SOLITUDE IN THE MODERN WORLD

The spiritual foundations of our contemporary desire for private space

by Jane Clark

SOLITUDE IN THE MODERN WORLD

The spiritual foundations of our contemporary desire for private space

by Jane Clark

Problems of loneliness and isolation are reaching epidemic proportions in Western societies, with significant consequences for both mental and physical health. The poet Marianne Moore famously observed that “the cure for loneliness is solitude”. But what is the difference between these two states? This article investigates the foundations of our contemporary desire for private space – of time spent alone with our own thoughts – in the spiritual vision of the Romantic poets and the American Transcendentalists. It reveals that the concept of solitude is at the very heart of modern life, from our love of nature to our ideas of social equality and democracy, and, most importantly, contemporary understanding of ‘the self’.

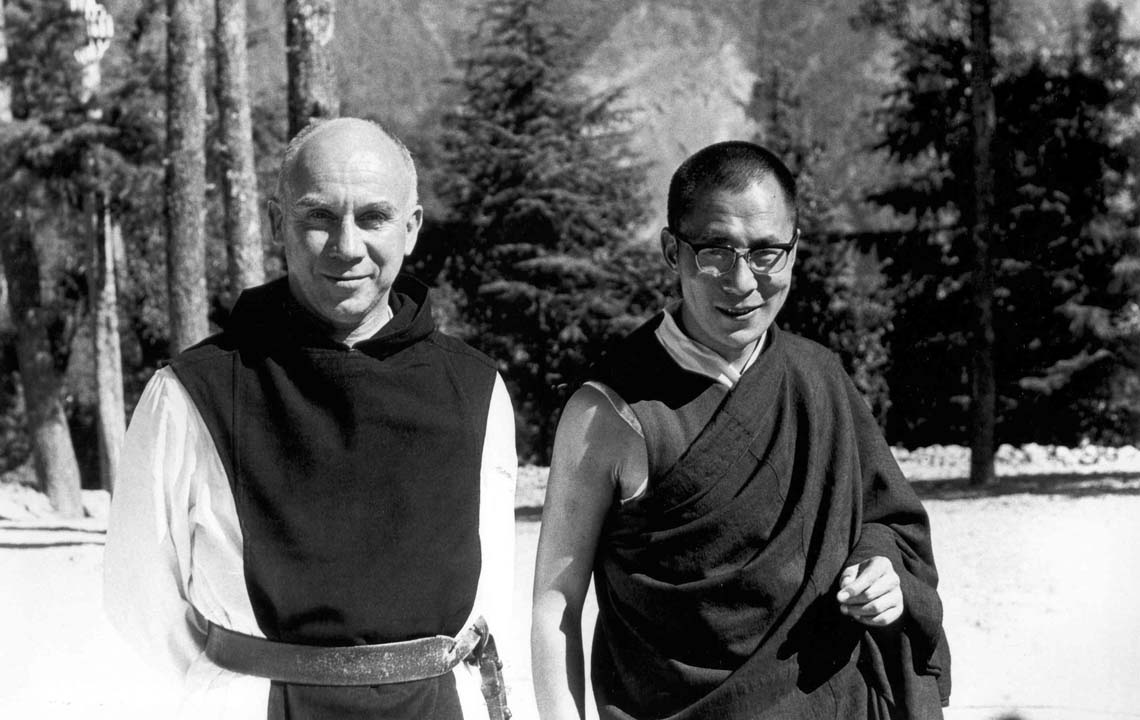

In 2015 I gave a talk for the Oxford University Centre for Continuous Education as part of a series of day schools on ‘Approaches to Mysticism’. My fellow speakers explored solitude and retreat within the context of long-established religious paths – Buddhism, Christianity, Islam – and it fell to me to talk about its importance for the many people nowadays who are not attached to any formal tradition. To do this, I found myself going back to the artists and thinkers of the 18th and 19th centuries, at the very start of what we think as the modern era, and was surprised to find how essential the notion of solitude – having a private space in which to explore our thoughts and feelings – was to the development of concepts we now see as foundational for western society: individualism, freedom, social and political equality, democracy. This article is an attempt to explore this connection in a little more depth.

In 2015 I gave a talk for the Oxford University Centre for Continuous Education as part of a series of day schools on ‘Approaches to Mysticism’. My fellow speakers explored solitude and retreat within the context of long-established religious paths – Buddhism, Christianity, Islam – and it fell to me to talk about its importance for the many people nowadays who are not attached to any formal tradition. To do this, I found myself going back to the artists and thinkers of the 18th and 19th centuries, at the very start of what we think as the modern era, and was surprised to find how essential the notion of solitude – having a private space in which to explore our thoughts and feelings – was to the development of concepts we now see as foundational for western society: individualism, freedom, social and political equality, democracy. This article is an attempt to explore this connection in a little more depth.

The contemporary importance of solitude can be quite easily seen in the way that we live now in most western societies. In traditional cultures, it was rare to be alone; people lived in close contact with one another in small towns and villages, or in small houses where parents, children

Even if we live with other people, we now regard it almost as a human right, once we reach adolescence, to have a room of our own. And this trend is extended in the age of computers and

But this is not the whole story: we choose how to use our wealth, and therefore we live like this because we see it as desirable. In previous eras, this was not at all the case. The psychiatrist Anthony Storr, whose book Solitude, published in the 1980s, is a seminal work on the subject, points out that for most people before the 19th century who were not monks or mystics, withdrawal from communal living was not seen to be desirable at all, and it was sought only in very particular circumstances, such as times of grief or illness.

At the same time, as a

One of the most famous, and perceptive, quotes about the matter comes from the American poet Marianne Moore, who said: “The cure for loneliness is solitude”. This implies that solitude is not just a matter of being physically alone; it is a state of mind, an attitude which embraces the possibilities which open up when we are away from the pressures of society.

Marianne Moore in 1953. Photograph © Esther Bubley / Science & Society Picture Library

The Bliss of Solitude

The perception of solitude and retreat as something necessary for the development of all human beings – as an essential component of a fulfilled life – came about in quite a specific way with the Romantic movement of the 19th century, when poets such as Wordsworth, Byron, Coleridge

Wordsworth Point, Ullswater, Lake District National Park. Photograph: David Noble. Noble IMAGES / Alamy Stock Photo

A good place to start is with Wordsworth’s 1804 poem, usually referred to as Daffodils – although Wordsworth himself left it untitled – describing an experience in the Lake District in the North of England. This is one of the best-known verses in the English language, and almost everyone can quote lines from it. But as with many things which are very familiar, its profound meaning is not always registered.

I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o’er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host, of golden daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

Continuous as the stars that shine

And twinkle on the milky way,

They stretched in never-ending line

Along the margin of a bay:

Ten thousand saw I at a glance,

Tossing their heads in sprightly dance.

The waves beside them

Out-did the sparkling waves in glee:

A poet could not but be gay,

In such a jocund company:

I gazed—and gazed—but little thought

What wealth the show to me had brought:

For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude;

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

There are two mentions of solitude in the poem – in the first verse and in the last. In the first line, he uses the word ‘lonely’, but not, I would maintain, to indicate the kind of alienated state of isolation of which we have already spoken. Nor should it be taken literally, for we know that his sister, Dorothy, was with him. Rather, this image of wandering and floating over the landscape without a definite goal is a metaphor, and what it denotes is freedom of thought – a state where the mind is allowed to roam untrammeled by expectation or dogma.

According to the commentator Geoffrey Watson, this notion can be traced back to the 16th-century essayist, Michel de Montaigne, who set out in his journal to examine and record his own thought processes, including every idea and emotion that occurred to him, without discriminating between them. Watson tells us that when Montaigne first published his Essais in 1580, this notion of the wandering mind was a novel one. He notes that:

Montaigne does not deny that minds need discipline too, and he often praises his father’s insistence on a rich diet of early reading and on an earnest study of ancient languages. But such disciplines need to be superseded by something wider, he believed, if they are to bear fruit. (Watson, p.350)

The ‘fruit’ that Montaigne was seeking was the thoroughly modern one of new ideas and new concepts which go beyond existing intellectual or cultural boundaries. This was also the aim of the Romantics, who specifically rejected the mediation of the church and the state in their search for truth. They were self-confessed non-conformists, longing for fresh insights and visions of grandeur which came from a realm outside that of received wisdom. Such insights can only be given by what we might call in a more theistic context ‘inspiration’, or even ‘revelation’, and they invited this by opening up the mind and letting it ‘float’ and ‘wander’ like a Wordsworthian cloud.

The ‘fruit’ that Montaigne was seeking was the thoroughly modern one of new ideas and new concepts which go beyond existing intellectual or cultural boundaries. This was also the aim of the Romantics, who specifically rejected the mediation of the church and the state in their search for truth. They were self-confessed non-conformists, longing for fresh insights and visions of grandeur which came from a realm outside that of received wisdom. Such insights can only be given by what we might call in a more theistic context ‘inspiration’, or even ‘revelation’, and they invited this by opening up the mind and letting it ‘float’ and ‘wander’ like a Wordsworthian cloud.

The outcome of such a process cannot be controlled or anticipated. It comes, as Montaigne noticed, “unexpectedly”, and thus, we find in the third line of Wordsworth’s poem:

…all at once I saw a crowd,

a host, of golden daffodils…

This image of the daffodils is so familiar now, and lends itself so readily to a chocolate-box type depiction, that it is easy to miss the fact that Wordsworth is intending to convey a dramatic and overwhelming experience which powerfully impinged itself upon his soul, creating in him a feeling, a deep emotion. So strong was its effect that it remained with him and could be evoked many years later, as he describes in the fourth verse. One could say perhaps that what was given was a taste of eternity, which, being essentially outside of time, remained accessible as an ever-fresh experience.

This evocation of an essential experience, Wordsworth implies, is a particular grace imparted by solitude. It is ‘bliss’, and this is also, according to Watson, a departure from tradition. Up until this point, introspection had most often been associated with melancholic states of mind, or with the self-deprecation of religious repentance. For the Romantics, by contrast, the kind of insights afforded by the imagination are essentially joyful and uplifting, so that we yearn to return to them. In this, they echo the writings of the mystical, rather than the merely religious traditions, where an encounter with that which lies beyond reason is also described as joy. Within Sufism, for instance, it is commonly compared to a passionate relationship with a lover, with all the bliss of union and pain of separation. The great Indian poet Amir Khusrau writes:

Which garden do you come from that your scent

is so sweet, My rose? Your breeze enlarges the

the soul, and the dead heart is brought to life.

(Ghazal 249)

The Matterhorn, Valias Alps, Switzerland. Photograph: Stephen Huwiler. imageBROKER / Alamy Stock Photo

Solitude and Wilderness

For the Romantics, solitude tended to mean withdrawal from human society in order to commune with nature, and specifically, nature in the raw – that is, wilderness. What they sought was not the aesthetically beautiful as such, but the sublime – that aspect which reveals to us the grandeur and majesty of the divine. This was what poets like Wordsworth, Shelley

Snow Storm – Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth by Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851). Photograph ©Tate Images

For Wordsworth, nature in its sublime aspect was not just an object to be contemplated. He saw it as an active force by which, through protracted exposure, our souls are educated in the higher spiritual realities until, as he puts it in his great poem Prelude, “we recognize / a grandeur in the beatings of the heart”. Unlike the tarnished and corrupt systems created by human beings, he thought of nature as a pure, sanctified source of knowledge that has the power to cleanse our souls. Thus in Prelude 12, he describes how, becoming disillusioned with the actions of his fellow human beings when he was living in London, he took refuge in nature and …

And, as the horizon of my mind enlarged,

Again I took the intellectual eye

For my instructor, studious more to see

Great truths, than touch and handle little ones.

Here there is an implicit understanding that as human beings, we need to participate in society, in human affairs, and to use our intellect and reason. But in order to keep “the horizon of the mind enlarged” so that we do not get completely caught up in petty day-to-day concerns, or “little truths”, we need to periodically return to a state of solitude and be reminded of immensity and “great truths”.

These ideas of the Romantics were echoed and expanded by their American contemporaries such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. Emerson and Thoreau were both important philosophers and essayists, members of the group now known as the Transcendentalists, who were deeply engaged in forging a new political order in 19th century America. But Thoreau is best known nowadays for his book Walden, which was a journal that he kept of a two-year experiment living alone in a cabin in the woods near Walden Pond in Massachusetts. He wrote in his Journal:

This stillness, solitude, wildness of nature is a kind of thoroughwort, or boneset, to my intellect. That is what I go out to seek. It is as if I always met in those places some grand, serene, immortal, infinitely encouraging, though invisible, companion, and walked with him. (January 7th, 1857)

The thoroughwort is a little plant, a member of the sunflower family, that is used in traditional Indian medicine to set broken bones. So here again we have an echo of the Wordsworthian idea, expressed by a man of enormous intellectual ability, that reason by itself can go astray, and become crooked like a broken bone.

A replica of Henry David Thoreau’s cabin in Walden Woods, Massachusetts. Photograph: Michael Dwyer / Alamy Stock Photo

The influence of Thoreau and Emerson had very direct consequences upon public policy in the USA, as it led to the setting up of the great National Parks in the late 19th century – Yellowstone in 1872, Yosemite in 1890. This happened largely through the efforts of John Muir, who was a passionate follower of Emerson. Such things are now an essential part of our contemporary culture; America has 59 National Parks, visited by more than 80 million people every year, and the UK has 15, including the Lake District, which alone receives nearly 12 million visitors annually. In addition, there are many smaller places which are open to the public, where we can all go and experience the beneficial and healing power of nature, and – in the face of “the unfathomable” – be brought back to “great truths”.

Hikers at Cedar Ridge, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. Photograph: Dan Leeth / Alamy Stock Photo.

Solitude, Individualism and Democracy

But perhaps the most important innovation that the Romantics brought was the idea that the sensations and emotions experienced at moments of insight, such as described in Daffodils, are important and valid – that they constitute real knowledge. This was radical in almost every sense, because unlike the learning offered by universities or kept sacrosanct within the enclaves of religion, this kind of experience does not require the mediation of external authority and is open to everyone, regardless of class, education, race or gender.

It is here that the political and social concerns of the Transcendentalists – and indeed, those of Wordsworth, who had visited Paris in the early years of the French Revolution – coincided with their understanding of the importance of the insights gained in periods of solitude. Thus Emerson begins his seminal Essay on Self-reliance with these words:

A man should learn to detect and watch that gleam of light which flashes across his mind from within, more than the lustre of the firmament of bards and sages… [So] trust thyself: every heart vibrates to that iron string.

This rallying call for every person (we should note that, as was common in his time, Emerson uses ‘man’ as a generic term for all human beings) to take control of their destiny based upon their own perceptions and conscience, was very much in the spirit of an age when both the USA and the UK were moving towards universal suffrage – i.e., the principle that every member of society, not just an educated or wealthy élite, should have a say in government.

This rallying call for every person (we should note that, as was common in his time, Emerson uses ‘man’ as a generic term for all human beings) to take control of their destiny based upon their own perceptions and conscience, was very much in the spirit of an age when both the USA and the UK were moving towards universal suffrage – i.e., the principle that every member of society, not just an educated or wealthy élite, should have a say in government.

Such ideas have of course gained great influence in the present day. But it is rarely remembered that it was absolutely intrinsic to the qualities of independent thought as the Transcendentalists originally conceived them, that they could only be achieved by entering into extensive periods of solitude; as Emerson writes:

It is easy in the world to live after the world’s opinion; it is easy in solitude to live after our own; but the great man is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude.

Solitude and the Self

The practice of solitude does not always involve immersion in nature. It can take place in the midst of everyday life by taking ourselves away from other people into our own space – to a study, a bedroom, a summerhouse in the garden. Wordsworth’s “bliss of solitude”, for instance, took place as he lay upon his “couch”, not as he was walking in the hills. Giving importance to our thoughts and feelings naturally gives rise to a desire to reflect upon them, and also to express them creatively.

Anthony Storr’s called his seminal book is Solitude: A Return to the Self, and in

Emily Dickinson’s house in Amherst, Massachusetts, which is preserved as a museum dedicated to her work. Photograph: http://www.gazettenet.com/-My-friends-are-my-estate-10067652

This aspect was particularly explored by the poet Emily Dickinson, a peripheral member of the Transcendentalist group who was admired by Emerson and corresponded with him, although she never met him personally. Dickinson lived all her life with her family in Amherst, Massachusetts, and in her final years rarely left her

There is a solitude of space

A solitude of

A solitude of death, but these

Society shall be

Compared with that

That polar privacy

A soul admitted to itself –

Finite infinity.

Dickinson referred to her self as “the undiscovered continent” and found there the “finite infinity” that the Romantics and the Transcendentalists had sought in nature. In this exploration of the “landscape of the spirit”, her observations come very close to those of mystical writers, whose most profound purpose through the ages has been to discover the divine within themselves, “Into my mind shines that which space cannot contain”, said St Augustine in the 4th century; “To know oneself is to know the divine image and likeness in oneself”, said his contemporary, St Ambrose.

So in our exploration of what it means to be in a state of solitude – rather than simply alone or lonely – I would suggest that it is to be in contact with our self in its most profound depths. This is the great opportunity presented by our contemporary access to privacy and personal space, which

Viciously, I shut the door.

The gas-fire breathes. The wind outside

Ushers in

Supports me on its giant palm;

And like a sea-anemone

Or simple snail, there cautiously

Cartoon by Simon Blackwood

NEVER MISS AN ARTICLE

Please follow and like us:

CATEGORIES

Email this page to a friend

Email this page to a friend

The first version of this article, entitled ‘The Bliss of Solitude’, was given at a day seminar at The Oxford University Department of Continuous Education on May 21st, 2016 as part of the series ‘Approaches to Mysticism’.

Image Sources

Banner: Yosemite National Park in winter. Photograph. Nicholas A. Chadwick via Wikimedia Commons

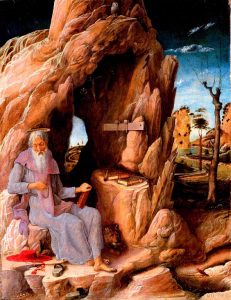

St Jerome in the Wilderness by Andrea Mantegna, 1451. Photograph: Fine Art/Alamy Stock Photo

Michel de Montaigne. Unkown artist via Wikimedia Commons

Portrait of Ralph Waldo Emerson in 1878. Image: Samuel W. Rowse [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Other Sources (click to view)

Anthony Storr, Solitude: A Return to the Self (Flamingo, 1988).

George Watson, ‘The Bliss of Solitude’, The Sewanee Review, Vol. 101, No. 3 (Summer, 1993), pp.340–51, published by The Johns Hopkins University Press; http://www.jstor.org/stable/27546732

Michel de Montaigne, Essais (Simon Millanges, Jean Richer, 1580).

All quotes from Watson ‘The Bliss of Solitude’. Amir Khusrau, The Bazaar of Love, translated by Paul E. Losensky and Sunil Sharma (Penguin, 2011).

William Wordsworth, The Prelude, 1850 version, http://triggs.djvu.org/djvu-editions.com/WORDSWORTH/PRELUDE1850/Download.pdf.

Henry David Thoreau

Journal IX: August 16th 1856 – August 7th 1857. https://www.walden.org/collection/journals/

Walden or: Life in the Woods (1854, revised edition, Penguin, 2016).

Essay on ‘Civil Disobedience’. http://xroads.virginia.edu/~hyper2/thoreau/civil.html

Ralph Waldo Emerson, ‘Essay on Self-reliance’, http://www.emersoncentral.com/selfreliance.htm.

Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own (1928 revised edition, Penguin, 2004).

Emily Dickinson, Complete Poems (1924 revised edition, Faber & Faber, 1976).

Suzanne Juhasz, The Undiscovered Continent: Emily Dickinson and the space of the mind (Indiana University Press, 1993).

Philip Larkin, Collected Poems (1988 revised edition, Faber & Faber, 2003)

NEVER MISS AN ARTICLE

Jane Clark is a teacher, researcher and editor living in Oxford. She has been involved in the study of mysticism, particularly the work of the Andalusian philosopher/mystic Muhyiddin Ibn ‘Arabī, for nearly forty years. She has given many lectures and seminars on the subject both in the UK (University of Oxford, Muhyiddin Ibn ‘Arabi Society, Beshara Trust, Temenos Academy) and internationally, and is continuously engaged in research and translation of Ibn ‘Arabī’s writings. She has a special interest in the relevance of traditional teachings to contemporary thought; she was a founder editor of The Journal of Consciousness Studies and is currently editor of Beshara Magazine.

If you enjoyed reading this article, please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

Please follow and like us:

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE:

0 Comments