News & Views

Reflections: Covid Refuge

Writer Robert Hirschfield contemplates the experience of locked-down New York

Liberty Park boardwalk by the Hudson River, New York. Photograph: amintang/iStock

I’d walk to my spot on the promontory, my back to the city. Last March, as New York’s lockdown began and our body count mounted, I wandered out as far as was humanly possible along the Hudson River, feeling at once treasonous and relieved. Separated from my shuttered Poets House with its 70,000 poetry volumes and my armchair by the broad window that might as well have had my name carved into it, I contemplated the strangeness of beginning again as a writer in the open air, by the water, amidst the mass cloistering of New Yorkers in their homes. Staying sedentary, even in sickness, is a trait that has always eluded me.

Walking the virtually empty streets, past darkened shops and cafés, I had the feeling I was on the set of some cheesy disaster movie that was temporarily abandoned by the crew. There was the strong sense of dreamscape, as if you had mistakenly wandered into a foreign land. Once, in a dream, I glimpsed India from behind a tree. An enormity reduced to a fragment, like the hand-printed sign in a shop window assuring everyone this would soon pass.

A native New Yorker, I’ve lived my eighty-one years in a city whose splendid enclosures have fetishized culture and commerce. Now, I find myself thinking, it has to resurrect itself, get closer to the earth, reacquaint itself with humility. Will I live to see the next chapter of my city?

It’s been interesting to follow the curve in mask wearing, sporadic in the beginning but almost universal now in my neighborhood, Manhattan’s East Village. We go about our business with faces covered like bandits in the old Westerns. A new tribal people bonded by our unstated agreement, glumly undertaken, to take this damn thing seriously.

In many parts of the country the mask is still seen as a kind of symbol of surrender to hysteria and hoax. In the early months here, denial issues were compounded by vanity. In our appearance-centered culture, few opted for self-effacement. Only defective ancients like myself thought hiding our faces was a good idea. At the pier, I sometimes encounter a phlegmy old gent who hangs out around the boathouse that once, in the days before Covid, dispatched kayaks into the Hudson. From beneath his dusty baseball cap, he aims disparaging looks at my K95. “Get rid of that thing. It’s not doing you any good.”

“It’s not doing me any harm either.”

End of dialogue.

Mostly, along the promontory, there is little talk about Covid. Or talk of any kind. In the presence of water and sky, one contemplates infection and death differently than one normally would. All the usual disaster details don’t crowd together in one’s mind. One has a hard time getting past the unfathomable nature of its enormity, its randomness. In the silence, one leans towards sitting with, rather than solving, dark mysteries.

Maybe part of the river’s pull is that it encourages avoidance. I recall in 2001 watching Tower One crumble without ever allowing myself the thought that inside its flaming belly there were people, hundreds, thousands of them, whose lives were being lost as I stood and stared dumbly at the catastrophe.

These days, neighbors, when we stop to talk, will ask me, “Did you have your first?” Like I’d been pregnant. A whole new code has come into being when the elderly meet and greet. We’ve devised our own unspoken way of saying, “We’ve survived. We’ve lived to see the day of the vaccines. We are the lucky ones.”

The news media is saying that by fall the city will be back to normal but it will not be the same. It’s been so long it’s hard to remember what ‘the same’ was like. Thanks to Pfizer, the fresh smells of the river that connect me with life rhythms that long predate my own will be permanently accessible to my maskless face, which I still cover when joggers approach. Will I return to Poets House that I once imagined I could never live without, and now barely think of? I am sure from time to time I will again enter that sanctuary of metered and unmetered expression. But it, like the city, will also not be the same.

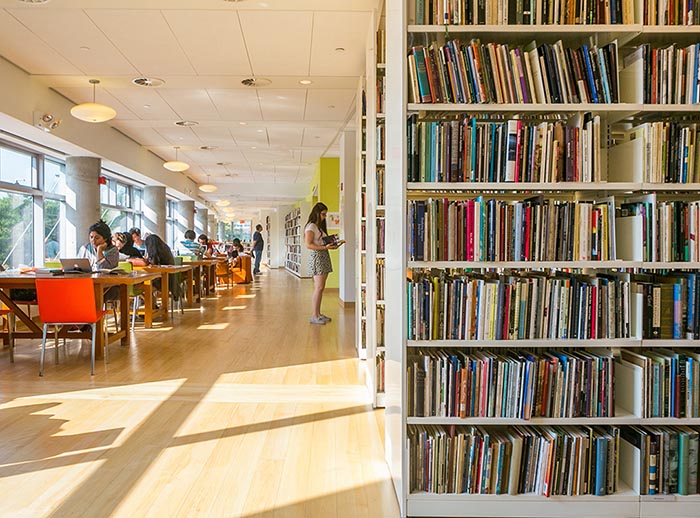

The Poets House [/] at 10 River Terrace, Manhattan, was set up in 1985 by the poet late Stanley Kunitz [/], two-time poet laureate of the United States. Free and open to the public, it has been called the ‘caretaker of the nation’s poetic heritage’ with a collection of more than 70,000 works and a host of recordings and videos of America’s major poets. Its present space, overlooking Battersea Park and the Hudson River, was beautifully designed by architect Louise Braverman [/]. In November 2020 it suspended operation due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Photographs: External view by Gryffindor via Wikimedia Commons. Reading room, courtesy Poetry House

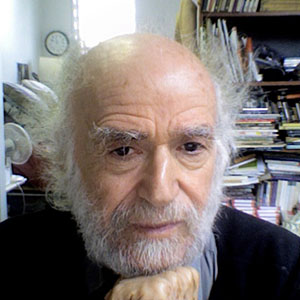

Robert Hirschfield is a New York-based free-lance writer and poet who has published many profiles of contemporary poets as well as stories on nonviolence activists in the Middle East, India, Nepal and the US. His work has appeared in Teachers & Writers Magazine, Tricycle, The Writer, The Jerusalem Report, Sojourners and other Publications.

For his previous article for Beshara Magazine on the poet and contemplative Robert Lax click here.

More News & Views

Don’t Take It Easy

Richard Gault is inspired by Michael Easter’s book The Comfort Crisis and explores the idea of ‘misogi’ during a 600-mile walk across Scotland

Book Review: ‘The Serviceberry’

Martha Cass contemplates the message of a new book by Robin Wall Kimmerer that advocates ‘an economy of gifts and abundance’

Book Review: ‘Conversations with Dostoevsky’

Andrew Watson engages with an innovative new book by George Pattison which explores Dostoevsky’s relevance in the contemporary world

Thich Nhat Hanh & the Poetry of Engaged Buddhism

Philip Brown presents the poem ‘Recommendation’ and comments on the potential of contemplative art to foster compassion

Introducing… ‘Perfect Days’ and ‘Nowhere Special’

Jane Clark watches two films with a contemplative theme

Book Review: ‘Irreducible: Consciousness, Life, Computers and Human Nature’

Richard Gault reviews a new book by Federico Faggin, one of the leading lights of the science of consciousness

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READERS’ COMMENTS

1 Comment

Submit a Comment

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

Thank you – a taste of humanity beautifully explored across the oceans.