A Thing of Beauty _|_ Issue 9, 2018

A THING OF BEAUTY…

Mark Boston reflects on painting the film Loving Vincent

A THING OF BEAUTY

Mark Boston reflects on painting the film Loving Vincent

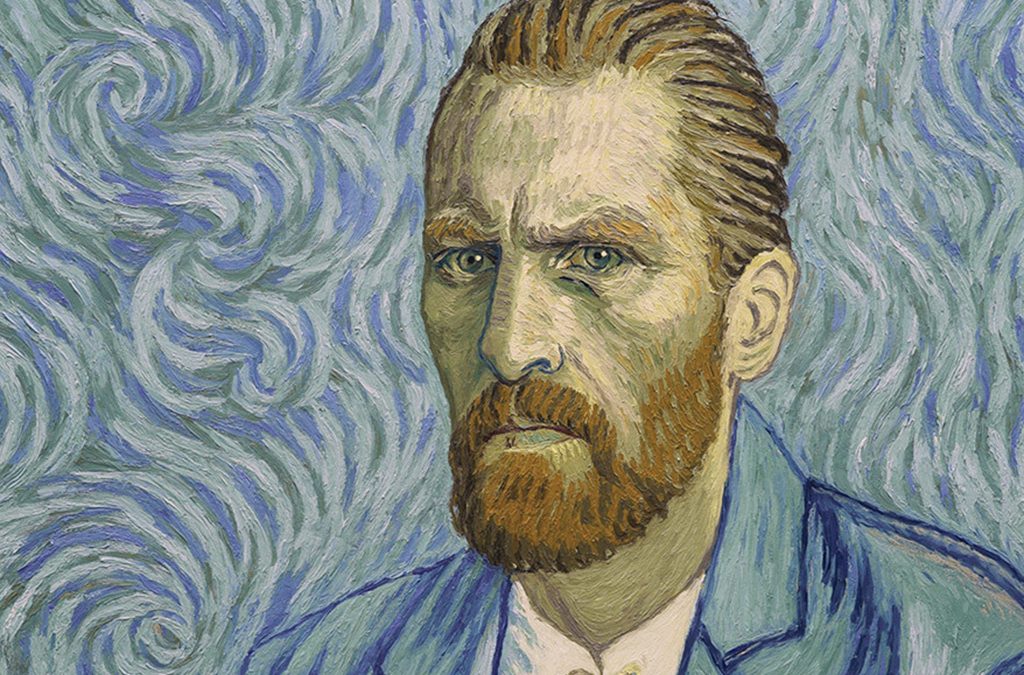

‘Loving Vincent’ is an animated film which investigates the tragic and mysterious death of one of the world’s most celebrated painters, Vincent van Gogh. Its unique feature is that it was painted by hand in van Gogh’s own style, based upon his portraits of the ordinary people – barmaids, postmen, doctors – he met during his life, particularly during his last days in Auvers-sur-Oise, near Paris, and the landscapes he captured in glorious colour on canvas. Conceived by the Polish director Dorota Kobliela, the film was created over a two-year period in Gdansk, and turned out to be an extraordinary work of art in its own right. Amongst the team of young painters who helped to create it was Mark Boston, an animator and artist, who here reflects upon his experience.

“We are surrounded by poetry on all sides, but putting it on paper is, alas, not as readily done as looking at it” (Vincent van Gogh, March 1883).

In a small, paint-stained workspace hidden behind dark curtains, I sit and contemplate the strange task given to me.

To my left, an array of brushes and a careful selection of paint pots; to my right, the computer keyboard and a control for the camera which hangs from the ceiling. Beside the camera sits a projector, casting down a mysterious light. Above, connecting the camera and the projector, the computer monitor displays various images for reference, including rough video footage, photos of van Gogh’s paintings to study the technique and colour, and the live image the camera picks up. Then, directly in front of me, the focal point of this curious little room – the canvas board that will host the magic.

And I wonder: who was this man, Vincent van Gogh?

As I walk from the Polish summer into the darkened corridors, it is impossible not to feel the presence of this legendary Dutch painter, whose resilient spirit is infused into every stroke of paint that hits canvas here. But this is no art gallery or history class. Instead, I find myself in an inconspicuous warehouse, not far out of the centre of Gdansk, where something astonishing is quietly under way. A thing of beauty, slowly emerging from hours of work, gradually comes to fruition. Loving Vincent ‘the world’s first fully hand-painted feature film’.

The painters’ booths in the studio in Gdansk

Painting the Film

.

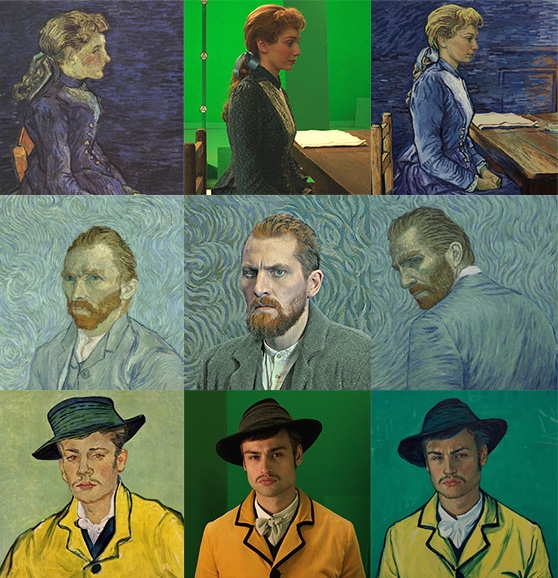

Almost a decade has passed since Dorota Kobiela, co-director and creator of the project, began the painting for an experimental short film, inspired by the manifold letters van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo. With the support of a Kickstarter campaign in 2012, along with production company Breakthru Films and The Polish Film Institute, funding and enthusiasm propelled the project into a feature-length endeavour, bringing together a team of film-makers, actors and artists to imaginatively explore van Gogh’s vision, and the circumstances surrounding his unexpected death in the year 1890. This combined support established a space to record live-action performances, reflecting the people van Gogh painted, and to set up three painting studios, where a team of 125 painters would render this recorded footage by hand in oil paint.

I am welcomed as one of the final painters to join this strange and wonderful process in the last few months of production. Once introduced to the technique, and after a week and a half of intensive training, I feel familiar enough with van Gogh’s brushwork to begin the first painting, which will provide the basis of a five-second-long shot mid-way through the film. The task is not immediately daunting, having emerged from the animation studio at Edinburgh College of Art a month earlier. There, I had been experimenting with paint on glass animation, and had first felt the thrill of making painted images ‘come alive’. Now, immersed in an intensive, professional environment, there is no time for play or experimentation. The perfection of each brushstroke is essential to the finished 90-minute film, and suddenly the challenge becomes very clear.

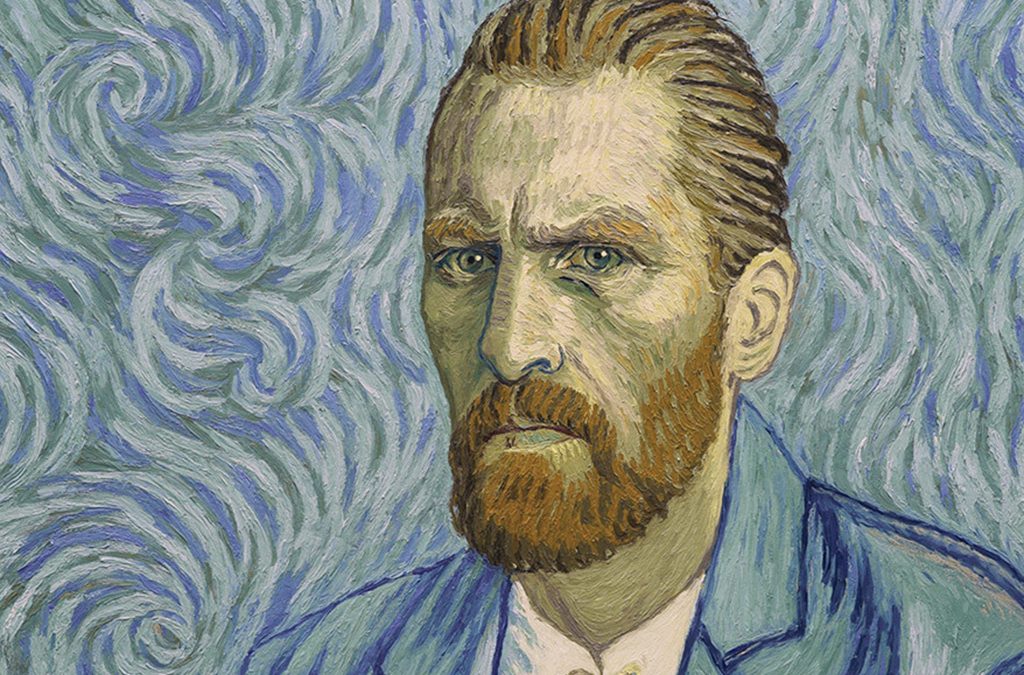

Still from the film. Armand Roulin, son of the postman, played by Douglas Booth [/], with the Boatman, played by Aidan Turner [/]. Painting by Iga Oliwak

Each second of animated film demands 12 images, or ‘frames’, to create and maintain the illusion of movement for the human eye. Thus, every second of the live-action video recording is separated into 12 individual frames, which provide the basis for the finished paintings. I sit and closely inspect the 60 rudimentary images, which together form a shot of the protagonist Armand in mid-argument. The background stays the same, but the character’s expression is constantly shifting, meaning the entire face must be wiped clean and repainted each time. To understand the full movement is important, as is the awareness of already-completed neighbouring shots to achieve consistency in colour and texture. Referencing the original van Gogh paintings associated with the scene is also necessary. After mixing the paints and testing the colours with the camera, it takes a few hours to complete the first frame. When approved and photographed, this provides the basis for the following 59, which are painted on top in succession.

Altogether, approximately 65,000 paintings are necessary to make the film – a task that would take one person 81 years to complete! But working alongside 125 painters is not merely an advantage. It is an education, and a celebration. An education because preconceived methods and techniques are put aside in order to align with something new – in this case, the style necessary to make the film harmonious. Something different and fresh is drawn out in the letting go of what is already known, for each and every painter. And it is a celebration because of the rare opportunity for togetherness: the chance to co-create and to share a work of art. It is an unexpected joy to wield a brush in the company of others, and to transcend the solitary life of the conventional painter. For many of us, this is the first time we are working together in creative collaboration, with a shared vision and focus, on a project that has the love of painting as a fundamental element.

The support of co-painters, all partaking in what seems like the endless repainting of an image, is hugely important. The demand to remove the paint once completed and photographed is often difficult to accept. The nature of the process – painting one image to perfection then wiping the board clean for the next frame – even coming to it as an animator, seems a clear road to madness. The fruit of the labour is seen only afterwards once several paintings have been photographed and are played in sequence. But the intensive absurdity of the situation leads me to important questions.

Later, when frustrated and disheartened by the task, I ask myself: what was it that had drawn me, some nine years ago, to pick up a brush and begin painting? What was it that attracted me, a few years later, to the somewhat absurd practice of animation? What is it – between that flash of inspiration and the emergence of a created artwork – that fuels and ‘animates’ the artist to carry out the task given by the indwelling creative spirit?

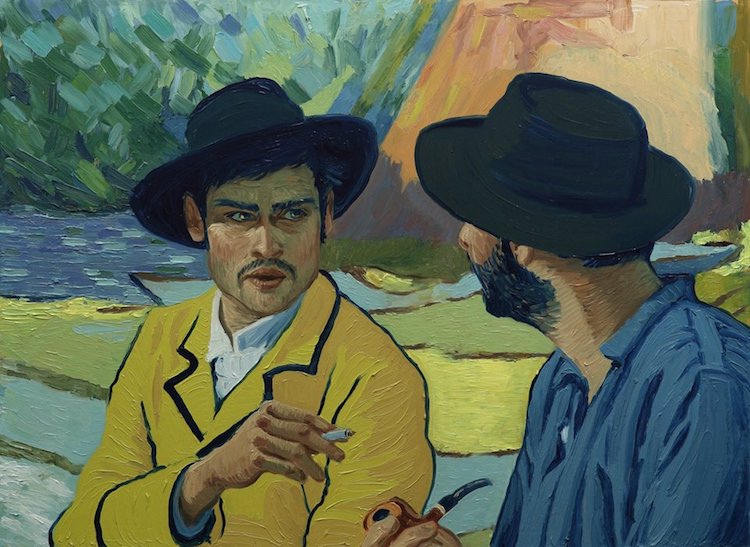

The transformation of the original paintings. Left, the original painting; middle, the actor in costume; right, a still from the film. Vincent van Gogh and Armand Roulin as above, plus Adeline Ravoux, of the Auberge Ravoux where van Gogh died in July 1890, played by Eleanor Tomlinson [/]

The nature of animation requires each image, however beautiful and perfect, to be sacrificed for the sake of the finished film: to gaze or focus too much on one image is to miss the purpose. Yet, paradoxically, each painting in Loving Vincent needs the utmost care and attention, and becomes, inevitably, beautiful in itself. To rush a painting would be detrimental to its scene, breaking the fluidity and rhythm of its imagery. Each frame is important for the harmony. A single frame that has been given less attention or painted hurriedly resembles a missed note in music, yet it is in the ‘letting go’ of each note that the symphony is heard, its beauty felt.

Considering this mystery, I escape the tedium and deepen into the calm, focused quietude necessary for the task. As I paint the same face over and over again, my awareness shifts between two states, each with its own discipline. Forgetting for a moment about the multitude, I return my focus to one painting for itself. Here, each stroke of paint is a new breath, an anchor to the presence of artist/artwork, and what emerges is timeless. Then my awareness shifts to the multitude and the dimension of time becomes an integral part of the artwork. Each finished painting becomes like one of its own ephemeral brushstrokes, alive and expressive with its own beauty for a split second, then wiped away, transformed in the blink of an eye: the timeless ‘now’ in relationship with time, in order to move, to live, to unfold; the solitary image now part of a grand dance, the beautiful continually re-emerging.

In the end, everyone involved must disappear from view for the sake of the film, which moves seemingly by itself on the screen. It comes alive only when the creator is out of the way, hidden. Likewise, the world knows van Gogh through his paintings, while van Gogh himself remains hidden behind them. But the hidden is not separate from the manifest, and the artist is inseparable from the work of art. There comes a point in any artistic practice where this becomes experiential, and necessary for something fuller, more genuine, to emerge. In the act of creation, the ‘artist’ becomes immersed in the ‘artwork’, as a dancer becomes indistinguishable from the dance: what remains is the dance itself, ephemeral, yet at the same time, permanent and beautiful.

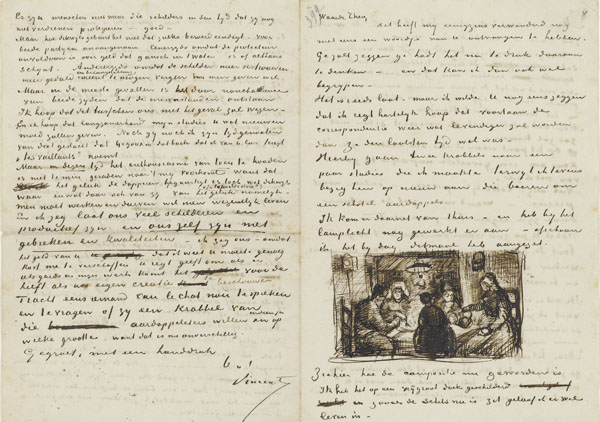

A letter from Vincent van Gogh to his brother Theo van Gogh, Nuenen, Thursday, 9 April 1885. The letter includes a sketch of his first masterpiece The Potato Eaters. Image via Wikimedia Commons

The Vision of van Gogh

.

While there had to be a degree of detachment from the painting so that it could transform, there had also to be a closeness, a caring and a deep involvement in order to really ‘get in the zone’. Looking back, after being elevated from the tedium of the task, I feel this is what the whole venture was establishing: a greater awareness of this beauty, which shifts in form, is sometimes veiled in the turning of the world, but is essentially ever-present and always possible to rediscover. If Loving Vincent is a homage to van Gogh, who held a deep reverence for this beauty, then this is where I feel it most. In July 1882, he wrote to Theo:

Though I am often in the depths of misery, there is still calmness, pure harmony and music inside me. I see paintings or drawings in the poorest cottages, in the dirtiest corners. And my mind is driven towards these things with an irresistible momentum.

So, what of this man, hidden from the world behind his paintings, whose devotion to his art inspires this gathering 125 years later? I look to his letters for insight. What did he see in those years following 1879 – the year he was moved to begin painting, at the age of 28, after four failed attempts at various careers? Or, more importantly, what did he feel? For it is the intensity of his feeling towards his subjects, and his sensitivity to their presence, I think, that nourished and stimulated his creative ambition, and is what continues to draw people close to his artwork. He expresses his distaste for ‘saleable watercolours’ – and suffers from it, relying almost always on the financial support of his brother to get by. Yet, he writes that he would rather go hungry than diminish his chances of searching for models and painting. As his letters reveal, what seems to be a radical awareness of essential beauty was also nurtured in him, which the obsessive practice of painting could only intensify.

Still from the film. Black and white sequences are used in the film to portray flashbacks of van Gogh’s life. Painting by Karol Nienartowicz

At the end of each day, I put down the brush and walk home, but consciousness does not cease to paint. The entire movement of the world sometimes seems an endless, elaborately painted masterpiece, with every moment in a slightly different configuration from the last though given no less attention and love, no less beautiful. As I walk, I find myself habitually imagining what shade of green the grass is, or if the sky should be painted in Prussian blue or cerulean – but this is quickly dropped in favour of purely observing that which exists. Each step along the pavement invites me to witness and take part in this great work of art, whether I accept the invitation or not. Each new encounter with Reality is an opportunity to be absorbed into its inherent beauty and lose myself in its continual transformation.

Is this how van Gogh felt? There is no doubt that frustration and sorrow weighed on his heart, with a longing that is familiar to anyone who has attempted to capture or harness beauty. When it hides in the fabric of the world and disguises itself as the mundane, that longing becomes greater. However, it seems this restless yearning, and the fruits of such sentiment, is what moves the spirit and wards off apathy, making van Gogh one of the most attractive and continually inspiring artists in the world.

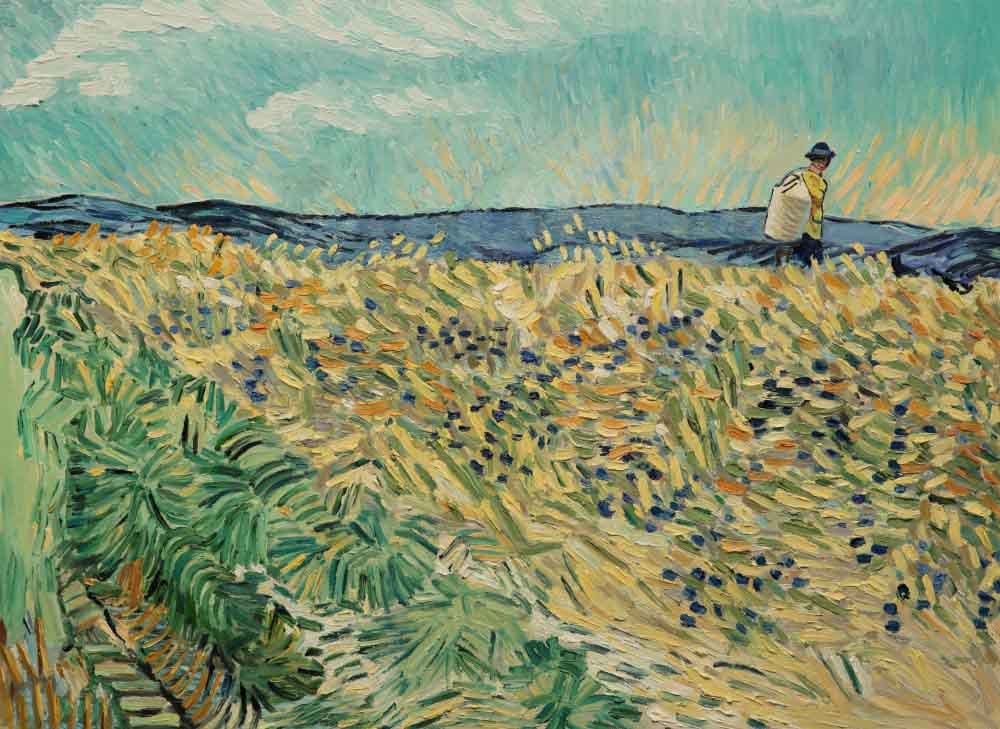

Still from the film. The countryside outside Auvers-sur-Oise, near to the spot where van Gogh is thought to have been shot. Painting by Polina Mavrikaki

The Artist’s Journey

.

After leaving the production in mid-Autumn, I avoid painting for several weeks, instead enjoying the simple act of seeing; of looking closer and closer, until beauty is revealed, no matter what form it takes. And I ask, at the same time, what is an artist? Is it someone who can be distinguished in a crowd, identified by certain behaviour? Is it someone who steps outside the circle of normality, who sits and imagines and plays with form? An eccentric, who makes sandcastles somewhere far off the beaten track, only to be destroyed by the sea? And, as I ask, I realise how much I avoid the word, due to its connotations and conjectures, its limitations of meaning. But later, reading van Gogh’s letters, the simple explanation he gives stands out to me as being unexpectedly recognisable:

… what that word implies is looking for something all the time while not ever finding it in full … As far as I’m concerned, the word means, “I am looking, I am hunting for it, I am deeply involved” (May 1882).

Maybe the artist’s journey is one without destination. Or, if a destination does exist, it exists in each step along the way, the ‘hunted’ being present in every stage of the ‘hunt’. No art form manifests this more clearly, I feel, than film, the ‘moving image’ – and perhaps particularly animation, where every image is given the attention and respect of a lover for the beloved. A film does not rush to its finish in order to pronounce itself a film. It revels in its unfolding. The artist’s spirit is present in every frame. And even if a work of art is idolised as an achievement or finished article, it remains only the appearance of a rhythm that is internal to both its creator and its beholder, for the two share the same glory. Even though the beholder may not have been involved in its creation, simply by beholding it they give it being and bring it to life. They complete the cycle. In the case of Loving Vincent, what the painter may know as a series of separate images, the audience beholds as a mesmerising, opalescent unveiling, which echoes internally and continues the dynamic process of inspiration and creation.

Still from the film. Dr Paul Gachet, van Gogh’s doctor and friend, played by Jerome Flynn [/]. Painting by Setarah Goodarzi

The outward form that art takes is only partial, but it invites the beholder to that place of direct experience and inspiration. The dissatisfaction of never being truly known must have fuelled van Gogh’s yearning and restlessness, yet it is perhaps this misfortune that retains the purity of his work and makes his work so attractive.

Can you tell what goes on within by looking at what happens without? There may be a great fire in your soul, but no one ever comes to warm himself by it, all that passers-by can see is a little smoke coming out of the chimney and they walk on (July 1880).

Whatever fire van Gogh kept hidden, the ‘little smoke’ he refers to has only increased since his death. Perhaps this smoke has culminated in Loving Vincent, a sincere tribute to the artist and his relentless, incandescent spirit. But even then, the film will keep his spirit alive, and carry the invitation on to new eyes – an invitation to fall in love with Reality.

The more deeply I contemplate any work of art, the closer I feel to the fire that fuelled its creation, to that place the artist beckons us to, though I cannot reach it through the work of art alone. I have to accept the invitation, allow myself to be moved and let it guide me to the fire inside. From the outside, the painting and repainting for months which happened on Loving Vincent may have seemed ludicrous, and the finished work may pass by like smoke. But within the endeavour, as with all acts of devotion, there is something real – a great fire, a yearning to be celebrated.

Painters and crew outside the Gdansk Studio, September 2016. The author is standing third from the right

The film Loving Vincent, directed by Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman, premiered in 2017 at the Annecy International Animated Film Festival. It has received many awards, including Best Animated Feature Film Award at the 30th European Film Awards in Berlin, and was nominated for Best Animated Feature at the 90th Academy Awards in the USA. It is now available on DVD. For a trailer of the film, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CGzKnyhYDQI

Image Sources (click to open)

Banner: Portrait of van Gogh, played by Robert Gulaczyk, painted by Anna Kluza.

Other Sources (click to open)

All quotes from The Letters of Vincent Van Gogh, edited by Ronald de Leeuw and translated into English by Arnold Pomerans (Penguin Classics, 2003).

For more information on the film in general, see http://lovingvincent.com/the-movie,3,pl.html

For a short video on the making of the film, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eOtwJL4iV8s

For a trailer of the film, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CGzKnyhYDQI

Mark Boston is a painter, animator and storyteller, currently living and working at the Chisholme Institute [/]. He enjoys all forms of art and storytelling, and seeks to work on inspiring, uplifting creative projects. His work can be explored here [/]

Email this page to a friend

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Narratives for a Unified World

Andrew Singer talks about the vision behind the literary journal Trafika Europe

Painting and the Contemplative Life

Artist and psychotherapist Benet Haughton talks about the spiritual vision that underpins his life and work

READERS’ COMMENTS

Mark Boston proves himself to be an artist of words as well as paint. What a great article and what a wonderful and unique experience to have undergone. It does read like an authentic journey of self discovery and I wish Mark Boston many more interesting travels that I hope he will share with us.

An illuminating piece of writing; thank you Mark and very good luck in your future endeavours .

Painting with words – I’d echo all that Isabel has said.

Privileged to be able to share this….thank you, Mark.

One of the most interesting and moving articles I have read for a long time. Thank you