News & Views

Sacred Number

and Its ‘Incarnation’ through Geometry

Tom Bree responds to the article

‘Calligraphy – A Sacred Tradition’ in Issue 11

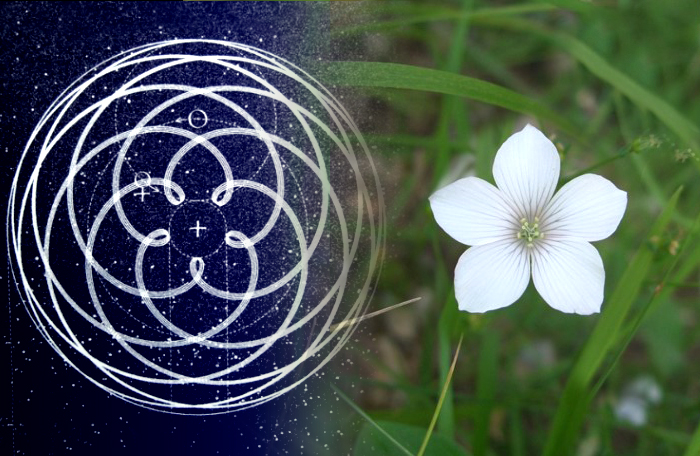

‘As above, so below.’ The form of the pentagram as shown by the celestial movement of Venus and petals of the wood sorrel flower

In the modern world the focus upon number, structure and more generally ‘order’ is often associated with a rational scientific outlook. This perception can lead to an opposing reaction in which the casting away of such ‘oppressive’ fixed boundaries is seen as a glorious escape from an entrapment within detached analytical thought processes that somehow disregard spirituality, intuition, emotion and more generally a direct experience of things that can bypass the analytical mind. The rationalist outlook claims a superiority due to its capacity to view the world with a detached objectivity, whereas the experiential approach claims superiority due to its direct ‘tasting’ and thus knowing of things.

This dichotomy is an unfortunate phenomenon of the modern world, creating a division between these two modes of perception despite the fact that as humans we have the capacity for both. By seeing the two modes of perception as being irreconcilable, we end up condemning ourselves to a state of inward divorce and division.

The Practice of Geometry

.

As a geometer-artist, teacher and researcher, I deal with the use of geometry as both an art form as well as a contemplative philosophical focus. The practice of geometric art requires a certain amount of technical capacity involving logical thought processes, although in a more overarching way than in science. The whole process of pattern making is a contemplative one in which the soul is encouraged to orientate its vision towards the boundless, albeit through the bounded numerical forms of geometry. In the drawing of a pattern, the soul presents itself with a visible reminder of the order, harmony and beauty that it ultimately is, regardless of the hardships and disorder that often pervade our day-to-day earthly existence. In this sense the practice of geometric pattern making uses the visible forms of this world to point towards something that is ultimately beyond what can be seen.

The difference between idolatry and iconolatry is in the relationship that we have with the icon/idol that we see in front of us. If we only see the visible form of the object, it is an idol in the sense that we are materialistically only seeing its outward appearance. But if the object is, symbolically speaking, ‘transparent’ then we can see through it, as it were, towards an eternal reality that lies beyond it. In this sense, the bounded world in which we live is only an entrapment if we reside purely in materialistic ‘measurable’ perceptions rather than seeing the measureless through the measurable, the heavenly through the earthly, the One through the many, or, geometrically speaking, the hidden centre of the circle through its visible circumference.

The World as Beauty

.

The whole cosmos could be looked upon as a theophany – a divine appearance of the eternal numerical thoughts of the Divine Mind. Cosmology in the ancient and medieval worlds required a very developed technical and mathematical know-how, although its primary purpose was to contemplate the divine reality. The Greek word cosmos literally means ‘order’, because the movements of the heavenly vault above us follow numerical cycles. However, the word cosmos also relates to Beauty in the sense of a beautiful ‘external adornment’ through which the hidden can become revealed.

This association of beauty with order was an essential aspect of ancient and medieval thought but the Beauty in question is ultimately beyond anything that the human eye has the capacity to see. So in this sense, the cosmic movements overhead are merely an image of the eternal and unchanging realities of number that are forever known in the Divine Mind. To contemplate such numbers and use them in sacred art and architecture is thus to align the soul, along with its surroundings, with the knowledge of the Divine Mind.

But having said all of this, the Divine Mind itself is like the hub of a clock in that it lies at the root of the ordered movements of time but is ultimately beyond them, located as it is in the central unmoving realm of the timeless…and so it is that “Time is a moving image of eternity”.

Image Sources (click to open)

The Venus Pentagram as drawn by John Martineau in The Little Book of Coincidence in the Universe (Wooden Books, 2002).

The wood sorrel flower photographed by Tom Bree.

For more on the geometry of flowers, see Keith Critchlow, The Hidden Geometry of Flowers (Floris Books, 2011).

Tom Bree teaches practical geometry art classes about the use of geometry in sacred art and philosophy. He teaches at the Prince’s School of Traditional Arts in London, the RWA in Bristol and the Chalice Well in Glastonbury as well as for various other organisations and institutions.

Tom has been researching the geometric and cosmological design of Wells Cathedral in Somerset for eight years now and is currently writing a book about his findings. The working title of the book is The Cosmos in Stone. As part of this research Tom has taken a close interest in the cosmological phenomenon known as the Venus Pentagram cycle. See the YouTube video below in which the phenomenon is demonstrated by Tom himself with the help of some of his students.

More News & Views

Poems for These Times: 18 – New Year 2024

Benjamin Zepahniah | Faceless

“You have to look beyond the face

to see the person true

Down within my inner space

I am the same as you…”

Introducing… ‘Tiger Work’ by Ben Okri

Barbara Vellacott reads from and discusses a new book of stories, parables and poems about climate change

Book Review: “Elixir: In the Valley at the End of Time” by Kapka Kassabova

Charlotte Maberly reviews a book about the search for wholeness, and a heartfelt plea to reclaim our spiritual, physical and emotional unity with nature

Book Review: “Work: A Deep History” by James Suzman

Richard Gault reviews a new book which takes a radical approach to contemporary work culture

Introducing… Bernardo Kastrup and Swami Sarvapriyananda

Charlotte Maberly appreciates a wide-ranging video conversation about Eastern and Western concepts of the self and mind

Connecting Threads on the River Tweed

Charlotte Maberly investigates an innovative project which explores cultural engagement as the driver of ecological change

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READERS’ COMMENTS

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

0 Comments