Arts & Literature _|_ Issue 2, 2016

Tell Them What We Have Learned Here…

Martha Cass writes about a remarkable group of 20th-century thinkers, known as the “death-cell philosophers”

Tell Them What We Have Learned Here…

Martha Cass writes about a remarkable group of 20th-century philosophers, known as the “death-cell philosophers”

Over the past five years or so, there has been an emerging awareness of a body of work that arose during the Second World War. Fragments of it have been known for some years to disparate groups of academics and their students, but it is as if now, in the 21st century, these writings are forming themselves into a body, steadily enjoining us to give them our attention.

Over the past five years or so, there has been an emerging awareness of a body of work that arose during the Second World War. Fragments of it have been known for some years to disparate groups of academics and their students, but it is as if now, in the 21st century, these writings are forming themselves into a body, steadily enjoining us to give them our attention.

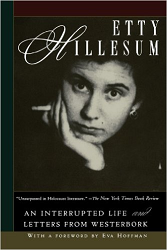

The group has become known as the ‘Death Cell Philosophers’ and includes, among others, such writers as Simone Weil, Etty Hillesum, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Edith Stein, Maria Skobstova and Corrie ten Boom, whose sister Betsie is quoted above. These people did not know each other; it is possible that Edith Stein and Etty Hillesum crossed paths at Westerbork transport camp, but if so no record of their meeting has been found. But all were concerned, in diverse ways, to document transformation as it happened to them in the crucible of mid-20th-century Europe, in the years 1932–45, and to pass on what they had learnt. The form these writings took was neither memoir in the usual sense, nor history, nor fiction; possibly the word ‘chronicles’ could help to describe these records of passage, of change from one state to another, in the context of the extreme pressure that came with the war.

People respond to pressure in many ways. What distinguishes this group of people is the resolution to be changed for the better in the context of absolute mortal threat – leading them in some cases even to forfeit the chance to escape it. As Rowan Williams has put it, these people were concerned with “the discovery of a real and completely, powerfully transforming divine faithfulness, present even in the depths of the nightmare…”.

To discuss properly all of the writers I have mentioned above would be impossible in the scope of this short article, so I propose here to concentrate on two of them – Simone Weil and Etty Hillesum. Of the six philosophers above, these two participated most explicitly in what Dom Sylvester Houédard of Prinknash Abbey would later call ‘the wider ecumenism’ – a phrase coined to describe a contemplative stance that, while respecting the metaphors and lived experiences of particular faiths, is not constrained by their boundaries.

The writings of Simone Weil are in some ways the least related to the circumstances of the war, as she did not experience the camps herself – in fact, she may have died before their existence was fully known. Nevertheless, paradoxically, a thread of mortal pressure runs right through her work, and gains strength as the war progresses. This pressure was created not by Weil’s proximity to the Nazis, but, outwardly, by her distance from the fight against them, and inwardly, her distance, as she felt it, from what she considered to be grace.

Simone Weil was born in Paris in 1909 to a Jewish agnostic family; in secondary school she studied with the philosopher Emile Chartier, aka Alain, and was one of his most brilliant students. After university she embarked upon a teaching career, and also spent time as a manual worker in a Renault factory to gain first hand experience of the privations of working people at the time. Her notebooks also contain wonderful accounts of two trips to Italy, where her focus begins to change towards her own kind of Christianity. This was deeply influenced, as it continued to be in the coming years, by her engagement with the Bhagavad Gita, the Zen Teachings of Daisetsu Teitaro Suzuki and the English mystical poets, particularly George Herbert.

Simone Weil was born in Paris in 1909 to a Jewish agnostic family; in secondary school she studied with the philosopher Emile Chartier, aka Alain, and was one of his most brilliant students. After university she embarked upon a teaching career, and also spent time as a manual worker in a Renault factory to gain first hand experience of the privations of working people at the time. Her notebooks also contain wonderful accounts of two trips to Italy, where her focus begins to change towards her own kind of Christianity. This was deeply influenced, as it continued to be in the coming years, by her engagement with the Bhagavad Gita, the Zen Teachings of Daisetsu Teitaro Suzuki and the English mystical poets, particularly George Herbert.

But eventually, of course, the Weil family’s lack of engagement with formal Judaism did not prevent them from being forced to leave Paris in 1940. After a period in Marseille, in which Weil developed important friendships with the philosopher Gustave Thibon and Fr J.M. Perrin, she accompanied her parents to New York. Immediately upon arrival she began petitioning to be allowed to return to England, which she did in 1942, working with the Free French in London until her death in 1943 at a sanatorium in Kent. The cause of death was tuberculosis exacerbated by her lifelong habit of eating little; this practice had intensified with the war, and her decision to eat no more than the French troops were allowed.

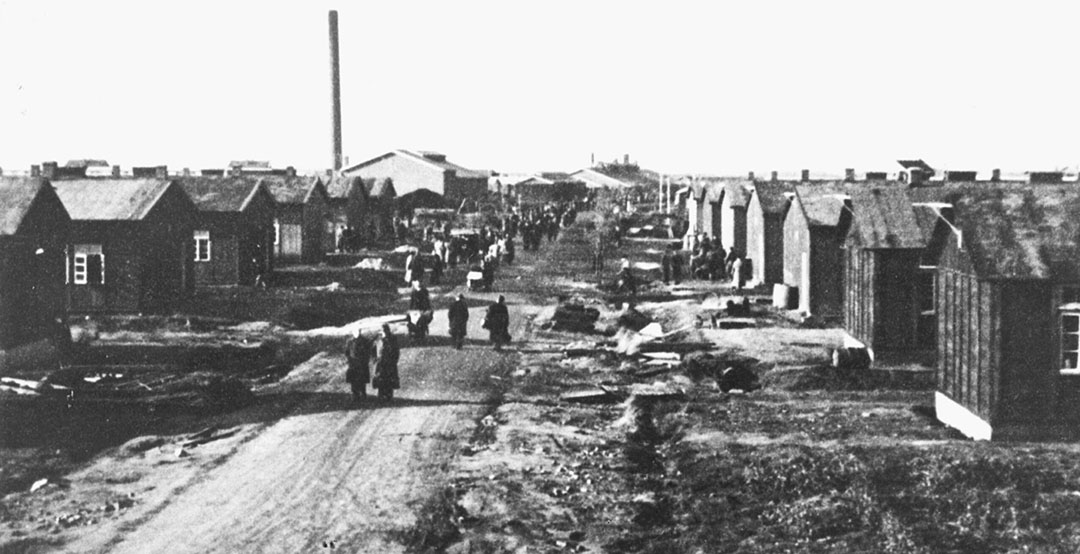

During this intense period of her adult life, she filled many volumes of notebooks, and wrote stringently beautiful essays and letters chronicling the burnishing of her political, and then her interior self as she worked and travelled. But one of her particular gifts – both given and cultivated – was in her conviction that focus, or attention, is the most valuable asset possessed by any human being, and that prayer, whatever one hopes for it, consists of it. She writes in one of her best-known collections of writings, Waiting for God:

Prayer consists of attention. It is the orientation of all the attention of which the soul is capable towards God. The quality of the attention counts for much in the quality of prayer. Warmth of heart cannot make up for it.

She has much to say about this, meticulously set out in her essay, Reflections on the Right Use of School Studies With A View to the Love of God, a wonderful exposition of the theory and method of undivided attention, without boundaries as to where it might be practised or found. For Weil, this marshalling of all of the ‘self’s’ forces – physical, metaphysical, intellectual, spiritual – was crucially important. Having begun her career as a teacher of philosophy, she had devoted much thought to the relationship between student and text, and how this could develop the capacity fully and lovingly to give attention, whether to a piece of writing or the suffering of another person. Difficulties with learning, or even failure in it, for Weil, are immaterial, and lack of aptitude “almost an advantage”:

Never is a genuine effort of the attention wasted. It always has its effect on the spiritual plane and in consequence on the lower one of the intelligence… Without our knowing or feeling it, this apparently barren effort has brought more light into the soul. The result will one day be discovered in prayer.

She brought her own intensely cultivated power of attention to bear upon particular texts in a way that for her was absolutely transformational. The most notable instances of this were her contemplation of Herbert’s poem ‘Love’, and her daily focused recitation of the ‘Our Father’. Her efforts and experiences are recorded in essays and ‘pensées sans ordres’ collected from her notebooks and published articles.

Etty Hillesum (1914–43), by contrast to Weil, was directly in the line of fire during the war. As a young woman coming of age in Amsterdam, she pursued studies in Russian language and literature, living a rather chaotic and emotionally turbulent life, until that path was cut off from her by the occupation and the strictures imposed upon Jews by the Nazis in the period 1940–43. However, as the situation worsened she found herself among a group of friends and colleagues who valued education, books, art, and – for want of better words – ‘the inner life’. She began a transformative friendship with the figure central to the group, Julius Spier, who had been a colleague of Jung. Her interior resources were strengthened and deepened, recalling, when she resolved “to regulate my life”, the diary entries of Claudine Moine, hundreds of years before, in the midst of another war.

Etty Hillesum (1914–43), by contrast to Weil, was directly in the line of fire during the war. As a young woman coming of age in Amsterdam, she pursued studies in Russian language and literature, living a rather chaotic and emotionally turbulent life, until that path was cut off from her by the occupation and the strictures imposed upon Jews by the Nazis in the period 1940–43. However, as the situation worsened she found herself among a group of friends and colleagues who valued education, books, art, and – for want of better words – ‘the inner life’. She began a transformative friendship with the figure central to the group, Julius Spier, who had been a colleague of Jung. Her interior resources were strengthened and deepened, recalling, when she resolved “to regulate my life”, the diary entries of Claudine Moine, hundreds of years before, in the midst of another war.

It is difficult to choose which passages from her diaries to include in this short article, as they are best appreciated in the full context of her life. Patrick Woodhouse, whose book Etty Hillesum: A Life Transformed is the most complete account of her life to date, summarises it as follows:

What is astonishing is that in just two years – despite all that was happening around her – she succeeded in breaking through to an altogether deeper dimension of living. She went on to explore and develop an inner life of such depth and richness that not only was she sustained through the hell of the transit camp [Westerbork, where Dutch Jews were taken before being sent further east], but she became a luminous figure to those who knew her and for whom she cared in the camp. She was a vital, life-giving presence…

Etty writes from Westerbork:

At night I lay in the camp on my plank bed surrounded by women and girls, gently snoring, dreaming aloud, quietly sobbing, tossing and turning, women and girls who often told me during the day, “We don’t want to think, we don’t want to feel, otherwise we are sure to go out of our minds.” I was sometimes filled with an infinite tenderness, and lay awake for hours…and I prayed, “Let me be the thinking heart of these barracks.”

She had by that time already resigned from the quite natural condition whereby anger, fear or hatred of their oppressors could secure a foothold. She essentially thought that these were a waste of time, and got on with the business of gratitude, writing in the winter of 1942:

It’s happened to me a few times recently – in the street or wherever I chance to be, I stop with bated breath for a moment and have to ask myself, is this really my life? So full, so rich, so intense and so beautiful?

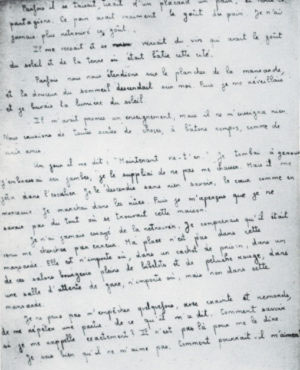

She was not forcibly detained at Westerbork but had a certain amount of freedom of movement through a job she had taken in Amsterdam with the Jewish Council. Her friends urged her to make her escape, but she did not. She stayed where she was, moving between the camp and her flat in Amsterdam until she and her family were sent to Auschwitz in 1943, finishing her diaries with the words: “We should be willing to act as a balm for all wounds.” Astonishingly, a postcard that she threw from the transport train as it departed, was picked up by a farmer and sent to its intended. “We left the camp singing”, she wrote.

Postcard sent by Etty Hillesum as she left on the train to Auschwitz. Photograph from the collection at the Jewish Historical Museum, Amsterdam

Her letters and diaries are, in my view, required reading for anyone wishing to learn about – and, more aptly, from – those years.

The pressures of the 21st century are of course markedly different from those of the 20th but it is becoming clear that the Death Cell Philosophers’ strategies for dealing with adversity, including the most extreme, can be of enormous help to us now. Their individual resolutions to be positively transformed in the face of oppression, and their efforts to rally all of their interior faculties to the cause of loving service, may indeed serve as models for us, as we enter the next phase of the digital age.

Sources (click to open)

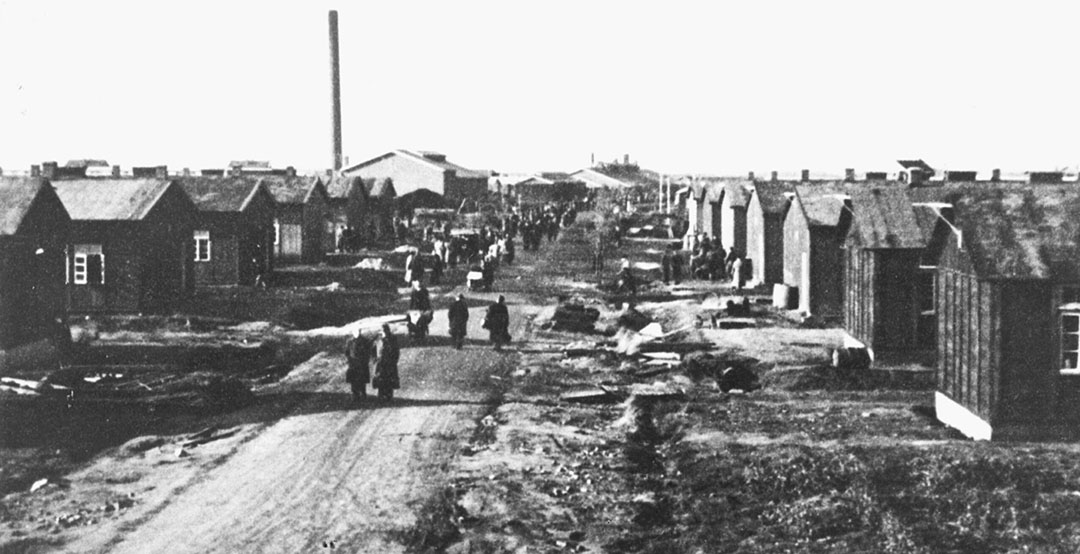

Main image: Westerbork Transit Camp. Photograph from BeeldBankWO2.

Article Thumbnail: Jewish prisoners boarding the train to Auschwitz from Westerbork transit camp. Photograph from BeeldBankWO2.

Our thanks to Beedlebankwo2 for images of Westerbork Transit Camp; to the Jewish Historical Museum of Amsterdam for material on Etty Hillesum. For the Simone Weil material we have not been able to trace copyright holders, but if we have inadvertently overlooked them, we will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Published works

Etty Hillesums’s diaries have been published in English in full, combining in one volume An Interrupted Life (Diaries 1941–43) and Letters from Westerbork, translated from the Dutch by Arnold J. Pomerans (Henry Holt & Co., New York, 1996). These two can often be found published separately.

Etty Hillesums’s diaries have been published in English in full, combining in one volume An Interrupted Life (Diaries 1941–43) and Letters from Westerbork, translated from the Dutch by Arnold J. Pomerans (Henry Holt & Co., New York, 1996). These two can often be found published separately.

The quote from Rowan Williams comes from his Foreword to Patrick Woodhouse’s Etty Hillesum: A Life Transformed (Bloomsbury, 2009).

For Claudine Moine, see You Looked at Me: The Spiritual Testimony of Claudine Moine. Trans. Gerald Carroll (Clarke & Co, Cambridge, 1989).

Some of Simone Weil’s most essential writings can be found in Waiting for God, translated by Emma Craufurd (Putnam & Sons, 1951); Gateway to God (Fontana, 1971); Intimations of Christianity Among the Ancient Greeks (Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1957); Gravity and Grace (Routledge Classics, 2002); War and the Iliad (NYRB Classics, 2001); Letter to a Priest (Routledge Classics, 2002).

Her political writings include: The Need for Roots (Routledge Classics, 2001); Oppression and Liberty (Routledge Classics, 2002). Her Oeuvres Complètes has been been published by Gallimard, and she is widely anthologised.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer is best known for his Letters and Papers from Prison (SCM, 1953). His other works include Life Together, The Cost of Discipleship, and Ethics, all of which have recently been reprinted.

Maria Skobstova and Edith Stein are both profiled in the Modern Spiritual Masters series, published by Orbis.

Corrie ten Boom’s experiences were chronicled in The Hiding Place (Hodder & Stoughton, 2004).

For more on Dom Sylvester Houédard’s ‘wider ecumenism’, see Charles Verey, ‘Dom Sylvester’s ‘Wider Ecumenism’: Considered Words, Explosive Meaning’, in Notes from the Cosmic Typewriter (Ed. Nicola Simpson, Occasional Paper, 2012).

Email this page to a friend

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.