Finance & Global Affairs _|_ Issue 2, 2016

The Ecology of Money

An interview with Ciaran Mundy, director of the Bristol Pound

The Ecology of Money

An interview with Ciaran Mundy, director of the Bristol Pound

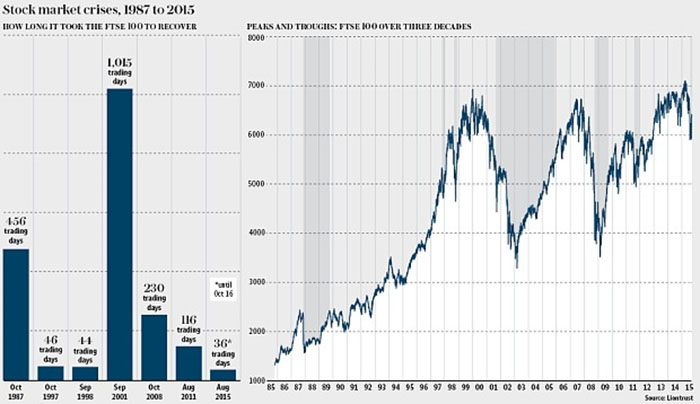

When the Beshara Magazine started in 1986, the world was just at the start of the process that we call ‘globalisation’, and we were witness to the initial stirrings of a financial hurricane that was set to rise up and swirl its way through our economic systems, clearing away the structures of the past. The events that followed have given credence to the unstable nature of modern finance: the first high tech ‘bubble’ expanded and crashed in 2000 before growing again in a more measured way; then, released from traditional boundaries, money, banks and markets spiralled out of control and resulted in a near collapse of the whole global financial system in 2008. If we needed any reminder that the financial world is a single entity in which – to borrow a concept from chaos science – ‘the flap of a butterfly’s wing’, in the form of, say, a mortgage in Minnesota, can result in storms all around the globe, this provided it. Since that time, governments, banks, businesses and individuals have been trying to work out the way forward towards a state of steady growth and prosperity. But they have had only mixed success; the ‘rules of the game’ have changed and nobody really understands everything that is going on.

When the Beshara Magazine started in 1986, the world was just at the start of the process that we call ‘globalisation’, and we were witness to the initial stirrings of a financial hurricane that was set to rise up and swirl its way through our economic systems, clearing away the structures of the past. The events that followed have given credence to the unstable nature of modern finance: the first high tech ‘bubble’ expanded and crashed in 2000 before growing again in a more measured way; then, released from traditional boundaries, money, banks and markets spiralled out of control and resulted in a near collapse of the whole global financial system in 2008. If we needed any reminder that the financial world is a single entity in which – to borrow a concept from chaos science – ‘the flap of a butterfly’s wing’, in the form of, say, a mortgage in Minnesota, can result in storms all around the globe, this provided it. Since that time, governments, banks, businesses and individuals have been trying to work out the way forward towards a state of steady growth and prosperity. But they have had only mixed success; the ‘rules of the game’ have changed and nobody really understands everything that is going on.

Returning to the discussion after twenty-five years, it seems that it is not enough now for the Magazine to simply point out that the instantaneous response throughout the financial world to events such as the recent vote for Brexit in the UK, or the global jostling in the South China Sea is a manifest sign of our global interdependence. We need to dig deeper. We can see the froth on the waves, but what is going on beneath the surface?

Delving into the depths means asking questions about fundamental concepts. What is money? Is it the same as wealth? What are the assumptions about values and the aims of human life that underpin our economic models? How can we create an economics which is less damaging to nature and the environment? Fortunately, we are not alone in beginning to ask about these things: many people from a wide range of disciplines – not only economists or bankers – are entering the conversation. In just the last few weeks we have found the anthropologist David Graeber exploring the history of debt in the Radio 4 series ‘Promises, Promises’ [/], and the physicist Stephen Hawking in The Guardian urging us to rethink our understanding of wealth [/].

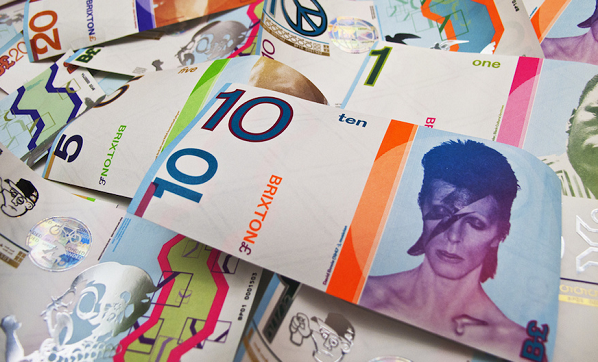

There are also a host of new initiatives that are experimenting with alternative economic models on the ground. Amongst these are a number of local currency projects which have set up alternative money exchanges in places such as Totnes, Brixton, Bristol and Exeter, as well as in continental Europe and further afield. Of these, the Bristol Pound [/] has perhaps the highest profile: founded in 2012, it has achieved a level of participation, and hence turn-over, beyond any previous expectations. So in the first of what the Beshara Magazine intends to be a series of articles exploring new economic ideas, we travelled down to Bristol to ask its director, Ciaran Mundy, what insights such experiments can give us into the workings of contemporary finance.

Economics is the Ecology of Money

.

We began by asking Ciaran how he came to set up the Bristol Pound project. “I ran my own businesses for many years, including IT support, property and a small mobile phone distribution company. But my academic training was as a soil ecologist, so alongside my business life I set up a charity with a business partner, and for many years we worked on wildlife projects, educating people about the importance of ecosystems and habitats. Working in both these lines of work simultaneously, again and again I could see that there are broad economic systemic reasons why we have problems with collapsing ecosystems and the mass extinction of other species – problems related to what is known as the ‘anthropocene’, meaning the era where humans as a species are having geological scale impacts on the whole planet and its living systems.”

Then one day, it occurred to him that the money system is a set of rules that determine how resources are shared around the global economy, and that means that it can be understood as a kind of ecosystem. “I saw that economics is the ecology of money. Money is a social construct: it is not a thing in itself but each bit of money is a contract of a certain size that allows us to make a call on wealth. I began to see how the individuals operating within an economy are like the species within an ecosystem, and that the way the different actors relate to each other, and the way that resources are allocated, is very much determined by the way that money works.”

This led him to think about an ecological economics, and how monetary and financial systems could start to take account of the fact that we are all part of a living world and not separate from it. As a consequence, he became involved in a range of projects in Bristol and met people, particularly his colleague Chris Sunderland, who wanted to establish a local currency project.

“Money is essentially created based on our common trust”

Since its launch the Bristol Pound has become the largest local currency in the UK, having issued about £2.5 million in the local currency in the last four years, and involving 850 businesses and 1,400 account holders. It is the first local currency at this scale to have utilised digital media to the full, so that people can use online accounts and pay using Smart phones. Citizens and businesses of Bristol can use Bristol Pounds to pay local taxes and business rates; the City Council partly pays its employees in them. And the scheme continues to extend its scope: a recent development is the inclusion of a locally-based green energy supplier and the ability to pay for most local transport links, including any train journey out of the main station in central Bristol.

The Story of Money

.

Nevertheless, as Ciaran points out, in financial terms it is still a drop in the ocean. “The size of the Bristol economy is about £12 billion, and even if you don’t take into account some of the big businesses that we do not get involved with – such as BEA who build weapons systems and aircraft – it is still in the billions. Similarly, there are some 40,000 businesses in the region, and we have got about 850 businesses using the Bristol Pound.”

For him, the really significant contribution of a local currency is that it educates its participants in the nature of economics. “What the Bristol Pound does really well is tell a story about money. People don’t really know what money is and through participating in a scheme like this, they start to realise that they don’t know. I didn’t know myself until I started this project. Then I began working it out bit by bit.”

So what are his conclusions? “Well, money is essentially created based on our common trust. It can be created in different ways, but what you end up with is something that people agree is a trustworthy contract, whether it is on a piece of paper, or a digital contract, or stamped on a piece of metal. It is an exchangeable contract that everybody understands, and which can be swapped in exchange for goods or services. It is an IOU basically.”

The aspect which engages us here is the centrality of trust, and we ask Ciaran to explain further: “It is important to understand how we manage debit and credit. If I give you a credit, I either have goods, or I have time, and I will work for you and I will do this job that you want me to do. For instance, a local carpenter will say: ‘I will build your kitchen and you don’t have to pay me until it is done.’ At that moment he is effectively issuing credit to you, and all along the way you are building up a debt with him. This is to all intents and purposes the same as running a loan book – and this implies trust.”

This leads on to a further question: how is money created? “In practical terms, the way it works in our current system is that banks create money out of nothing, based on the fact that there is a contract between the bank and an individual or a business. The contract will say ‘If we give you money, say £100,000, to purchase a house, then you will promise to keep paying the bank back until the debt is paid, including the interest, which may bring the total to £200,000.’ That very contract is the basis on which the money is created: there is nothing else, no other thing anywhere, necessary. The bank then has a call on that person’s labour to keep working so as to pay them the money that they get from working for other people.”

This is not the way that most of us think about money. We assume that it corresponds in some way to the level of our collective wealth. But Ciaran’s explanation is completely in line with the current understanding of economists and bankers. As a recent article published by the Bank of England, ‘Money Creation in the Modern Economy’ [/], points out:

[A] common misconception is that banks simply act as intermediaries, lending out the deposits that savers place with them. In this view, deposits are typically ‘created’ by the saving decision of households and banks then ‘lend out’ those existing deposits to borrowers…

[But] in fact… saving does not by itself increase the deposits or ‘funds available’ for banks to lend. Viewing banks simply as intermediaries ignores the fact that in reality, in the modern economy, commercial banks are the creators of deposit money… The act of lending creates deposits – the reverse of the sequence described in text books.

Such a scenario clarifies the extent to which the entire global financial system is completely dependent on trust between participants. If that is undermined, such as it was in 2008, everything starts to collapse. It also brings us to a question about the relationship between money and wealth, and we ask Ciaran: are these the same thing?

“No. Wealth is when you take raw materials from the environment, or time and energy that people put into work, and you say, ‘Given that I have the ability to create and manipulate these raw materials, I have changed the world around me in some way.’ This change that I have brought to the world is wealth, whether it is the crop that a farmer grows as opposed to leaving the land as forest, or timber that is taken from the forest. The change is the human interaction with the natural world that creates something that another person agrees has value. It is this value that we call wealth.”

So what is the role of money? “Money is a call on wealth. What financial institutions do is create the money which controls wealth, and at the moment 97% of it is created as a debt contract between a bank and an individual or business. And it is a contract in which people not only have to pay back all the money that has been created for them but also they have to pay interest. And this means that there is either an imperative for growth at all costs, because there is always a greater amount to pay back than there was in the first place due to the added interest; or there is an imperative for inflation, so the value of money is constantly degrading and what is paid back is worth less in the future. In this way you have a need for inflation or growth built into the economy. Both of these mean that the situation is unsustainable in the long run, resulting in an inherent tendency towards collapse. And, of course, a lot of the time there is also the impoverishment of the people who are having to pay back the interest charged by the bank.”

“Money is a call on wealth”

Community and Identity

.

Is a local currency, then, just a kind of ‘thought experiment’ to learn about the nature of money, or are there tangible economic benefits? Ciaran explains that although the Bristol Pound is essentially a voluntary scheme which runs alongside Pound Sterling, it can bring about real change at the level of community: “At the moment, money quickly travels through some long supply chain and very often ends up in an off-shore account. The last serious estimate of the global amount of money sitting in off-shore accounts was done by the Tax Justice Network in 2015 who found that it totals somewhere between $21 and $32 trillion. That is a huge proportion of the global ‘call‘ on wealth, a significant portion of the money that exists.”

Indeed it is – exceeding the annual GDP of the USA, which is about $18 trillion. The existence of these accounts, explains Ciaran, means that the money that people are creating is constantly being drained out of the economy and is therefore not available to help them create further wealth. “What a local currency can do is put some barrier up to prevent that, and say, ‘Before you are going to spend it at some international company that uses offshore systems – whether it is Amazon or Starbucks – think about buying locally. Allow it to build up, rotate and circulate locally rather than just passing straight through the system.’ If we can have a diversity of traders, more of that money gets re-circulated.” He points out that about 80% of the Bristol Pounds issued will recirculate locally: “whereas if you spend money in one of the large supermarkets, about 80% of it will leave the city in quite a short space of time. So there is a big difference. It means that over time, the economy is steered in a very different direction, allowing a much more sustainable and equitable system.”

This can have a real effect on local economic conditions. Research shows that pound for pound, local businesses create more jobs than multi-national companies; they pay better wages and the pay differential between owners and employees is much less than in large organisations. Signing up to the Bristol Pound also means that businesses do more sourcing locally, and this has a significant impact on the environment because of reduced emissions from transport and less emissions from poorly regulated manufacturing overseas.

Local currencies also counteract the phenomenon of what the New Economics Foundation has called “clone-town Britain” [/] – a term coined to describe the increasing dominance of chain stores and global franchises on the high street and the closing of small local enterprises and shops. In its 2004 survey of over a hundred towns and villages across the UK, the NEF identified that over half of them could either be classed as clone-towns, or were on the brink of becoming so. For Ciaran, creating a sense of community identity is a very important role for local currencies. “People have a greater sense of agency, I hope, as a consequence of Bristol having its own money. People get excited about it. At a very intuitive level it is quite empowering. Loss of diversity is a real danger for communities. Places where you do not have a lot of local ownership of businesses tend not to be happy places.”

Fragility and Resilience

.

Discussion of diversity leads us back to the ecological metaphor, and the ways in which complex inter-connected systems like the world economy can achieve stability and what is technically called ‘resilience’. Ciaran sounds a note of caution about expecting too much of projects like the Bristol Pound. “On their own, they cannot provide an instant solution in the case of a ‘collapse’ scenario, because the structure of the economy is very globalised. But it is a beginning. From an ecological point of view, resilience is the ability of an ecosystem to carry on in the face of environmental change, with the various interacting entities within it continuing to survive. That happens in economies all the time. Resilience is based ultimately on the ability of the entities within a system to be dynamic and to shift and change their relationships.

“The problem we have is that the more efficient a system becomes – financial efficiency being a very good example – the more fragile and brittle it becomes because there is no room to stand back and think ‘what could I do differently?’ When a financial system is operating very efficiently, so that everything is as cheap as it can be, and everybody is working to the nth degree to pay off their mortgages, they don’t have time to consider other options. This is not a very good place for society to be.”

Here again a local currency can act as a buffer against global forces: “Under the current globalised system, peoples’ security can just be snatched away – their jobs can be moved overseas because of some change in the tax system and they can be left with nothing. If you live in a city like Bristol where there are a lot of supportive networks, then you can fall back on those communities and say, ‘Now I have some time on my hands, can you use me?’ We are not all dependent on the same system, because it is an economically diverse city, and there is the capacity to pick up people who would maybe fall out of a much more rigid system.”

Nevertheless, Ciaran is not happy to make an over-simplistic use of the ecological analogy: “If you look at natural systems, you do get monocultures to some degree or you get a very dominating species, for example social insects like driver ants. They build up their numbers, and take a lot from their surrounding system. Then, when they have eaten all the other insects or driven them out, their numbers start to collapse, so they have to retrench and move on somewhere else. Capitalism can sometimes be like this. But once you are operating a global financial system, once you have used up everything, where do you go?”

Alternative Models

.

Having established itself over the last four years as a feasible project, the Bristol Pound is now planning to enter into new areas of experimentation. One proposal is that it should start making its own loans. “We have provided a tool – an instrument – that other people can use”, explains Ciaran. “With time this could operate as a systemic intervention, and we hope fairly soon to get to a point where we can start issuing the currency as credit to solid businesses.” The important difference is that no interest would be charged on the loan itself. Instead, transaction fees would be charged to cover the cost of running the system. We ask him about the WIR Bank in Switzerland, which was founded in the aftermath of the Great Depression in 1934; it issues its own money, the WIR Franc, and turns over as much as two billion CHF a year, charging either zero or very low interest on its loans. Does this provide an exemplar? “Yes, the WIR is a much bigger system, a national system. People use it as an alternative system for business as things wax and wane in the use of the Swiss franc, and businesses can switch to the WIR during economic downturns.”

Another initiative, already under way, is the establishment of a network of alternative projects around the UK: “If we stay connected as a network of collaboration, that is a much more resilient way to approach the development of new models in the face of a very, very big challenge.” Ciaran is clear that the aim is not to replace our current economic system: “I think that the mainstream economy does a lot of damage to communities and the environment. But it also achieves a lot for people, and it generally works. So there have not been serious challenges to it in the last 25 years. There are lots of alternative schemes, but at the moment they are so small that the momentum will probably remain with charging forward with global financial capitalism. But, as we have said, there is an inherent collapse built into that system. So we need other models ready to go.”

“We should be building systems to make sure that human values are carried right through the global economy”

One of the major challenges is how to incorporate larger companies. At the moment, the Bristol Pound does not allow companies listed on the stock exchange to participate because there is no clear way to deal with the issue of shareholders. “It is a very complicated world, and I don’t want to pretend that we can always come up with simple solutions. We retreat from the complexity of the world very easily, but then, if we are not careful, we cede that territory to people who have a different set of priorities and perhaps don’t even care about what we might call ‘human values’. We should not refuse to engage with the world of complex finance, but rather, we should be building systems that work to make sure that human values are carried right through the global economy.”

Economics and Human Values

.

This leads us, finally, into the question of values, and the assumptions about human nature that underpin our current economic system. Ciaran refers us here to the work of Tom Crompton of the Common Cause Foundation [/]. Their research indicates that most human beings around the world care about their families, their communities, and being able to make a contribution to the society that nurtured and supported them. “A sense of connection with the natural world and with each other are the most important things for people wherever you go. Of course, they are not the only human values: we also value having power, being seen as clever or beautiful and, having these more extrinsic goals, we then seek success and access to wealth. We all hold all of these in our minds and in our hearts. It is just that some of these values are given much more emphasis by the modern economy than others.”

Crompton makes a distinction between what he calls ‘intrinsic values’ – those with a sense of connection to nature, to community, wanting to do things for their own intrinsic worth – and ‘extrinsic values’ which are to do with the pursuit of an external goal such as getting rich or being sexy. Ciaran points out: “There is a misconception, which is promulgated throughout the world, that what matters most is being competitive and achieving external goals. The evidence is that most people are not primarily motivated by those things, but they think that other people are. So people are quiet about the other things, and think, ‘If only other people cared about what I care about, then I would feel free to be like that myself’.”

It is these ‘intrinsic’ values of community, inter-connectedness and service that lie at the heart of the local currency project. As Ciaran puts it: “It is not just all about getting richer. In fact, these kinds of projects will not make us rich. But they might connect us more to our local community. They might build stronger relations between us and our customers in a way that we find enriching at a more meaningful level. We are saying to people: ‘What do you really care about? Drill down to what really matters to you, and we will be there to support those things.’ This, then, is another form of real wealth, that wealth of connection we have for each other in our community. It matters way, way more to all of us than we often realise.”

Image Sources (click to open)

Our thanks to the Bristol Pound; Christy Nunns; and Marks Simmons of bristolgreencapital.org for the images used in this article.

Other Sources (click to open)

“Promises, Promises: A History of Debt” was broadcast on BBC Radio 4 as two Ominibus editions on 29 July and 5 August 2016 (see http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b054zdp6). This brought together the episodes previously broadcast in 2015.

STEPHEN HAWKING’s article “Our attitude towards wealth played a crucial role in Brexit. We need a rethink” was published in The Guardian on 29 July 2016.

Quote from “Money Creation in the Modern Economy” by MICHAEL LEAY, AMAR RADIA and RYLAND THOMAS of the Bank of England’s Monetary Analysis Directorate, Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin 2014, Q1, p. 2.

The New Economics Foundation report “Clone-Town Britain” is available as a PDF on http://b.3cdn.net/nefoundation/1733ceec8041a9de5e_ubm6b6t6i.pdf

Email this page to a friend

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

READERS’ COMMENTS

0 Comments