The Unity of Humanity

An Interview with Professor Todd Lawson

THE UNITY OF HUMANITY

An interview with Professor Todd Lawson

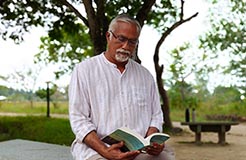

Todd Lawson is Emeritus Professor of Islamic Thought at the University of Toronto, Canada. He has published widely on Quran commentary, the Quran as literature, Sufism, and the Babi and Baha’i traditions. His book, The Crucifixion and the Quran was published in 2009, followed by Gnostic Apocalypse and Islam in 2011; he is also the editor of Reason and Inspiration in Islam, a collection of essays bringing together the disciplines of theology, philosophy and mysticism.

He is currently writing a book on the Quran as sacred epic. Todd embraced the Baha’i faith when he emigrated from the USA to Canada in his late teens, and remains an active participant of that community. He lives in Montreal, and we caught up with him during a recent visit to Oxford, where he gave a talk at the symposium of the Muhyiddin Ibn ‘Arabī Society entitled ‘Water, Light and Knowledge: towards an ecology of the imagination’.

Interview by David Hornsby and Jane Clark

We understand that you were born and raised in Indiana, then moved to Canada to escape the Vietnam era draft. Subsequently you taught for 25 years at the University of Toronto in the Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations.

We understand that you were born and raised in Indiana, then moved to Canada to escape the Vietnam era draft. Subsequently you taught for 25 years at the University of Toronto in the Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations.

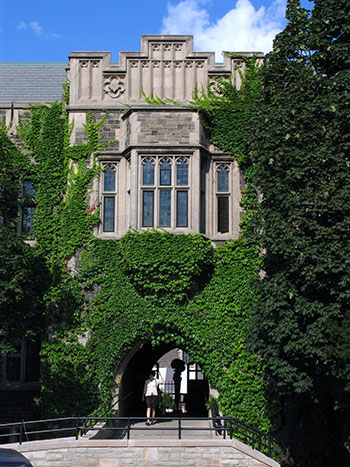

Yes, that’s right. The University of Toronto is the place that I taught the longest. I have taught other places – in McGill University in Montreal for a while, and I also taught here in the UK at the Institute of Ismaili Studies in London.

How would you describe in a nutshell the deepening considerations of our humanity which many years of teaching this subject has brought you?

One of the main things I have learned is the enormous debt that society, humanity and civilisation at large – to the degree that it is civilised and humane and social – owes to Islam and the Islamic venture. This has been my ongoing interest. Growing up where I did, being born where I was, going to school in Indiana, we knew nothing of Islam or Muhammad or Muslims, and I think we never even heard those words mentioned the whole time I went to school or was at university. Even in history courses, in college or high school, these subjects never came up.

Christianity was of course the default ‘spiritual water’ and we celebrated Christmas, went to church periodically and so forth. But when I got to Canada in January of 1968, the first people I met were Baha’is. I had the name of one of the group from a friend in Indiana, and had been advised to get in touch. They were very kind to me and hospitable, helping me to situate myself in the country. Baha’is by teaching, doctrine and belief are apolitical, so they were not active anti-war people, but they were very sympathetic human beings and looked after me. In the process, they also introduced me to the Baha’i religion, and it was through reading some of the texts that I eventually came to realise that they were full of references to the Quran, and to the Prophet Muhammad and to Islamic spirituality. This really spoke to me somehow.

Was it the Baha’i pronouncement of the end of Jihad (holy war) that appealed to you?

Well, I didn’t know enough to know how important that was, at the time. I was completely innocent of anything to do with Islam. And actually, as you know, Baha’is do not call themselves Muslim and they do not call the Baha’i faith Islam. The Baha’i faith identifies itself as having acquired a new ethos, one that is distinct from Islam, even though there is much Islamic DNA in the Baha’i message – the Baha’i daʿwa (invitation) one could call it. What struck me at the beginning was that within the Baha’i articulation of its own specific vision was the interesting idea that there had been a new manifestation of God, a new prophet ‘sent to earth’. I thought at first: this of course is absurd, this is an old mythic way of thinking about the way life goes on. We don’t deal with prophets anymore in the modern age. But then as I read more and I thought about it and looked at it, I said to myself: Well, why not keep an open mind? Ultimately, I don’t know enough to say that it’s impossible.

Because it was a relatively recent prophecy, was this process of evolving revelation something you felt you could participate in?

In a sense, what got me was that it was too easy to say no. It was too easy to just say: these people have their heads in the clouds. So I decided that I was not going to do that. I was going to think about it and look into it. Certainly everything Baha’u’llah spoke about and said is something that humanity can use: the abolition of war, as in the abolition of jihad; the abolition of prejudices of all kinds – racial, sexual, economic; and the breaking down of barriers between people. This all sounded good to me and felt like a healthy thing for the world to be engaged with.

This was in the context of huge turmoil in the culture that you had come from?

There is no doubt that it was a refuge, both psychologically and socially, and also individually, because I had left my family. When I left Indiana I was just 19, and thought that I would never see my family again. The Baha’is I met were as lovely as people could possibly be and had the right idea about the world. I felt I had been guided and felt grateful. Then, as I became more involved in the Baha’i faith, I became more and more interested in the Islamic connection. Where does the Baha’i faith acquire its new identity? Where does the Islamic identity end? What are the differences and what are the similarities between the two faiths? I felt this was, for me, a very important area of research.

How did you set about making an intelligent enquiry into what was going on?

This interest took a while to form. In fact, it took five or six years to become articulated in the way I have just spoken about it, and it happened after I had become a Baha’i and been active in the community. It came to a head when I returned to university after being out of education for a while. In the meantime, I did all sorts of things; I was a taxi driver, a printer, I worked in a steel mill. I was even a lumberjack. I had a family, was married and had a daughter. But one day I decided that life could not go on like this, I had to do something else, and so I went back to university with the idea of becoming a lawyer.

Then in the process of finishing my degree at the University of British Columbia, I became interested in studying Islam. It just happened. I took a course in Islamic studies and there was a teacher called Hanna Kassis who is well known in Islamic studies for his concordance of the A.J. Arberry translation of the Quran. He was one of the first people to apply computer know-how to texts. Kassis was a literary man, and he was also deeply spiritual and especially sensitive to the faiths of others. His classes were very popular because he was an excellent teacher. He was a Palestinian Christian but he loved the Quran. He glowed at the mention of the Quran, and he glowed when speaking about it to the class. His enthusiasm was contagious.

From that point I dropped the idea of law, and enrolled at the Institute of Islamic Studies in Montreal. I did my Masters’ degree there and then my PhD. I was interested in the Quran from the beginning and so I did work in Quranic commentary in both degrees, and in the process began to formulate my ideas about the relationship between the Baha’i faith and Islam. Now and then, from time to time, I have taught courses in the Baha’i community on Islam and the Quran within the Baha’i faith. Baha’is all know there is an Islamic component to the religion, and there is great interest in it, especially these days, given the way in which Islam is portrayed, and the culture in general. Due to political events and biased news reporting, the general image of Islam these days is highly distorted, and Baha’is feel just as uncomfortable about this as Muslims themselves.

In the ’70s, the Islamic presentation to the West, at least in the UK and Europe, was all to do with the beauty and environmentally sound practicality of Islam. This became identified with a kind of utopian ideal. In the ensuing 40 years, the day to day perceptions of Islam have changed from the very positive and appealing image associated with, for example, events such as the World of Islam Festival in London, and seem to have reverted to an almost siege-like mentality.

It’s true that things have turned upside down. Although in Europe and England, for geographic reasons, you have had more connection with Islam. In Canada, we had nothing like the World of Islam Festival. When I first started taking courses, I would get a thrill at finding the odd article that mentioned Islam in a newspaper. I would cut one out about every three months. So we didn’t have the appreciative phase in North America that you had with the World of Islam Festival. Rather we had groups like the Black Muslims, who were largely misunderstood by the general populace and terrified all ‘good’ middle-class people whether black or white.

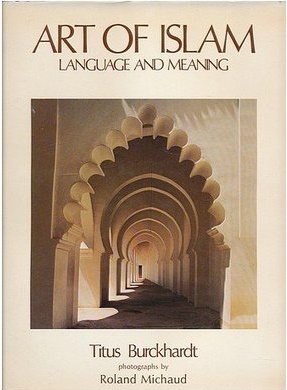

The World of Islam Festival took place in London in the spring of 1976. Its aim was to demonstrate the rich culture of Islam and its achievements in the arts, crafts and sciences. Backed by 32 Muslim nations, it included exhibitions, lectures and seminars at museums and universities in London and other cities, and produced a number of publications of lasting value, such as S.H. Nasr’s ‘Islamic Science’, Titus Burckhardt’s ‘Art of Islam, Language and Meaning’, and Martin Lings’s ‘The Quranic Art of Calligraphy and Illumination’

“Coltrane was rearranging the way we feel and experience sound and beauty, time and tonality; he takes us on some kind of journey and leaves us in a new place.”

Some people don’t like jazz because they feel that they cannot understand it. But understanding is not the issue. It’s a matter of feeling and trusting the person. For example, Coltrane – in whose music I seemed to hear from the very beginning a new and astounding intelligence – was rearranging the way we feel and experience sound and beauty, time and tonality, and all of these things; he takes us on some kind of journey and leaves us in a new place. This is precisely how I felt when I read The Seven Valleys of Baha’u’llah. There was a great deal that I didn’t understand, but it was beautiful. The English translation of the Persian was quite beautiful, and the things that came out of Rumi and the Quran, and Baha’u’llah’s own statements, the flow of the composition, was so new. It was very much like listening to ‘A Love Supreme’. I would read it over and over again.

The feeling that you got from this was that there was real meaning there?

Indeed. The deepest possible meaning, and, as you said, this was at a very difficult time in my life.

Would you say, given all this, that in approaching the Quran through the mirror of Baha’u’llah, you found a depth that people would often miss otherwise?

It is important to emphasise the Baha’i component, because this constitutes a hermeneutical stance. I have been predisposed to look at Islam the way I do because I am a Baha’i. And this point of view leads to the understanding that all prophets and all messengers from God are sent to bring forth an ever-widening and deepening complex “iteration” of the unity of humanity. This process began with the beginning of humanity, with the hunter–gatherers, through the village dwellers and agriculture, through the evolution of small towns, city-states and, eventually, nations. The Baha’i view is that the world is now in the process of finding this ultimately harmonious unity on a global and universal level.

Muhammad brought together a remarkable array of humanity under the same general spiritual law. It’s just astonishing. For me, it was reading and studying Islam that reinforced the possibility of the Baha’i teaching being correct and accurate, and on the right path as it were, because of the accomplishment of Islam.

But yet today the exact opposite appears to be happening and we are all finding it difficult to face the task of accepting one another. So, what’s going on?

It’s a terribly difficult question, and I don’t think I have an answer. But I can tell you what it is about the Quran that I think should be better known. Of course, we can think about the Quran in many different ways. If we had ten Quranically well-educated people in here and asked them to identify the five major themes in the Quran, they would all come up with different ones, all valid. In my recent thinking, I have become deeply interested by the degree to which the notion of humanity itself is a major theme in the Quran. It is not about the Arabs, the Persians, or the Middle Easterners: it is about humanity. This was the song that appealed to the great vast expanse of humanity which came under its umbrella, so that in such a short period of time Islam bestowed a universal set of spiritual and moral values upon a widespread and highly cosmopolitan population. A ‘citizen of the Dar al-Islam’ going from Cádiz to the Hindu Kush could experience this and feel at home: there was a unity of language, but more than that, there was a unity of symbols and the values of the religion itself that were established in these various places.

This is a great achievement, and the reason it was able to do this from a scriptural point of view is because the Quran validates and esteems the prophets of every community. There are 25 prophets mentioned in the Quran but the tradition tells us there are 124,000 who have existed. In fact, there is no human community that has not had a divine revelation. In terms of religion, this is a bit different from saying we are bringing the truth to some poor benighted savage that lives on an island. The Quran recognises that everyone has had a revelation, has been touched by a divine message, and that what it represents is a recent version or enrichment of the message.

The understanding is that all the prophets share the same source, the same light. Ibn ‘Arabi is so eloquent on this with the great defining metaphor of his Ringstones of Wisdom (Fuṣūṣ al-ḥikam) in which the setting of the ring is the prophet, and the jewel is the divine light that fits the prophet at the time. This comes straight from the Quran, which teaches that prophecy is something all humanity experiences regardless of geography, language, race or tribal interests. The God of the Quran has spoken to all humans, loves all humans, guides all humans.

The Islamicate gift to humanity is the understanding that we are all related. The myth in the Quran of the Day of the Covenant reinforces this (see Quran 7:172). The gist is that, according to these verses, at a sacred moment prior to creation, in a timeless time and a placeless place, all humanity that would ever be were gathered together in the presence of God who presented the famous question: “Am I not your Lord?”, and to which this same humanity all immediately responded “Yes, indeed!”. This sacred myth assures us that anyone who has ever lived or will ever live in the foreseeable or imaginable future was present there – and was there in peace, united in their own connection with each other through their connection to God.

How has your understanding of the Quran and its place in educating humanity evolved? Because it seems like there is a new understanding of the Quran that’s developing, and the translations that were done years ago were done with a different mind-set to the mind-set now.

This is a bit like the axiom that history should be rewritten in every generation. The Quran should be translated in every generation. There are clear problems in conveying the beauty of the Quran in translation because the Arabic symphony of the Quranic music is sui generis, and we don’t get that when we hear or read the English. Nonetheless, it is possible to communicate and talk about the Quran, and to teach people how it is connected with these great achievements that Islam brought to the world: serious scientific, social, organisational, and even military achievements – all kinds of cultural and civilisational advances that the West continues to benefit from. One of the problems with the West in my view is that it does not wish to confront or acknowledge the Islamic component that is deep within it – its debt to Islam, as it were.

“Many scholars now say that the idea of the university was an Islamically-inspired cultural achievement.”

Was your initial interest in the Quran literary or spiritual?

Our teacher revealed the beauty of the Quranic theophany to us because he could speak about how beautiful it was from a literary point of view. But the literary always carries a spiritual charge in that context, always. So I would say that I was interested in spiritual aspects from the beginning. What caused me to pay serious attention to the teachings of Baha’u’llah were the very spiritual writings that he composed, particularly those he wrote in the very early part of his ministry. For example, The Hidden Words is full of very beautiful spiritual maxims and aphorisms. However, the book that really inspired me was The Seven Valleys and the Four Valleys, which is about the journey of a soul through these valleys, and the spiritual heroism traced from the beginning to the end of these journeys. I know now that many of the paradoxes and insights of the greater Islamic mystical tradition were being deployed by Baha’u’llah in the composition and were Islamic in origin. At the time, I didn’t know this, although the editors and translators weren’t trying to hide it. Things were footnoted, so if they knew that something was from Rumi they would say so, or if it was the Quran, they identified it. This work by Baha’u’llah had a great effect on me. It was a bit as Keats describes in his poem ‘On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer’ – seeing a whole new world coming into view. I felt that it was very hopeful, to say the least.

What seems to be difficult for people when looking at works such as the Quran which can be read in many different ways, is how you ‘cross over’, as Ibn ‘Arabi puts it, from one level of meaning to another. Did you find that the Baha’i exposition moved your understanding forward in some way and made it more personal and essential?

I think maybe that might characterise what happened in retrospect. But at the time it felt rather different. I had already been exposed to improvisatory music, jazz particularly, before I left home. Perhaps the most important thing that happened to me in my education was listening to John Coltrane, and what I loved about this, what his art taught me, was that the apparent chaos of existence may have a thread of meaning running through it.

Can you give some concrete examples of the contributions that Islam has made?

Cultural historians argue that the European Renaissance would not have occurred – would have been impossible – without Islam. Many scholars now say that the idea of the university was an Islamically-inspired cultural achievement, and that the West took it up and developed it. This claim is controversial, but it is nonetheless important. Also, the way in which Islam actually periodises and talks about history has had a great influence on the way we see ourselves as human beings. And philosophically, we know, for example, that Thomas Aquinas had the books of Ibn Sina and Ibn Rushd and other great Muslim thinkers on his desk when he was writing his Summa Theologiæ. There was a great cross-fertilisation in Andalusia before the Reconquista between Islamic scientists and people of knowledge, and the Jews and the Christians. But perhaps most importantly, the idea of religion itself was given great impetus by the Islamic movement – the idea of the Abrahamic family of religions and so on. Islam brought a way of understanding and seeing harmony amongst the different religions.

Do you think that we are we still living in a genuinely religious era, or have we moved beyond religion into considerations of humanity and are better off without these religious structures?

There is an inherent spiritual dimension to humanity. You may call it religious if you like, but there will never be a time, as long as humanity exists, when there will not be a need for spiritual growth and satisfaction and nourishment. So, if this is ‘religion’, it will never die. Today, we are in the midst of a very materialistic and violent world society. We sell arms to the Middle East and then we watch the ensuing bloodshed on television while clucking about how violent ‘they’ are without true insight into the crucial interconnectedness at play. We are all in the same bloody boat, and it’s getting a little bloodier as time goes on. The cure for this, all religions would say, is spiritual, not material.

This is not to say that the cure is ‘religious’ inasmuch as this word usually denotes dogma and, perhaps more importantly, clergy. Another thing that appealed to me about the Baha’i teachings was that there is no clergy. There are no individuals who administer sacraments or act as intermediaries or monitor your salvation and see how you are coming along. Everyone is their own guru, for better or worse. The Baha’i faith is, in that sense, anti-clerical. Sometimes this is also seen as anti-Islamic and construed as such by its enemies in Iran and elsewhere, but it’s really anti-clerical. To this extent it is also ‘anti-religious’. However, I do not wish to mislead: there are principles and laws that require commitment.

So what would you say is the cure to the problems we now face in society?

It is as apparently banal and straightforward and un-sensational as putting into practice what are called in Islam the divine names and attributes, such as mercy, compassion, kindness, patience, chastity, being fair in your judgement. The Baha’i faith also believes in all these, but in addition it focuses on the socially and existentially destructive phenomenon of prejudice. When one feels prejudice, this is considered to be a serious spiritual disease, or a spiritual catastrophe which has deleterious effects in the wider world. It is a religious duty of human beings to monitor and eradicate prejudice in themselves.

“The reason people are swamped and overwhelmed by the technological promiscuity of the world is because they do not feel and sense the reality of the spiritual realm.”

On the very first page of the Quran, it says that this is a book that is not for everybody: it is for people who believe in the Unseen. If you don’t believe in the spiritual world, don’t trouble yourself. Secondly, it says that the people who believe in the spiritual world and who pray and fast and treat their neighbours well and observe all the spiritual laws that the Quran enunciates: they will prosper. It’s about prosperity. The word for salvation, najāh, occurs in the Quran, certainly. As we all know, there are very frightening visions of Hell and very appealing visions of Paradise in the Quran – this is part of its literary character – but salvation is not actually as important in Islam as it is in other religions. Much more important is the idea of prosperity, of having a peaceful, harmonious society. In fact, we date the beginning of Islam not from the birth of the Prophet or from the first revelation – although we know more or less when these things happened – but from the establishment of a community. This vision of human community in the Quran is something we can still benefit from.

Do you not think that this idea of community has become even more problematic with the way technology has moved forward? Society and community are under threat in the West and people are becoming more and more isolated.

The reason people are swamped and overwhelmed by the technological promiscuity of the world is because they do not feel and sense the reality of the spiritual realm. You cannot get away from acknowledging the reality of the spiritual realm, of the invisible realm, of the place that is not accessible through the senses. Even if it sounds like nonsense to the technocrat or the scientist, it is non-negotiable.

In the end, it’s up to us; the teachings of Muhammad, the teachings of Baha’u’llah, of all the spiritual teachers – they all say that we must return to the true thing within us, “He who knows himself knows his Lord”. They all quote this. We have to orient ourselves along a spiritual axis. What’s more, the Baha’i teachings are explicit about the fact that each person is responsible for their own spiritual growth. No one else. It’s a violation of the law of God to presume that anyone else has any business fooling around with one’s soul. And this is a beautiful thing. But with it of course comes responsibility.

And also humanity?

This is the great hope.

So do you feel that there is hope for the future? We seem to be at a pivotal point of deep uncertainty in many aspects of our lives?

There is a great uncertainty, and there are geniuses and spiritual seers like Muhammad, Ibn ‘Arabi, Baha’u’llah and many, many others, who provide clues for us. There is a kind of certainty that is toxic that we don’t want anything more to do with, which is the one that will allow you to harm other people for what you consider to be correct. But the Baha’i ethos, as I understand it, says rather the opposite. Whatever allows people to live together, that is the thing that is correct. That is how truth is defined.

Etymologically, to be prosperous means that your hopes have come true, that what you wish for has become a reality. We know from ourselves what each of us wants and what our hopes are. It’s pretty basic. Human beings want to live in peace, they want their kids to be happy, to marry someone beautiful and happy, to have peaceful lives and to be able to go about their business. This is a shared hope by everyone on the planet. It cannot be otherwise.

Please follow and like us:

Main image: Professor Todd Lawson at the 2016 Symposium of the Muhyiddin Ibn ʿArabī Society, Wolfson Hall, Oxford. Photograph courtesy of Ayman Saey and the Muhyiddin Ibn ʿArabī Society.

Books mentioned in this article:

Todd Lawson

The Crucifixion and the Quran: A Study in the History of Muslim Thought (Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2009).

Gnostic Apocalypse and Islam: Quran, exegesis, messianism, and the literary origins of the Babi Religion (London & New York: Routledge, 2011).

Reason and Inspiration in Islam: Theology, Philosophy and Mysticism in Muslim Thought (London & New York: I.B. Tauris in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, 2005).

‘Quran and Epic’, Journal of Quranic Studies (2014:16:1).

A full list of Todd’s publications can be found at www.toddlawson.ca.

You can also find podcasts and videos of Todd’s presentations to the Ibn ‘Arabi Society Symposia on the society’s website and Facebook page

See also his recent article in Journal of the Muhyiddin Ibn ‘Arabi Society, 59, ‘Friendship, Illumination and the Waters of Life’.

Other authors

Hanna E. Kassis, A Concordance of the Quran (University of California Press, 1983).

Bahāʼuʼllāh (Mīrzā Husayn ‘Alī Nūrī). The Hidden Words of Bahá’u’lláh. Translated by Shoghi Effendi et al. Rev. ed. Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Pub. Committee, 1954.

Bahāʼuʼllāh (Mīrzā Husayn ‘Alī Nūrī). The Seven Valleys and the Four Valleys. Translated by ‘Alī Kulī Khān. Rev. trans. Wilmette, IL: Bahā‘ī Publishing Trust, 1967.

MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE:

Finding Harmony: A King’s Vision

Broadcaster Ian Skelly, co-author of the book Harmony, talks about a new film which explores the environmental philosophy and practical achievements of King Charles III

‘We think we are suffering an ecological crisis or an environmental crisis, but at the heart of it, we’re actually suffering a crisis of perception.’

Metamorphosis: The World as Chrysalis of Soul

Sabahat Fida contemplates the implications of the caterpillar’s transformation for our understanding of identity

‘The apparent fractures and instabilities of worldly existence serve as the soil in which higher capacities take root.’

Book Review: ‘spinning pinwheels’

Gabriel Rosenstock rediscovers kokoro (heart) in a new book by the distinguished Indian poet K. Ramesh

Jethro Buck: Painting the Beyond

The renowned artist talks about the inspiration for his work in Indian miniature painting and how it can bring us into a deeper connection with the natural world

‘The way I think of art is summed up in the Alan Watts quote: “You are an aperture through which the universe is exploring itself.”’

The Kogi: More on Munekan Masha

Luci Attala talks about the recent visit of the Kogi Ambassador, José Manuel, to the UK, and the latest developments in her work with these remarkable Indigenous people

The Image Bears Witness to Your State

Psychotherapist Sir Nick Pearson talks about his unique approach to healing based on an understanding of imagination drawn from the Sufi tradition

‘The imagination is… a vital tool to help us go into the deeper aspects of life and reality or to discover our place between heaven and earth.’

Book Review: ‘Is A River Alive?’ by Robert Macfarlane

Peter Huitson reviews a book which explores the living presence of diverse rivers around the world and their power to heal and transform

The Nebra Sky Disc

Susan Bachelder is drawn into the eternal beauty of the cosmos through contemplation of its oldest surviving representation

‘There are certain things we all share, like the profound beauty of the heavens above us’

Introducing… ‘Many Beautiful Things’

Steve Scott presents a film on the extraordinary life and work of the Victorian artist and missionary, who set up a dialogue with the Sufi brotherhoods of Algeria

Social Ecology: An Alternative Perspective

Professor Jim Morley argues that we need to rediscover ourselves as naturally affiliative, cooperative and empathetic

‘We are most ourselves when we are bonding and socialising and intimate not just with ourselves but also with nature.’