News & Views

Reflections: Staying –

A Lesson from Lockdown

Andrew Watson finds guidance in the wisdom of the Desert Fathers (and Mothers) during the Covid-19 pandemic

Street sign in Nottingham UK, April 14th 2020, in the midst of the lockdown. Photograph: Martyn Williams / Alamy Stock Photo

In March 2020 the music stopped in the UK, and we all had to stay where we were. Many of us had scarcely registered the threat from the coronavirus before it had paralysed almost every aspect of our existence. The boundaries of our world contracted in a matter of days, and for many weeks our dispersed lives were concentrated into a single defined space, outside of which we could move only for short and strictly prescribed purposes. Even as the restrictions have been lifted – at least temporarily – the variety of incident and encounter that had previously defined the way we live has been dramatically reduced, and most of us have found ourselves in conditions of stillness and inactivity we had never known before, nor even imagined. Our lives have become simpler and more predictable even as the future has become increasingly uncertain.

In political and economic terms, the pandemic has clearly been a calamity for the world, the full extent of which we have yet to learn. But at the individual level, the restriction of our movements has been experienced in a variety of ways. There has been resentment, anxiety and boredom, but also an opportunity to stop and consider our life from a different perspective. Certain truths that have long been ignored or overlooked have been forced into our awareness, whether welcome or not. Essential to this is the lack of distraction, which makes us slow down and notice the ordinary and everyday things that underpin our existence, such as the people we live with in the same household or in the neighbourhood, and the natural life that has continued around us unaffected – indeed emboldened – by the lockdown. In particular, we have been forced to reassess the way we relate to our own selves when there is little to take our attention elsewhere.

Emboldened deer on the Harold Hill housing estate in Romford, Britain, April 3, 2020. Photograph: REUTERS/Peter Cziborra

The Challenge of Staying

.

Of course in many households this has not been at all a time of peace or tranquility – unbroken contact with family members permits hidden tensions to grow, and some relationships have come apart in the excess of contact. But whatever the result, the lockdown has given an opportunity for seeing what is actually present, and with that has come the possibility of growth.

For myself, the change has perhaps been greater than for most, having lived a life characterised by movement and change, with an essential restlessness colouring much of what I have done. I acquired the habit of movement early: by the age of ten I had lived in five different countries, and after their divorce my parents lived in different countries from each other. My first day of primary school was spent trying to decipher a language I had no knowledge of. In the years since I have never stayed in the same home for more than a year or two, and even then most weeks would involve some trip or journey, often simply for the sake of change.

In earlier years I explained this to myself as the path of the seeker, in search of an existence distinguished from the ordinary by greater intensity and variety, because these things suggested greater abundance of life. But over time the expected rewards have not been forthcoming. One aspect of my mindset has been a detached relationship with the idea of ‘home’, which has remained stubbornly elusive. The closest I had to a childhood home was in my mother’s house in Surrey, where I had lived for only a year before I went to a boarding school in London when I was 11. In the following years it has not been a place I lingered, and visits often tended to be brief and dutiful.

This year, however, fate decreed otherwise. I happened to have moved from my apartment in Greece to my mother’s house in February, to help out while she underwent major surgery on her knee. When the operation was cancelled and the lockdown imposed on the same day in March, I ended up staying for many months, awaiting the surgery that would restore her mobility (and mine). It is not what I would have chosen, at least consciously, but it has turned out to have been a godsend. And I am still here.

The Monastery of St Anthony in the East Egyptian desert, founded by followers of St Anthony on the site of his hermit’s cell in about 300ce. Now a Coptic Orthodox centre, it is said to be the oldest monastery in the world. Photograph: Tony Moran/Shutterstock

The Wisdom of the Desert Fathers

.

By chance, near the beginning of the lockdown I came across a book about the Desert Fathers – those seekers of God, men and women, who retreated into the deserts of Egypt and Palestine in the first centuries of the Christian era. They have been my companions throughout these weeks of confinement. They recorded their thoughts in plain unadorned language that resembled the austerity of their own lives, but even at this great distance in time they have much to tell us. Though their initial action was one of displacement – withdrawal from the city into the desert – the emphasis of their words is always on the necessity of staying, of remaining in a single defined place and dedicating themselves to it, and to their community, without qualification. One anonymous hermit advised the seeker:

Go, sit in your cell, and give your body in pledge to the walls of your cell, and do not come out of it. Let your imagination think what it likes, only do not let your body leave the cell’.[1]

The implication is that the staying is integral to the searching.

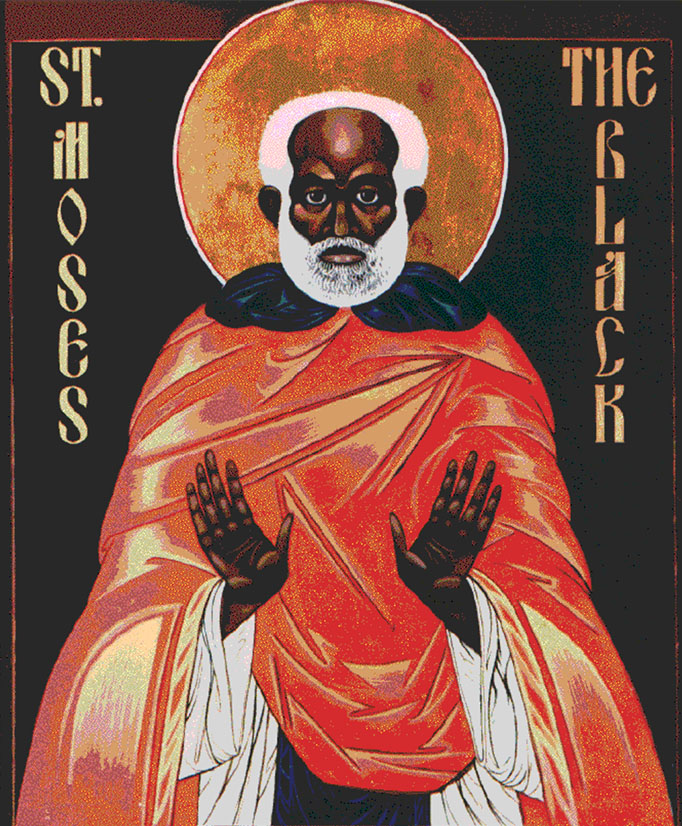

The fourth-century monk Abba Moses (known as Moses the Black) advised his pupils: ‘Sit in your cell and your cell will teach you everything’.[2] This addresses, I came to realise, an essential incoherence in my belief, developed over many years, that there is an ideal location for the spiritual life – another more auspicious place just over the horizon compared to which the present one is inadequate. This is not to say that any move to somewhere more suitable is illegitimate, or indeed that travel is not a valid way to gain knowledge and insight. But a habitual moving away from the reality in front of us towards an unreal notion of perfection carries within it the seeds of failure, As another (anonymous) desert hermit said: “Warfare is everywhere.” [3]

Whenever we say to ourselves that life is intolerable in this place, and another and better one must be sought where these frustrations and restrictions are not present, we do something fraught with danger. We begin to impose our own terms on life, and only allow it to come to us in ways we deem acceptable. Slowly, over time, if we continue in this way, our essential link with reality becomes more and more tenuous, and eventually it can peter out into a desert of concepts and dreams.

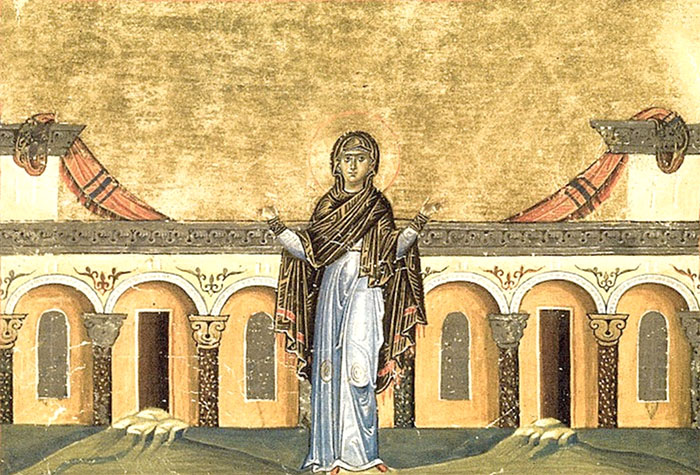

One of the Desert Mothers, Amma Syncletica of Alexandria, addresses the same essential question in the fourth century:

If you are living in a monastic community, do not go to another place: it will do you a great deal of harm. If a bird abandons the eggs she has been sitting on, she prevents them hatching; and in the same way the monk or nun will grow cold and their faith will perish if they go around from one place to another.[4]

The fourth century Desert Mother, St Syncliticia of Alexandria, whose sayings were recorded in The Sayings of the Desert Fathers. Image: miniature dated 985 ce, by Minology of Vasily II, now in the Vatican Library, Rome. Via Wikimedia Commons

Attending to Reality

.

On a global level, it is highly likely that the pandemic will exacerbate the general instability and division that is already on the rise. For me, however, it has come as an opportunity to confront the instability and division that I have been carrying within myself. In this new act of facing, the crucial element is stability: the simple fact of staying still and listening. The great father of desert monasticism, St Antony the Great, wrote in the fourth century:

Now the Greeks leave home and traverse the sea to gain an education but there is no need for us to go abroad on account of the Kingdom of Heaven nor to cross the sea for virtue. For the Lord has told us before, ‘The Kingdom of God is within you’. The only thing goodness needs, then, is that which is within the human mind.’ [5]

St Benedict, the father of western monasticism, who lived around the same time as the Desert Fathers, also emphasises the central importance of stability to any real spiritual life. He contrasts it with the practice of wandering monks, or gyrovagues, who, he says, are ‘always on the move, with no stability, indulging their own wills’.[6] In his view, the hearts of such men are pulled here and there, this way and that, by countless desires for created things that have only this in common: none of them is God, none of them is the truth. The groundrock of the spiritual life must be reality, and reality is everywhere. The Desert Fathers repeatedly assert that what God arranges for us to experience at each moment is the best and holiest thing that could happen to us. For reality is what we most seek to escape, and yet most ardently long for. What needs to change is the way in which we receive it.

Such insights have made me aware of the need to simply attend to where I am, as though there were nowhere else I could be. During the lockdown, I have explored areas of the local countryside I had never seen before, and discovered beauty and variety I knew nothing about, despite the many years that I have been coming here. I began for the first time to watch the birds in the garden, to gain an understanding of their lives and even to help them in small ways. To fill the long hours of leisure I have found maintenance jobs to do, painting walls and mending fences, doing general repairs, tending the flower beds, planting a herb garden. Like millions of others, I experimented with new recipes and began to bake bread and cakes. I even had a go at croissants, though that proved to be a step too far!

Meanwhile the combination of the virus and her physical condition have made my mother unusually vulnerable and dependent, placing me in a relatively unfamiliar position of care and responsibility. These simple tasks of care and stewardship – of seeing what needs to be done each day and trying to do it – seem to be what we are called upon to perform more generally in life. The world is not a place to pass through and make use of only for our own ends, but rather one that asks constantly for our engagement and protection.

Walker on the South Downs path in Surrey. One of the unexpected results of the lockdown has been the increased number of people and families walking the national trails. Photograph: Get Surrey [/]

Preparing for the Future

.

For many people these observations will be nothing new, but to me they have come as a lesson I needed to learn, and the lockdown has provided the means for that education to take place. It has brought home to me the truth that a life that can be regarded as spiritual is lived right here, right now, in accordance with whatever the place in front of us and the context gives us to do. St Euthymius the Great, a fifth-century abbot in the desert in Palestine, wrote:

If someone tries to do something good in the place where he lives but fails to complete it, he should not think that he will accomplish it elsewhere. It is not the place that produces success, but faith and a firm will. A tree which is often transplanted does not bear fruit.[7]

What all these monks are addressing across the centuries is the hyper-modern yet ageless temptation to move on, to try to reinvent ourselves, to construct lifestyles and identities that are the products of our imaginations rather than arising out of true openness to the world around us. So often we seek to impose a constructed self – one that flatters the idea we would like to have of ourselves – rather than allowing a more authentic self to reveal itself slowly over time. These projects of self-invention, however, gradually (never immediately) become brittle and sterile, because they are not rooted in the reality of who we are, which we cannot impose; we can only allow it to reveal itself in its own way.

As old frustrations and complaints returned to the surface in the first weeks of the lockdown. I often felt the familiar urge to move, to find another place. Yet gradually the commitment, sustained at first by necessity, to the present rather than the future, to here rather than there, has revealed more and more of what is real everywhere.

Thus for me the lockdown has given a rare opportunity for a type of growth I was instinctively averse to. I also suspect that it is offered as a preparation for further trials that the pandemic will bring in its wake. This crisis (a Greek word that means ‘judgment’) brought by the virus is by no means over yet, and difficult days may await us in many aspects of our lives. It is likely that our stability and resilience will be tested further in the coming months.

Andrew Watson is a writer and translator presently living in the UK

More News & Views

Don’t Take It Easy

Richard Gault is inspired by Michael Easter’s book The Comfort Crisis and explores the idea of ‘misogi’ during a 600-mile walk across Scotland

Book Review: ‘The Serviceberry’

Martha Cass contemplates the message of a new book by Robin Wall Kimmerer that advocates ‘an economy of gifts and abundance’

Book Review: ‘Conversations with Dostoevsky’

Andrew Watson engages with an innovative new book by George Pattison which explores Dostoevsky’s relevance in the contemporary world

Thich Nhat Hanh & the Poetry of Engaged Buddhism

Philip Brown presents the poem ‘Recommendation’ and comments on the potential of contemplative art to foster compassion

Introducing… ‘Perfect Days’ and ‘Nowhere Special’

Jane Clark watches two films with a contemplative theme

Book Review: ‘Irreducible: Consciousness, Life, Computers and Human Nature’

Richard Gault reviews a new book by Federico Faggin, one of the leading lights of the science of consciousness

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

Sources (click to open)

Images

Inset: Abba Moses, also known as Moses the Black, a fourth century monk and priest from Ethiopia. He said to have converted from a life of crime to one of asceticism.

Others

[1] B. WARD (trans.), Sayings of the Desert Fathers, (Mowbrays, 1975), p.24.

[2] D. G. R. KELLER, Oasis of Wisdom: The World of the Desert Fathers and Mothers, (Liturgical Press, 2005), ix.143.

[3] KELLER, Oasis of Wisdom, v.62.

[4] WARD, Sayings of the Desert Fathers, p.231.

[5] St ATHANASIUS, Life of Antony, trans. Robert C. Gregg (Paulist Press, 1979), Section 20.

[6] Rule of Saint Benedict, (Liturgical Press, 2001), Chapter 1.

[7] WARD, Sayings of the Desert Fathers, p.64.

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READERS’ COMMENTS

5 Comments

Submit a Comment

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

What a beautiful and helpful article Andrew – in my case, the revelation about staying has come through the immobility and dependence of a hip replacement operation at the end of August. Best wishes to your mum for her recovery

Thank you so much for this very helpful article Andrew, it is exactly what I needed today after going through a small crisis lately . It has provided some helpful words to my own thoughts and feelings. I wish you and your mother good health.

Thank you for this lovely and thought provoking article, Andrew. With all best wishes to you and your mother.

A lovely essay, Andrew: thank you.

I recently read this in the Fusus in the chapter on Noah: “For the people of dazzlement there is rotation and circling around a central point from which they never depart.[whereas] The people of the path … incline away from the real goal, looking elsewhere for what is already within them…. For them there is a ‘from’ and a ‘to’…. “

Really helpful…I have found the David Adam stuff helpful in lockdown , his love of the early British ‘saints’ Aidan, Cuthbert etc. I am from an evangelical/pentecostal background but am finding a rich vein of faith in these early Christians. They have much to teach us. Certainly challenged by your thoughts of wanting to ‘move on’ rather than living in the sacrament of the present momentr. From a fellow Pilgrim, Martin Beesley.