News & Views

Making Paradise: Exploring the Concept of Eden through Art and Islamic Garden Design

Jane Clark visits an exquisite exhibition at the Aga Khan Centre in London, and talks to its creators, Esen Kaya and Emma Clark

Installation view, showing ‘The Silent Fountain’ and the back wall. Photograph: Jonathan Goldberg. Courtesy of the Aga Khan Centre Gallery

This small but beautifully conceived exhibition at the new Aga Khan Centre in Kings Cross is an oasis of peace and tranquillity in the midst of the city. As such, it reflects its subject matter, which is an exploration of the Islamic notion of the ‘paradise garden’ which for centuries has inspired the creation of beautiful gardens from the Taj Mahal to the Alhambra. Bringing together an eclectic range of art works both ancient and modern, eastern and western, the exhibition aims to give visitors a taste of the contemplative space which these great gardens provide, and a chance to reflect upon their own imaginative conceptions of Eden.

The depiction of paradise as a garden where waters flow and plants and fruit-bearing trees flourish in perfect harmony is a central motif in the Qur’an, but this exhibition makes clear that the notion has universal relevance. As the curator, Esen Kaya, explains: “The very word ‘paradise’ fills us with joy. The idea of a place which gives us ultimate peace and happiness is common across all faiths and spiritual beliefs, and my idea was to invite artists to respond to this theme by bringing their own interpretation of what this means to them.”

Karen Nicol, ‘Into the Blue’; mixed media on canvas. Photograph courtesy of the Aga Khan Centre Gallery

An important part of her conception was that the exhibits should span a range of cultures and eras. On the back wall, traditional 16th-century miniatures from the Aga Khan Museum sit alongside 19th-century European prints depicting fruits commonly found in Islamic gardens – figs, apples, pomegranates and grapes – which have been lent by the Royal Horticultural Society. A striking feature is the number of works by contemporary artists. Many of these have been specially commissioned, and there is a particular connection with The Prince’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts in London, which draws artists from all over the world to learn or extend traditional skills (see our article on Keith Critchlow). There is also a variety of media – ceramics, tapestries and embroidery as well as watercolours and canvases.

“Exhibitions come to life when people engage with them,” says Esen. “So I wanted to ensure that this one appealed to a really broad audience. For many Muslims, gardens reflect the bounty of God and the blessings of life. But they are also secular realms of social intercourse, pleasure, romance and diplomacy, as well as a retreat from the hardships of work, conflict and harsh environments.”

Jethro Buck,‘Fig Tree’: pigment gum and 23 carat gold leaf on hemp paper. Photograph courtesy of the Aga Khan Centre Gallery

A Multi-sensory Experience

.

In order to recreate the total atmosphere of a paradise garden, the exhibition provides a multi-sensory experience. As visitors enter, they are wafted by the delicate ‘paradise perfume’ specially created by Alessandro Cancian, and their ears are soothed by a soundscape by Geoff Sample which includes the evocative songs of nightingales, hoopoes, golden orioles and crickets.

The exhibition itself is laid out according to a four-fold geometry (chahar-bagh) – a classic feature of the Islamic garden which, using the four walls of the gallery, is cleverly recreated by the symmetrical hanging of the pieces. The symbolism of four runs through all Quranic accounts of paradise; there are four gardens (two higher, two lower); four rivers (of water, milk, honey and wine), and four trees (the date, olive, fig and pomegranate). These last are represented in the exhibition by four specially commissioned paintings by the young British artist, Jethro Buck, whilst Yasmin Hayat’s glazed plates add four flowers (the tulip, narcissus, carnation and rose) to the mix. The wonderfully vibrant ‘Dance, sparkle, flow’ by Australian painter Ross P. Taylor takes four-fold symmetry as a structural layout, using the different quadrants to combine real landscapes from Central Victoria with imagined gardens lush with the trees, fruit and flowers seen in traditional Islamic paintings.

Ross R Taylor, ‘Dance, sparkle and flow’: synthetic polymer and pencil on canvas. Photograph courtesy of the Aga Khan Centre Gallery

Another central feature of the paradise garden is water. But here Esen encountered a problem, as there is no running water in the gallery. A solution was found in the creation of what she called a ‘poetic fountain’ and she invited the well-known expert on Islamic gardens, Emma Clark, who also acted as consultant to the exhibition, to design it. The final result, ‘The Silent Fountain’, is pure white and consists of a square base on which is placed an octagon, then a circular bowl. “The square is the symbol of the earth,” Emma explains, “and the circle is the symbol of the celestial realm, and the octagon – the number eight – represents the transition between the earth and heaven. And this is one of the functions of these gardens; to make a link between the higher and lower realms”.

The water is represented by beautiful, cut-out strips of white paper depicting flowers and birds, designed and produced by the Berlin artist Clare Celeste Borsch. “I really cannot exaggerate the importance of water in an Islamic garden,” Emma goes on. “It says in the Qur’an: ‘From water We created every living thing’ [1] and it really is true that without water there would be no life. Water is also seen as the reflection of the soul, and when you walk around an Islamic garden, you almost always end up sitting by water. If it is calm and serene, then it has a calming effect upon us, and if it is moving, it energises us as well as bringing in the elements of light and sound, so that all the senses are engaged.”

Clare Celeste Borsch, detail of the ‘water’ in The Silent Fountain: laser-cut paper strands. Photograph courtesy of the Aga Khan Centre Gallery

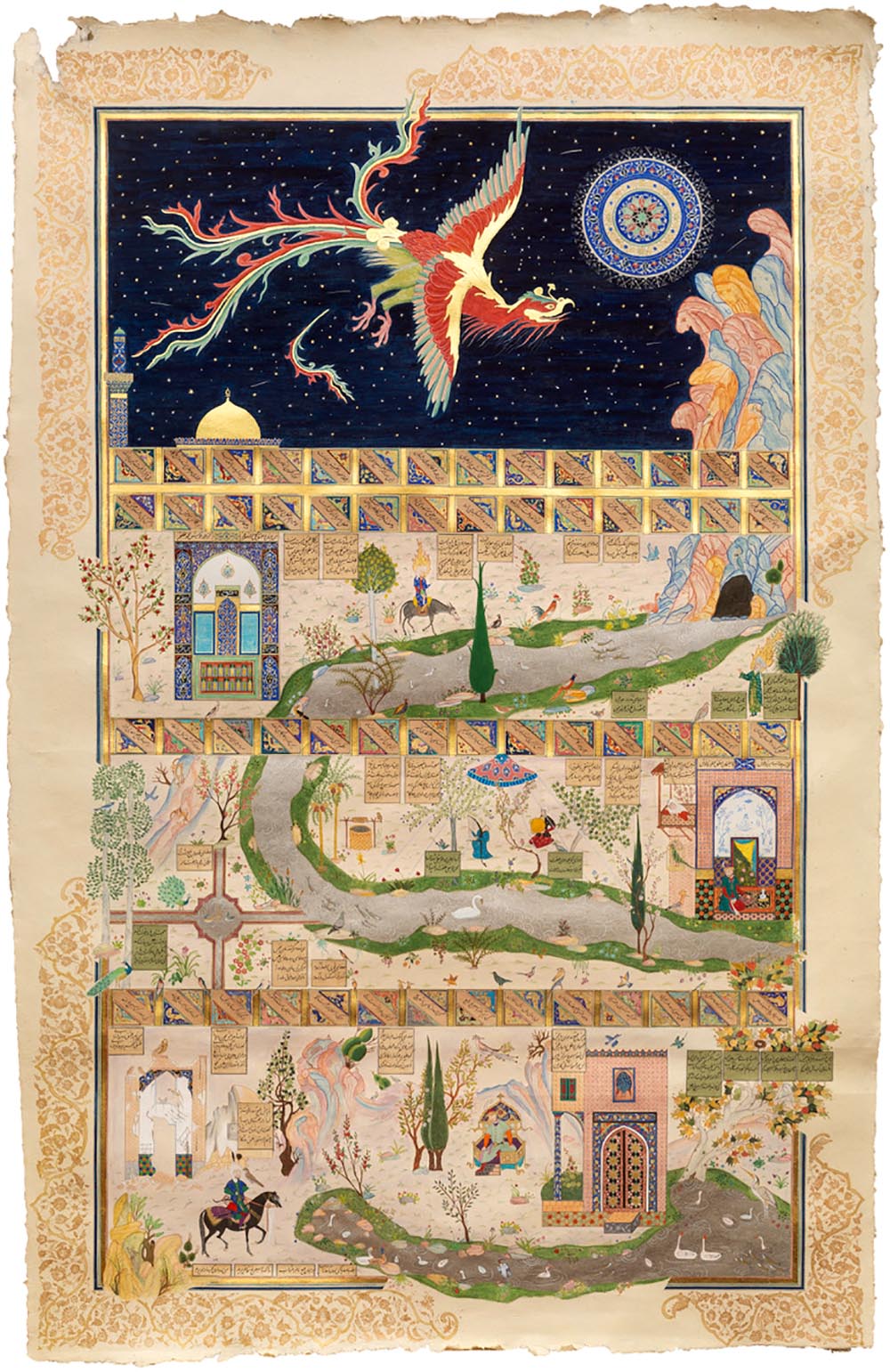

The largest piece in the gallery, taking a central position on the back wall, is a stunning new work by Iranian-born artist Farkhondeh Ahmadzadeh entitled ‘Canticle of the Birds – Debating the Journey’, which has been inspired by her many years of studying the epic 12th-century poem by Farīd al-dīn ʿAttar. Farkhondeh teaches miniature painting at The Prince’s Foundation School, and the translation of her skills to a larger scale has produced a painting full of wonderful detail and intricacy which is worthy of hours of contemplation in itself. Another large-scale work which I particularly enjoyed is the ‘Gardened Wall’ which greets the visitor in the corridor leading up to the gallery; this has been created by the Moldavian-born embroiderer Olga Prinku from a cheerful array of dried flowers – mountain daises, strawflowers, golden ageratum – to create the effect of ‘walking through a summer meadow in paradise’. [2]

Farkhondeh Ahmadzadeh, ‘Canticle of the Birds – Debating the Journey’: watercolour made with hand ground natural pigments in gum Arabic. Image: courtesy Farkhondeh Ahmadzadeh

Move your mouse over the image to enlarge

Garden Projects

.

It is no accident that this exhibition is happening at this new Aga Khan Centre, which is situated in a 67-acre development site behind Kings Cross Station in central London. As Esen explains, for every new project, HH the Aga Khan lays out particular aims in addition to the over-arching intention of cultivating education, cultural exchange and insight into Muslim civilisations. In the case of London, a great cosmopolitan city, these aims included multi-culturalism and gardens. Nine small gardens have consequently been incorporated into the state-of-the-art building, created by a several different designers with the brief of reflecting the diversity of styles found across the Islamic world. (For more on these, see video right or below.)

Video: Islamic Gardens at Kings Cross. Duration: 11:04

They include two roof-top gardens – the Garden of Light based on Andalusian architecture and the Garden of Life based on Moghul designs – and a number of smaller ones such as the Terrace of Learning adjunct to the library and the Garden of Unity based on Moroccan traditions Outside, there is another garden nearing completion – the Jellicoe Garden – designed by Tom Stuart-Smith and inspired mainly by Persian and British styles. This will be a free, public space accessible to everyone, and is part of the larger conception of creating a ‘green corridor’ in this highly urbanised area by linking with other amenities.

At a global level, the Aga Khan Development Network as an organisation has done much to promote the development of gardens and green spaces all over the world. As part of the exhibition, there is a short film, ‘Islamic Gardens: Catalysts for Change’, which describes the creation of parks in cities such as Cairo, Kabul, Delhi and Bamako, where rapid urban development has tended to remove space from the public domain, leaving the local population with no way of spending time with nature, taking exercise or meeting with one another. The al-Azhar Park [/] in the centre of Cairo, for example, was created by turning a rubbish dump into a spacious landscaped park open to everyone.

The Garden of Light, designed by Nelson Byrd Woltz; one of the rooftop gardens at the Aga Khan Centre in London. Photograph: Aga Khan Centre [/]

Finding Peace

.

The importance of green space where we can reconnect with the natural world has become particularly clear over the past year, when many of us have found our gardens and parks to be life-lines during the enforced seclusion of the Covid pandemic. The idea of the paradise garden, which creates a beautiful, harmonious space where we can contemplate the beauty and unity of both the creation and the divine, adds a further dimension to this awareness. The key concept, it seems, is peace. Describing the purpose of these gardens in a recent talk organised in collaboration with the Royal Horticultural Society, Emma pointed out that the only word spoken in paradise, according to Qur’an 56:25, is salaam (peace, completion). She concluded:

Whether we have a religious faith or not, we probably all have an idea of what paradise means to us. It may not be the eternal gardens described in the Qur’an, but rather it may refer to a consciousness of the here and now, a contentedness free from worry and mental unease… Profound peace of heart and mind is what paradise is all about. A paradise garden on earth may help us with this endeavour, but on a deeper level it may prompt us to take a long meditative breath to remember that there is peace available to us at all times if we consciously slow down and remember.[3]

Yasmin Hyat, ‘Pomegranates and Carnations’: 35cm glazed earthenware coupe plate. Photograph courtesy of the Aga Khan Centre Gallery

Making Paradise is open until 30 September 2021 at the Aga Khan Centre, Coal Drops Yard, 10 Handyside St, London N1C 4DN. Click here for information on how to book.

For our many readers who will not be able to visit in person, there is a web-site where the exhibition can be viewed digitally (click here [/]) and a video (see right or below) featuring both Esen and Emma which gives a very good taste of the exhibition and the gardens at the London centre.

Video: Making Paradise. Duration: 13:42

More News & Views

Don’t Take It Easy

Richard Gault is inspired by Michael Easter’s book The Comfort Crisis and explores the idea of ‘misogi’ during a 600-mile walk across Scotland

Book Review: ‘The Serviceberry’

Martha Cass contemplates the message of a new book by Robin Wall Kimmerer that advocates ‘an economy of gifts and abundance’

Book Review: ‘Conversations with Dostoevsky’

Andrew Watson engages with an innovative new book by George Pattison which explores Dostoevsky’s relevance in the contemporary world

Thich Nhat Hanh & the Poetry of Engaged Buddhism

Philip Brown presents the poem ‘Recommendation’ and comments on the potential of contemplative art to foster compassion

Introducing… ‘Perfect Days’ and ‘Nowhere Special’

Jane Clark watches two films with a contemplative theme

Book Review: ‘Irreducible: Consciousness, Life, Computers and Human Nature’

Richard Gault reviews a new book by Federico Faggin, one of the leading lights of the science of consciousness

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

Video: Islamic Gardens at Kings Cross. Duration: 11:04

Video: Making Paradise. Duration: 13:42

Sources (click to open)

[1] Qur’an 21:30.

[2] Olga Prinku in the exhibition catalogue.

[3] EMMA CLARK, Introduction to the Key Elements of the Islamic Gardens of Paradise, a talk at the Aga Khan Centre, London, 30th June 2021.

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READERS’ COMMENTS

4 Comments

Submit a Comment

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

“HERE with a Loaf of Bread beneath the Bough,

A Flask of Wine, a Book of Verse -and Thou

Beside me singing in the Wilderness –

And Wilderness IS Paradise E’ NOW”

Quatrain 11 from the Ruba’iya’t of Omar Khayya’m translated and adapted by Edward FitzGerald

Dear Jane, GLORIOUS! Thankyou.

So utterly beautiful, I am inspired. Thank you.

The story goes that we were expelled from this paradise, but we left it of our own accord and now seem determined to trash it. How could this have happened? How can we stop ourelves? Your review makes this question more poignant; more urgent. Thank you.