Arts & Literature — Issue 5, 2017

An Artisan of Beauty and Truth

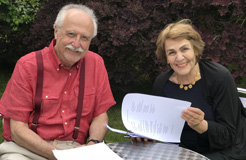

Etel Adnan in conversation with David Hornsby and Jane Clark

An Artisan of Beauty and Truth

Writer and artist Etel Adnan in conversation with David Hornsby and Jane Clark

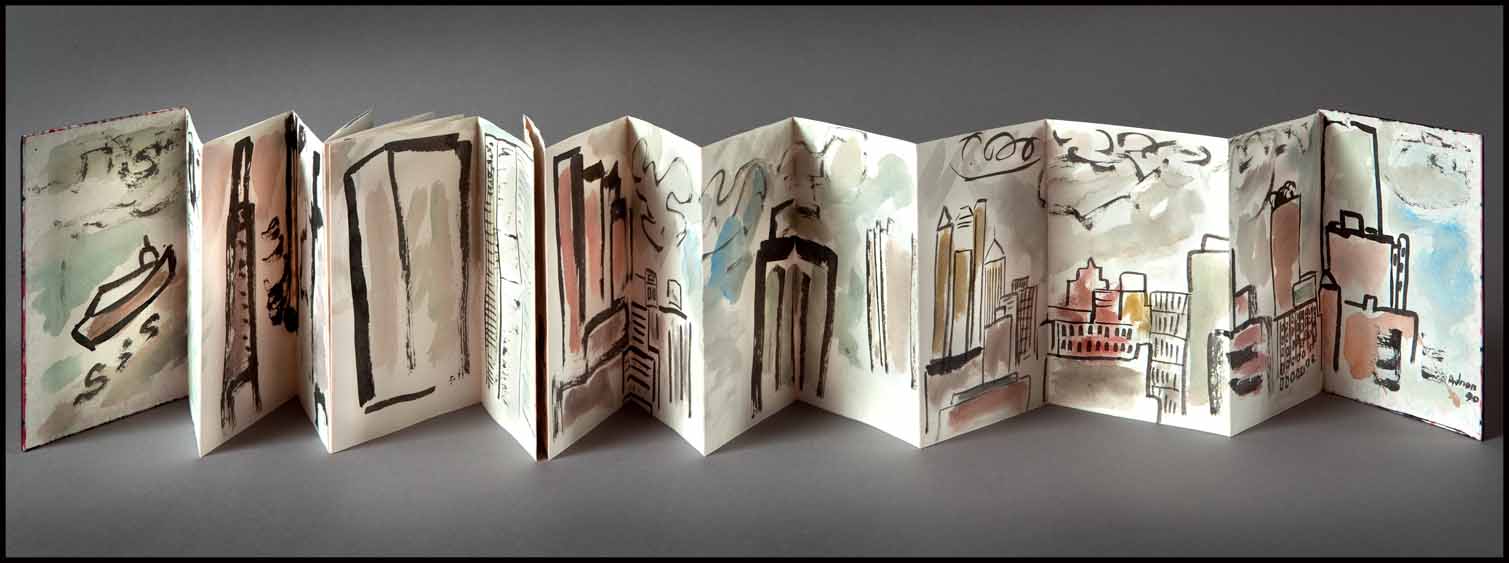

Etel Adnan has excelled in a remarkably diverse range of fields during her long life. She is a poet, known in particular for her protests against the Vietnam and Iraq wars; a novelist whose book about the Lebanese civil war, ‘Sitt Marie-Rose’, won the coveted France-Pays Arabes prize and is considered a classic of war literature; a journalist and essayist who has explored the nature of place and history in books such as ‘Of Cities and Women’, and ‘Paris When It’s Naked’; and a philosopher who taught for many years at Dominican College in California. Now in her early 90’s, she is receiving widespread acclaim for her artistic work, and during the last year has had major exhibitions in London and Paris. In this, also, she shows mastery of a wide range of genres, producing tapestries and ceramics as well as paintings and drawings, and pioneering the development of leporellas, or folding books, based on the Japanese traditional form.

Hans Ulrich Obrist, Artistic Director of the Serpentine Gallery, has called her “one of the world’s great poets and artists”. She calls herself – according to the artist and publisher Simone Fattal – “an artisan of beauty and truth”, maintaining that: “Every art is a window into a world that only art can access. You can’t define these worlds. They are epiphanies, visions.” We visited her in the flat in Paris where she now lives and still works, and talked to her about her life, her art and her long-standing connection with the great mystical metaphysician, Muhyiddin Ibn ʿArabī.

David: The last time I saw you was in 2010 at the Serpentine Gallery in London, where you were reading some of the poetry which you had written about the Iraq war.

David: The last time I saw you was in 2010 at the Serpentine Gallery in London, where you were reading some of the poetry which you had written about the Iraq war.

Etel: I remember the event. It was in one of their temporary pavilions, the red one done by Jean Nouvel [/]. Every year they commission a new building, and then take it down at the end of the season. This one I remember as being like a dream – it was all red and shiny with the green summer trees outside. The poem is called “To Be in a Time of War [/]”. It appears at the end of the book In the Heart of the Heart of Another Country which came out in 2005 in San Francisco, published by City Lights. The whole poem is written in the infinitive:

…To wake up, to stretch, to get out of bed, to dress, to stagger towards the window, to be ecstatic about the garden’s beauty, to observe the quality of the light, to distinguish the roses from the hyacinths, to wonder if it rained in the night, to establish contact with the mountain, to notice its color, to see if the clouds are moving, to stop, to go to the kitchen, to grind some coffee, to lit the gas, to heat water, hear it boiling, to make the coffee, to put off the gas, to pour the coffee, to decide to have some milk with it, to bring out the bottle, to pour the milk in the aluminum pan, to heat it, to be careful, to pour, to mix the coffee with the milk, to feel the heat, to bring the cup to one’s mouth, to drink, to drink again, to face the day’s chores, to stand and go to the kitchen, to come back and put the radio on, to bring the volume up, to hear that the war against Iraq has started…

I did this because I was brought up in the Middle East, in Lebanon, but when the Iraq war began, I was living in America. When you are not a native to a country, in time you can pretty much come to feel integrated. But when it comes to a crisis somewhere back home, or near home, then you realise that you lead a double life. You can carry on with your everyday routines, but something is hurting you that is totally without interest for other people.

Untitled, ca. 1995–2000; Oil on canvas 40 x 50cm. Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburg / Beirut, and Serpentine Galleries

David: You are now 91 and have lived in many countries during your life – Lebanon, America, France, Britain. Did you also spend time in Iraq?

Etel: No, I never lived there. But I once participated in a group show in Baghdad. At that time, the Iraqis had the most alive, the most exuberant culture of all the Arab countries. It used to be said: “They write a book in Beirut, they print it in Cairo, but they read it in Baghdad.” When I went to Baghdad in 1976 for this show, there was a party in which all the young men stood up and recited by heart my poetry, which had been translated into Arabic. I was amazed that they knew it. Of course, if you criticised Saddam Hussain you were dead, but if you didn’t, the rest of the country was working – and it was, as I just said, exuberant. When the war happened, I knew that they would erase this culture, and of course they did. So I was very sad. But my American friends couldn’t care less.

David: It is striking that during the Vietnam war, there were very many American poets who complained about the war and criticised it, but when it came to the Iraq war, you were one of very few voices who spoke eloquently against it.

Etel: I think one reason is that during the Vietnam war, the young people did not want to go and fight. So after that, the government – governments all over the world – stopped the compulsory draft into the army. Also with Iraq, they demonised Saddam and so made it a ‘good war’. And of course it was far away. Some senators of the American government did not even know where Iraq was on the map!

David: Do you think that this sense of being between two cultures, and of tension or conflict between them, goes back to your childhood and your upbringing in Beirut?

Etel: Well, my father was a Turk and a Muslim, and my mother was a Greek and a member of the Greek Orthodox Church, at a time when intermarriages were not common at all. He was a top officer and a classmate of Atatürk; they were at the military academy together. My father was already married with three children when he met my mother; he lived in Damascus and had his first family there. My mother was twenty years younger, and I was the only child of their marriage.

There was not really any conflict at home. My parents did not try to convert each other, and they did not speak about religion much. He was a Muslim, but he was not very strict in terms of practice. He did not do Ramadan, for instance, and so she did not have to deal with that. Contrary to what is thought these days, Muslims then did not have many practices; they would only go to the mosque every now and again.

But there was some conflict in society. At that time, Christians and Muslims did socialise, but marriage was not really allowed. I went to a Catholic school, because all the schools were Catholic, and they were sponsored by the French government. The nuns on a number of occasions told poor little Etel that everything was all right with her except for her Muslim father. This puzzled me. Some of the other children would also say things. “Your father is a Muslim! How come?!” So I was aware in a subdued, or very private way, of tension. This became more overt in 1948 with the creation of Israel. I was no longer a child of course then – I was 23 years old – but I was not very politically aware until I went to America at about the age of 30, in 1955. Then I met students from all over the world, and became politicised.

David: How do you think that you have expressed this awareness of conflict in your art?

Etel: I have not really done this in my art, more in my writing. Art is abstract by nature; it is colours and shapes. And also, art has a certain sort of energy. Even if it is black, there is a way in which it is happy. But words are social; you cannot run away from their meaning. Of course art can portray tragedy – Picasso painted Guernica, so it can certainly be done. But when I paint, I am always happy to start with.

With words I am more aware of other things, like history. I was born in 1925, which was very close to the end of the Ottoman Empire. It finished officially then, but in people’s lives, something like that takes a generation to end. It is the same way when you lose your father; he died on a certain day, but all your life you may be haunted by that. For my father, the Ottoman Empire was his world, his job, his life. He was only 38 when the First World War ended, so by the age of 40 he was an unemployable man. From that point onward, he hardly spoke a word. My mother had been born in Smyrna in 1898, so at 24 her world had also disappeared, and she went to live in Lebanon. For some people the French seemed like liberators, but for both of my parents Lebanon was an occupied country ruled by the French. So I grew up with people who were defeated when they were still young.

Jane: But it seems that you were not defeated.

Etel: A child has a kind of energy. And you can change topic all the time. You can be in trouble, they spank you, you cry; then they give you cake at noon and you cheer up. A child does not drown in a single problem, unless of course they are beaten very badly or are very hungry, etc.

David: There is wonderful line in one of your works about the light that shines on a child when they are aged between about four and six.

Etel: I was very aware of the beauty of the world, because I was a lonely child. I was not distracted by brothers and sisters, so I was more aware of my environment. We had a garden when I was very small, and I would look at flowers. Even the shape of an egg or a knife would entrance me. We also had a dog, and I was very much aware of what the dog was doing. I saw that he used to look at himself in the mirror. We had these very big mirrors on the cupboards, and as a child I was often in front of the mirror, talking to myself. So I thought that he was doing something like me.

Leporella (From Laura’s window), New York, May 23, 1990. Watercolour, ink. Cover: 18.3 x 12.3 cm; maximum extension 264cm. Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburg / Beirut, and Serpentine Galleries

On Painting and Falling in Love with a Mountain

.

David: Going back to your painting – you had your first UK exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery last summer. How did that come about?

Etel: The Director of the Serpentine, Hans Ulrich Obrist, had seen some of my paintings in a small gallery in Paris, and he had been attracted to them. Then in 2011, I had a show in Beirut in a big gallery, the Sfeir-Semler [/]. This was a very large exhibition, almost a retrospective, and it led to my being invited to the Documenta [/] exhibition which takes place in Kassel, Germany every five years. This has such fame that it attracts curators from all over the world. So after that, I was approached by very many galleries. I had to turn down many of them – sometimes because I did not want to do three shows in the same town! But I did the one at the Serpentine [/], and then one at the Institut du Monde Arabe [/] in Paris, which has just finished.

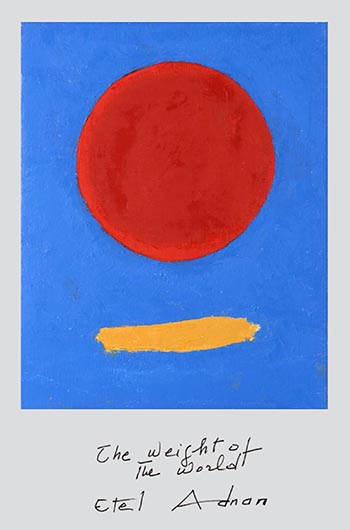

David: The Serpentine exhibition included a series of new works called ‘The Weight of the World’. Why did you choose this title?

Etel: One day I made a big circle, huge like a full moon, on a small canvas. I felt the weight of that circle, and it reminded me, among other things, of the world. Hans Ulrich happened to be here in my flat in Paris, and it was he who suggested that I make a series for the London exhibition. My paintings are not usually titled. Art should make people dream, and when you have a title, you condition the vision. But people like titles, so I gave one for these paintings.

David: In writings, you give various meanings for this ‘weight’. Sometimes it is sadness, sometimes conflict, sometimes atomic disharmony, sometimes freedom. In each of the paintings, with the way you use colour and such like, it takes on a different meaning.

Etel: You are right; the circle is whatever the world brings. It is the world in the total sense, the world that we live in. The first thing that occurs to me is that the world is chaotic, and the second thing is that there are conflicts within it. We are also sentimental; we always want to think that the world was a better place in the past. But this is an illusion. The world has always had wars and turmoil. I think that materially, the world is not as bad as we think it is; of course we have problems, but in general there is no famine; we have medicine, good or bad; we have government, good or bad. When you listen to the news it is always murder in Latin America, an earthquake in Japan, the death of a young singer in Paris. But they don’t tell you how the seven billion people who are in the world actually live. Most of them are living quite normal lives.

The Weight of the World; the whole series of 20 images at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery, London (2 June–11 September 2016). Photograph © Tristan Fewings/Getty. Courtesy of Serpentine Galleries

David: You have said that you always start a painting with a red square.

Etel: It is something to lean on when I first begin a painting. I don’t start with an image, so I have to start with something. There is nothing particularly profound about my reasons; when I first began painting, I did not use a brush but a palette knife. A knife works horizontally, and what it does naturally is a rectangle or a square.

David: When you begin, do you have an idea in your mind of what you wish to express?

Etel: There are different moments. When I paint a mountain, then I know that I am going to do a mountain, and it is basically triangular. But you discover as you paint; you build the painting. Although there is always some direction. When I paint the mountain, the direction is very clear; it is my love, and my sense of the importance of that mountain. When I do abstract shapes, it is more to do with energy. Someone like Jackson Pollock paints his energy, and that is a direction. Rothko paints the shimmering of light, and that is also a direction.

Jane: By ‘the mountain’ you mean Mount Tamalpais in California, which you have described falling in love with?

Etel: Yes. When I went to California I knew nobody, and I started teaching at the university in Marin County, where there is a single mountain – I mean a mountain that is not part of a chain. It is not so high, only 3000 feet, but it uplifts the whole area. It is like a totem pole, something you see from afar, and every time I saw it I felt at home; it replaced home, it created home, and it’s a beautiful thing. So whenever I moved around in the car or went to San Francisco, I felt secure.

This was also the first time I felt face to face with something so powerful and enormous. In the USA you are very mobile and use the car all the time, and so your environment constantly changes. So the mountain is always there, but at the same time it is never the same. It’s like a mystical experience. It arrives in your mind, it stops you but also has no stopping, and its effect has no total explanation. It amazes you by just being.

Etel Adnan; Untitled, ca. 1995–2000, oil on canvas 35 x 45.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburg / Beirut, and Serpentine Galleries

David: This was around the time when you first started painting?

Etel: Yes. One day, I met the head of the art department at the University, Ann O’Hanlon, and she asked what I taught. I told her that I was teaching the philosophy of art. So she said: “Are you a painter?” When I said, “No,” she asked: “But how can you speak of something you don’t know?” My answer was: “But my mother said that I was clumsy.” It is funny that, at the age of thirty, this was the answer that came. My mother was very impatient with me when I was a child, and if I could not do things quickly she would not let me do them. But Ann’s response was: “And you believed her?” And that sentence freed my head.

She invited me to the art department, and gave me a set of little pastels, and I started using them. Then some months later she gave me canvases cut with scissors, a palette knife and some little ends of tubes, and said: “Go ahead. You are a natural painter; you don’t need charcoal.” Her philosophy of art for her students was to have them ‘find themselves’. That was basically the American method.

Jane: One of the things that you said about these early paintings is that you ‘painted in Arabic’, which was not your native tongue. You spoke Turkish and Greek at home in the Lebanon, and French at school.

Etel: I started painting at the time of the Algerian war. I was so outraged by the things that the French were doing that I said: “I am not writing in French any more”. But I was not yet writing in English; I was teaching in English, but I was not writing seriously in it. That would come later, when I started to write poetry. So I signed my name in Arabic on the paintings. It was my gesture of dissent.

I never went back to French. Since about 1963, when I was writing poetry about the Vietnam war, I have always written in English. The only exception was a couple of years when I was living back in Beirut, and then I did it only because of the environment and the people I was meeting there. It was there that I wrote the book Sitt Marie Rose about a woman who gets caught up in the civil war.

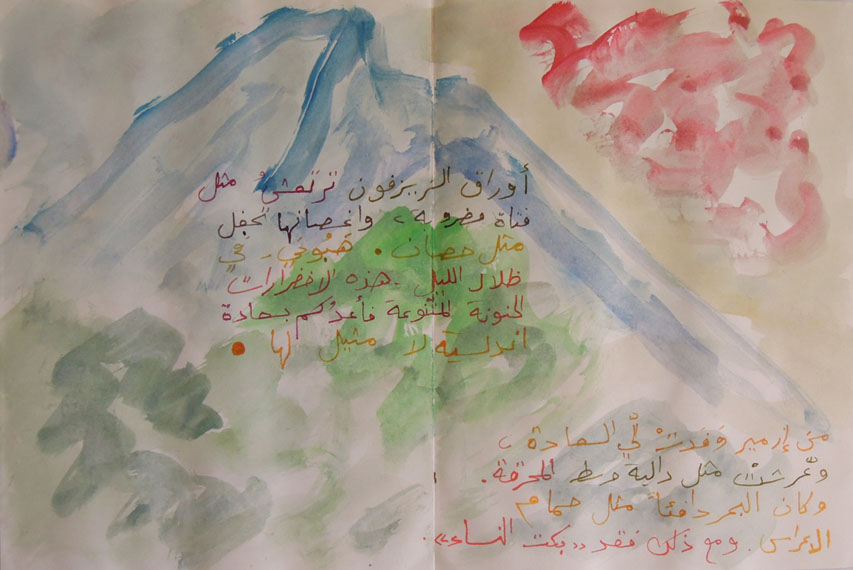

Zayzafouna (The Linden Tree): a poem by Etel Adnan. 1985. Watercolour and indian ink on Japanese book. Closed, 24.5 x 18cm x 30 pages. Open, 24.5 x 540cm. Private Collection, Lebanon. © Etel Adnan. Courtesy of Galérie Claude Lemand, Paris

David: It is extraordinary that you have successfully practiced in three different areas of art – poetry, literature and painting.

Etel: I discovered poetry aged 20 and have been hooked ever since. I get impatient with novels. Poetry says things you can’t pin down, so you are never through with a good poem. I came to art, as I have just explained, by chance, through meeting Ann O’Hanlon. Her philosophy was that we can all paint or do music, like we all speak to each other. They are languages. We are not all Shakespeare or Picasso, but we can write and we can paint. This approach is very good because it doesn’t scare people. You can’t start by comparing yourself to a finished work of Rembrandt, but if you start doodling, little by little you may like what you do and go ahead, or you may be bored and say it’s not for me.

Jane: You yourself have often referred to painting as a kind of language.

Etel: Of course. There are many languages which are not made of words. Language is a means of expression, and everything can be an expression, even the way we look at an object. But these other languages are mysterious, because we are used to a word culture; we are not really a visual culture. So we have a tendency to favour word-based languages, and we think that we understand best when we can put things into words. But this is cultural; it is not biological.

In fact, understanding is not meant to be wordy; we feel, and there is a leap between what we call knowledge and feeling. So music and dance are mysterious languages because they say something but they are not meant to be put into words. Maybe we even destroy them when we over-explain. They are meant to be absorbed. My students used to ask me: “What is abstract painting? Is it just lines and shapes?” And I would say: “No. The meaning is communicated by lines and shapes, but there is more, and we don’t understand this ‘more’ 100%.” But we feel it, and we should just accept that.

Jane: We have just published an article in the Magazine which is an appreciation of the cave paintings at Chauvet in the South of France, which are about 35,000 years old. These make it clear that painting is very deeply connected to our understanding of ourselves as human beings.

Etel: The cave painters were superior to us. No painter – neither Picasso, nor Rembrandt, nor Raphael, nor the Japanese – has ever painted bison and horses and cows like the early cave painters. Their paintings are alive, because these people were animists – they dialogued with the animals, like the American Indians did. For them, the bison was an equal – equal and different; it was not that the Indians were better because they were human beings. When they ate meat, they never killed for killing’s sake and they thanked the animal – “So that we become one with you”. They had a great wisdom there. If the American people had listened to the Indians instead of slaughtering them, they would have been a much more interesting culture!

You see, to paint is not just a skill. It’s a moment of communication with whatever you are painting. And if you have that strength, that deep natural conviction, that the bison is as important, if not more important than you, then you can paint it. But if you think he’s just a shape, then you just make a shape. Matisse made shapes, but a lot of Matisse’s women are lifeless. The colours are beautiful because he liked colours, but often it’s just a line, empty; it doesn’t touch you. I think he liked ribbons and clothes more than women! Certainly Cézanne liked the Mont Sainte-Victoire more than his wife. She is wooden in his paintings, but the paintings of the mountain are alive.

There are a very few human portraits that I like. I like Rembrandt: his self-portraits are tragic like his life. Compare a flat Matisse woman and a portrait by Rembrandt and you can see the difference in range.

Cave paintings are the greatest accomplishment in visual art. You are flabbergasted. The animal is there. Present. That is because he was so for the person who drew him. They had a relationship. We don’t have strong relationships these days; we are too busy in our lives. Even when we speak of God and love and all that, it’s very divided because we have very dispersed lives.

The writing desk in the flat in Paris. Photograph by Laurène Mercier.

On Spirituality, Love and Ibn ‘Arabī

.

Jane: Speaking of God and love and all that – you were educated at a Catholic school, but you have said that you were not particularly influenced by what you were taught there; what interested you, always, was revelation.

Etel: It is maybe strange, but even as a child, I was never afraid of God. For instance, I never believed in hell. Heaven always made sense, and even today the idea of Paradise interests me. But the idea of hell never made sense to me as a child, and I have not changed my mind. Now of course I can explain this to myself philosophically, because if God knows everything, His judgement is not the same as our judgement. Our judgement is partial; when someone commits a crime, we don’t know whether they were really responsible or not; were they really crazy at that hour or not? We have to judge them according to our social laws, but if God knows it all already, He cannot judge.

One of my students asked me: “Do you believe in God?” And I found myself answering: “I do, but I don’t know what it means”.

Jane: Later on, though, you were involved in the study of the Islamic mystics such as al-Hallāj and Jalāl al-dīn Rūmī, and also read the works of Ibn ʿArabī.

Etel: I got in touch with Ibn ʿArabī [/] when we lived in California, mostly because Simone Fattal, my friend, was very seriously involved in studying and publishing his work [/] – and still is. I did not read his work in a systematic way; it just happened. One of the greatest moments was when we read the famous summary of his metaphysics, The Twenty Nine Pages [/], with a group of people in California. We read it in one breath.

Jane: What is it that intrigues you about him?

Etel: I feel that his thought is very close, as a procedure of the mind, to oriental music – the music of Ali Akbar Khan, or Arabic classical music, which is based on theme and variation. There is a basic theme in Ibn ʿArabī with infinite little variations. He is like a man who turns around a point, a pole, to which he constantly returns. This pole he calls God.

Or you could say that he is like somebody that a wave brings to the shore, and then the same wave takes him back, and then brings him in again, and so on. The wave keeps rolling, and every rolling is a new experience of what is maybe the same thing. This is the great mystery which Heraclitus and Parmenides pointed to – the mystery of constant change. But what is it that we think changes? We are in a constant change. But what’s changing?

A basic problem in Western thinking is a misunderstanding of Aristotle. Aristotle divided things into categories for pedagogical reasons, to put order into thinking, but Western thinking made of each category a separate attribute. This is a basic mistake. For example, my hand and foot are not the same; when my hand hurts it is not my foot, and when they operate on my hand they don’t look at my feet. But hand and foot are nevertheless part of a continuum. So these categories are helpful to our thinking, but they were never intended to be existences in their own right, and separated. Reality is not separable.

So there is a problem with what I call ‘hard shell’ separation. In what we call the monotheistic religions, we have an interesting situation. We want God to be close to us, and we also want Him to be separate. He is so ominous that we have to separate Him; we can’t imagine that we measure up to God. On the other hand, a totally separate God would be meaningless. So we have in monotheism the mystery of togetherness with God, and at the same time separation from Him, and within this question all mysticism moves.

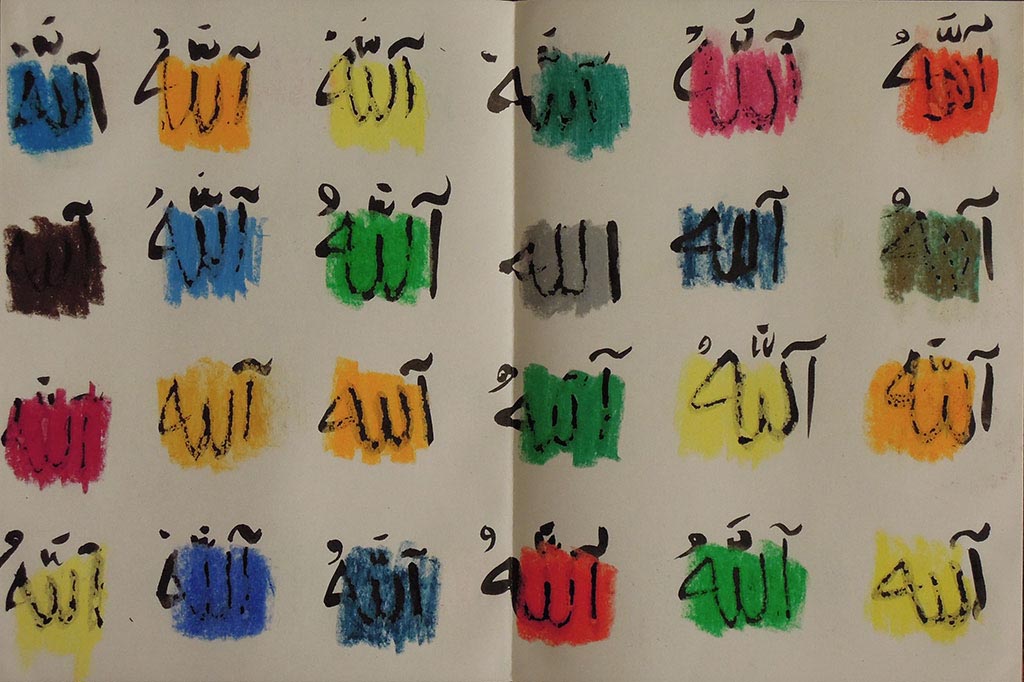

Zikr, 1998. Ink on Japanese book. Open, 24 x 540. Private Collection. © Etel Adnan. Courtesy of Galérie Claude Lemand, Paris

Jane: Do you think that one of the problems is that we make God into a separate transcendent being?

Etel: By ‘God’ Ibn ʿArabī means the ultimate spiritual experience with whatever is there. He doesn’t want to personalise God. He remains in this fluctuation between the sense of the ego, and the sense of the infinite which is mysteriously approachable. The issues which he raises are really open questions. That’s why people have read the works of mystics for centuries. If you have a proposition like 2+2=4, the issue is clear: you don’t have to spend a lifetime thinking about it. But when you come to these deeper mysteries, it’s a search.

The analogy of the waves and the tide is really a beautiful image for spirituality. What makes the tide stop? Why doesn’t it keep going and swallow up all the land? It barely touches its maximum, and then it shoots back from the shore. In the same way, we come close to understanding the beauty of a flower, but then it escapes us – the tide recedes. Water is the closest thing to our minds. We touch it and it’s not there; we hold it and it runs away. That is why ocean images are so pre-eminent in spiritual literature.

Jane: One of Ibn ‘Arabī’s most famous quotes is: “The self – or soul – is an ocean without a shore”. How does that fit into this analogy?

Etel: It’s without a shore in the sense that we say that the wave reaches the shore, but in fact, it doesn’t. It has its own momentum when it hits the point where it comes back. The boundaries are not ‘hard shell boundaries’, but they represent the extreme point of the possibility, the creation of its own limits.

There is always a greater possibility for us, and this is at the same time both infinite and limited in its nature. Otherwise we will simply faint in total annihilation, fanāʾ; we will be dissolved and no longer be here. We have to keep the idea of the existence of the self, because if we lose that we are not here, we don’t exist. The beginning of thinking is the beginning of possibilities, where the self is created by God, but is also autonomous. Like your hand is autonomous but it’s also part of your body, and your body is part of the world; it has boundaries, it has its shape, but it is still part of the world. You can’t get it out of it.

People have to understand that a writer like Ibn ʿArabī does not bring knowledge in a ‘hard shell’ way. He is a practice. We read him and it lights our imagination. We don’t learn 4+5=9; it’s not that type of a definite step that we take forever. It is an expiration, which pushes us back to ourselves. So to read Ibn ʿArabī is to receive or create a spiritual event. With every reading, he invites us to approach what he calls God, and he brings us back to the self.

David: You have said: “We are not looking for a great apotheosis, let’s have a conversation and a cup of coffee, because this is how we come together.”

Etel: Conversation is the beginning of civilisation. It’s the most important moment between people, where we have that link together. Spiritual life is not to do with having a big epiphany. Some people are waiting for that apotheotic moment, which could be the moment of one’s death. But we don’t live all the time in a ‘boom!’ like the atomic bomb. But we do have these little precious moments.

It was through reading Ibn ʿArabī that I realised that I am not religious in an ordinary way. Christianity and Islam are part of our cultures, they affect the world, but I feel that we each need to find our own approach to these things. This could be pure thinking, like reading Ibn ʿArabī, but it can also be practice, and not necessarily of art. For instance, an astronomer comes very close to the idea of the Absolute by being so much focused on the universe, and even an artisan shoemaker can come close to moments of profundity.

I don’t like the elitist approach that thinks that mystics and artists are superior. They are not. They have their ways, and these are sometimes so beautiful that we admire them. But someone thinking privately is just as important. Bankers may have their own epiphany, through their work or outside it; we don’t know what happens. Let’s admit that every being, including animals, has profound expressions that we do not have. I am sure they do. You see an animal living – an elephant, a cat – and tremendous things are happening there! I wish we could be more democratic in our ways of thinking.

Series of Mount Tamalpais watercolours displayed at the exhibition ‘Etel Adnan: une grande figure des arts’, Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris, October 2016–January 2017. Courtesy of IdMA

Jane: It seems that one of the great themes in your work is love – love of people and love for the world. When you were invited by Kassel to contribute to their famous essay series, you chose the title: ‘On Love and the Cost We are not Willing to Pay Today’.

Etel: Love is not easy. Love of another person is the hardest thing to manage, and I think the most interesting. But there isn’t only love for a person; there is love for your everyday things. I love nature above all. It attracts me more often than art, and I would rather see a river than a museum. I yearn for that. California does that to me; it’s so beautiful, you feel as though you are in paradise, because it exalts you physically all the time.

I speak about the mountain in the same way that Ibn ʿArabī talks about what he calls God. For me, it became a being in its own right. I have painted it and drawn it many times, but the painting and drawing is never done. This is also true of cooking; the cake is never the same. Every experience is unique. And it is also true between people. Being is never totally there, and relationship is mysterious, and love is not finished, ever. What we call love is a relationship that never ends; it is like a wave that keeps bringing you back to it, so we are like surfers who are always running after the perfect experience. It is the same with mystical experience. What we call beauty is a form of it – something that stops us and empties our minds. It’s a power of the mind, which even children have; a power of the mind to free the self and face something in a pure state.

David: Would you say that it is this which lies behind your creativity?

Etel: I suppose it is. There is searching for something, but we don’t know what we search for. If we knew what we were searching for, we would in a way have already found it. What we are talking about is an inner drive, almost a physical energy – a kinetic drive that pushes us forwards. It is perhaps like little animals who immediately leave their mothers: to go away from the starting point is the movement of life. It is this same kinetic movement that pushed Ibn ʿArabī as far as he could go, and pushes each one of us as far as we can go. We are on a perpetual voyage. To be alive is to voyage, to travel, and that applies to everything, including animals and plants.

Etel Adnan: The Weight of the World, Serpentine Sackler Gallery, London (2 June–11 September 2016). Image © Tristan Fewings/Getty

Image Sources

Banner: Etel Adnan in her flat in Paris in 2016. Photograph: Laurene Mercier [/].

First inset: Etel Adnan: Theh Weight of the World.

Email this page to a friend

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE