank you.

I wonder

how many times

we need

to be taught

the folly of

naivité?

Comprehensive, informative and relevant article. Thank you.

Here is a contemporary poem sent in by a reader:

Babi Yar Revisited: A Poem of Remembrance

by Paul Finegan

Babi Yar Revisited is inspired by the poem ‘Babi Yar’ by Yevgeny Yevtushenko

In 1941 at Babi Yar, on the outskirts of Kyiv, in Northern Ukraine, the Germans slaughtered over 30,000 Jews in 48 hours.

In 1961 the Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko visited the site of the massacre and wrote the celebrated poem ‘Babi Yar,’ in part in protest at the Soviet government’s lack of provision of a Memorial on the site, and because of continuing Antisemitism in Russia.

In 2022, on the second day of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the army shelled the site of the Babi Yar massacre with a missile strike, intending, it is thought, to hit a nearby communication tower.

Wild grasses rustle still in Babi Yar

leaves spiralling in the wind, rising in the air like the souls of those who died,

and who are dying now, each leaf in memory of those massacred here,

over 30,000 Jews, Ukranians, Soviet prisoners, Romanies and more,

bullets scattered careless on the ground, bodies covered over,

like the truth hidden in one deep grave.

Now falling shells and missiles blight the memorials here,

and the booming sounds of war shock our souls as a new terror is unleashed.

Here it is humanity itself denied as we are driven into cellars,

loved ones gathered close on the borders, searching for a final kiss,

tears like pearls staining cheeks.

Soon this land will have no men, only fighters and those fleeing,

whole lives fractured and squeezed into battered suitcases.

Would Yevtushenko proudly stand as Russian still?

And as for me, do not ask my nationality,

for we are all Ukrainians now.

We are dipped in the colours of humanity and held close by love that can never be lost.

Do not weep for us here in Babi Yar,

weep for humanity itself.

And do not think that love is lost, or hope denied.

Our voices covered over in the burial ground still declare the mute testimony of the dead,

that love is never lost.

We speak with one voice that can no longer be covered over,

we stand for love itself, with truth standing by our side.

Wild grasses rustle still in Babi Yar, and we are all Ukrainians now,

Despite the snaking lines of tanks and cities shelled,

we are dipped in the colours of humanity,

for humanity can never be denied, nor human dignity destroyed.

And as for me, do not ask my nationality,

for we are all Ukrainians now, the planet wide