News & Views

The Idea of the World

Richard Gault reviews Bernardo Kastrup’s recent book, which aims to re-instate consciousness as the fundamental principle of reality

Bernardo Kastrup is a man with a mission. His mission is to persuade us that the current scientific view of the world is wrong – seriously wrong. Reality is not what we have been told it is. It is not fundamentally made up of material stuff despite the apparent evidence of our senses and the work of scientists. No, reality is simply and only consciousness clothed in many and varied guises. Expressed more formally, Kastrup argues against the prevalent philosophy of materialism or physicalism and argues for the philosophy of idealism.

He comes well equipped and well qualified for his self-appointed mission. He has a PhD in Computer Engineering and has worked as a research scientist at CERN, so he knows the physicalist paradigm from the inside and in depth. From science he turned to philosophy and a second PhD for work on ontology and the philosophy of mind. This unique combination of knowledge and experience has led to many publications. The Idea of the World – subtitled ‘A multi-disciplinary argument for the mental nature of reality’ [1] – bundles together ten articles by him which have previously been published in academic journals spanning the fields of philosophy, neuroscience, psychology, psychiatry and physics between 2017 and 2018.

But even with all his intellectual resources and life experiences, it is no easy task that Kastrup has taken on. To succeed, he needs to overcome many obstacles and win many fights. The first of these is simply indifference. Who cares, for example, what the nature of the chair they sit on is? Whether it was made in China or came from IKEA, is plastic or wood, might be slightly relevant, but what the stuff that composes it ultimately is – atoms, quarks, superstrings or consciousness – is not a concern for most people.

Nevertheless, there is a small minority who do care and reflect on the deep questions which reality can appear to pose. Amongst these there are those who Kastrup will not need to persuade. Idealism as a philosophy has a long tradition stretching back to Plato; it may have withered but it has never entirely vanished. Many traditional spiritual beliefs, particularly the mystical ones, would find much to agree with in Kastrup’s book, I think.

So Kastrup focusses his attention on those who are interested in how the world works but do so assuming that it is made out of material and that explanations about it will be mechanistic. These are academic philosophers and scientists, particularly those whose work deals with fundamental questions about the structure of reality, about the mind and indeed about consciousness itself. If they can be convinced, then the radical transformation he is striving for will succeed. Ideas do filter out from universities to eventually become widely accepted and held to be common sense.

How can such scientists and philosophers be persuaded? Kastrup has recognised that he will only be listened to if he makes his arguments in a way which such people recognise as valid. He has to address them using their language and their own methodologies. How can he do this? The answer is, by having his work published in the very same academic journals in which his target audience present their own research findings. So for The Idea of the World, he has chosen only articles which have appeared in peer-reviewed academic journals, selecting those which are rated most highly within their respective discipline. By doing so, he shows that a broad range of scientists and thinkers are coming to acknowledge that there is merit in his argument that consciousness is the ground of all being. This in itself is an astonishing accomplishment. (For a short video in which he talks about his own journey to this point, see right or below.)

Video:

One and Three Chairs (1965), a conceptual art piece by Joseph Kosuth [/]. Image: via Wikimedia Commons

Why Reject Physicalism?

.

To persuade the sceptical, Kastrup attempts to do a number of things. He casts doubt on the prevailing belief in a material world, and demonstrates that an alternative way of understanding reality (everything is consciousness) is conceivable, offering evidence in support of this. He also explains why scientists and most people cling to materialism, even though it is demonstrably wrong, and finally he explains why we should make the effort to abandon a philosophy which in many ways has served us well for one which appears at variance with our normal experience.

Kastrup’s arguments actually rest on one small and simply expressed premise: experience is primary. That’s it. If we accept that all we know of the world is what we experience of it, then everything else must follow, according to him. And what follows is this: experience is not only primary, it is all there is.

In some ways, it is easy to accept that experience is primary. I know I am sitting on a chair because I feel it underneath me and can see it if I look at it. But immediately a questions arises: surely the reason I can experience it is because the chair is there to be experienced – there is a material chair supporting me and I can see it because light is bouncing off it into my eyes.

OK, Kastrup responds, let us consider this. You, the physicalist, say reality consists of two things – physical things (material objects and forces) and experiences; I, Kastrup, say there is only experience. In other words, there are two, alternative ways of understanding the world: one says the world is made up of matter (to be experienced) and mind (to experience); the other that there is only mind. Which of these is the better?

Kastrup goes to some lengths to acknowledge that the mind and matter ‘hypothesis’ does indeed accord with the most fundamental facts that we accept and science supports. For example, we all seem to live in the same world, there are laws of nature, there are direct correlations between a person’s experiences and measurable brain activity. But he also shows that the same facts are consistent with his hypothesis that there is only mind. He stresses that he is not arguing for solipsism – the idea that reality is simply what I have dreamed up. No, the reality I inhabit, I share with you. My mind did not create it and I cannot bend it to my will.

Given that we have two hypotheses, both of which explain the facts, which one should we choose? The well-established principle of Occam’s Razor [/] dictates that we pick the more parsimonious one, the one that requires fewer assumptions. Well, in this case I win, says Kastrup; I only need one ‘ontological primitive’ – namely, mind – whereas physicalists need two, mind and matter. Furthermore, by accepting that there is only mind, the notorious ‘hard problem of consciousness’ is dissolved. (See my previous article in Beshara Magazine for more on this). If there is a problem, it is not how does the material brain give rise to consciousness, but rather the converse: how, and indeed why, does mind give rise to the useful illusion of a material world?

A response by physicalists to the hard problem is a so-called ‘promissory’: although right now we do not know how material brains give rise to immaterial experiences, one day, following more research, we will. Kastrup’s response is to say: let’s suppose that you are correct: experiences are the product of brain activity. Then it should be expected that more experience would correlate with more brain activity, and conversely less brain activity with less experience.

Brain activity can be measured objectively and in general we can expect people to report their experiences truthfully. What is actually observed when brain activity is impaired, either by a trauma (brain injury), being close to somatic death, or the effects of psychedelics (which, contrary to what perhaps is commonly believed, do not stimulate the brain but subdue it)? All the evidence is that under all these different circumstances, subjects report heightened experiences – the very opposite of what a materialist theory would anticipate. Kastrup’s own theory, by contrast, does predict richer experiences when reduced brain function is impaired or reduced, as we will see.

Another problem eliminated is the one troubling panpsychists, ‘the subject combination problem’. Panpsychists acknowledge the reality of consciousness as something distinct from matter and propose that the smallest material things, such as atoms, do have a very limited consciousness. But atoms combine, and can combine to eventually form brains. A human subject’s sophisticated consciousness arises from the combination of many, much smaller consciousnesses, claim the panpsychists. But how? How can tiny consciousnesses merge to give a mind that can know art, music, science … ?

They cannot and do not, says Kastrup. The panpsychists’ error is to remain wedded to the idea that there is a reality to matter. They set consciousness within matter, but the truth is that matter, insofar as it has any meaning, is enclosed within consciousness. Panpsychism is fundamentally wrong – indeed a danger to a true understanding – as it threatens to perpetuate the materialist delusion.[2]

Beyond noting that physicists themselves acknowledge that objective, observer-independent properties do not exist, Kastrup does not extend much effort to exposing what might be called the ‘material weaknesses’ of materialism, namely, the continuing failure to find the ultimate material building blocks of matter. Of course there are ideas and competing theories (quarks, bosons, banes, superstrings …) but as he remarks:

I do not know that subatomic particles outside and independent of the mind exist with the same level of confidence that I do know that the chair I am sitting on, which I am directly acquainted with through conscious perception, exists. (p.27)

So rather than focusing further on materialism’s weakness, he devotes himself to explaining how his theory makes sense.

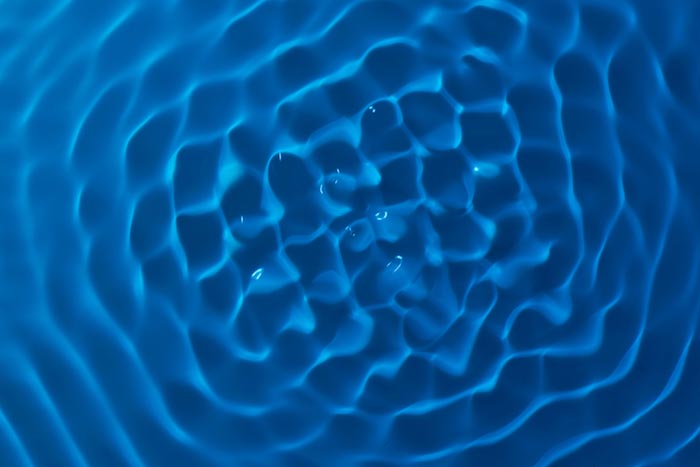

Chladni vibrations on water. Kastup maintains that the richness of the universe arises from universal consciousness in a manner analogous to the way a musical note produces beautiful patterns in sand or water. Image: Gregory Malevich/Shutterstock

Consciousness as the Only Reality

.

Kastrup’s theory is radically monistic. The one and only real thing is consciousness; it is this in which and through which we experience. And there is only the one consciousness – universal consciousness. Now this has been the message of mystics through the ages, but how is the hard-headed philosopher or scientist going to understand this?

That reality is just one consciousness flies in the face of two apparently obvious and related facts. Firstly, my consciousness feels like my own consciousness and does not seem to be a part of this purported universal consciousness. Secondly, it seems that everyone I meet, to say nothing of cats and dogs, also has their own consciousness. There appear to be many consciousnesses, not just one. How can Kastrup reconcile these facts with his theory?

He does so by drawing on mathematics, systems theory, quantum theory and psychiatry. While he is dismissive of the panpsychist notion that consciousnesses can combine, he holds that consciousness itself can divide. Basically he argues that the one universal consciousness has divided or ‘dissociated’ into many individual consciousnesses, such as yours and mine. That a consciousness can divide is attested by rare but well documented cases of it happening to individuals, so that the one body becomes home to multiple conscious and independent ‘alters’. An especially telling example of Dissociative Identity Disorder is that of a German woman who exhibited both seeing and blind alters. EEG analysis revealed that she really was blind when her blind alter was present. So if a human consciousness can dissociate, so in principle can the much greater universal consciousness, he argues.

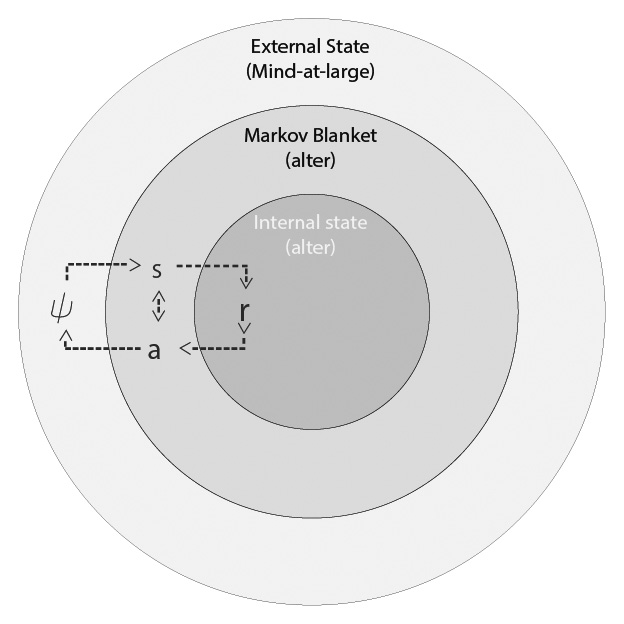

But if universal consciousness subdivides or dissociates, then each subdivision, or alter, necessarily has to be distinct and separate. To state the obvious, each alter requires a boundary, a demarcation, between its own interior consciousness and the outside which is everything else. Drawing on work in mathematics and systems theory, Kastrup identifies what features this boundary would have to have and concludes that it needs to be what systems theorists call a ‘Markov Blanket’.

The Markov Blanket. An alter – with an internal mental state r – interacts with its surrounding environment with the mental state Ψ – through the sensory (s) and active states (a) of its Markov Blanket. Image: The Ideal World, p.113

A Markov Blanket boundary must be permeable, meaning that it has to be possible for information to be exchanged between the dissociated alter’s consciousness and the external consciousness of ‘mind-at-large’. However, it needs to be much more than a clear window. The Markov Blanket has to actively filter what mind-at-large presents to an alter. It then has to re-present what is presented in a form which the consciousness of the alter can comprehend. What is more, it needs to able to comprehend safely. It is the crucial feature of a Markov Boundary that it has to shield the inner consciousness from the outer world by veiling it.

As Kastrup tells us, systems theorists and mathematicians have discovered that:

a hypothetical organism with perfect perception – that is, able to perfectly mirror the qualities of the surrounding external world in its internal states […] would dissolve into an entropic soup. To survive, organisms must […] represent the outside world in a compressed, coded form. (p.79)

This is the essential role of the Markov Blanket; it is the buffer between each of our individual dissociated consciousnesses and mind at large. Without its veil we would cease to exist. More familiarly, we can think of the Markov Blanket as comprising all our organs of perception and communication. Together these give us all we experience outside our (inner) consciousness. Kastrup therefore maintains that what we take to be the ‘physical world is the Markov Blanket. Everything else… is non-physical thought.’ (p.116). The chair I am sitting on is my Markov Blanket’s representation of the idea of this chair in the consciousness of mind-at-large.

These theoretical insights have been given support by the experimental work of Donald Hoffmann. He has shown that what we perceive is not reality as such. Rather our senses appear designed to recognise what is useful for survival rather than aiming to uncover truth, or as Hoffmann himself pithily summarises: ‘Perception is not about truth, it’s about having kids’.[3] Hoffmann has demonstrated that if an organism were able to see things as they truly are, it would be doomed: ‘… natural selection drives true perceptions to swift extinction’.[4]

But what about cases where the Markov Blanket is weakened, so that reality enters consciousness subject to less compression, less coding? Then people should experience more of reality, have a richer experience. And as we have already mentioned, Kastrup demonstrates that this is exactly what people with brain damage, those who have suffered a near death experience or those affected by psychedelics, report. Furthermore, when the Markov Blanket fails completely at death, dissociation necessarily ends. There can then be ‘… a reintegration of memory, identity and emotion lost at birth… an expansion of our felt sense of identity… enrichment of our emotional inner life’. (p.275)

The process by which universal consciousness could appear in my alter consciousness as nature or chairs or people Kastrup explains in terms of quantum field theory. He sees a correspondence between what physicists call the quantum field and what he names as mind. Where physicists think the physical world can ultimately be explained as ‘excitations of the quantum field’, he states that ‘it is equally valid to think of the dynamics of nature as being constituted by the excitations of universal mind’ (p.107). An alter’s mind also produces ‘excitations’ and it is the interaction of these two sets of excitations – an interference pattern – that yield the representation of a physical chair or whatever. These excitations can also appear to us as laws of physics, logic and mathematics.

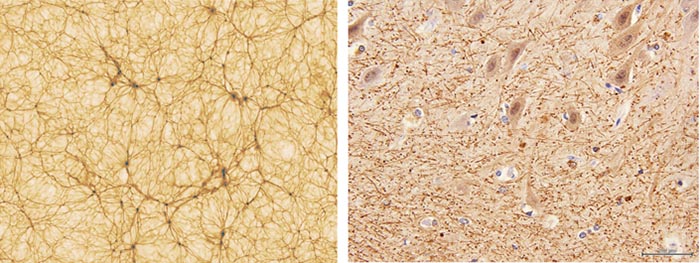

Kastrup’s argument is that it is not the case that brain activity gives rise to our consciousness with its thoughts and perceptions, but that our thoughts and perceptions give rise to brain activity. The brain is but the Markov Blanket’s mediated impression of an individual’s consciousness, just as Kant’s ‘starry sky above’ is a face of universal consciousness. Indeed, Kastrup believes that ‘… the entire physical universe may be akin to a nervous system’(p. 65). Coincidence or not, there are remarkably close ‘unexplained structural similarities … between the universe at its largest scales and biological brains’ (p. 65).

The Question of Meaning

.

Kastrup’s primary aim is to make the case that consciousness is the ‘ontological primitive’. But if we accept this, then clearly many questions arise. It would be beyond the scope of any one book to give all the answers but Kastrup does make a start.

An obvious question is why would universal consciousness dissociate? Or in simple terms, why bother to create us and the world we seem to inhabit? The answer that Kastrup gives is that doing so enhances experience for universal consciousness itself. Universal consciousness without dissociated alters is a consciousness which can only experience thought. Perception can only occur when there is something apparently other to be perceived. So by dissociating, universal consciousness enriches experience by supplementing thought with perception.

Of course there are more fundamental questions, such as what gave rise to universal consciousness. These are in principle unanswerable, Kastrup argues. Why? Because answers can only be given within a framework of space–time but this framework itself is a construct, a ‘kind of illusion’, so that ‘whatever reality precedes spacetime ontologically is unreachable by the human intellect’. (p. 253) So he believes that we are denied ultimate truths, but this is not a counsel of despair. The ‘penultimate truths’ we can access ‘… tell us something indirectly true about what reality is and how it works’ (p.254). This means that by his own admission, all that Kastrup tells us is at best indirectly true. Nevertheless, he maintains that it is closer to truth than the physicalists’ account.

So if idealism is closer to truth, why has materialism prevailed? And if it is not the full truth, should the average person continue to sit on their chair unconcerned whether it might be made out of plastic, atoms or consciousness? These two questions turn out to be connected because both are answered by focussing on meaning – or rather its absence.

Under the physicalist view of the world, things themselves have no intrinsic meaning. A chair is a chair. It does have an extrinsic meaning – it is meant to be sat on – but this is a meaning we have given it. Poets and lovers may evoke meanings in roses or sunsets, but such meanings are the products of their subjective imaginations or fantasies, not anything the rose or sunset has given to them. The world is essentially meaningless, though in the post-modern era meanings can be arbitrarily (and ultimately unsatisfyingly) assigned.

But life without real meaning is – well, meaningless. To overcome or bear this essential ennui, Kastrup argues that the intellectual elite have found comfort in the physicalist narrative. It ‘… provides a foundation for rationalising the choice of living an unexamined, superficial life’ (p.211). Research scientists can find self-esteem in their work and meaning in thinking their discoveries will immortalise them, for example. Kastrup cites studies which have shown that coming to terms with death in a meaningless world also leads to a search for ‘closure’. CERN’s Large Hadron Collider he sees as a:

multibillion dollar experiment […] whose primary purpose is to ‘close’ the Standard Model of particle physics […] an unprecedented effort to produce a causally complete unambiguous model of reality [… It] reflects the elites’ ego’s attempt to regain, through heightened closure, the meaning it lost along with religion. (p.217)

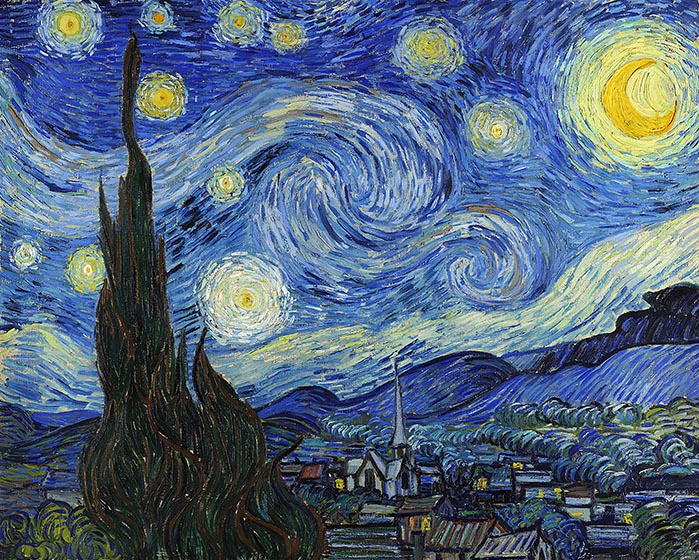

The Starry Night by Vincent Van Gogh. An example of what the world looks like when our Markov Blanket begins to reduce in effectiveness. Image: GL Archive [/] / Alamy Stock Photo

The Re-enchantment of the World

.

But for those who are not of the elite, who sit on chairs unaware of or uninterested in scientific breakthroughs, multibillion experiments do not restore meaning to life. So what can? Kastrup’s answer is: the world itself. Once consciousness is accepted as the foundation of everything, then it can be understood that ‘the world is amenable to hermeneutics: it means something beyond its face-value appearances.’ There are meanings in the world which are not ‘mere personal projections, but actual properties of the world’ (p.233).

So one of the most valuable fruits of the alternative which Kastrup offers is a re-enchantment of the world, which would be of benefit to every chair-sitter. Another virtue is that his ideas (re-) legitimise the teachings of the spiritual traditions, to which he is not afraid to refer, finding parallels between his alternative and paths such as Taoism, the Hermetic tradition, ‘ancient Islamic mysticism’, Advaita Vedanta and medieval scholastics (pp.234–6).

However, whilst those who subscribe to a traditional spiritual belief can find novel, additional support for their views in Kastrup’s work, their understanding of God and Kastrup’s are likely very different. For him, Universal Consciousness ‘is what it is’ and little more. It is unlikely to be especially aware of us nor engage in thought as we do.[5] Simple self-excitation within it was enough to bring about the richness of the universe in a manner analogous to the way a Chladni Plate reveals beautiful patterns of sand moved by a single musical note (p.242). There is no notion that this consciousness embodies compassion and love, or the possibility of the kind of intimate contact which is the very essence of the mystical traditions. There is work to be done if this rather spartan image of God is to be reconciled even with his own stress on seeing meaning in nature.

Conclusion

.

The Copernican revolution heralded a profound change in the way the world and the universe were seen. What Kastrup seeks to achieve is if anything more radical. But finely argued as this book is, how likely is it that the case for consciousness will ultimately be widely and generally accepted?

Well, look at it this way. We and the world must be made of something. If the choice is quarks or consciousness, which should be chosen? Nobody has ever seen a quark but everyone has intimate experience of consciousness.

And everybody dreams. We dream and in our dreams, landscapes appear filled with buildings, rooms, trees, people… We walk in our dreams, touch a lover, smell a rose perhaps, and the ground does not give way under our feet. When we awake we realise, that was a dream – those were not solid buildings, not real people; the ‘space’ they filled was not space but simply an illusion which occupied no space at all inside our head. True, but while we slept we did not question the dream world’s validity: everything we experienced seemed real at the time. So we know that consciousness can appear in phenomenal form. [6]

In terms of the overall impact of the book: there is much to be said for a mission that sets out to rescue us from the emptiness and confusion of post-modernism – a mission which if successful could also contribute to the tasks of solving global problems. Kastrup puts it well at the end: ‘Contemporary culture is forgetting to read the letter for the sake of describing the envelope’ (p.237). We should be grateful to him for the way he shows that the world should be regarded as an envelope; it is up to us, not him, to read the letter.

The Idea of the World: A multi-disciplinary argument for the mental nature of reality (2019) was published by Iff Books in 2019.

You can learn more about Bernardo Kastrup on his website www.bernardokastrup.com. Here you can read his writings and essays as well as links to interviews with him. The extraordinary story of how he moved from computer engineering to the ideas described here are recounted in his earlier book, More the Allegory (Iff Books, 2016). His latest book is Decoding Schopenhauer’s Metaphysics: The key to understanding how it solves the hard problem of consciousness and the paradoxes of quantum mechanics (Iff Books, 2020).

Dr Richard Gault has worked at universities in Scotland, Ireland, Holland and Germany, where he has taught and researched a variety of subjects, including the history and philosophy of science and technology

More News & Views

Don’t Take It Easy

Richard Gault is inspired by Michael Easter’s book The Comfort Crisis and explores the idea of ‘misogi’ during a 600-mile walk across Scotland

Book Review: ‘The Serviceberry’

Martha Cass contemplates the message of a new book by Robin Wall Kimmerer that advocates ‘an economy of gifts and abundance’

Book Review: ‘Conversations with Dostoevsky’

Andrew Watson engages with an innovative new book by George Pattison which explores Dostoevsky’s relevance in the contemporary world

Thich Nhat Hanh & the Poetry of Engaged Buddhism

Philip Brown presents the poem ‘Recommendation’ and comments on the potential of contemplative art to foster compassion

Introducing… ‘Perfect Days’ and ‘Nowhere Special’

Jane Clark watches two films with a contemplative theme

Book Review: ‘Irreducible: Consciousness, Life, Computers and Human Nature’

Richard Gault reviews a new book by Federico Faggin, one of the leading lights of the science of consciousness

Video:

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

Sources (click to open)

Images

Banner image: Bernardo Kastrup. Photograph: You Tube [/]

Others

[1] BERNARDO KASTRUP, The Idea of the World: A multi-disciplinary argument for the mental nature of reality’ (Iff Books, 2019)

[2] For more on this, see Kastrup’s own web-site www.bernardokastrup.com

[3] DONALD HOFFMAN, The Case Against Reality: How Evolution Hid the Truth from Our Eyes, (W.W. Norton & Company, 2019), p.77

[4] HOFFMAN, p.57

[5] Kastrup speaking on Patterson in Pursuit, Episode 98 (1 September 2019), particularly the ten minutes starting around 25.00 minutes. Click here [/]

[6] See also BERNARDO KASTRUP, More the Allegory (Iff Books, 2016) Part III, particularly p. 189.

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READERS’ COMMENTS

17 Comments

Submit a Comment

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

Consciousness is very important, but the unconscious is even more.

Matter comes out from an unnatural source it is an illusion.

Most of the universe, creation is made out of emptiness because atoms themselves are 99.9% empty.

Is there such thing as ‘the unconscious’? Kastrup argues there is not, that ‘it may at root be a linguistic fallacy’ (p.154).

He distinguishes three types or states of consciousness: (a) non-conscious (unexperienced); (b) conscious (experienced); and (c) meta-conscious (re-represented) (pp.155-6). For example, until I draw your attention to it, you probably have not been aware of (i.e. have not experienced) blinking or breathing in the past minutes. Now that I have mentioned them, blinking and breathing are experienced. The associated type of consciousness has switched from (a) to (b). ‘Linguistically’ type (a) is commonly labelled ‘unconscious’ but it is better understood as consciousness you have chosen not to experience or cannot reflect on. If you go further and think about your blinking or breathing then you engage in the highest form of consciousness – thought (c).

In the case of non-conscious blinking or breathing it is easy to access the non-conscious action, as I just showed. But there may be a more fundamental non-consciousness which is very difficult to reach. Depth psychology (e.g. Jungian) is based on helping a person understand how hidden memories and experiences affect their conscious (b & c) life. While depth psychologists refer to the (usually) inaccessible realm as ‘the unconscious’ this is a misnomer. What they mean is that it is a consciousness not normally available to be experienced (b) or thought about (c), i.e. it is (a). If it were truly unconscious then depth psychologists would be out of a job.

Actually, Bernardo used to use the word “unconscious.” I met him online (on his now defunct website forum) in 2013 and he was using it in the Jungian sense.

I wrote him and said if all is consciousness there can’t be anything “unconscious” or you’re sliding back into materialist notions.

I suggested Sri Aurobindo’s distinctions of superconscious and subconscious and he seems to have at least taken in the latter.

Excellent review, by the way. I think in terms of critiquing materialism/physicalism, nobody today is doing a better job than Bernardo – at least, nobody well known (Michel Bitbol has some truly inspired writings on this).

As far as an alternative, Bernardo has acknowledged there is a “top down” panpsychism which seems BOTH mind and matter as reflections of a greater consciousness, and by “matter” does not mean anything resembling the dead meaningless stuff of materialism.

But his “Mind At Large” which seems oddly semi-conscious (it includes phenomenal consciousness similar to that in animals and metacognition, which is basically you thinking about what you’re reading and thinking) is just not going to catch on. I think it is the biggest obstacle to his view being accepted because it is just so obviously contradictory and ultimately incoherent.

It’s a shame, and I’m guessing what’s going to happen is someone is going ot come along and adapt his physicalist critique and connect it to a far more comprehensive understanding of Consciousness. Iain McGilchrist is helpful in this regard, but at the moment, I don’t see anyone who has presented a fuller, more comprehensive view than Sri Aurobindo.

I thoroughly enjoyed this article.

The paragraph, “An obvious question is why would universal consciousness dissociate? Or in simple terms, why bother to create us and the world we seem to inhabit? The answer that Kastrup gives is that doing so enhances experience for universal consciousness itself. Universal consciousness without dissociated alters is a consciousness which can only experience thought. Perception can only occur when there is something apparently other to be perceived. So by dissociating, universal consciousness enriches experience by supplementing thought with perception.” seems a perfect parallel to the first sentence in ibnArabi’s “Fusus al Hikam”, which only reinforces Dr. Kastorp’s thesis.

Students of Ibn Arabi can find other correspondences with Kastrup’s theory, for example, the Markov Blanket and the role of veils in Arabi’s metaphysics. Though. as noted, Kastrup acknowledges parallels with ‘ancient Islamic mysticism’ he does not explore them in any detail. He limits himself to citing Henry Corbin as quoted by other authors.

I think of consciousness as something like running, which only happens when an animal with legs moves faster than walking; it certainly doesn’t create animals. Reifying gerundives is what thinking does, so perhaps it is thinking that creates its own reality? I’m afraid I find the idea that consciousness would be bored unless it dissociated rather ludicrous and it did worry me that the only illustration of dissociation that Kestrup provided was taken from psychopathology. He could have talked about the much healthier word Ubuntu, which celebrates relationship and gives subject and other equal status, or David Bohm”s “Implicate Order” which is also even-handed and convivial. I guess Kastrup would like to persuade his fellow scientists that there are other criteria for the discovery of the Universal Theory than the scientific method but is hoist on his own idealist petard. I am grateful to him for making me more certain that personal commitment to bodily existence is more rewarding than deifying consciousness.

Examples of people suffering Dissociative Identity Disorder are given by Kastrup as evidence that consciousness can divide, not simply as an illustration of the phenomenon. As he himself sees it, you and everybody else also (and tellingly) ‘illustrate’ dissociation of the one, universal consciousness. The problem Kastrup is trying to solve seems to me to be very different to the one for which ubuntu is the answer. The latter is a political/social philosophy while Kastrup’s search is an ontological one. He necessarily, I think, does stray into cosmology but however related, cosmology and ontology can be distinguished. It would be possible to find agreement with him that consciousness is the ontological primitive while still disputing his suggestion for universal consciousness’s initial motive.

What can anyone mean by “matter” or something “physical” outside experience?

I just had a conversation with a professor of philosophy in a Facebook group. I’ve been asking the people there for a year now what they mean by the word “physical”. NOBODY has been able to come close to saying what it means.

I’ve asked philosophers and scientists for 50 years and there simply is nothing close to an understanding of the word.

That is because there is no meaning to it (I hope you know the difference between the phenomenological – ie experiential – meaning of “physical’ and the abstract concept of physical as used by philosophers and physicists). What “physical” means is simple:

“I have no idea what the basis of reality is, no evidence for anything purely “physical” but I know for certain – by dogmatic emotionally based and rather hysterical belief – that the ultimate reality is dead, stupid, meaningless and pointless.” In other words, physicalism is a statement of absolute faith in pure nihilism.

Now, I am amused to find how often people come back and say, “Try standing in front of a train and see how imaginary anything “physical” is.”

They don’t realize they’ve just appealed to experience to prove there’s really no such thing as experience.

How personally persuasive do you find Kastrup’s arguments Richard? I have followed Bernardo’s work quite a bit and he seems to have injected life into Idealism which has largely been ignored by modern mainstream philosophy, which seems to take the approach that idealism is self-evidentially stupid. But it seems to me that mainstream philosophy simply ignores a whole class of phenomena (unsatisfactorily labelled as “paranormal”) which idealism in one form or another would seem to be much better able to accommodate. I am not sure of Bernardo’s views on this as he seems to largely avoid this topic (maybe to avoid a “new age” type tag and the baggage that brings?).

In ‘The Idea of the World’ itself Kastrup specifically and deliberately aims to persuade using the methodology of analytic philosophy to appeal to the intellect of western scientists and academics. His arguments are persuasive enough to have been accepted by peer-reviewed academic journals. However, there are other ways of understanding reality as arising from ‘consciousness’, such as those he mentions and I cited (Taoism, the Hermetic tradition, ‘ancient Islamic mysticism’, Advaita Vedanta and medieval scholastics). Kastrup also describes in some detail the remarkable cosmologies of Aboriginal Australians and Amazonian Indians in his book ‘More than Allegory’. However much such ‘myths’ (a term Kastrup carefully defines as not meaning false) differ, all teach that the material realm is but a part of the story and not the most significant at that. Subscribing to such myths is not a product of analytical reason.

I think the work of Rupert Sheldrake, who does investigate ‘paranormal’ phenomena, is supported by Kastrup’s theories. But, as you suggest, to persuade the sceptic it’s probably wise not to be seen to be tainted by new age ideas.

It seems to me that the stigma around really interesting areas such as Sheldrake’s purported “morphic resonance” is a real shame. There is so much interesting stuff out there that is dismissed as “woo” but it seems that the only way that physicalism remains as a tenable philosophy is by that very dismissal.

“You, the physicalist, say reality consists of two things – physical things (material objects and forces) and experiences”.

Says who? Many would argue that, more simply, reality consists of physical things, and that experiences are part of such a physical reality.

Also, this article feels like a sales pitch. it doesn’t challenge Kastrup at all. It almost implies that he is right, and his real mission is to now convert the ignorant world (most academics included) to “the truth”. In fact, the burden of proof is 100% on him. If he had proven his ideas they would now be widely accepted.

You are right, there are plenty of academics and scientists who would say that ‘reality consists of physical things’. The problem is, how can consciousness fit in such a reality? One response is to deny that there is such a thing as consciousness. This view, whose foremost champion is Daniel Dennett, is not widely accepted, indeed it is far more widely ridiculed. More commonly consciousness is recognised but is said to be an ‘emergent property’, a product of a physical, material thing (the brain). The problem is (this is the so-called ‘Hard Problem’) nobody has been able to explain how consciousness could arise from something material. This in turn leads to two possible positions: (a) while admitting that currently the Hard Problem cannot be solved, betting on science one day in the future managing to do so; or (b) accepting that alongside material things, there is a separate category, consciousness.

Position (a) then means continuing to hold that reality is solely physical. Kastrup himself admits that he can’t prove that (a) is wrong (p.65) because, of course, he cannot see the future. But if we stick to the present and known facts then it seems right to acknowledge consciousness as real and distinct. This position is the one Kastrup deals with (‘You say reality consists of two things …’) .

As it is, scientists exploring ‘physical’ reality at the quantum level, have not found solid, objective, material things there.

Kastrup cannot be dismissed because he is not ‘widely accepted’. Truth is not subject to a democratic vote. The history of science is one of new ideas gradually becoming recognised as valid. Initially there is necessarily resistance, as Thomas Kuhn explained in his landmark work ‘The Structure of Scientific Revolutions’. Kastrup himself offers a novel psychological explanation for scientific support for physicalism. Note too, that even if not widely accepted, Kastrup’s ideas have been acknowledged as having merit by being published in peer-reviewed academic and scientific journals.

Seems a tad unfair Peter. It doesn’t appear this piece is supposed to be a critique, rather an introduction and summary of Kastrup’s ideas (which I think it does very well). As to the idea that Kastrup’s ideas would be widely accepted by now by academic philosophy; I don’t think it works that way: entrenched positions in academia take eons to change (these debates have raging for three millennia plus). There are signs that some philosophers are moving, if not to full idealism then to a kind of “half-way house” of panpsychism (e.g . Galen Strawson, David Chalmers et al.). To Kastrup’s credit he is not shy of debating and will defend his position against any people who want to engage him.

The burden of proof is entirely on the physicalist.

By definition (even Sam Harris admits this!) nobody can ever ever know anything, have even one scintilla of evidence, regarding the existence of something purely physical.

There is no need for that concept, there is no evidence for it, and the only possible reason to hold the believe in physicalism is pure prejudice.

Try defining it (without ANY reference to the phenomenological experience of physical things). you can’t do it. If you think you can, read Freya Matthews and Barbara Montero first (Montero is more mainstream so you might start with her)

The extent of confusion about physicalism is astonishing. It is meaningless. There can’t possibly even BE such a thing as purely physical “stuff.” because physicists derive virtually ALL of their knowledge of physical “whatever it is” by measuring sense experience.

Basically, what you’re saying when you declare something physical to be the basis of the universe is you’re saying that quantitative, mathematical concepts derived from sense data by physicists are the basis of the universe.

When you put it that way, can you see how incoherent the idea is?

If Peter is still here, I wonder if he could address directly Bernardo’s first principle:

If all we know is experience, it’s the physicalist who is positing the existence of something unprovable. Give us a reason why we should believe in the physicalist faith, if there is no evidence for it?

My comment was declared as SPAM sans any ground!!!