Well-being & Ecology _|_ Issue 9, 2018

The Unity Of Bee-ing

An interview with Heidi Herrmann about the work of The Natural Beekeeping Trust in preserving our precious populations of bees

The Unity of Bee-ing

An interview with Heidi Herrmann about the work of The Natural Beekeeping Trust in preserving our precious populations of bees

The biologist E.O. Wilson has called bees “the heart of the biosphere” because of their central role in the wellbeing of the planet. They are responsible for 80% of all plant pollination, including about 75% of the food we eat, but the last few decades have seen a radical decline in their numbers. Scientists blame a deadly mix of pesticide use, loss of habitat, disease and climate change. But until recently, less attention has been given to the destructive effects of modern beekeeping practices. The Natural Beekeeping Trust [/] is a pioneering organisation promoting alternative, bee-friendly methods. Jane Clark and David Hornsby talk to its founder, Heidi Herrmann, and ask her about the broader lessons we can learn from these extraordinary creatures who have been regarded, since ancient times, as sacred messengers.

At a time when populations around the world are under threat, it is a pleasure to have some good news about the state of bees. And this is certainly what we receive in Heidi Herrmann’s beautiful garden on the Sussex Downs in the south of England. On a warm day in May, it hums with the sound of bees visiting foxgloves and daisies, buzzing peacefully in and out of the miscellany of brightly coloured hives which line the perimeter of her land. We talk at her kitchen table, where French windows open out onto a patio containing five or maybe six active hives; when she goes outside, the bees surround her, forming a black halo around her head, but she shows no fear. The sense of tranquillity is infectious; we follow suit, without any sense of wariness.

At a time when populations around the world are under threat, it is a pleasure to have some good news about the state of bees. And this is certainly what we receive in Heidi Herrmann’s beautiful garden on the Sussex Downs in the south of England. On a warm day in May, it hums with the sound of bees visiting foxgloves and daisies, buzzing peacefully in and out of the miscellany of brightly coloured hives which line the perimeter of her land. We talk at her kitchen table, where French windows open out onto a patio containing five or maybe six active hives; when she goes outside, the bees surround her, forming a black halo around her head, but she shows no fear. The sense of tranquillity is infectious; we follow suit, without any sense of wariness.

The hives are thriving, she explains: she lost hardly any during the last winter, and now she is on the lookout for swarms, which happen between May and July. Usually when they come, she gathers them up by hand and coaxes the colonies into empty hives, increasing her population year by year. But this year she has been preoccupied, tending to one of her sheep who is dying, and she has not been able to give the bees their usual attention. But they have helped her out; the swarms that have already happened rehoused themselves without any intervention and are now establishing themselves in healthy new colonies.

De-stressing the Bees

All this is the end of a long journey for Heidi, which began nearly 20 years ago. “I started out as an ordinary beekeeper,” she explains; “I bought the kit, I set up a hive, I went along to beekeeper meetings, etc. Looking back, I can now see that there were all kinds of signs that things were not quite right. I remember watching whilst a whole bunch of people in white suits gathered round a beehive in order to smoke the bees. The hive rose up in a kind of kind of cloud and circled around, and they made a particular kind of buzzing noise which I now understand shows that they were in a state of high alarm. But when you are new to it, all this is presented as normal, and so I did not really think twice about it.”

The first turning point came at the end of her second year, when she was visited by a bee inspector from DEFRA. After the inspection, he asked her whether she was treating her hives against the varroa mite, which has been a major factor in the decline of bee colonies worldwide, and she confessed that she was not. “He gave me a packet of strips to hang inside the hive. It was about a week before I opened it: the first thing I noticed was that there was a terrible chemical smell, and the second thing was the logo, which was Bayer, a German company. I had been doing some reading and I knew that Bayer was a company who produces pesticides (although these days they don’t call them pesticides, they use the term ‘crop protection’), and that people in France and Germany were suing them for the death of millions of bees. So I felt instantly that there was something not right and did not use them.”

Heidi’s garden in May. Photograph: Jane Clark

At the end of the second year, the bees were riddled with varroa, but Heidi was encouraged by the fact that she had not actually lost any colonies and persisted in refusing chemical intervention. “I knew that all that would happen was that the bees would develop resistance, and then there would have to be new treatments, and so in the long run it was a vicious circle.” Then in the third year, she began to explore the possibility of alternative approaches. “I felt very alone because I had nobody to discuss this with. I had started beekeeping with a friend who was a priest, and he had a very reverent attitude, encouraging me to consult the bees and talk to them. But he was losing his own colonies to varroa and did not know how to advise me. He said, ‘You just need to sit with the bees.’ This was good advice and so that is what I did.”

The idea came to her that a lot of the practices she had been taught were stressing the bees, and that if they were having to cope with the varroa mite, then they needed energy and good immune systems. “So I engaged in a careful analysis and kept a diary of my observations. I also immersed myself imaginatively in the colony and tried to imagine what it was like when, for instance, the roof was taken off the hive, or the honey was removed. Both of these are things which now I keep to a minimum.”

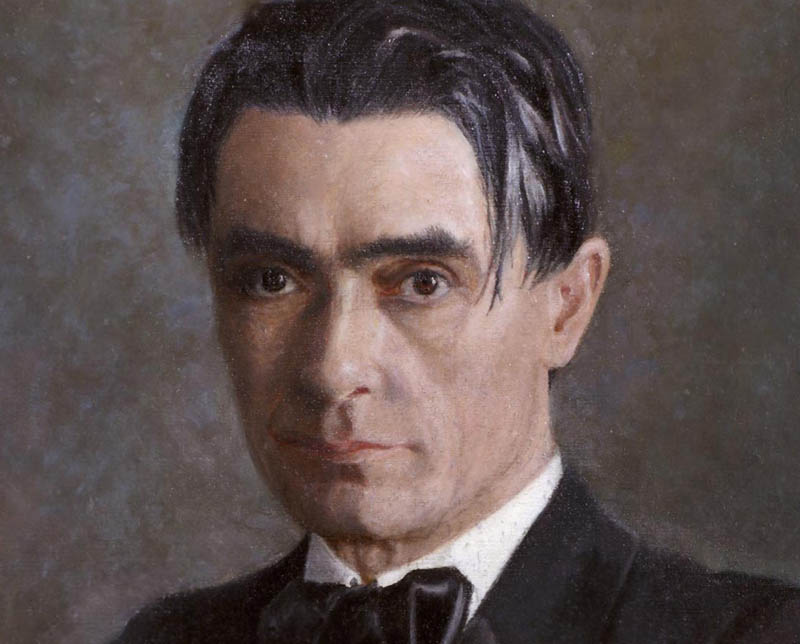

One of the major obstacles which Heidi had to overcome was the fear of being stung. A great influence upon her at this time were the bee lectures by the philosopher and anthroposophist Rudolf Steiner [/] – a series of nine extraordinary presentations [/], which he gave in Germany in 1923 covering all aspects of bee activity, from the nature of the collective ‘mind’ of the hive to the benefits of honey. “Steiner said that if you are afraid of the bees, then the bees will be afraid of you. So I started analysing the fear that one experiences when one opens up a colony. I realised that I would have to learn to control that a little bit, because I was aware that in ancient cultures the bees were regarded as holding secrets – sacred secrets – but nowadays we act in this very different way, approaching them with armour on.”

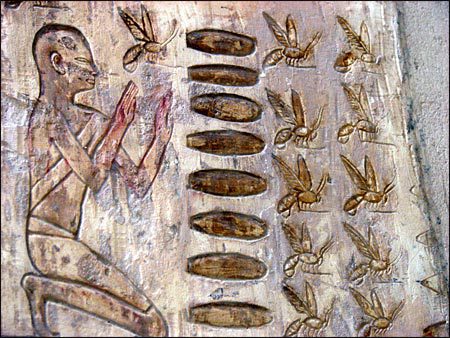

Beekeeping in Ancient Egypt. 26th Dynasty hieroglyph, showing the cylindrical pipe hives which are still used in Egypt today. There are more than 500 references to bees, wax and honey in known Egyptian writings

Approaching someone wearing ‘armour’, she realised, is a message in itself. “It would have an effect if you approached another human being like that. So I started to leave off parts of the protective gear: I took off my gloves, I went barefoot, or I left off the veil. There is an ancient Egyptian representation where someone is kneeling in front of the bees, and I filled my mind with that image. I was very pleased when I first managed to open a hive without protection, going very slowly and carefully; it was a moment of a kind of unity.”

She also revised her attitude to the venom transmitted when bees sting, learning that even that has healing properties which can be used as a therapy, termed ‘apitherapy’ [/], for conditions like arthritis and multiple sclerosis. “As soon as you start to regard the venom as useful, and think about the sacrifice that the bee makes in order to give it to you, things change. I was still stung sometimes, but my attitude towards it was different.”

Gradually, she began to feel that some kind of trust developed with the bees. “Later on I made a kind of covenant with them, when I promised to devote myself to them for the rest of my life. This happened after a very difficult situation when I accidentally found myself surrounded by a crowd of angry bees when I was not wearing any protection. I was clearing out a shed for someone and we did not know that there was a colony there. They were buzzing alarmingly around my head in their thousands. They were furious, and the situation became extremely tense and scary. I started talking to them inwardly, explaining that I did not mean to harm them. It was a huge effort to summon myself. Then gradually I felt them leaving my face, and the sound they were making changed. I opened my eyes cautiously and saw that they were swirling around me peacefully. It was a miracle that I was not stung by even one single bee. I felt that this whole incident was a kind of inspiration which encouraged me to carry on down this path.”

Heidi with a swarm of bees. Photograph: NBKT

The Natural Beekeeping Trust

The founding of The Natural Beekeeping Trust came a bit later in 2009. Heidi and a group of local people involved in alternative forms of farming used to meet for a weekly study and discussion group, and one day they found themselves talking about ‘The Marie Celeste Syndrome’ [/]. This was the name given by the popular press to a phenomenon where one third of beehives in the USA had failed to survive the previous winter, suffering from what is officially known as ‘Colony Collapse Disorder’. (The ‘Marie Celeste’ was a ship found abandoned at sea in 1872 with no sailors on board, and the name was used because of the absence of dead bees in many of the failed hives.) Heidi explains that this was a key moment for her own development: “In the popular papers and on TV, the phenomenon was always referred to as ‘mysterious’, whilst at the same time there was lots of footage of the monocultures they have developed in America, and the trucks transporting wheat or maize or whatever. All the elements which explained what had happened were on display, but it was still referred to as ‘mysterious’. I was personally outraged by that: it seemed like a denial of something that was staring us in the face.”

So what was it that was ‘staring us in the face’? “I was already aware of the effect that modern-day pesticides have on bees in Europe, but I had not realised until then just how bad American agriculture had become. In these monocultures they have reached a stage – given the nature and the amount of the pesticides that they use, and the cocktails of pesticides they have created – where agriculture is really a kind of warfare against nature. At the same time, it is still a form of agriculture, and so it cannot happen without bees. But they have destroyed the whole basis of the ecosystem to such an extent that no bee colony can survive there.”

‘Guardian of the Oak’ was the winner of the NBKT International Photographic Competition 2017 [/]. It shows a wild bees nest in the hollow of an old oak tree in South Africa. One can see the guard bee raising her front legs as bees arrive back at the hive, and the rapid negotiations following each arrival. Photograph: Jenny Cullinan of UJUBEE [/]

The discussion prompted by these events led directly to the setting up of the Natural Beekeeping Trust (NBKT). Registered as a charity, it now hosts an informative website giving advice on bee-friendly practices and gathering together the latest scientific research. It also organises courses and workshops, publishes books, and generally promotes a bee-centred approach through talks and media appearances. It has rapidly become a focus for an international network of individuals and organisations who are working together to find new ways – or revive old ways – of beekeeping that increase ecological resilience. At the end of August, for example, the NBKT will be co-organisers of a major conference in the Netherlands – the first of its kind – entitled ‘Learning from the Bees’ [/], which will bring together leading scientists such as Peter Neumann [/] (Institute of Bee Health at the University of Bern) and Thomas Seeley [/] (Department of Neurobiology and Behavior, Cornell University) with beekeepers and conservationists from all over the world, with the aim of forming an integrated strategy.

One of the most encouraging aspects of the Trust’s work is that it takes a wide perspective on the task of guarding and protecting the bees, acknowledging what it calls ‘their all-encompassing purpose’. Its patron is the UK Poet Laureate Carol Ann Duffy, whose understanding extends beyond merely ecological considerations to the spiritual and symbolic role of bees in human life. Bees are the ‘world’s mantra’ she writes in ‘Hive’ in her 2011 collection The Bees.

For this

let gardens grow, where beelines end,

sighing in roses, saffron blooms, buddleia;

where bees pray on their knees, sing, praise,

in pear trees, plum trees; bees

are the batteries of orchards, gardens, guard them.

Similarly, representatives from the arts will be at the Netherlands conference. This wider aspect very much concerns us at Beshara Magazine, but before moving on to the spiritual side of things, we ask Heidi about some of the specific practices advocated by natural beekeepers and how they differ from conventional methods.

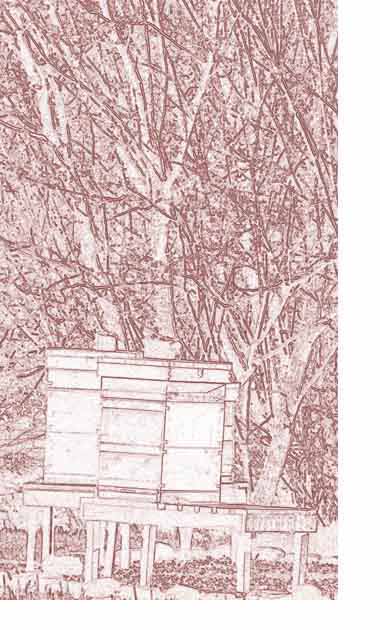

An oak log hive, hand-made at a workshop. See http://beekindhives.uk/2015/07/09/making-a-log-hive/ Photograph: Matthew Somerville

Natural Beekeeping

The most important difference, she explains, is that the NBKT promotes ways of working in which the needs of the bee are put above our own need to harvest honey or wax. This approach is firmly based on understanding the biology of the honeybee, and it is fundamental that the bees need to swarm. A bee colony is not merely a collection of individuals but should be seen as an organism in its own right. The German word ‘Bien’ (rhyming with ‘queen’) – which can be translated as the ‘Bee’ – has been coined to denote this unified entity. “Swarming is the way that the bee reproduces”, maintains Heidi. “Every year or alternate year, the mother colony divides, creating at least one daughter colony, sometimes more. But this is seen as undesirable if your main aim is to harvest honey. The first swarm is usually of the resident colony, with an experienced queen who has already mated so that she is set up for the next year. Part of the colony will go with her, and those bees know that they are going into uncertainty, as it could take days to set up a new home. So they prepare by filling their honey stomachs to bursting point. There is a kind of lethargy in a colony about to swarm which one can often sense if you are watching out for it.”

Because of this loss of honey – and, of course, the danger of losing the swarm altogether – many beekeepers try to prevent swarming by clipping the wings of the queen bee so that she cannot fly, or culling the drones. There are also controlled breeding programmes aiming to produce the ‘best’ queen, which are then imported into hives in order to increase productivity and ease of handling. But for Heidi, swarming is one of the high points of the beekeeping year, a time when one can see and experience the wholeness of the bien most directly. Recent scientific research (see for instance a seminal paper by Peter Neumann [/]) also supports the principle of allowing natural selection to operate freely. “Colonies that swarm are rejuvenated,” Heidi explains. “They also demonstrably cope far better with the varroa mite, for complex reasons that are not fully understood but which include the fact that swarming interrupts the varroa mites’ breeding cycles. There are also many other indications that the ‘best’ queens result from the swarming impulse. In fact, natural selection is something the bees are really good at. Most of my colonies survive, and I don’t import queens or bees from other hives. So over time I have gathered more and more good bees.”

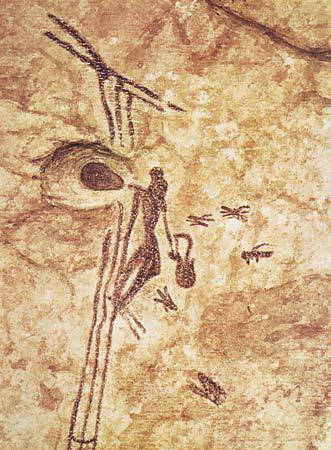

The earliest known painting of bees, Mesolithic cave painting 8-6000 bce.

The major challenge for bee colonies after completing the swarming cycle is surviving the winter and to do this they need both warmth and food. To ensure supplies, they build up a store of honey in the combs, but it is common practice now to regard this as surplus and to remove frames at the end of each summer. Indeed, many beekeepers remove all the honey not just at the end of the summer but on each occasion that the bees store any significant amount. “This practice is supported by the misguided notion that honey taken from a hive can be replaced with sugar water, as if the two are equivalent. But they are not. Honey is an extraordinary thing: it contains nearly 200 different substances, many of which are essential for the health of the colony, whereas simple sugar water contains two substances – sugar and water. Microscopy shows that bees fed sugar water have intestines that are shrivelled and dull, in comparison with bees fed honey whose intestines are plump and shiny.”

Natural beekeeping, by contrast, is careful to only remove honey which is genuinely surplus, and the NBKT website advocates keeping even some of that back in case the beekeeper has underestimated the quantity that the bees will need over a particularly tough winter or fallow summer. For Heidi now, honey is only of importance for the bees: “Our aim is to preserve the bees as pollinators, which is hard enough given what we are doing to the world of flowers. The bees are so short-changed in what we give to them these days: they are losing their habitats, they are losing the variety of flowers, and those they do find are often poisoned by pesticides. These are things over which we have no control. All we can do is allow them to build up their strength so that they cope.”

Sun hives in Heidi’s porch. Photograph: NBKT

Alternative Hives

Another major area of work for the Trust is to promote alternative hives which support the bees’ need for heat and privacy. If the colony as a whole is regarded as a single ‘super organism’ then the hive can be seen as the outer shell, or skin, of that creature, and within it a certain atmosphere consisting of warmth, scent and moisture is generated when bees nest naturally. Research has shown that this is also germ-free because of the particular properties of the substances produced within the brood-nest. However, the box-shaped hive, named after its inventor Lorenzo Langstroth, which since the mid-20th century has been adopted as more or less standard worldwide by conventional keepers, does not allow this kind of environment to develop. NBKT therefore sees the Langstroth hive, whose main aim was to make it easy to extract honey, as one of the many problems which need to be addressed, and they actively promote alternatives.

One of these is the sun hive [/], which was invented by beekeeper and sculptor Günther Mancke. Based on meticulous observation of the bien, this mimics many of the characteristics of wild hives. It is cocoon-shaped rather than square, for, as Heidi explains: “The idea is to offer the bees a home which is the archetypal shape that they would choose to construct their brood-nest in, say, the hollow of a tree. It also allows the bees to enter from a bottom entrance as they would in the wild.” The hives are woven out of rye grass and one of their most charming features is that they are not made commercially; they have to be constructed individually by hand, and one of the trustees, Rachel Hanney, has taught many beekeepers how to make them at special NBKT workshops.

Inside the sun hive, showing how the combs reflect the natural shape of the hive. Sun hives are not designed to produce honey, but if it is desired, then an additional box can be added at the top where bees can deposit excess. Photograph: Gaia Bees video screen capture

There is also increasing interest in tree hives [/], a growing movement which has become the special interest of another NBKT trustee, Jonathan Powell. This is a 1,000-year-old tradition of keeping bees in a living tree, with the guardianship of the hive passing on from one generation to another. This has been preserved in Poland and in the Southern Urals of Russia by the Baskhir tribe, and is now being revived and established across Europe. The first UK experiment [/], in collaboration with the Trust, is taking place at Pertwood Organic Farm in Wiltshire. Alongside this is a revived tradition of building log hives which can be mounted up on trees or raised on legs; this has been the particular province of an NBKT associate, Matthew Somerville [/].

An important characteristic of all these hives is that they are mounted high up. This is because research has shown that when bees are free to select their own site, they always choose to live between 2.5m and 6m off the ground. “The bee is not an animal that wishes to live on the earth,” says Heidi. “It only does so because we want it to and to make it easier for us to take the honey out. In itself, the bien is naturally elevated.”

Working on a tree hive. This ancient practice, which has been maintained for centuries in Eastern Europe, recognises the bees’ natural inclination to live high above the ground. Photograph: courtesy of Jonathan Powell

The Elevation of the Bee

This brings us to a discussion about the symbolic meaning of bees and their ‘all-encompassing purpose’. Since ancient times, they have been regarded as sacred creatures, messengers of the spirit world. The Ancient Egyptians [/] saw them as the tears of the Sun God Ra and made them into the emblem of their royal power, whilst for the Greeks, noting that the hive is almost entirely female, they were the embodiment of the Great Mother Goddess. They have been seen as symbols of wisdom because, collecting pollen from many flowers, they transform it into golden honey; and of hard work and intelligence because of the extraordinary complexity of their activities and community. The Christian Father St John Chrysostom maintained that “the bee is more honoured than other creatures, not because she labours but because she labours for others”, whilst the Qurʿān singles them out by naming a whole chapter after them, and giving them prophetic status:

And your Lord gave inspiration to the bees. “Take for yourselves houses in the mountains and the trees and in what men build. Then eat of all the fruits and follow the ways of your Lord, which will be easy.” (Q.16:68–9, Surāt al-Naḥl)

In our conversation with Heidi, it is this elevated nature of bees that emerges as the most important characteristic. She herself refers back to Rudolf Steiner, whose bee lectures have received renewed attention in recent years because he foresaw in 1923 that new beekeeping practices, particularly the artificial breeding of queens, would lead to the extinction of the bee within 80 to 100 years. “Steiner maintained that the insects that live in colonies – the ants, bees and corals – are the most-highly developed beings in the animal kingdom. They are very highly evolved, and they organise themselves in ways that are deeply mysterious and beyond our normal physical understanding. They are messengers of a higher world – earthly representatives of something very elevated.”

Portrait of Rudolf Steiner. Photograph: Rudolf Steiner Archive [/]

Steiner also thought that bees have a special position in giving us, as human beings, information about ourselves. In his second lecture he says:

Beekeeping has at all times been highly valued; in olden times especially, the bee was held to be a sacred animal. Why? It was so considered because… quite wonderful riddles lie concealed in all that happens with the bees, and by much studying of them one can learn to know what happens between the head and the body in man.

Steiner’s own examples included the transformational processes by which wax and honey are produced within the hive, which he saw as reflecting processes which take place within us. In the contemporary world, ‘much studying’ by scientists has yielded further fascinating insights. A leading figure is Professor Thomas Seeley of the University of Cornell, a great supporter of the natural beekeeping practices who will be speaking at the Learning from the Bees conference in August. His book, Honeybee Democracy, is a detailed investigation of the decision-making process by which a swarm chooses a new home, revealing that there is no ‘top-down’ command from the level of the queen. Rather, the whole hive, which can consist of between 2,000 and 30,000 individuals, comes to a consensus decision based upon the quality of the dances of the scouts who are sent out to explore possible sites. In this Seeley sees not only a model by which we, too, might come to better consensus decisions at a social level, but also a reflection of the way that the human brain works; here also, it seems, there is no ‘top-down’ command structure, but a process by which millions of neurons come to some sort of consensus decision about ‘best action’ (for more on this, see his talk [/]).

The ‘waggle-dance’ of the bees, giving information about the location of good pollen or, during swarming, a suitable new home. Painting by Arif Turan [/]

But what does Heidi think about our present state of affairs? What ‘message’ are we to take from the present plight of the bees in the world? “The plight of the bee is mirror to the plight of our own humanity. When I saw what was happening in the USA, my thought was they have degraded the bee to a level where no further degradation is possible. And what this means, really, is that human beings have degraded themselves to a level that was previously unimaginable. So we need to address the many ways in which we have fallen so far from the ideal place of humanity. This is very clear. The bees demonstrate this as a whole phenomenon – as ‘the Bee’.”

So what is it that we have fallen away from? “From a sense of wholeness, of things being ‘one’. I think we have lost this so completely that all that we have now is an occasional inkling. Nothing in the way we live or shop or ‘consume’ suggests that we have the slightest notion of our interdependence of everything living, including ourselves. We are interdependent with a world that we are destroying, and we are distracting ourselves from the massiveness of the problem by allowing ourselves to become addicted to technologies and entertainments and so forth. I can see the temptation of all this – I myself am the owner of an iPad, and I am also on social media: in fact, it is hard to be part of any campaigning group, as the NBKT is, without using social media and the internet these days. So I am only too aware of what it is like to be sucked into the world that only these technologies create.”

The Bee as a Symbol of Love

Finally, we ask Heidi what she herself thinks she has gained from her work with the bees. She tells us: “They have provided me with very extraordinary experiences, and I feel that they act as consolers: they make me feel more at home in the world. They have also made me question all conventional wisdom. I have had close contact with sheep and with horses, but I feel that the bees are representatives of ‘unknowing’ in the animal realm, unlike anything else.”

There is also an aspect of demanding a certain kind of state when working with them: “I am not a good meditator by nature, but I think that a certain meditative attitude is essential when interacting with any living thing. In a non-meditative state, we are often not really living in the present; we are worrying about things that happened in the past or things that might happen in the future, and there is a restlessness and a kind of fear.

“I also feel that our powers of intuition are strengthened by hanging out with the bees. This is not because of our merit or our training, although these might have an effect, of course – but in the presence of the bees, we do not have to try very hard to be taken into a prayerful mood. What kind of animal is it that can produce this effect? I don’t feel the same with a single bee or a bumble-bee: it is something that happens in the presence of the Bee as a community.”

Bees taking pollen from apple blossom. Photograph: Zoonar/Galina Tolochko/Alamy Stock Photo

And what of an aspect that until now we have not touched upon at all – Rudolf Steiner’s assertion in the very first of his bee lectures, that bees are above all a representative of love. In fact, he maintained that:

One only begins to understand the life of the bees when one knows that the bee lives in an atmosphere completely pervaded by love… The bees suck out their food — which they then turn into honey — exclusively from those parts of the plants that are centred in love; they bring, so to speak, the love-life of the flowers into the hive.

Heidi agrees completely: “Love for me is to do with being utterly selfless. I also believe that there is the power of our love for a living creature. I don’t think we need to be apologetic about thinking like this. After all, so many people have pets that they love and who thrive on it. I once gave a talk to a group of very conventional beekeepers in Wimbledon. I talked mainly about the loss of habitat and the reduction in biodiversity of flowers, because I thought that we would all agree about these problems. I explained at the end that I leave my bees alone, believing that they are capable of organising their own lives.

“Then I was challenged quite aggressively in the question and answer session about the fact that I don’t treat my bees against varroa. I found myself saying – in fact, I felt that I was inspired to say: ‘Well, when I say that I don’t treat them, I meant that I don’t use chemicals or oxalic acid. But I do treat them – not in the way that you might mean, but with love.’ And this got applause from the audience, because actually, we all understand that, whether we are working with bees in a conventional way or a natural way, this is the basis of our relationship with them. Or maybe we can say that the altruistic urge, the aspiration to love, is what really distinguishes us as human beings.”

Hive

Hive

by Carol Ann Duffy

All day we leave and arrive at the hive

concelebrants. The hive is love,

what we serve, preserve, avowed in Latin murmurs

as we come and go, skydive, freighted

with light, to where we thrive, in time’s hum,

on history’s breath.

industrious, identical…

There suck we,

alchemical, nectar-slurred, pollen-furred,

the world’s mantra us, our blurry sound

along the thousand scented miles to the hive,

haven, where we unpack our foragers;

or heaven-stare, drone-eyed, for the queen’s star;

or nurse or build in milky, waxy caves,

the hive, alive, us – how we behave.

Image Sources (click to open)

Banner: Heidi Herrmann amongst her beehives. Photograph: The Natural Beekeeping Trust.

First inset image: Two honey bees on a French lavender flower. Photograph: Michael Willis/ Alamy stock photo.

Image inset with ‘Hive’ poem: Photograph by Simon Blackwood.

Other Sources (click to open)

Image inset with ‘Hive’ poem: Photograph by Simon Blackwood

Natural Beekeeping Trust Publications

Jonathan Powell, The Tree Beekeeping Field Guide (ebook)

Günther Mancke, The Sun Hive (German original, 2005)

Iwer Thor Lorenzen, The Spiritual Foundations of Beekeeping (2016)

Iwer Thor Lorenzen, Bees and the Ancient Mysteries (2018)

See also Heather Swan, Where Honeybees Thrive (Penn State University Press, 2017) for a good overview of natural beekeeping strategies.

See also Heather Swan, Where Honeybees Thrive (Penn State University Press, 2017) for a good overview of natural beekeeping strategies.

For information about the forthcoming conference ‘Learning from the Bees’, see https://www.learningfromthebees.org

Rudolf Steiner, Nine Lectures on Bees, Given to Workmen at the Goetheanum, Dornach, Switzerland, 1923. Translated by Marna Pease and Carl Alexander Mier. https://wn.rsarchive.org/Lectures/GA351/English/SGP1975/NinBee_index.html

Paul Neumann & Tjeerd Blacquière, ‘The Darwin Cure for apiculture? Natural selection and managing bee health’ in Evolutionary Applications, Vol. 10, Issue 3, March 2017, pp.226–30. See https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/eva.12448

Thomas D. Seeley

The Wisdom of the Hive: Social Physiology of Honey Bee Colonies (Harvard University Press, 1996)

Honeybee Democracy (Princeton University Press, 2010)

Following the Wild Bees (Princeton University Press 2016)

Carol Ann Duffy, The Bees (Picador, 2011); quotes from ‘Hive’, p.31 and ‘Virgil’s Bees’, p.23.

Email this page to a friend

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

A Biology of Wonder

An interview with scientist Andreas Weber, whose radical ideas are transforming our understanding of nature

Poacher’s Pilgrimage

A journey with Alastair McIntosh – poet, theologian, environmental activist, prophet of a new Scotland and a new world, and interfaith traveller

Thought for Food

Charlotte Maberly on the new science of Gastronomy

A Thing of Beauty…

The Chauvet Caves in the Ardèche, Southern France

READERS’ COMMENTS

Wonderful…!!!!

Thanks for the information, insights ….and the inspiration!! Stay blessed!

What a wonderful article, and what a wonderful person Heidi Herrmann is. Her bees are fortunate to have her as their guardian.

Fascinating article of Bee-ing offering inspiring insights into new ways of living and interacting with some of our world’s most precious creatures.

Thank you for interviewing Heidi Hermann. The world needs her wisdom!

Finally time to read this inspiring article. I only wish I could’ve made the conference.

I like the theme of this blog. Where can I download it?

카지노사이트

Thank you for sharing, this article has taught me a lot of new knowledge. If you are facing the problem of how to choose a jersey, welcome to visit my website: Cheap Sports Jerseys